From almost the moment Barack Obama pops out of his car, whether it’s at a town-hall meeting or a cheese-cube wingding, it’s mayhem: local officials pumping his hand, women clamoring for photos (taken by their indulgent husbands, hastily discarded pocketbooks cradled in their arms), the starstruck handing him the damnedest objects to sign (at the Illinois State Fair, one woman gives him a purple canvas sandwich cooler—“Anyone got an indelible marker?” asks an aide). The morning I connect with Obama in Effingham, Illinois, he’s got a Fox News crew in tow; the next day, at a state Democratic function in Springfield, the press vacates the ballroom where the governor is speaking—the governor must have loved that—and surrounds the senator in a loop of mikes so tight he can’t turn his face. When a local reporter discovers I’m from a publication far away, he asks if he can interview me about why I’m interested in Obama. This is what following the freshman senator has become: a small meta-chronicle of hysteria. It’s like going to view the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. All you see are the backs of people’s heads.

At almost all these stops through downstate Illinois, the senator is jacketless, RFK-style, though not tieless, which is a good thing—unlike most politicians, he has not capitulated to the tyranny of paisley. He holds people’s gazes as he speaks, and he has an unerring physical sense, knowing just how long to clasp a shoulder, linger on a hug, double-grip a hand. While Obama exudes great warmth, he doesn’t arouse the suspicion he has overrelied on sex appeal in his career, though he’s got it (six foot two, good-looking, smile like a white picket fence). People are just as apt to express their admiration around him as they are to flutter. I keep thinking of what a woman told him after the town hall meeting in Effingham: “I read your book about your father. I read the whole thing.”

The first time I have a chance alone with Obama, I ask why he thinks the world has gone gaga over him. “It’s interesting,” he says, smiling. “It is interesting.” We’re in his aide’s car, driving from a town called Palestine to another called Paris. He thinks for a moment, then suggests that perhaps the answer lies in the unique circumstances of his 2004 Senate campaign. “I sort of got a free pass, because I wasn’t subjected to a bunch of negative ads,” he says. “And nobody thought I was going to win. So I basically got into the habit of pretty much saying what I thought. And it worked for me. So I figured I might as well keep on doing it.”

Having a candid memoir already out there on the bookshelves also couldn’t have hurt. In Dreams From My Father, published nearly a decade before he was elected to the U.S. Senate, Obama freely discusses his youthful experimentation with marijuana and cocaine, and he uses the word shit—as a verb—on page four, a vivid and unambiguous choice. Did he know he’d be running for higher office when he wrote that?

“No,” he answers, then peers intently at me over the rims of his sunglasses. “But I have used the word shit before.”

Obama may be a straight shooter. But there’s one question he has a hard time answering these days, and he gets asked it a lot. At the town hall in Effingham, it takes exactly eleven minutes to come up. It’s whether he’s interested in a certain job. Candidates who are interested in it tend to attend certain dinners in Iowa, where Obama would go the following month. “I’m looking for an intelligent, highly educated man,” says a Democratic precinct committeeman from a nearby county. “Someone who hasn’t been around long enough to be labeled by the opposition in ’08—”

Obama tries to cut him off. “Uh, I think this is a setup—”

“Someone,” the committeeman plows on, “who was not from the Northeast for a change, but from, say, a large midwestern state, someone who was opposed to the war in Iraq from the beginning, someone who’s not afraid to discuss his religious experiences—”

“Um—”

“Someone who’s charismatic—”

“Uh—”

“Someone who could unite his party, unite black and white, who’d have the unwavering support of his own state. Do you know anyone like that?”

“I don’t,” said Obama, smiling but looking mildly relieved. “But if I run into the guy, I’ll let you know.”

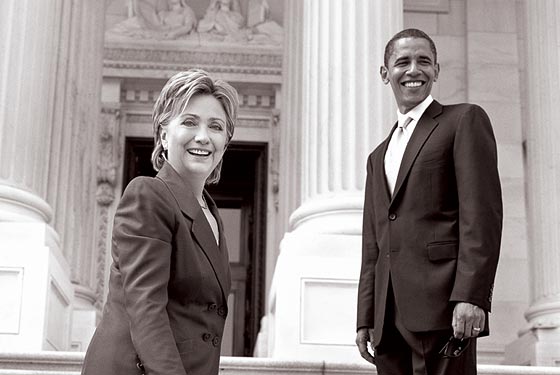

At some level, possibly the most basic one, the mania surrounding Barack Obama is a simple function of his age—or, as John F. Kennedy would have said, his vigor. At 45, he’s fifteen years younger than the average senator in the 109th Congress, and he’s thirteen years younger than Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee in 2008. (Al Gore is also 58. And John Kerry is 63.) As Simon Rosenberg, head of the New Democratic Network, says, “Obama has already established himself as the paramount leader of the next generation. There’s no one even close.” There’s something to be said for a politician who didn’t come of age wearing sideburns and listening to Simon and Garfunkel. Obama suggests there might be another way to think about politics, to speak about politics, to write about politics. It’s certainly what Crown Publishing was counting on when it awarded him with a $1.7 million, two-book contract 21 months ago. The first book, The Audacity of Hope, will be hitting bookstores in mid-October.

“To some degree—and I say this fairly explicitly in my book—we have seen the psychodrama of the baby-boom generation play out over the last 40 years,” says Obama as we’re driving through ravishing acres of corn and soy. “When you watch Clinton versus Gingrich or Gore versus Bush or Kerry versus Bush, you feel like these are fights that were taking place back in dorm rooms in the sixties. Vietnam, civil rights, the sexual revolution, the role of government—all that stuff has just been playing itself out, and I think people sort of feel like, Okay, let’s not re-litigate the sixties 40 years later.” He rattles off some of the familiar dichotomies—isolationism versus intervention, big government versus small. “These either/or formulations are wearisome,” he says. “They’re not useful. The reality outstrips the mental categories we’re operating in.”

It’s not a coincidence that Obama’s keynote address at the 2004 Democratic Convention, which turned him into a sensation, rejected either/or formulations, too. We worship an awesome God in the blue states, and we don’t like federal agents poking around in our libraries in the red states. We coach Little League in the blue states, and yes, we’ve got some gay friends in the red states …

Another of Obama’s political advantages is authenticity, that overused term which, for Obama, seems exact. “He’s real,” says Senator Jay Rockefeller, Obama’s colleague from West Virginia. “He knows who he is. And he’s someone who, I assume, would vote the way he feels.” For a party that just ran Al Gore and John Kerry—two men fundamentally estranged from themselves, terrified of saying anything that hadn’t first been printed on index cards—this trait has enormous appeal. I’ll never forget the first time I saw Obama on the Senate floor: He was telling a story to his colleagues when suddenly, quite theatrically, he struck a runner’s pose, like Jesse Owens at full tilt. It was such a strange, un-Senate-like moment to witness, totally unself-conscious and free of pomp. The other senators started laughing wildly. Later, I asked what he was doing, expecting he’d fudge an answer. Obama grinned. “Uh …” he said slowly. “We were talking about, uh, the strategy that I’d observed among some unnamed senators for, uh, ducking out of boring hearings.”

Perhaps the most captivating component of Obama’s appeal, though, is that he is only the third black candidate to be elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction. And if you’re only the third black senator in 130 years, you are bound to be the vessel for many people’s hopes. To white progressives, Obama represents the fantasy of racial reconciliation, the black RFK. To affirmative-action skeptics, he’s Horatio Alger, proof that this country affords equal opportunities to anyone who works hard enough. (Obama’s mother was a middle-class woman from Kansas; Obama’s father started out as a goatherd in Kenya.) Whatever the case, Obama’s Senate campaign certainly understood the power of white guilt. Its slogan was Yes we can—an energetic rallying cry, certainly, but also a subtle appeal to black pride and white self-respect. It dared the voters of Illinois to change the face of a lily-white institution. Which they did.

And to a younger generation of black politicians, Obama is the embodiment of progress, advancement, hope. Before July of 2004, no one had even heard of Barack Obama. He was a promising but modest figure in Illinois politics, a seven-year veteran of the state senate who’d already made one disastrous attempt for a congressional seat in 2000. But in 2004, he made a longshot bid to run for an open Senate seat. In small towns where the typical response to a person of color was to roll up the car windows, people came pouring out to hear Obama speak. He was immensely popular in both the suburbs of Chicago and the city’s whitest wards. “Twenty years ago, if I’d said there would be lawn signs with pictures of an African-American—with an African surname—all over my district on the northwest side of Chicago, people would have had me tested for drugs,” says Rahm Emanuel, head of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. “Yet there they were.”

“Barack, I think, represents a point of transition,” says Artur Davis, a 38-year-old African-American congressman from Alabama and former law-school classmate of Obama’s. “This is the first generation of African-American politicians who essentially have the same aspirations as their white compatriots. A 25-year-old black kid today who’s talented, who’s well educated, and who’s interested in politics wants to be president—and doesn’t view that as some bizarre goal. That’s what I think Barack will represent: the leading edge of the generation of African-American politicians for whom there are no glass ceilings.”

There are still plenty of black politicians who’d disagree with this, of course. At the very least, they’d point out that there’s no such thing as transcending race. It’s not an accident that black politicians who appeal broadly to whites are called “crossover” candidates—the problem’s buried right in the word. “Crossing over” suggests deserting your own kind, or being insufficiently, inauthentically black somehow (whatever on earth being sufficiently, authentically black even is). In a famous New Yorker essay, Henry Louis Gates took a long, hard look at this burdensome problem when writing about Colin Powell. He asked the general about how he’d come to be seen “as a paragon of something like racial erasure.” It was a devastating moment, I thought. I ask Obama about it during our car ride, wondering whether that perception, too, will be his lot. Clinton was who he was, I say. Kennedy was who he was. Bush is who he—

“And I feel like I’m very much who I am,” he says, cutting me off. “Do you ever get a sense that I’m not?” He looks at me pointedly, eyes over his shades, waiting for an answer.

No, I say. I don’t.

“I mean, the fact that I conjugate my verbs and, you know, speak in a typical midwestern-newscaster voice—there’s no doubt this helps ease communication between myself and white audiences,” he says. “And there’s no doubt that when I’m with a black audience, I slip into a slightly different dialect.” He turns and stretches his legs for a moment. He’s been facing me this entire car ride, though he’s in the passenger seat and I’m in the back. He turns back around and looks at me again. “But the point is,” he says, “I don’t feel the need to talk in a certain way before a white audience. And I don’t feel the need to speak a certain way in front of a black audience. There’s a level of self-consciousness about these issues the previous generation had to negotiate that I don’t feel I have to.”

This debate, in other words, has been playing itself out since the sixties. Moving beyond it may be possible. The either/or formulas are wearisome.

It’s late july, maybe three weeks before his swing through downstate Illinois, and Obama is telling an audience of D.C. interns that when he first got into politics, people were forever asking him how to pronounce his name. “People would say it all sorts of ways,” he says. “They’d call me ‘Alabama,’ or they’d call me ‘Yo mama!’ And I’d have to explain no, it’s O-bama, and my father was from Ken-ya, which is where I got my name from, and my mother is from Kansas, which is where I got my accent from.”

This story is Obama’s shorthand version of himself. The longhand, chronicled with novelistic grace in Dreams From My Father, is far more complicated, involving all the unruly algorithms of integrating a multiracial identity. “When people who don’t know me well, black or white, discover my background (and it is usually a discovery, for I ceased to advertise my mother’s race at the age of twelve or thirteen, when I began to suspect that by doing so I was ingratiating myself to whites), I see the split-second adjustments they have to make, the searching of my eyes for some telltale sign,” he writes in his introduction. “They no longer know who I am. Privately, they guess at my troubled heart, I suppose: the mixed blood, the divided soul, the ghostly image of the tragic mulatto trapped between two worlds. And if I were to explain that no, the tragedy is not mine, or at least mine alone … well, I suspect that I sound incurably naive, wedded to lost hopes, like those Communists who peddle their newspapers on the fringes of various college towns. Or worse, I sound like I’m trying to hide from myself.”

It’s extremely rare in American public life to get an intimate glimpse into the private world of an elected official. But Obama got his contract for Dreaming From My Father long before entering politics, just after he became the first black president of the 104-year-old Harvard Law Review in 1990. The result is a book that’s reflective and unsparing and totally without calculation. It also seems to provide readers with a Rosebud—an explanation for why he got into politics, and what function it serves, and how he might have developed the political instincts he has today.

Obama’s father met Obama’s mother at the University of Hawaii. Their marriage ceremony was furtive, and the marriage itself was brief; by the time Obama was 2, his father was gone, off to get a graduate degree at Harvard, and then back to his native Kenya. Barack stayed with his mother in Honolulu, then spent five years in Jakarta (his mother had remarried an Indonesian), and then went back to Hawaii again, where his white grandparents mainly looked after him until he graduated from high school. He went to Occidental College, graduated from Columbia University, and spent three years in Chicago, working as a community organizer. During that entire span, he saw his father only once, for about a month when he was 10. By the time he made his pilgrimage to Kenya in 1988, his father was dead.

In the book, you learn many things about Obama. You watch his growing awareness of black self-hatred, as when he finds an article about skin-lightening treatments in Life, or discovers a black friend wearing blue contact lenses. You also witness the reverse, a slow comprehension of white romanticism about blacks, a worldview most painfully embodied by his mother, who was visibly affected by the film Black Orpheus. “I turned away,” he wrote, “embarrassed for her.”

But mostly, what you learn from Dreams From My Father is that Obama’s whole life has been one long, painful attempt to accept contradictions and competing realities. He had to reconcile, for example, the progressive intentions of his white grandparents, who didn’t protest when their daughter married an African man, with the fear his grandmother experienced when she was accosted by a black panhandler at a bus stop. He had to reconcile the opportunity horizons of his world, where he was Harvard-bound, with the world of the menacing, despairing kids in his Chicago neighborhood. Perhaps most urgently, he had to reconcile the image of his biological father, whom Obama remembered—and whom his mother promoted—as an imposing scholar, with the actual man, who died bitter, drunk, alienated from the Kenyan Establishment, and nearly broke. “I felt,” he wrote, “as if I had woken up to find a blue sun in the yellow sky, or heard animals speaking like men.”

“I feel like I’m very much who I am,” says Obama. “Do you ever get the sense thatI’m not?”

These are seriously competing worlds. Odds are, anyone capable of holding them all is going to be a pretty good politician. And what Obama says about the process of integrating these worlds is revealing: It turns out that his first attempts to make sense of his own crazy-quilt history began when he took a role in public life, organizing poor communities in Chicago, hearing people tell stories about themselves. So he began to tell his own. “I was tentative, at first,” he wrote. “Afraid that my prior life would be too foreign for South Side sensibilities.” After all, he wasn’t describing hardships in the projects, but flying kites in Jakarta and going to dances at Punahou. Yet to his astonishment, people could still relate to him. “They’d offer a story to match or confound mine, a knot to bind our experiences together—a lost father, an adolescent brush with crime, a wandering heart, a moment of simple grace,” he wrote. “As time passed, I found that these stories, taken together, had helped me bind my world together, that they gave me the sense of place and purpose I’d been looking for.”

Participating in public life, in other words, didn’t force Obama to hide or annihilate the unresolved parts of himself, as it does with so many politicians. Just the opposite: It gave him a chance to stitch up the hanging threads of his own biography.

Obama is now contending with the hanging threads of a torn electorate and completely divided Congress. And his solution, perhaps not surprisingly, has been to write about it in The Audacity of Hope, named after a line in his convention speech, which in turn came from a church sermon that moved him to tears. “It’s not a campaign book,” says Obama as we’re still humming along in the car. “It’s me trying to describe the moment I see us being in. Like in my chapter on foreign policy—yeah, I talk about Iraq, but I’m not laying out the ten steps we need to get out of Iraq. I spend more time talking about how, historically, we got to this place.”

Whether it’s a campaign book is debatable, of course. Publishing a soul-searching, probing treatise on the state of American politics in the fall of 2006—it certainly sounds like something a prospective 2008 presidential contender would do. But it’s true that the book—or at least the introduction, posted on his Website—seems to contain many of the same elements as Dreams From My Father. It’s frank. (Although the Senate chamber is imposing, he says, it’s “not the most beautiful place in the Capitol.”) It demystifies. (He points out that when senators are talking on C-span, they’re speaking to an empty chamber.) He laments the lack of “soul-searching or introspection” on the part of his colleagues. (Who else but a memoirist would cry out for soul-searching?) And it rejects either/or formulations. (“Follow most of our foreign policy debates and one might believe that we have only two choices—belligerence or isolationism,” he writes.)

I ask how he’d reconcile the disarray of the Democrats in 2006.

“Actually, I think we do have a set of core items we agree on,” he says. “Even on Iraq, there’s uniform agreement that Bush’s policy has failed and that we need a different one.” But he agrees that without, as he puts it, “the organizing discipline” of controlling the White House, the Democrats will continue to squabble. “You’ve got at least eight Democrats running for the presidency,” he says. “It means all of them have an incentive not to unify around a strategy, but to distinguish themselves, to break out of the pack. Right? So …” He peers intently at me over his sunglasses again. “I’d say we’re gonna have some silly season goin’ on.”

We’re now in a packed room at Eastern Illinois University. A woman stands up and tosses Obama what I assume she thinks is a bit of red meat. What, she asks, does the senator think of the pervasiveness of religion in public discourse these days? Obama doesn’t take the bait.

“No one would say that Dr. King should leave his moral vision at the door before getting involved in public-policy debate,” he answers. “He says, ‘All God’s children.’ ‘Black man and white man, Jew and Gentile, Protestant and Catholic.’ He was speaking religiously. So we have to remember that not every mention of God is automatically threatening a theocracy.

“On the other hand,” he continues, “religious folks need to understand that separation of church and state isn’t there just to protect the state from religion, but religion from the state.” He points out that, historically speaking, the most ardent American supporters of the separation between church and state were Evangelicals—and Jefferson and Franklin. “Who were Deists, by the way,” he adds, “but challenged all kinds of aspects of Christianity. They didn’t even necessarily believe in the divinity of Christ, which is not something that gets talked about a lot.”

Back in the car, he elaborates on the kinds of themes he tries to communicate to his constituents. “To me, the issue is not are you centrist or are you liberal,” he says. “The issue to me is, Is what you’re proposing going to work? Can you build a working coalition to make the lives of people better? And if it can work, you should support it whether it’s centrist, conservative, or liberal.”

As a rule, Obama tends to avoid divisive rhetoric, and he works hard to reconcile warring political points of view—an instinct, if you look carefully at his memoir, that he clearly learned in his youth. As a teenager, for example, he argued with a black friend that maybe white women refused to date him not because they were racists, but because “they just want someone who looks like their daddy, or their brother, or whatever, and we ain’t it.”

And so this impulse to reconcile now shows up in politics. In town-hall meetings, when those who opposed the war get shrill, Obama makes a point of noting that while he, too, opposed the war, he’s “not one of those people who cynically believes Bush went in only for the oil.” When I ask about Lieberman’s recent vilification of the left, Obama seems equally vexed: “His most recent comments tying the bomb threat in Great Britain to Iraq was a pretty crude political play.” Obama’s first year in office, he voted for cloture on the nomination of John Roberts to the Supreme Court (though not for the nomination itself), earning dozens of angry posts on Daily Kos, a hugely well-trafficked liberal blog. Obama responded with a polite but stern four-page note.

“One good test as to whether folks are doing interesting work is, Can they surprise me?” he tells me. “And increasingly, when I read Daily Kos, it doesn’t surprise me. It’s all just exactly what I would expect.”

Which is not to say that Obama doesn’t have very strong partisan convictions. “There are times I think we’re not ambitious enough,” Obama says. “I remember back in 2004, one of the candidates had made a proposal about universal health care, and some DLC-type commentator said, ‘We can’t propose this kind of big-government costly program, because it’ll send a signal we’re tax-and-spend liberals.’ But that’s not a good reason to not do something. You don’t give up on the goal of universal health care because you don’t want to be tagged as a liberal. People need universal health care.”

According to Congressional Quarterly, Obama voted with his party 97 percent of the time in 2005—the same as John Kerry and three others—with only eight senators voting consistently more Democratic than he did. (As a point of contrast, John McCain voted with his party only 84 percent of the time.) It’s hard not to call that record liberal, as much as Obama dislikes labels. When Obama was still in the Illinois state senate, his contributions were certainly viewed as liberal—sponsoring the Earned Income Tax Credit, requiring that confessions for capital crimes be videotaped—though he was also known as a man who worked skillfully across the aisle.

“Look, Barack Obama’s a likable fellow and he’s smart,” says Lindsey Graham, an independent-minded Republican senator from South Carolina who’s a close ally of John McCain. “But to be a major player in the Senate with a polarized nation, you’re going to have to demonstrate the ability to take criticism from your friends. Challenging your political enemies is easy. Taking on your friends is hard.”

Earlier this year, McCain himself sent Obama a scathing note, accusing him of being far too partisan on the subject of Senate ethics reform, a matter they’d jointly undertaken. “I understand how important the opportunity to lead your party’s effort to exploit this issue must seem to a freshman senator,” his note said, “and I hold no hard feelings over your earlier disingenuousness.”

And yet there’s still something in Obama that’s slightly reminiscent of McCain. Both speak bluntly about what they believe, and seem all the more trustworthy for it. Both are ethics-reform nuts, showing they’re not especially attached to how the Senate does business. And the identities of both men were forged outside the Senate rather than inside, meaning politics isn’t the be-all and end-all of their lives. Aren’t these the kinds of politicians the electorate craves?

“If Barack disagrees with you or thinks you haven’t done something appropriate,” says Tom Coburn, a Republican senator from Oklahoma, “he’s the kind of guy who’ll talk to you about it. He’ll come up and reconcile: ‘I don’t think you were truthful about my bill.’ I’ve seen him do that. On the Senate floor.”

Obama’s friendship with Coburn, one of the most conservative Republicans in the Senate, may be the best evidence of Obama’s native ecumenism. The two met at freshman orientation, and their wives hit it off; now they have dinners together and are co-sponsoring bills, including one that creates a public database of government spending. (It sailed through both House and Senate two weeks ago.)

“What Washington does,” Coburn says, “is cause everybody to concentrate on where they disagree as opposed to where they agree. But leadership changes that. And Barack’s got the capability, I believe—and the pizzazz and the charisma—to be a leader of America, not a leader of Democrats.”

If I didn’t know any better, I’d say he was calling Obama a uniter, not a divider.

People often like to ask whether the country is ready for a black president. “The test is not a Barack test,” says Jesse Jackson, who ran for president in 1984 and 1988. “It’s America’s test. Phenomenal blacks are wonderful, but they ain’t new. Do you know how qualified Paul Robeson was? All-American, Phi Beta Kappa, Othello?”

Al Sharpton, who ran for president in 2004, still doesn’t see how race can’t ultimately insinuate itself into the core of a black person’s political identity. “As long as Barack Obama’s talking hope, as long as he’s talking the dream … as long as he’s not an Al Sharpton, he’s fine,” the Reverend says. “But in a race situation, when Katrina happens, or affirmative action comes up, he’s going to be asked by the media to talk about that. That’s what he’s got to be careful about.”

Back when he ran for Congress in 2000, hoping to unseat the former Black Panther Bobby Rush, Obama ran up against some hard-core identity politics and activism, when Rush implied Obama wasn’t “black enough.” Today, in Congress, Obama is acutely aware of the debt he owes to black activists of a previous generation, including men like Rush. Yet there are plenty of activists in Obama’s own generation who still consider Obama’s election an anomaly—or, at the very least, something less than “a point of transition,” as Artur Davis says. “Forty years ago, after the election of Ed Brooke”—the first African-American sent to the Senate since Reconstruction—“people said we didn’t need the protest movement anymore,” says Sharpton. “And then there wasn’t another black senator for 26 years. Every generation has this debate. Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois had it 110 years ago.”

Obama has thought about being president. He’s never been coy about that. I bring up Henry Louis Gates’s essay about Colin Powell again. In it, Gates drew a very sharp distinction: Jesse Jackson wanted to be the first black president. Powell, were he ever to run, wanted to be the first president who happened to be black.

“I don’t think that those two are necessarily opposing,” says Obama. “I don’t want people to pretend I’m not black or that it’s somehow not relevant. But ultimately,” he says, “I’d want to be a really great president, you know? And then I’d worry about all the other stuff. Because there are a lot of mediocre or poor presidents.”

It’s a view, once again, that quietly reconciles—not unlike how Kennedy viewed his Catholicism. Kennedy wasn’t a Catholic president or a president who happened to be Catholic; he was neither, and both. Obama, similarly, invokes the possibility that racial politics isn’t a zero-sum game, where someone must choose between activism or self-imposed color blindness. He invokes the possibility that black Americans in public life might not have to live with what Gates calls “the burden of representation”—the ludicrous, impossible notion that they must represent their race every time they vote, or act, or speak.

At some point in the car, I finally ask Obama if he’s ruled out running for president in 2008—dumbly thinking, as so many journalists dumbly do, that maybe I’d have more luck getting to the bottom of this question by asking it in the negative. “Well, I mean, you know,” he says. “People have asked me if I’m running in ’08, and I’ve said no. And if I change my mind, I’ll let you guys know.”

So he has kept the door ajar. He is saying he could change his mind.

Does he have a fantasy candidate for the Democrats in ’08?

“No.”

Obama could always be vice-president. In Washington, Democrats love to kick that idea around, though most people seem to agree he’d have to be paired off with someone more experienced, and that it couldn’t be Hillary. “Look,” says strategist Joe Trippi, who’s worked on the campaigns of many black candidates. “If Obama won the presidential nomination, he couldn’t pick a Latino to be his vice-president, right? So if Hillary wins the nomination …” He doesn’t finish the sentence. “I’m trying to deal with the political reality here.” But he does think Obama would make a compelling running-mate to someone like Senator Evan Bayh of Indiana (“Missouri could come into play”) or Governor Mark Warner of Virginia. “If he were paired with someone from the Midwest or the South,” says Trippi, “it’d be an electrifying ticket.” (Though if Al Gore ran in 2008 and chose Obama, he’d be the first presidential candidate in history to have selected both a Jew and a black man as his running mates—not a bad epitaph.)

“Barack may be the first post-ideological candidate,” says Rahm Emanuel.

Post-ideological how?

“Name me a state he can’t go to,” he says. “John McCain can go to New York all he wants, but it ain’t gonna happen. New York ain’t gonna vote for him. Or George Allen, for that matter”—a Republican senator from Virginia, also a presidential hopeful—“or Mitt Romney.” (The governor of Massachusetts.) “But I think Barack could be a player in all 50 states, if he wants to. Or 40. There are states we have lost, historically, that he’d be a major player in.”

“I don’t want people to pretend I’m not black,” says Obama.

Perhaps he’s right. But we have seen this before. Bill Clinton also spoke of a Third Way, won red states, and appealed to all races and creeds. (In fact, didn’t Toni Morrison call him the first black president?) His speech at the official opening of his library even echoed Obama’s keynote address, in the part where the president called himself “a little bit of red and a little bit of blue.”

It’s possible, in other words, that Obama isn’t a harbinger of anything to come, but is a singular personality, much like Bill Clinton. As Emanuel says, “People are interested in Barack as a person. Nobody gives a shit about me as a person.”

And if that’s the case, Obama can afford to wait. Because let’s face it: Obama is really green. People love to compare him to JFK, but Kennedy had at least served a full Senate term before announcing his candidacy, plus six years in the House. We don’t know whether Obama has a lot of policy imagination, nor is it clear what his vision of a post-baby-boomer agenda looks like.

Obama-in-’08 enthusiasts still think it’s worth the risk. Wait longer, and you become an insider. You start speaking like a cyborg. You become burdened by your own voting record. You lose touch.

But is that what being an insider is? A function of time? A matter of place?

Read Dreams From My Father, and it’s pretty clear Obama has always been an outsider. As a kid, he wound up in untold family scrapbooks of strangers, because his white grandfather would tell staring tourists that he was the great-grandson of King Kamehameha, the first monarch of Hawaii. In college, he envied the “authenticity” of the black kids who grew up in big families in urban settings, knowing he grew up on Waikiki beach. And when he finally traveled to Kenya, a trip he believed would be his own version of Roots, he realized he was both a native and a stranger. Yes, he could “experience the freedom that comes from not being watched, the freedom of believing that your hair grows as it’s supposed to grow and your rump sways the way a rump is supposed to sway.” But at the same time, he saw how disenfranchised his own Kenyan relations felt. One asked him for money. Another, his half-brother, listened to him with only half a heart when Obama tried to give him career advice. “He must have been wondering,” Obama wrote, “why my rules somehow applied to him.”

Read Obama, in other words, and you realize outsiderness isn’t so much a phenomenon of geography as of character, sensibility, state of mind.

At a quick stop outside Palestine, a woman grabs Obama by both arms. “We need you to run for president. You must. You must. Are you running?”

Obama demurs. “I can’t make news.”

“Obama for president,” her husband repeats. “That’s the answer.”

He thanks them both, moves on—and then another couple tells him the same thing about six seconds later.

So much hope and so much fuss. All over a man whose father was from Kenya and whose mother might have been a distant relation of Jefferson Davis. Whose meals in Indonesia were served, for a time, by a male servant who sometimes liked to wear a dress. Whose first and last names inconveniently rhyme with “Iraq Osama.” And whose middle name, taken from his Muslim grandfather, is, of all things, Hussein.

Where else but here, though, right?