From the November 25, 1974 issue of New York Magazine.

William Walter and David Hopkins, the Huntley-Brinkley of Grand Junction, Colorado, looked into the perfect blue sky above the Continental Divide as a dot of black expanded into a silver jet roaring over mountains, mesas, and, finally, silhouetted horsemen.

“There it is! There’s Air Force One!” they told the listeners of KREX, the Voice of the Intermountain West. “Here it comes, landing full flaps… .” “It’s touched down… .” “It’s only, maybe, I would guess 300 yards from us, Dave…” “It’s turning toward us….” “They’re rolling up two ramps, one to the front and one to the back. We’re walking toward the plane. We’re walking toward the plane now. Which ramp will the president use?…” “Probably the back, Bill… .” “The president of the United States will be out any moment now… .”

Unfortunately for KREX fans, the president was already out. He had come down the front ramp, as always, and Walter and Hopkins had just walked right by Gerald R. Ford. Actually, Walter and Hopkins were not supposed to be out there on the tarmac, but then Gerald R. Ford was not supposed to be the president.

It was something like the joke the president tried to tell in Indianapolis. He began a speech there by saying that he was traveling around the country because his advisers said he needed more visibility. Then he was supposed to say he passed a lady in the hall who said, “You look familiar,” and he helpfully answered, “Jerry Ford?” Then she said, “No, but you’re close.”

Unfortunately, what Ford told the Indianapolis crowd was that he answered, “I am Jerry Ford,” and the lady answered, “No, but you’re closer.”

Oh, well. On to Grand Junction and the crowning of the Mesa College homecoming queen. “A college homecoming is a happy time and I wish Meesa College …”

Students and friends let out an embarrassed little gasp at the mispronunciation, but Ford recovered quickly, “Messa College.” Oh! “Mesa?” the president said. “Well, we have some community names out in Michigan all of you could not pronounce, either. I love you, anyhow.”

So it went as President Ford traveled 16,685 miles campaigning for Republican candidates in the month before Election Day, 1974. It was a big story—Nightly News, Page One!—with airport announcers parodying The China Trip at every stop. But journalism has its limits. Journalism is covering something, even when there is nothing. There is no accepted technique that deals adequately with the president’s travels. Do you write:

Grand Junction, Colorado, Nov. 2—President Ford had nothing to say and said it badly to a friendly and respectful but slightly stunned crowd of 5,000.

It is not a question of saying the emperor has no clothes—there is a question of whether there is an emperor.

This, then, is one report of the last 9,545 miles of the travels of the president of the United States, from October 24 to November 2:

Des Moines, Iowa. Oct. 24.

The basic Ford message is delivered from the steps of the Iowa State House and at a Republican fund-raising lunch in the Val Air Ballroom, across the street from the national headquarters of Roto-Rooter:

“I know there are some so-called experts who say the president ought to sit in the Oval Office and listen to bureaucrats telling him what to do, yes or no, or sitting in the Oval Office reading documents that are prepared by people in Washington. I reject that advice. It is more important that I come to Des Moines… .

“I remind you a government big enough to give us everything we want is a government big enough to take from us everything we have… . What we need is not a veto-proof Congress. What we need is an inflation-proof Congress.”

On the flight to Des Moines, the president’s press secretary, Ron Nessen, tells reporters that Ford has no plans to visit Richard Nixon next week when he campaigns in California.

Chicago, Illinois. Oct. 24.

After being greeted by Mayor Richard Daley and Miss Teenage Chicago, Diane Weinbrenner, the president attends two Republican cocktail parties before sitting on the dais at the Illinois United Republican Fund dinner. He sits there an hour and thirteen minutes, smiling and applauding as a series of candidates predict that they are going to defeat the Democrats in Cook County.

Grand Rapids, Michigan. Oct. 29.

Breathes there a man with soul so dead who never to himself has said: “Someday I’m going to show them”? Today, Gerald Ford returns to his hometown for the first time as president of the United States.

The president’s homecoming schedule, however, looks the same as it has most days this month, except that he leaves the White House later than usual, at 2:50 P.M. by helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base for the trip on Air Force One: Kent County Airport at 4:35; Calder Plaza for a rally at 5:05 and presentation of homemade cookies and a replica of a Lincoln table; Hospitality Inn for a Republican cocktail party at 6:20; presentation of a Shriner fez at 7:25; meeting with labor leaders at 7:30; meeting with G.O.P. congressional candidates at 7:45; Calvin College for a Republican rally at 8:27 and presentation of a painting and wood-carving; airport at 9:50 and presentation of a Fraternal Order of Police membership; back to Washington at 11:30.

The homecoming seems surprisingly unemotional—or. perhaps. Ford and the people who knew him when are just stolid folk. It is a dreary, rainy night and the president says that “words are inadequate to express everything I feel deep down in my heart.” Certainly his words are—and things aren’t helped when he pledges “my heart, my soul, my conviction, my dedication” to the election of a congressional candidate named Paul Goebel Jr., who he later admits privately is something of a clod.

Lyman Parks, the mayor of Grand Rapids, opens the ceremonies by thanking Michigan Governor William Milliken for interrupting his busy schedule to come to town, but, curiously, no speaker ever mentions Ford’s schedule.

“… The assumption of the White House press is, ‘What the hell, it was Jerry talking about things he doesn’t understand’…”

The president’s delivery is as flat and stumbling as usual, and, as usual, the crowds give him far more applause before he speaks than after. At the Calvin College Republican rally, Christian High School cheerleaders are used to rehearse the crowd’s cheering and applause for an hour before Ford arrives. The White House transcript of his remarks is later edited to make a little more sense. The “as delivered” text, for instance, indicates the president said of World War II: “We got involved in a contest between freedom on the one hand and the effort on the part of some to subjugate people on the other.” Actually he said, “We got involved in a contest between freedom on the one hand and liberty on the … and … and … and … the effort to … to the effort on the part of some to subjugate people on the other.”

Back at Kent County Airport, however, there are several hundred people waiting to see the president in a downpour. With Secret Service agents scrambling to hold an umbrella over him, Ford sloshes through mud and small rain lakes to shake hands for twenty minutes, saying, “Hi … Hi … Good to see you … Thank you.” On the plane back to Washington, Nessen says Ford has learned that Nixon is in critical condition in Long Beach but the new president has no plans to visit his predecessor next week in California.

Sioux City, Iowa. Oct. 31.

On the flight from Washington to Sioux City, Nessen says the president has no plans to visit Nixon tomorrow in California. The press secretary also emphasizes that there has been no change in United States policy toward Palestinian refugees, even though the president, at a news conference the day before, had seemed to back off the U.S. position that all negotiations on Israeli-occupied territories on the west bank of the Jordan River must include only Israel and Jordan, by saying: “We, of course, feel there must be a movement toward settlement of the problem between Israel and Egypt on the one hand, between Israel and Jordan or the P.L.O. on the other.”

Whatever the president meant by that—he seemed to be equating the legitimacy of Jordan and the Palestine Liberation Organization—the White House press corps doesn’t take the thing particularly seriously. The unstated assumption is that Henry Kissinger handles American foreign policy. One senior correspondent says: “What the hell, it was just Jerry talking about things he doesn’t understand.”

On the ground in Sioux City, Don Stone, the public-relations director of the Northwestern National Bank, is rehearsing crowd cheers: “Now when I say ladies and gentlemen, the president of the United States, I want you to …”

When Ford descends to say a few nice words about Wiley Mayne, one of the least impressive members of the House Judiciary Committee, the president says: “A few days ago I went to my hometown. We had a wonderful reception, but I can say without any reservation or qualification, the reception here is just as enthusiastic, just as warm.”

That’s about right—and people beyond the tenth row are talking to each other in small groups as he says it. Ford tells the crowd not to pay any attention to a Des Moines headline that says FORD HAS NO FARM PLAN. He says he does have a plan and begins to list a series of existing laws and agreements “I will strictly enforce.”

David Murray of The Chicago Sun-Times files this lead: “President Ford came to Sioux City today to tell Iowa farmers what he is not going to do to relieve their economic problems.”

Los Angeles, California. Oct. 31.

At 7:16 P.M., Nessen announces that the president has just telephoned Mrs. Richard Nixon in Long Beach and said: “I don’t want to push, but would it help if I came down there?” Nessen said Ford was checking to see if his schedule allowed him time—in fact, there has always been a suspiciously blank spot on the schedule for the morning of November 1.

After meetings with Governor Ronald Reagan and a couple of cocktail parties, the president goes to a $250-and $500-a-plate Republican dinner at the Century Plaza Hotel. It’s a rather classy affair and as I walk into the hotel, a man in a Cadillac asks, “Do you park the cars around here?”

The president sits on the dais for an hour and 38 minutes listening to a succession of local Republicans, Bob Hope, and the music of Manny Harmon, who says Ford asked him to play the songs from Oklahoma!

Hope is very funny, perhaps closer to the truth than he knows: “The president and Henry Kissinger are both early risers. Whoever gets to the airport first gets the plane.” The press, at least, are absolutely convinced that Ford is traveling to avoid being president. Nessen, battered by questions about who’s running the country, says, “Look, he enjoys this. He’s having a good time.” Ford himself adds that he enjoys the food at political dinners.

Los Angeles, California. Nov. 1.

At 8:15 A.M., Nessen announces that Ford will leave at 9:35 to visit Nixon. In talking later about the visit, Ford always refers to Nixon as “the president.”

Fresno, California. Nov. 1.

There are worse public speakers than Gerald Ford—Representative Robert Mathias is one. It’s shattering for everyone who remembers Bob Mathias of Tulare, California, winning the decathlon in the 1948 London Olympics, but Congressman Mathias is reading slowly when he says: “I’m proud to be your representative. Frankly, I’m anxious to get back to work… . Please get out and vote.”

Ford follows that with an inadvertent double entendre: “This big valley … to serve its people in Congress it produces big men, mentally and otherwise, in Bob Mathias.”

Anyway, Mathias still looks terrific at 44 and the signs in the airport crowd are creative: U.S. GET OUT OF NORTH AMERICA… PARDON ME, PINHEAD… FOLLOW YOUR PRESIDENT: STARVE … I’M BORED WITH FORD.

The president is having even more trouble than usual with the language. He says judgment as “judge-e-ment,” almost with an Italian accent; athlete becomes “ath-e-lete,” with the same accent; seance becomes “see-ance,” and the capital of California is someplace called “Sacer-emento.”

“This guy’s going to Vladivostok?” says George Murphy of The San Francisco Chronicle.

Portland, Oregon. Nov. 1.

The president’s staff is furious when Air Force One lands in Portland—Ford has been taken by someone named Diarmuid O’Scannlain.

O’Scannlain is the Republican candidate for Congress in Oregon’s First District and he appeared in Fresno to hitch a ride north on Air Force One. He then wanted to talk to Ford, and did, for a couple of minutes—then he ran back to the press section of Air Force One and said he had just told the president of the United States that he was wrong to pardon Nixon and wrong to propose a 5 per cent income-tax surcharge.

On the flight, Ford also looks over a cable from Kissinger outlining the secretary of state’s speech next week to the World Food Conference in Rome. The president does not review all Kissinger speeches, Nessen says, but he does see “major” ones, and the press secretary says the incident is proof that the president is the president no matter where he travels.

At the Benson Hotel, the president meets with six representatives of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association and receives a $10 beef gift certificate, which someone says he can use to buy bacon.

“I love beef,” the president says. “I’m a great advocate of it. But I don’t know about breakfast.”

“There is such a thing as beef bacon,” a cattleman says.

“Really?” Ford answers. “Is it a special part of the cattle?”

After the usual round of Republican receptions, Ford heads for the annual auction of the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, a black-tie fundraising affair in the Portland Coliseum. Boats and even airplanes are being auctioned off to a handsome, champagne-drinking crowd that seems pretty recession-proof. The president is there 25 minutes—he autographs two footballs that bring $2,700 each; one pair of his cuff ‘links goes for $11,000 to a lumber dealer, and another goes for $10,000 to a food distributor.

It is a high good time. Ford is bouncing around like a kid, and when the bidding on the first football reaches $500, he grabs the microphone and says: “Double it and I’ll center it to you.” Which is exactly what the center of the 1934 Michigan team does—after moving around when he suddenly realizes three dozen camera lenses are focused on what his quarterback used to see. Finally, an auto-parts dealer pays $1,100 for the chair Ford had sat in for a moment.

Salt Lake City, Utah. Nov. 2.

Radio and television are waiting, of course, when Ford arrives at Salt Lake City International Airport at 10:35 A.M. Howard Cook of KSXX Radio sees it this way:

“The president of the United States is not just President Ford, a Republican. He is an institution. He is the most powerful man in the world. You say what about the Russians? They have the same power we have, but there it takes more than one man to pull the trigger. Here we’re set up so that one man can do the job. He would never dream of doing it, of course, but it’s within his power.”

The man with the power is introduced to 8,000 people at the University of Utah by Jake Garn, the mayor of Salt Lake City and Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate, who tells a charming and revealing story of a meeting between fourteen mayors and Ford just five days after he succeeded Nixon:

“We were just standing around talking and somehow the president slipped into the room and came up behind me and said, ‘Hi, Jake, how are things in Salt Lake City?’ Then he walked around the room, shaking hands and saying, ‘Hi, I’m Jerry Ford.’… When the meeting was over, someone asked, ‘Is there anything we can do for you. Mr. President?’ He said: ‘Go home and pray for me. This is a very big job.’ “

“… On November 17, Ford will take the road show overseas. ‘Wait till the Russians get a load of this,’ someone says …”

Grand Junction, Colorado. Nov. 2.

I don’t think there is a reporter traveling with Ford who does not personally like the man. But this has not been an inspiring month, and the talk is getting brutal. A first-timer on the Ford trail asks an important White House correspondent, “Hey, Nixon was ‘Searchlight’; what’s Ford’s Secret Service code name?”

“Dummy!” says the senior man.

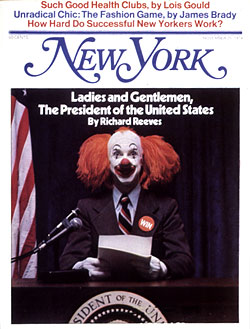

His fellow travelers are routinely calling the president “Bozo” or “Bozo, the Clown.” On the flight to Grand Junction, an important political reporter almost shouts: “I can’t believe this. There is no way I can get what’s going on into the paper. He’s Lennie. I’m telling you he’s Lennie in Of Mice and Men. I can just hear him at the hospital with Nixon—’Tell me again about the rabbits, Dick.’ “

Driving into Grand Junction, we see two little girls in pigtails, standing on a rise with a pony. Between them, they hold a long sign that says, PARDON, BAH!

Speaking to about 5,000 people and twenty high-school bands in the Lincoln Park Baseball Field, Ford runs into trouble as soon as he crowns Diane Poster, a pretty twenty-year-old blonde, the new Mesa College homecoming queen, and gets a laugh by pretending to write down her phone number. It’s time for farm talk, and as he often does in steer country, he begins by talking about cows: “I suspect there are a few dairy farmers in this group. How many are here?”

One guy yells out.

Then the president starts talking about the unfairness of American farmers’ having to compete with foreign farmers who are subsidized by their governments:

“We will challenge him on the open fields, head to head, and we will do all right. Some of the foreign governments in Western Europe have been doing, by what they call countervailing duties, subsidizing dairy products in their countries. We won’t stand for it and if they are going to do that, we will challenge them, head to head.

“In the meantime, Japan, Western Europe, Canada has imposed arbitrary limitations on the export of American products to those countries. I will say to you, they are not going to limit our imports, and we are going to hold the line on exports to the United States.”

To a city boy, the message finally got through: no country but the United States has the right to subsidize farmers or limit imports. And, food prices are going to keep going up. It would probably be going too far to infer that we would invade Canada if it doesn’t shape up.

Finally, he winds up by saying that electing Democrats to Congress would create a “legislative dictatorship” and closes with a civics lesson that has Freudian overtones: “You know we have three great branches of this government of ours… . We have a strong president, supposedly, in the White House… .”

Wichita; Kansas. Nov. 2.

While the president visits two Republican receptions and a Shriners meeting, David Owen, the lieutenant governor of Kansas, entertains 4,000 more waiting Republicans at the Century II Convention Center. “They tell me I have to fill a few more minutes before the president arrives. Well, I hate to tell Polack jokes, but these are Polack stories… .”

Ford spoke for 28 minutes. When the transcript of his remarks was prepared, I said to someone on the White House staff: “You know, the whole first page doesn’t really make any sense.”

“Wait till you see the second page,” he answered.

These are the highlights of the official transcript of the first page:

“It is great to be here despite the weather. I love you. Thank you.

“As Bob was going through the process of making the introduction, I tried to think of how many times, how many places I have been in Kansas in the last 25-plus years as a member of the House, as Minority Leader, as Vice President, and President.

“And I wrote down, I think, most of them—I am sure I missed some—but we went out to Great Bend. Wasn’t that wonderful out there last year? It rained there too, but that was all right. But I have been in Dodge City, and you know what they do to you in Dodge City… . Well, I like Kansas.”

On the flight from Wichita back to Washington, exhausted reporters look over the schedule for the president’s next campaign. On November 17, he will take the road show to Japan, Korea, and Russia. “Wait till the Russians get a load of this,” someone says. “When they thought Kennedy was a clown in Vienna they put missiles in Cuba. This time it might be Long Island.”

Air Force One lands at Andrews Air Force Base early on Sunday, November 3, and the president of the United States is back at the White House at 1:15 A.M.

The press back-up plane—six “pool” reporters travel on Air Force One—touched down at Andrews about an hour later and 30 reporters headed for home, hearth, and wife. Like a lot of young newspapermen, I was once told by a city editor that the lead of a story is what you tell your wife when she asks you what went on that day. I am willing to bet that on that particular late night what reporters were telling their wives was a hell of a lot different from what they had been writing.

What would I say at home? I would choose my words carefully and say, “The president of the United States is a very ordinary man.” He is, in a phrase coined by Saul Friedman of the Knight Newspapers, our “Commoner-in-Chief.” It is not hard to walk by him without noticing, as Bill Walter and Dave Hopkins did in Grand Junction.

President Ford stayed in Washington for fourteen days before taking off on his first foreign trip—the first of many, according to some of the men close to him. Our last president was a recluse; this one cannot stand being alone. Much of his Oval Office time was spent in post-mortems of the last trip and briefings for the next.

Welcome home and sayonara, Mr. President! There are times, and this is one of them, when Herblock is deeper than The New York Times. We have always cherished the promise that any one of us could be president. Any one of us now is.