Spend enough time on the campaign trail and you really do wonder how presidential candidates manage to stay sane. Twenty-four hours into John McCain’s announcement tour, the venues have already started to run together in a blur of streamers, hot-dog stands, and high-school bands playing “This Land Is Your Land” in the same trumpet squall. The senator has received all manner of pointless tchotchkes and doodads. (“Do you know how many baseball caps a candidate gets per day?” asks Michael Deaver, the old Reagan hand.) He has said I’m not the youngest candidate, but I am the most experienced at least six times. Twice, he’s had to smile—and act as if he found it so original—when his supporters gave him valedictory send-offs to the tune of “Barbara Ann,” a nod to the “Bomb Iran” wisecrack he made some weeks back. And somewhere between New Hampshire and South Carolina, the Arizona senator has gotten into a tense quarrel with the press corps, who cannot believe that a man who bills himself as a straight talker refused, just the day before, to answer their questions about Alberto Gonzales until they’d already filed their stories—at which point he told Larry King he thought the attorney general should resign.

“Well, the fact is, I wanted yesterday’s stories to be about the announcement of our campaign,” says McCain when confronted about the discrepancy at a press conference. “If your tender feelings are bruised, then I apologize.”

Given America’s unconcern with the Geneva Conventions and McCain’s own harrowing history as a prisoner of war, perhaps Mark McKinnon, an adviser to the senator, could find a more delicate metaphor when he compares the process of running for president to torture. But he’s certainly onto something. “Think about it,” he says. “There’s sleep deprivation. You don’t know when your next meal is. You have the same sensory stimuli over and over until it drives you crazy. People are asking you questions, trying to trap you. And you’re watched all the time. It’s designed to break you down.”

It’s also the last remaining freak show in the United States, which is hardly to everyone’s taste. Gary Bauer, a Republican Evangelical who made a quixotic primary bid in 2000, says he had a hard enough time coping with the “butter lady” at the Iowa State Fair. “Her claim to fame was that she always brought sculptures made completely out of butter,” he says. “They were displayed in a refrigerated case. And … well, you’re going to think I’m making this up, but guess what the sculpture was that year?”

A bust of his head?

“No,” he says. “That I probably could have dealt with. No, no. It was the famous painting of the Lord’s Supper. The Lord’s Supper! It was humongous. The length of this room”—he points to the opposite wall of his Arlington, Virginia, office, maybe twelve feet away—“and pretty darn deep. I’m serious. The entire scene of Christ and all the disciples. And I don’t even know how you react to that.”

When Bob Dole ran for president in 1996, he says, the journalists who followed him knew his stump speech so well they’d recite it on the plane. After two days of following McCain, I realize I could probably do the same. Already I can reel off his jokes, his favorite rhetorical questions, and, of course, his tagline: That’s not good enough for America. And when I’m president, it won’t be good enough for me!

Which raises a crucial question: If I’m already sick of McCain, how does McCain feel?

“I get tired of some of it,” he says, as we roll along on the Straight Talk Express. “But there’ll always be new issues, new aspects of whatever the issues are. They’re always changing, when you think about it.”

And this is a fine answer, a perfectly politic answer. Any man with serious presidential ambitions cannot say how anesthetizing, peculiar, or extravagantly nuts he finds certain aspects of the modern American presidential campaign. But his response was disappointing somehow, and it’s only later that I realized why: It was rote. Even this question—Golly, how can you stand it?—John McCain had probably been asked a dozen times before.

Authenticity has become a dominant meme of this campaign season. From the very beginning of the 2008 cycle, both parties—or large segments of them, anyway—seemed eager to find a presidential candidate who didn’t suffer from a phoniness problem. Admittedly, Democrats experienced this desire more urgently than Republicans, because the men their party ran in the past two elections looked as if they’d been specifically selected for their extra coatings of polyurethane. With Al Gore, voters at least sensed that there was another man rattling around in there somewhere—a funnier man, one who cared deeply about the environment and had a gift for explaining why we should, too—and An Inconvenient Truth showed this to be true. With John Kerry, the problem ran deeper: To this day, it’s not clear what he’s passionate about. (He was more like the random books one finds on the shelf at a summer share—palatable, but loved by no one.)

After Kerry’s defeat, many Democrats thought it a sensible goal to find a nominee in 2008 who wasn’t stage-managed and poll-tested within an inch of his or her life. But 2008 is supposed to be Hillary’s year. And, as millions discovered this March, she looks entirely plausible in a parody of an Apple campaign based on 1984.

Complicating matters further this cycle is the advent of YouTube. When television came along, politics may have become a scripted teleplay. But with YouTube, it’s a reality show, where the audience gets to see not only the final, blow-dried product, but the blow-drying itself (John Edwards, predictably, is the poster boy for this effect), as it happens in real time. This is a very profound change. YouTube has the power to expose the lies that make political theater possible. It has the power to show how backstage versions of our politicians can, at times, not just be unlovely but directly contradict the image of the person we see on television. If this new world of amateur surveillance makes candidates paranoid and self-censoring, their speech really could be like something out of 1984—measured, state-approved, one size fits all.

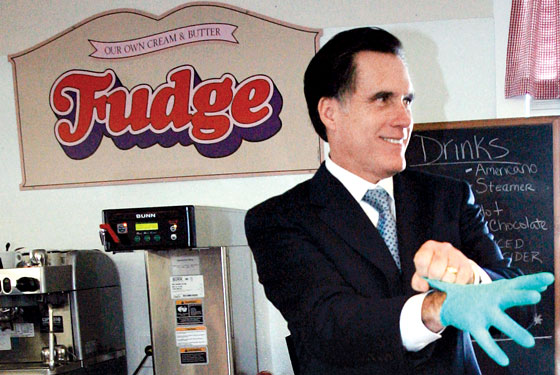

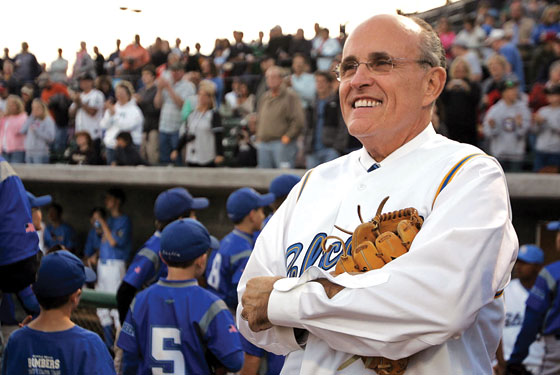

This year, each primary, in a sense, is a contest between those who are fake and those who are not. One of the main sources of Barack Obama’s appeal is that he’s not Hillary, as the Apple-Orwell-1984 mash-up so pitilessly pointed out. Rather, he seems a fellow with a low zombie quotient—someone who wrote a moving and introspective memoir, someone who sang the Muslim call to prayer for the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof and called it “one of the prettiest sounds on Earth at sunset.” (As Kristof wrote, this isn’t exactly going to endear the man to voters in Alabama.) On the Republican side, there’s Mitt Romney at one extreme (high zombie quotient), Rudy Giuliani at the other (still hewing to the pro-choice line, still talking with the cheerful opinionatedness of a New York City mayor), and McCain as a kind of phoniness parable, a cautionary example of what happens when a leopard tries to change its spots. Back in early 2000, McCain lived up to the overused moniker of maverick, saying whatever popped into his head, including his unmistakable conviction that Jerry Falwell and his brethren were “agents of intolerance.” Yet at the beginning of this cycle, when it was clear he stood a real chance of winning, the shorter odds corrupted him, prompting him to give the commencement speech at Falwell’s Liberty University and make a few other cynical overtures to the conservative base. It cost him dearly among independents, according to polls. Now, with some modifications, he’s back to his old self, criticizing Bush and cursing those who stand in his way. (Recently, when Senator John Cornyn gave him grief about his immigration bill, he succinctly retorted, “Fuck you.”)

“You’d be amazed at how many senators are shy people. They hate running for office. They just force themselves.”

—Gary Hart

It’s easy to blame the system, the endless fund-raising and staged events and media scrutiny that borders on the proctological, for the current epidemic of phoniness. If only, the argument goes, a system could be arranged where politicians’ real selves and real ideas were always and everywhere on display, we would have the politics we deserve. But it’s also possible that phoniness, at least in certain forms, serves an important purpose. It may even be a desirable quality in politics. It’s certainly something we consistently choose, consciously or not.

In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, a seminal social-science book that’s a de facto primer on effective political communication, sociologist Erving Goffman gives a great deal of thought to how people show themselves to the world, viewing all forms of human interaction as a kind of managed drama. “When the individual has no belief in his own act and no ultimate concern with the beliefs of his audience,” he writes, “we may call him cynical, reserving the term ‘sincere’ for the individuals who believe in the impression fostered by their own performance.” Anyone who’s listened to Mitt Romney for more than ten seconds can surely grasp this distinction.

But there’s a whole spectrum of behaviors, Goffman notes, between these two extremes. Sometimes sincere actors delude their audiences because their audiences want to be lied to—body-conscious women in clothing stores, patients taking placebos. Sometimes people grow into roles that were once unnatural. Sometimes they grow disenchanted with roles they once inhabited so well. And sometimes actors believe in the sincerity of their performance and its fraudulence all at once.

But whatever the circumstances, writes Goffman, part of playing a role well is learning how to suppress spontaneous reactions. In political terms, this is part of what’s known as message discipline. More broadly speaking, Goffman’s point is that it’s important, in any performance, to maintain the line between audience and actor. As Bob Kerrey, the former Nebraska governor and senator who ran in the Democratic primary in 1992, points out, “One of the things I discovered when I became governor of Nebraska is, ‘There’s a role I gotta play here.’ We didn’t have to put on robes and all that, obviously. But I had to learn how to be this person.”

But who can best learn to be the president? Seeking the forces that are driving the political process leading up to the election in 2008, I wanted to look at this process from the inside, from the point of view of those who’ve undergone it in the past or are undergoing it now. What does it do to a person to devote all his or her energies to something that can seem so ludicrous? Do you have to be a mannequin to survive a pageant? Does the process turn you into one? Exactly whom do you have to be?

McCain is sitting in the back of the Straight Talk Express, having a lively dispute with a reporter about what, precisely, Harry Reid, the majority leader of the Senate, meant when he said the war was lost.

“He meant it couldn’t be won militarily,” the reporter says.

“Well, that’s the way wars are usually decided,” McCain replies, giving her a look of deadpan exasperation. “Generally speaking.” Then, gamely: “Though sometimes they are decided by a jousting match! Between two selectees! Of the opposing armies!”

For all of McCain’s attempts to recast himself as a mainstream character, he remains, at bottom, an insurgent, someone whose instincts are more rebellious than political. One senses it has something to do with the five and a half years he spent in a POW camp in Vietnam—after enduring the things he did, what does he care if he pisses off people or speaks his mind? (As the late Michael Kelly was fond of noting, veterans often make interesting political candidates for this reason.) But whatever the provenance of McCain’s candor, it’s been in full flower recently. In addition to the recent “fuck you” incident, he told bloggers he had little patience with Mitt Romney’s wifty positions on immigration: “Maybe he can get out his small varmint gun and drive those Guatemalans off his yard.” He also piquantly highlighted Obama’s failure, in a press release, to spell a word a president ought to know: “By the way, Senator Obama, it’s ‘flak’ jacket, not a ‘flack’ jacket.”

“I would much rather have a phony, competent person in the White House than an incompetent, authentic person. I’m not sure the two aren’t correlated: The greater competence you’ve got, the more you’ve got to be phony in order to get the job done.”

—Bob Kerrey

In the Straight Talk Express, McCain has found the vehicle, both literally and figuratively, that plays to his strengths. In the protected confines of a bus, he’s free to schmooze, argue, uncork in his loony-tunes way. The problem is that this discursive quality doesn’t translate well into the rigid formatting of televised debate—he looks tense, rattling through his talking points like an auctioneer—and his irreverence is positively jarring out of context. Think of the angry reaction to his “Bomb Iran” moment, or the moment on The Daily Show when he awkwardly joked he’d picked up an improvised explosive device at the Baghdad market. It’s worth pointing out that McCain sang “Bomb Iran” to a small VFW hall of veterans like himself (in response to a very specific question: “When do we send ’em an airmail package to Tehran?”), and two days after his appearance on The Daily Show, he twice referred to roadblocks to immigration reform as “IEDs,” rather than “obstacles.” Unless you follow McCain on the campaign trail, you’d never know how war metaphors suffuse his speech.

Zephyr Teachout, the Internet philosopher and director of online organizing for Howard Dean’s primary campaign in 2004, writes in an e-mail that she sees two possible directions political discourse could take in a YouTube age:

The first future, the gloomy one, is one in which constant surveillance turns our politicians into plastic people, and turns creative, thoughtful people—people who are willing to think out loud—off from pursuing public office. The second future is the one in which the current plasticness becomes so unsustainable that it goes the other way—we become much more comfortable with awkward phrasing.

Unfortunately, she concludes, the gloomy future strikes her as the more likely one. It has something to do with the way the media—writ large, new and old—teaches us all to be strategists, not citizens, and to think poorly of someone as a strategist, not a person, for saying something stupid.

The irony in this new, strange age of amateur surveillance is that the old media may also come to the rescue. The press at least mediates (it’s not called the media for nothing), providing context for remarks and maintaining confidentiality if certain things were said off the record or in jest. It’s yet another reason McCain may like the Straight Talk Express so much. On the bus, I ask him if YouTube is going to make him more neurotic about what he says in small settings.

“I can’t be any different,” he says. “This is a tough slog”—another war metaphor—“everybody knows that. You gotta be who you are. But will I make some mistakes? Absolutely. Stand by.”

Paul Begala, one of the senior advisers to Bill Clinton in 1992, makes a useful observation about his former boss, and oddly enough, he invokes Goffman to do it. “Erving Goffman used to make the distinction between front stage and backstage personas,” he says. The terms are self-explanatory—front stage is who the audience sees, and backstage is who intimates see, the person we suppress while performing. “Bill Clinton has the least distance between his front stage and his backstage personas out of anyone I know.”

Deaver says the same thing about Ronald Reagan. It can’t be an accident that both of these men were the two most popular presidents of the late-twentieth century. Nor can it be an accident that men with more private selves—Gore, Kerry, Dole—had a harder time when they stepped into the limelight. I ask Kerry’s former campaign adviser Mary Beth Cahill when the senator seemed most like himself on the campaign trail, and her answer is startling: “On the plane, I think, when he’d be in the front cabin, playing his guitar by himself.” He was most like himself, in other words, when he was alone.

Yet here’s a wrinkle: McCain is also the same both front stage and back. Many mavericks are. Bob Kerrey. Chuck Hagel. (Also both Vietnam vets, it should be noted.) So why do they seem like longer shots for president? What makes them different? Why don’t they have the same success?

‘They wouldn’t let me be funny!” Dole is saying, then catches himself. “Well, they.” He leans back. He’s sitting in one of the stateliest rooms in his suite at Alston & Bird, yet looking uncharacteristically informal: navy slacks and no jacket, legs stretched way out, as if lounging on a deck chair. “They kind of said, ‘We don’t want a comedian. This is serious business.’”

Bob Dole is not a man whose front-stage and backstage personas were the same, at least while he was in politics. Backstage, Dole was a total cut-up; front stage, he was stiff, gruff—and 1996 was a real improvement over 1988, when he made a credible primary run. (Then, his front-stage persona was perilously close to Darth Vader’s, minus the wheezing.) So one of the first questions I ask when I visit him at his law office in Washington is, Why wasn’t he funny on the stump? And his answer is, They wouldn’t let me.

“I don’t think anyone asked him not to be funny,” explains William Lacy, a former Dole adviser. “We just saw the importance of more message discipline, of having a message every day to get across, and that’s something he struggled with.” The trouble with humor, explains Lacy, is that it’s discursive—once Dole got rolling, there was no stopping him. That worked just fine when he first came of age politically, stopping in people’s farmhouses and putting 50,000 miles on his car, but television changed all that. He never got used to it. Bob Dole the person was so alienated from Bob Dole the brand that he referred to it—referred to himself—in the third person.

“I had trouble staying on message, yeah, that was one of my problems,” says Dole. “I’d wander into some forest somewhere and finally get back to where I was supposed to be. But after you give the same speech over and over, you don’t have the enthusiasm! It’s not like, Boy, I’ve got a great speech here—I’m going to go out and wow the crowd!”

Indeed, that tends to be something natural performers, like Clinton and Reagan, are far better at pulling off. To them, it doesn’t feel like dreary repetition. The transaction with the crowd, not the words themselves, gives them energy.

I ask Dole about the pageantry and props that come with the territory. “Yeah, I found it hard to do a lot of those things,” he says. “All the stupid things you wear—the jackets are okay, but the aprons and big tall chef’s caps while you’re serving chop suey or whatever it is. You look like a monkey.”

He thinks some more, then remembers something. “A parade in Illinois—Wheaton, Illinois—Bob Woodward’s hometown, think his father was a judge there.” Dole is filled with such asides. “It wasn’t that I was wearing anything. But I remember the incident well, because this lady came rushing out with her baby and handed me her baby. But I don’t use my right arm. And my left is not too strong. So, uh, I’m just scared to death.”

He never says what happened to the child. He simply says what happened next: “Somebody next to me got under me right away and caught the baby.”

He tells this story so matter-of-factly it’s easy to miss the punch line—and its implications. As a wounded World War II veteran, Dole went an entire presidential campaign giving people the impression he was afraid of small kids.

“You know, people want you to kiss the babies, hold the babies,” says Dole. “It’s fine. But, uh, I remember that very well. I was scared to death.”

Not that Dole ever had much of a chance. The economy was thriving; Clinton’s popularity was high. He says it took a toll on him sometimes, having to pretend the election was winnable. “I said at my convention that I’m the most optimistic man in America,” he says. “But privately … you know. When you kinda have that cloud hangin’ over, it doesn’t look good.”

Dole had to exit political life in order to bring his backstage and front-stage personas into alignment. Today, he’s everything his advisers wished he were then: open about his disability, sunny, funny. Like Gore, he just needed a different kind of media experience—appearances on Letterman, commercials about Viagra and Pepsi—to get him there.

“I can remember the Secret Service dropping me off on Election Night,” he concludes. “You know—good-bye!” He gives a little wave. “And then you say, ‘What do I do tomorrow?’” He smiles, and I notice that his right arm, which he’d always taken such enormous care to hike up and close around a pen, now rests, relaxed, at his right side. The pen’s still there. But the tension’s gone. “But somebody has to win,” he says. “And somebody has to lose.”

“This Lady came rushing out and handed me her baby. But I don’t use my right arm. And my left is not too strong. So, uh, I’m just scared to death.” Dole never says what happened to the child. He simply says what happened next. “Somebody next to me got under me right away and caught the baby.”

Years ago, while they were serving together in the Senate, Bob Kerrey and John McCain both worked on the POW/MIA committee. It was an extremely sensitive assignment for both of them, but even more so for McCain, who’d been a prisoner of war. Over the course of the year, Kerrey recalls, McCain got so incensed at a fellow senator—an Iowa farmer named Chuck Grassley—he was convinced McCain was going to bodily harm him during a meeting with colleagues and staff. “I knew he wasn’t going to stand up and hit Grassley,” says Kerrey, “because when John came out of the plane in Vietnam, his arms were ripped out of his sockets, and they rebroke them several times when he was in prison. But I am thinking, He’s going to head-butt Grassley and drive the cartilage in his nose into his brain. I’m going to watch a colleague kill a colleague. That’ll give me something to remember on this day.”

McCain didn’t head-butt his colleague. Instead, he kept repeating, “You know what your problem is, Senator? You don’t listen,” until the two men were nose-to-nose. Then McCain revised his opinion: “But that’s not your problem. Your problem is, you’re a fucking jerk.”

“John hates when I tell this story,” says Kerrey. “But I like that anger. When he got mad, I liked that he became Shiva.” Shiva is the Hindu god of destruction, the destroyer of worlds. “I have a very high regard for John McCain,” he adds. “But in a campaign, that temperament becomes an issue.”

Straight talk, in other words, may be hazardous to a political career, as welcome as it may be.

Hello? Hi, Brian. When do you want to come over? I’ve got a meeting from 3:30 to 4:30; otherwise I’m clear …

I am sitting in Michael Dukakis’s office at Northeastern University, where he is, ever the retail politician, answering his own phone. He finishes, looks up, and apologizes. “I loved the primary,” he begins, recalling the golden days of 1988, before his campaign ended in an electoral rout. “Because I’m a guy who loves campaigning on the ground. I wouldn’t have been made dogcatcher if I weren’t a grass-roots, precinct-based sort of guy. But once you’re the nominee … then you get security. I never had it as governor”—of Massachusetts, his day job at the time—“so I was the last candidate on either side to say yes to the Secret Service. And if it hadn’t been for 15,000 absolutely insane Greeks in Astoria that almost trampled us to death with their enthusiasm … ” Kitty, his wife, remembers it well. They were shaking the car with such vigor she thought they were going to turn it over. “Once you say yes to the Secret Service, a kind of walling off takes place,” he says. “And I found it difficult.”

During the 1988 presidential campaign, Dukakis came across as cold, academic, and overly righteous. It is shocking how different he comes across in a small setting. In his office, his style is warm and unfussy; he’s a careful listener and questioner. Even the famous Velcro eyebrows make sense. They give his eyes depth.

“Now, are there ways to break through that?” he asks. “Yeah. I think the Clinton-Gore bus trips were an inspired idea. I’m sorry we didn’t have those. Because on that level, you see things, people tell you about things. Drove the Secret Service crazy, but Clinton and Gore got the kind of spontaneity—the kind of learning—you don’t get in canned events, where you’re up in the plane, down, up in the plane, down.”

Like Dole, Dukakis didn’t have a flair for the up in the plane, down. “Part of the problem here is that most of us—I don’t care whether it’s Dukakis, Gore, Hart, whoever—most of us started in politics in living rooms and backyards and Legion halls,” Dukakis concludes. He’s talking about himself in the third person, just like Dole, as if to say, that politician-fellow named Mike Dukakis is a different man entirely. “And generally speaking, if I may say so, we’re very good at it. But see, how do ya translate that? I can’t deliver a speech off prepared text for love nor money. If I had a nickel for everybody who’s come up to me since 1988 and said, ‘You’re nothing like the guy we were watching on television … ’ I say to them, well, that was eight seconds. Clinton—Clinton can do it in eight seconds. Reagan. I gotta spend an hour with people.”

Anything short of that had the potential to result in disaster. During the second presidential debate, CNN’s Bernard Shaw famously asked Dukakis whether the death penalty would be appropriate if a stranger raped and killed his wife. He gave a characteristically unemotional answer: No, I don’t, Bernard. And I think you know that I’ve opposed the death penalty during all of my life … People say it cost him the election. Kitty herself was stunned. (“Afterwards, I turned to him in the car and said, ‘What were you thinking?’ ”she says.)

“Look, when you’re opposed to the death penalty, you’re asked that question a thousand times,” Dukakis says today. “Unfortunately, I answered it as if I’d been asked it a thousand times. Folks expected more, I guess.”

A couple weeks ago, Warren Beatty called me up and said, ‘Let me ask you something: Do you think you have to be crazy to run for president?’ ”

This is Gary Hart, the Democratic senator who swept half the primaries in 1984 before flaming out.

“And I said, ‘What do you mean? Not crazy crazy, right?’ ” he says. “And he said, ‘Well, not conventionally normal.’ And I began to think about that. Because I … I don’t think I’m crazy. But I think what he was getting at was some combination of compulsion, drivenness, neuroses—who knows?”

What does he mean, who knows? He ran for president. What are the excesses of a presidential personality?

“Well, high energy. And a bit of … let’s see. Whatever the sane side of messianic is. A sense that you can see farther ahead than most people. I’ve always felt that that was my strength, that I could see farther ahead than most people.”

Whatever the sane side of messianic is. Because of its fractured grammar, this is possibly the loveliest—and truest—iteration of a campaign cliché, that a candidate for president must have a vision to convey. “And an ability to relate,” he adds. “And I’ll tell you how this is strange. The tagline for me throughout ’83 was ‘cool and aloof.’ But the only reason ‘cool and aloof’ came about is because I was shy—instead of working a room, I’d get my back against the wall. But I’d get into a conversation, and within twenty minutes, I had the whole room around me.”

How does a shy person run for president?

He gives a mild shrug. “There’s a stereotypical belief that to be a politician, you have to need acclaim and gratification and acceptance,” he says. “I never did. You would be amazed at the number of senators who are shy people. They hate running for office. They just force themselves. You’ll do whatever it takes, if you have that sense of seeing over the horizon.”

Hart is surely right. Given the right circumstances, a shy person can become president. But if history is any guide, it helps to be the kind of person who’s amenable to the steady breaches of privacy that a president must endure.

“If you were running for office, this is what I’d say to you,” says Bob Kerrey, now head of the New School. “At some point, arriving in your life is an organization called the United States Secret Service. And when the Secret Service arrives, you can’t open your own car door. They interfere with all your neighbors; anyone who wants to get in contact with you has to deal with them. So the best advice I could ever give to a candidate is, Think about this. You might win.”

“The moment I remember,” Kerrey continues, “is discovering that Bill Clinton wanted to live in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. He had intentionally overnighted there when Jimmy Carter was president. He knew where the living spaces were. He knew what they looked like. He had a feel for what that experience was going to be, and it made him feel good. Whereas when I got to thinking about living at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, it gave me the chills.”

What about it?

“What about it? I was single.”

And this suggests the biggest distinction between candidates like Kerrey and McCain versus candidates like Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan. It’s true that both have the same front-stage and backstage personas. But for people like Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, the front-stage persona is the person backstage. Clinton especially: Even when the cameras aren’t rolling, he’s always performing. The fantasy about Clinton is that he’s exactly like you or me. But he’s nothing like you or me. After I followed him around Africa for seven days in 2005, this, to me, was the most startling revelation. Even in the most solitary circumstances, he lit up like a Christmas tree. He enjoyed performing in these quiet circumstances, often repeating the same jokes and anecdotes, including ones that had already appeared in his autobiography. It was like an imaginary camera was always rolling. Everything he said seemed meant for a dais.

Reagan, though less pyrotechnic in style, had a similar openness. Deaver points out, “His whole adult life had been public.” And by the time he became president, adds Ed Rollins, another one of his advisers, “having 10,000 people clapping for him didn’t do anything unusual to him. Some people, the adrenaline gets them so high they ramble.”

Or yelp, as was the case of Howard Dean—Yeeeeeeeow!

And in that yelp is the difference. For politicians like Dean, McCain, Kerrey, or (yes, sorry) Ross Perot, their backstage personas were what they trotted out front, not the other way around. For Dean, this meant we saw arrogance, hotheadedness, and a teenager’s response to a screaming crowd (Yeeeeeeeow!) in addition to his candor and passion. With Perot, we saw a barking loony. With Kerrey, we saw ambivalence (his Senate colleagues called him “Cosmic Bob”) and dread about losing his privacy. And with McCain, we see anger and irreverence.

These are all emotions we associate with private settings. They are not ones we generally haul out for public view.

Yet in almost every campaign cycle, the press has a brief romance with the candidates whose backstage personalities are also out front. They are invariably the most entertaining people as well as the most relatable. But they seldom hold up over the long haul. The rougher parts of themselves eventually start to worry us. “I would muuuuch rather have a phony, competent person in the White House than an incompetent, authentic person,” says Kerrey. “I’m not sure the two aren’t correlated: The greater competence you’ve got, the more you’ve got to be phony in order to get the job done. I want my president to put a mask on. When they’re negotiating for a national-security agreement? Put the mask on. When they’re negotiating with Congress? Put the mask on. If someone says to me a politician is phony, my response, at some point, is, ‘Well, they gotta be. That’s their job.’ ”

This front-stage–backstage distinction is a weirdly good predictor of who survives presidential races, and probably forces us to rethink what authenticity means in politics—and who, in 2008, might survive over the long haul. Obama, for instance, doesn’t suffer using this guideline. Even backstage, in one-on-one interviews, he’s smooth, collected, disciplined, in control.

Perhaps more surprising, though, is that Hillary doesn’t necessarily suffer using this guideline either. Like many people, I used to assume that it was public life, and more specifically the unique constraints of her marriage, that made her build a carapace around herself. And I’m sure it’s partly true. But people who’ve known Hillary a long time say her emotional life has always been opaque. As far back as Wellesley, her peers were in awe of her composure, trying to figure out who she was underneath. Though there probably is another Hillary buried somewhere in her, she’s spent so long in her current role that she’s more or less internalized it, the way soldiers internalize their place in the army.

Last month, the Times reported that Hillary has hired a communications consultant who trains his clients to “jam” and “get to cool.” It’s a rotten idea. Hillary may as well lead with her weakness, as she did in her Senate race, embracing the fact that she’s contained but serious about the job. If she can convince the public that she isn’t a cold schemer, but simply a woman of purpose and reserve—that that’s who she is, front stage and back—she has a shot. (It’s certainly one possible explanation for her strong poll numbers.) It might even be the ideal for the first female commander-in-chief.

McCain has the opposite problem. As exhilarating as it would be for someone as candid as he is to step into the Oval Office, voters would have to radically depart from their previous patterns to choose a man whose backstage rawness was in full frontal view. Right until September 10, New Yorkers would have said that Giuliani’s backstage rawness was in full frontal view, too (as when he told a ferret-loving talk-show caller, “There is something really, really very sad about you”). But the events of September 11 recast his front-stage persona from bully to hero, and as the Times pointed out last week, he’s been extremely disciplined on the trail, keeping his cheerful insults to a minimum. (And this may explain his good poll numbers.) Though many, especially New Yorkers, are still waiting for the other Rudy, the sharp-tongued and freewheeling egomaniac (in the manner of most New York City mayors), to reappear.

One of the most stunning asides Goffman makes in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life is based not on his own observation but that of Robert Ezra Park, a founder of the Chicago School of sociology. He noted that the word person itself comes from the Latin word persona, or actor’s mask. “Insofar as this mask represents the conception we have formed of ourselves—the role we are striving to live up to—this mask is our truer self, the person we would like to be,” Goffman quotes him as saying.

Viewed in this light, the performances our politicians give aren’t necessarily cynical but aspirational, idealistic even: Some are using this process to become the person they think they’re meant to be. All the butter sculptures and corn dogs and ceaseless repetition of platitudes—this bizarre, debasing torture of our candidates—may actually contribute to something positive. Phoniness may just be a kind of chrysalis, a stage a politician must pass through in order to become presidential. The trouble is, not all of them make it.