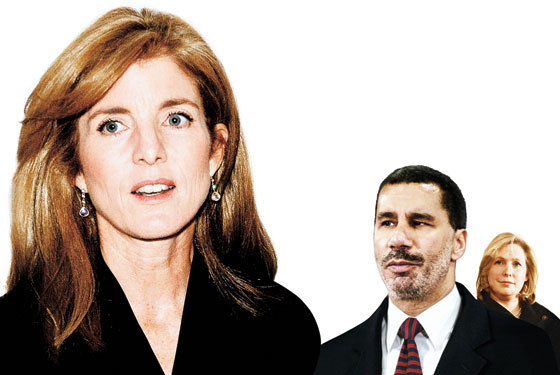

Caroline Kennedy was missing. For about five hours last Wednesday, as her wildly unlikely bid to become a U.S. senator was on the brink of collapse, one of the city’s most famous women disappeared. At 3 p.m., Kennedy had set off a political and media cataclysm with a single, out-of-the-blue phone call to Governor David Paterson from her Park Avenue apartment.

Seven weeks earlier, she’d upended a lifetime of privacy along with the race to replace Hillary Clinton by calling Paterson to declare her interest. Kennedy’s candidacy had been a weird ride ever since, but she’d bounced back from early mistakes. Now, the day after the inauguration of her friend President Barack Obama, her aides were discussing plans for the triumphal press conference.

Until Kennedy called Paterson to say she was pulling out. “Personal reasons” had emerged that made it impossible for her to accept the Senate seat. She was sorry, but she was done. Paterson told her to think it over and call him back. And then she vanished.

As the news erupted on the New York Post’s website; as Kennedy’s political aides frantically called and e-mailed her; as her stunned friends wondered whether this was some kind of dirty trick from one of her rivals to force Kennedy from the contest: Silence. Was Caroline Kennedy holed up at home wrestling with her options? Was she arguing with her husband, Ed Schlossberg? Was she having some kind of breakdown, caught between the warring voices of her parents—her father, the embodiment of the Kennedy political hunger, and her mother, who’d raised Caroline to fear the costs of that hunger? Had she realized senators can’t spend August on Martha’s Vineyard?

She resurfaced about 8 p.m. A conference call was arranged with close friends and political advisers. Kennedy wavered—she wasn’t sure what to do. And she wouldn’t specify what the “personal reasons” might be. Finally, just after midnight, the definitive word was sent to the media by e-mail.

And Governor Paterson? The man who had turned the search for a new New York senator into the defining circus of his rookie year in office and was now in danger of having it escalate into a bizarre embarrassment? His behavior was nearly as peculiar: At one of the most important moments of his political life, he decided to … go to bed. Paterson didn’t learn about Kennedy’s decision until the next morning.

The appointment was destined to be a mess—how could it not be? The cast of characters involved in choosing a new junior senator for New York included a lapsed priest, three of the country’s most bare-knuckled political dynasties, and an imperious mayor. Add to that a $15 billion budget deficit and a tainted plate of sushi. And start the whole crazy chain of dominoes with a hooker.

Yet in two months politics in New York devolved from dysfunctional to chaotic, tarnishing every major player involved. And sometimes it seemed that David Paterson wanted it exactly that way. His style of governance, a dizzy mix of ingratiation and trickeration, has turned what could have been a moment of triumph—a powerful new ally in the Senate, a relationship with President Obama—into a slapstick fiasco, a fitting sequel to the way Paterson got the job in the first place. Politics is often a contest of half-truths, where the winner is the best bullshitter. But thanks to Paterson and a cast of dozens, the fight to become the next senator became instead a world-class festival of lies.

For Caroline Kennedy, it was a bizarre rise and fall, an entire political career telescoped into seven weeks. Kennedy seemed to have an almost Victorian idea of rectitude and an extreme squeamishness about personal revelation, lessons about propriety drilled into her by her mother. But for all the care she’d devoted to maintaining a zone of privacy around herself, she ended up as sullied as any lifelong politician—with many of her wounds self-inflicted. From an elegant if slightly bloodless cipher, she’d become David Paterson’s comic foil.

It was the night before Super Duper Tuesday 2008, and Barack Obama’s campaign was surging—largely thanks to the stunning endorsements he’d received, one week earlier, from Ted Kennedy and, more surprisingly, from Ted’s niece Caroline. The crowd of 17,000 in the Hartford Civic Center stood and roared as they beheld a very rare sight: Caroline Kennedy, her generation’s closest thing to Greta Garbo, walking to the microphone.

Off to one side of the floor, in one of the arena’s tunnels, Obama’s political mastermind, David Axelrod, struggled to be heard over the ecstatic din. “Ted Kennedy is a link to a time when our politics had such meaning and possibility and people felt differently about it than they do today,” he said. “As for Caroline’s endorsement, someone said to me she’s the purest brand in American public life.”

That was because she’d nurtured her mystique by studiously avoiding the grubby side of politics. Kennedy had written or compiled seven books, and in 2002 she agreed to head fund-raising for the city’s public schools. After two years of part-time work, though, she retreated again to raise her three children and serve on the board of arts groups and charities, a kind of watered-down Mrs. Astor figure. Within her family, though, Kennedy could be just as competitive and politically savvy as the more outgoing members. “She’s always been very up on politics,” Kathleen Kennedy Townsend says. “There’s a difference between running for office and being knowledgeable about politics. Caroline is very smart and very interested and quite astute.”

But the overriding principle of Caroline Kennedy’s life had been one of sphinxlike silence. It could manifest as shyness, though at bottom it was a kind of policy toward her potential celebrity—private was private; in public, you wore a mask. “You can’t separate Caroline’s personality from her experiences,” says her longtime friend the novelist Alexandra Styron. “She’s very smart, very savvy; she’s learned to read a room quickly and tell when she’s safe and when she isn’t. Over time, she’s found more ways to operate out in the world in a more confident way—to be her best self out in public. But it’s taken a long time for her to grow into that.”

Styron’s mother and her father, the writer William Styron, were friends with JFK and Jackie beginning in the late fifties; Al Styron and Caroline Kennedy became close as adults. “When my father died, Caroline was the first, or one of the first, to call,” Styron says. “Often when you lose someone, people are not sure what to do—they don’t want to bother you, they don’t want to impose. Caroline didn’t wait. She comes from a place of deep experience with loss, and so she doesn’t waste a moment in being there for people when they’re in pain.”

Kennedy has been shaped by trauma. Her father’s murder and her brother’s death in a plane crash were wounds that were exponentially compounded by being so very public. Yet it was her mother, the most famous woman in the world, stalked by tragedy and by Ron Galella, who trained her to be always on her guard. Jackie’s fierce protection of her children produced two sane adults and provided something of a template for raising a family with good values in the public eye.

Caroline’s most rebellious act as an adult was marrying the older, Jewish artist Ed Schlossberg in 1986. But even their marriage has functioned as something of a cocoon. “Ed is her rock, and he always has been,” Styron says. “Ed is deeply cautious and very protective of her. He’s the organized, neat one, the one who makes sure the doors are locked and the seat belts are on. It gives her the opportunity to be lighthearted. He’s the sentry, in a way. He allows her a base from which to venture out into the world.” For the last year, various gossip outlets have speculated about the state of the marriage, but no one has ever substantiated the rumors.

Kennedy’s aloofness from conventional politics gave her endorsement of Obama as the second coming of her father in January 2008 great power. What wasn’t as clear at the time was just how meaningful the role was to Caroline. Now, at 51, with her youngest child 16, she had been thinking about what the next chapter in her life would be.

“Campaigning is heady if you haven’t ever really done it,” says her friend and agent Esther Newberg. “It gets you, and everything else seems less real. And I think Caroline realized that.”

She’d helped make a president, and she’d opened a door for herself. The question was what to do next with her newfound power. Just after Election Day, Obama provided her with an answer. And on December 3, she quietly declared her interest in replacing Hillary Clinton by calling New York’s governor.

David Paterson likes to open with a joke. It’s an ice-breaking tactic straight out of the hoary toastmaster’s bible, of course, but for Paterson, humor is a more complicated tool. He learned a long time ago the social awkwardness his blindness can create, especially when someone is meeting him for the first time. Yet Paterson wants to do more than cut the tension; he wants desperately, even more than most politicians, to be liked. Almost as much as he wants to be taken seriously.

The competing impulses have ruled Paterson’s life since he was a child. He was born into an elite New York family; his father, Basil, was a member of the “Gang of Four” that dominated Harlem politics. When Paterson was 3 months old, an infection destroyed the optic nerve in his left eye and severely limited the vision in his right eye. That he went on to graduate from Columbia and earn a law degree at Hofstra without ever learning Braille is testament to Paterson’s intelligence and determination. After college, he signed on with the 1985 Manhattan borough-presidential campaign of David Dinkins, one of his father’s closest friends. He’s depended on, and resented, the Gang’s help for most of his political career.

Last March, the world discovered Ashley Dupré and, shortly thereafter, made the acquaintance of David Paterson and his sense of humor, his remarkable working methods, and his dalliances with a co-worker at a Manhattan hotel. The circumstances of his own promotion from lieutenant governor only amplified his need to be his own man. The senatorial appointment became a kind of test case. “The last thing David Paterson wanted was this process to make it look like he was being rolled,” says a state Democrat who knows Paterson well. “He’s African-American, and he’s blind, so he’s been underestimated his entire life, so he wants to show he’s in charge. Look at how he travels: At the Democratic convention in Denver, you’d see Jon Corzine and he’d have two people with him. You’d see David Paterson and he’d have 60 people with him.”

But the pol, with a laugh, added a note of warning. “I’ve known David for twenty years, and he takes great pleasure in twisting people up and confusing them. He’s made many, many decisions in his life where people afterward said, ‘What the fuck?’ ”

Kennedy’s big black borrowed GMC Denali was racing west down the Thruway from Syracuse to Rochester. It was December 17, and she was in the front passenger seat, glancing out the window at the featureless gray sky and lumps of dirty snow. Kennedy had just made her first official visit as a candidate to replace Hillary Clinton. Her short chat with the mayor of Syracuse had been pleasant enough. Suddenly, though, there was a commotion in the back seat.

Her political consultant, Josh Isay, was squinting at his BlackBerry in alarm. Ten minutes after they’d left Syracuse, the New York Times’ website posted a story. “In a carefully controlled strategy reminiscent of the vice-presidential hopeful Sarah Palin,” read the first sentence, “aides to Caroline Kennedy interrupted her on Wednesday and whisked her away when she was asked what her qualifications are to be a United States senator.”

Kennedy had emerged from her meeting with Syracuse mayor Matt Driscoll to find a scrum of twenty reporters and cameramen elbowing for position between the office Christmas tree and a secretary’s cubicle. She’d stopped and improvised a bland 30-second statement, her eyes darting all over the room. Dashing for the door, Kennedy looked more like a perp than a potential U.S. senator.

From the moment she had called him, she was the front-runner for the job. Her choice would have solved many of Paterson’s problems, allowing him to avoid choosing among warring small-fry congressional contenders; unlike Andrew Cuomo, she’d be his candidate, his senator; and her appointment would make the kind of dramatic splash he sought. The media mob that followed her everywhere was evidence of that. But she was a risk—and he wanted her out proving herself, floating like a human trial balloon. Paterson had told her to go upstate and introduce herself to some elected officials, even dictating the order of the cities Kennedy should visit. Crazily, he’d also told her not to take questions from the media. (Paterson now denies having instructed her.)

As the SUV cruised, a call was placed to Albany. Paterson couldn’t be reached. Kennedy and her team decided that stiff-arming the press was untenable and took a few questions in Rochester and Buffalo. A peculiar dynamic had been set in motion: missed communications and mixed signals between two protagonists who had spent their starkly different lives being obscure.

Just as the uproar from the upstate trip was settling down, Kennedy’s bid was hit with a new barrage of criticism, and this one showed how much anger she’d stirred among the state’s Democratic Establishment. Gary Ackerman, a Queens congressman, told a radio interviewer that Kennedy was as qualified as J.Lo—a celebrity and nothing more. Other Democrats were attacking with more sophisticated subterfuges, using surrogates, covering their tracks. This was partly because at least ten other New York politicians—including Andrew Cuomo, Carolyn Maloney, Tom Suozzi, and Steve Israel—thought they should be first in line for the job. But Paterson said he wouldn’t name HRC’s successor till she was officially gone. So he didn’t do what a normal politician might have: make the decision and be done with it.

“If he would have named someone early on, people would have gotten behind it,” one New York political strategist said midway through the saga. “Instead, not only didn’t he pick someone, he went in reverse—he told Randi Weingarten maybe she should be senator. He meets with Liz Holtzman, who actually thinks she can be a senator now. So now people have to rip the front-runner. Because in this campaign, you can’t be seen as openly promoting yourself, so all you can do is the negative part, making sure your surrogates, or unnamed sources, are ripping the shit out of the other people.”

It was partly to combat forces like these that Kennedy hired Josh Isay. Isay, 39, had risen through the ranks of Chuck Schumer’s Senate aides, eventually becoming chief of staff. In 2002, Isay left government to co-found Knickerbocker SKD, a powerhouse consulting and lobbying firm whose clients included Bloomberg’s 2005 reelection campaign. Kennedy had met Isay when he did some work for the public-school fund-raising drive. Isay’s connection with Schumer helped fuel the belief that Kennedy was Schumer’s candidate, too—and that Schumer particularly wanted to make sure Andrew Cuomo didn’t become yet another junior senator with a higher political Q rating than he had.

A more shadowy player in the drama was Charles O’Byrne. As a Roman Catholic priest, O’Byrne had officiated at the wedding and funeral of Caroline’s brother. O’Byrne quit the priesthood, however, and came out as a gay man. In 2004, he went to work on the State Senate staff of David Paterson and rose to become Paterson’s most trusted consigliere and his hot-tempered enforcer. O’Byrne was chief of staff to the accidental governor until the fall of 2008, when his failure to pay taxes for five years became a scandal. His resignation was an enormous destabilizing blow to Paterson’s operation in Albany. But O’Byrne remained in contact with Paterson and became an emissary between the governor and Caroline Kennedy.

Isay quickly assembled a packed schedule of calls and meetings for Kennedy with the state’s power brokers—some of them obvious, many not. Kennedy’s team expected her to go through a rough baptism by press. But in any conventional campaign, the candidate can fight back with ads, speeches, listening tours. This time, her aides say, Kennedy was required to defer to Paterson’s shifting limits on what she and her competitors could do or say in pursuit of the Senate opening.

Kennedy’s camp debated how to maneuver. “Once Hillary Clinton says she’s gonna resign her seat, there’s a campaign for this job. There just is,” says one adviser who favored playing hardball from the beginning. “So as soon as Caroline expresses interest, she has ten people who are trying to kill her. Two of which are the Cuomos and the Clintons [still resentful of Kennedy’s endorsement of Obama], the two most vicious political organizations in the country in our lifetime. She can do one of two things: She can sit back and do nothing and just let people beat the shit out of her. Or get out there, in a subdued fashion. But you also play the game behind the scenes.”

Kevin Sheekey, Mayor Bloomberg’s political aide, was calling labor leaders, making the case for Kennedy as the front-runner and as the one choice with hooks to Obama. Conditioned by the cut-and-thrust of a standard campaign, though, Sheekey overdid the pitch, saying Paterson would be guilty of “political malpractice” if the governor chose anyone but Caroline Kennedy. Sheekey was thought to be Bloomberg’s elbows in this campaign, which didn’t help matters, given Bloomberg’s tense relationship with the governor. “Paterson told Kerry Kennedy that he would have appointed Caroline already, except that every time he gets ready to, Bloomberg or Sheekey makes one of these aggressive, nearly belligerent statements,” said a Kennedy intimate in early January.

Bloomberg and Sheekey turned down the volume, but the actions of Kennedy’s many surrogates had a more subtly corrosive effect: They fed into the image of Kennedy—recessive by nature and restrained by Paterson’s non-campaign rules—as a creature completely created by other actors. With all the clashing agendas, Kennedy was becoming a bystander in her own campaign.

With Kennedy out of sight after the brief and unhappy upstate tour, questions kept pouring in. Trying to fend off the calls for information yet play by Paterson’s rules, Kennedy’s campaign dug the hole even deeper, issuing vague written responses to policy questions. As her candidacy foundered heading into the holidays, some of Kennedy’s advisers raged privately at Paterson. With stories about Kennedy’s wealth and spotty voting record dropping daily, her team decided that the risk of angering Paterson paled compared with the continuing damage from staying silent. “You couldn’t put Paterson in a place where he couldn’t pick her,” one of her aides says, “and he couldn’t pick her if we had three weeks of, ‘She’s Sarah Palin, she’s hiding, what is she hiding?’ ”

Round one of Kennedy’s media blitz went well—a December 26 Associated Press interview followed by an appearance on NY1’s Inside City Hall. But the mood changed quickly the next morning. Kennedy walked into a reserved back room of the Lenox Hill Grill, on Lexington near 78th, and sat down with two reporters from the Times. She’d earnestly studied briefing papers on issues like immigration, the economy, education, and gay rights, and she’d been tutored by Ranny Cooper, a PR executive and former aide to Ted Kennedy. Instead, she was greeted with a series of questions on her motivations for wanting to be a senator—and soon became rattled and annoyed, her responses riddled with you knows and ums, which the Times, devastatingly, included in a transcript of the interview. Some of Kennedy’s relatives blamed Isay for not being tougher in readying Caroline for the interview.

Kennedy also smacked headlong into a newly emboldened Times city staff. “We’ve grown a pair of balls, and I’m amazingly proud of the paper,” says a Times reporter. “The turning point was the editorial page’s rolling over for Bloomberg on erasing term limits. The reaction from the reporters and editors is that we’re the last line of defense—we’ve got to hold the line.” Not for or against any particular politician, that is, but to stand up for small-d democracy. After inflating her candidacy by making her simple declaration of interest in the job the lead story of the day, they compensated by hitting her hard.

One larger problem, though, was Kennedy’s lifelong avoidance of anything resembling a personal question—and her delusion that politics is about issues. She had never come to terms with the fact that the reason she was in line for the job was that she was, well, a Kennedy, and that people loved Kennedys, what they ate, where they lived, what they felt about their triumphs and tragedies. Whereas she’d based her entire life on witholding such information. “There’s stuff that she needs to be able to deflect, stuff that no other candidate would get,” a friend says. “This is New York, and they’re gonna come after her. It’s not just going to be about abortion and Indian Point power plant. It’s gonna be all the things that nobody has dared to ask her when she was protected by the patina of being above all this.”

Though Kennedy made hundreds of calls to county leaders and willingly schlepped to outer-borough meetings, she was a novice in the networking aspect of politics. She’s long been a prolific e-mailer, sharing everything from YouTube clips to comments on world events with a circle of friends. Kennedy is less comfortable with the phone. “She’s never had to stay in touch with a lot of people,” says one relative. “She leaves her cell at home.”

Through the entire roller coaster, say her aides, Paterson encouraged Kennedy. He would have liked her rollout to go more smoothly, of course. The Reverend Al Sharpton, one of Paterson’s close friends, was seeing the same positive signs. “She’s got a tremendous amount of support and empathy in the black community,” Sharpton said in early January, “because she appeared to have stood up to the Clintons for Obama at a critical time.” Paterson certainly cared about Kennedy’s support in his home base. Right?

Kennedy’s formal sit-down to discuss the job with Paterson, on January 10, was “a lovefest,” another adviser says. “It was, ‘When we announce this, we want to do this and this and this.’ ” Then the governor added some intrigue. “He also said, ‘By the way, over the next couple of weeks, you’re gonna see me send signals that other people are rising and falling, and it’s just cause I don’t want this to be seen as a fait accompli.’ ”

The morning before Obama’s inauguration, Paterson’s black SUV peeled out across the National Mall. After a brief appearance on CNN’s American Morning, the governor had settled into the back seat of his car to rest before an interview with Capital News 9, an Albany-based cable channel. Then, without warning, his aides scrambled, leaving dust and baffled reporters in their wake.

Later, word was passed that the governor had a serious headache. Later still, Paterson claimed to have eaten some bad sushi the night before. “Right,” says a reporter who covers the state capital. “It’s just more drama from Paterson.”

“Welcome to the world of David,” says an elected official who has known Paterson for years.

The intrigue surrounding Hillary Clinton’s replacement in the Senate made Paterson a hot commodity in Washington—and he was more than happy to turn up the heat. He landed a coveted prime-time chat with Larry King on Sunday night. Monday morning, he went back to CNN. Tuesday, it was Katie Couric over at CBS. More than the pace, though, it may have been keeping his story straight that was making Paterson queasy. Just after Obama’s swearing-in, Paterson told reporters that he had “a good idea” whom he’d be appointing. Two hours later, on national TV, the governor waffled: “I’m not totally sure who I’m going to appoint yet.”

Clearly there was calculation involved: Keeping the speculation alive meant Paterson stayed in the spotlight, a golden gift for a man who hates being characterized as an “accidental governor” and a man who needs to run for the office, for the first time, next year. Often in Washington Paterson seemed simply to be ecstatic that his games with the media were keeping the attention so focused on him. But those who know Paterson well saw something else at work, particularly in his abrupt cancellation of the Capital News interview.

“Stress manifests itself physically with David,” a longtime Paterson adviser says. “In 2006, one night, he was preparing for a big Spitzer campaign swing. He was on the phone when he suddenly had a sharp pain in his chest, and the minute he hung up, he dropped to the floor and couldn’t get up. They took him to the hospital. Same thing early in his time as governor—he was on the plane and had problems with his eyes. When I heard he had a bad headache last week and he was feeling wobbly, I knew the stress of this Senate thing was manifesting itself.”

Paterson’s decision-making was complicated by the Blagojevich affair, which made him want to show that he was being deliberative and deciding the appointments on the merits. “If not for Illinois, this whole thing would have been over weeks ago,” said one consultant. “The president, or Rahm Emanuel, would have called the governor of the State of New York and said, ‘Hey, by the way, she is my person.’ Paterson would have said, ‘Great. I’ll do that for you.’ But now Obama can’t call and Rahm can’t call.” And the state’s dire fiscal situation made the appointment process, with its twists and turns, a welcome distraction.

In Washington last week, Paterson cranked up the fog machine once again: He hadn’t yet read the voluminous questionnaires filled out by the prospective senators, and he didn’t plan on doing so until he returned to Albany on Wednesday. “I would figure by this weekend that we would come up with a candidate,” Paterson said. “I would say I have narrowed the field, but have not, just don’t seem to stay with the same pick for a period of time. In other words, I’ve tried seeing how it works with different scenarios, and I just haven’t settled on it yet.”

Soon he trotted out his latest joke: that he’d settled on Michelle Obama. At the time, Kennedy’s camp found Paterson’s eccentric actions oddly reassuring. “We were skeptical, because we knew his reputation for being unpredictable,” says one of Kennedy’s allies. “But then he did exactly what he said he was gonna do: He’d misdirect, say he hadn’t made up his mind, says there’s other people in the running—while still signalling privately it was her.” But the fun ended abruptly when Paterson and Kennedy got back to New York.

Fred Dicker is a legend in New York political journalism, someone who for years has had more highly placed sources—particularly in Albany—than the rest of the state’s reporters combined. So when Dicker’s byline (along with Maggie Haberman’s) appeared atop a stunning story on the Post’s website last Wednesday night, the article carried more meaning to New York’s political class than simply breaking the bombshell news that Caroline Kennedy was withdrawing. The political pros were reading between the lines to determine the source of the Post’s exclusive. And it sure didn’t look like the news was coming from anyone in Kennedy’s camp. It was yet one more thing that no one understood.

The Times’ website followed and seemed to advance the story: Kennedy’s departure was said to be motivated by her worry for the health of her uncle, Senator Ted Kennedy. But that explanation was risible—scary as Ted’s seizure the day before may have been, Caroline had known about his fragile condition since May, and Ted had been pressing her bid. Within minutes, family members close to Caroline were on the phone to reporters, beating back the withdrawal story. Her call to Paterson, pulling out of the race? “It didn’t happen!” one cousin said. “Kerry just talked to Paterson, and he says it’s not true!” Kerry Kennedy had kept in touch with Paterson during Caroline’s candidacy, and, says another Kennedy relative, Paterson had told Kerry in Washington, during Obama’s inaugural, that Caroline’s bid was “on track.” On Wednesday morning, Charles O’Byrne was telling the Kennedy camp that things looked good.

But now all was confusion.

When Caroline resurfaced, conference calls were hastily assembled. Over the next several hours, she debated what to do with a group that included Schlossberg; Isay; Nicole Seligman, her close friend since college, a corporate lawyer, and the wife of school chancellor Joel Klein; Gary Ginsberg, a close friend of her late brother, John, and a vice-president at News Corp.; and Ranny Cooper. Even in the midst of the confusing meltdown of her candidacy, with a supposedly serious personal issue suddenly looming, Kennedy, as always, remained impenetrably placid. “She’s not an emotive human being,” one friend says.

By 11 p.m., Kennedy had resolved to withdraw and called Paterson again. She hung up the phone newly perplexed: The governor, Kennedy said, insisted that she release a statement saying she’d changed her mind and was staying in the contest. “Paterson said, ‘You can’t withdraw, you gotta stay in this thing, and I’ll just not pick you,’ ” says one of her allies. “He seemed to think he was doing her a favor.” Not only would such a statement have made Kennedy look ridiculous, given the cascading media reports that she had already withdrawn, but it would have had the glaring weakness of being untrue.

A Paterson spokesman offers a diametrically opposed version of their last phone conversation. “At 11 p.m., she called back and apologized for being a recluse and told him she was definitely continuing with the race,” the spokesman says. “And we didn’t hear from her again until she put out a statement after midnight.”

Paterson awoke to the bad news and a shifting media wind: that even if Kennedy’s campaign had imploded on its own, Paterson had turned the selection process into a nightmare. Thursday quickly degenerated into open warfare between the governor and Kennedy. A Paterson spokesman claimed that the collapse of her campaign proved the wisdom of the governor’s decision to wait until Hillary Clinton had been confirmed as secretary of State before naming a replacement and that the vetting process had uncovered blemishes in Kennedy’s finances. The pushback soon went even further: Whether out of pure anger at her decision or a strategic need to shift blame, a “source close to Governor Paterson” trashed Kennedy, telling the Post’s Dicker that her personal problems were related to a nanny, unpaid taxes, and maybe even trouble in her marriage—and that the governor had “no intention” of picking Kennedy after her stumbling performance on the campaign trail.

Political operatives who have worked with him over the years say that the “source close to the governor” is often Paterson. An aide to the governor says he “seriously doubts” that Paterson was the source of the Post’s story. Regardless, Kennedy’s camp was furious. “We know there’s no vetting issue,” one of her allies says. “I know what’s in the disclosure form, and up through Wednesday at three o’clock, there had been no discussion of a vetting issue, no complaints from the governor’s counsel. And for him to include the idea of a marital issue is beneath contempt. There’s no marital issue!” Within hours, the governor’s office released a carefully worded statement disavowing the notion that his vetting process had anything to do with Kennedy’s withdrawing.

The next time Paterson was heard from publicly was in a press release declaring he was at last ready to end the whole Senate debacle: He would make his choice known to the world at noon on Friday. Paterson didn’t mention that he still hadn’t actually decided on the new senator. At 2 a.m. Friday, ten hours before he was scheduled to go public, Paterson sealed the deal with upstate congresswoman Kirsten Gillibrand and offered her the seat.

There were plenty of smiles as she was introduced in Albany last week, but Gillibrand is widely disliked within New York’s congressional delegation for her bullying personality and unwillingness to wait her turn in the Washington seniority queue. Already Congresswoman Carolyn McCarthy, of Long Island, has vowed to challenge Gillibrand in a 2010 Democratic primary because of the new senator’s pro-gun stance. Paterson seems to believe that he has cauterized the intramural Democratic fighting. Instead, the elevation of Gillibrand has widened the wound. Last Thursday, one of the governor’s aides called Andrew Cuomo, asking the attorney general to attend Gillibrand’s unveiling. Cuomo, according to a friend, said he’d be busy reorganizing his sock drawer.

Plenty of people still don’t buy any of the complicated, self-serving explanations and rationales. “No matter what anyone says, I’ll think she stepped down because she wasn’t going to get it,” one state Democrat says. After-the-fact claims by Paterson’s camp that he’d never had any intention of choosing Kennedy after her rocky start only made him look worse: If that were even remotely true, Paterson’s allowing Kennedy to remain in the race bordered on cruelty and set her up to be humiliated.

In all the rubble and recrimination, though, there is one thing the antagonists agree on: Paterson never said the magic words to Kennedy. He never literally offered her the job as senator. Was her camp criminally guilty of wishful thinking? Was Paterson right to keep everyone guessing until he was good and ready to decide? Did Kennedy’s self-destruction vindicate his extending the process as long as possible? No one is telling the whole truth, so the picture only gets murkier the closer you look.

Especially at the very center. After tens of thousands of words and uncountable hours of TV time devoted to her over the past eight weeks, Caroline Kennedy ends the most voluntarily public period of her life even more of a mystery than she was at the outset. So what are the “personal reasons” that caused the crisis? Kennedy wouldn’t say. “Is there a part of me that thinks she just got cold feet?” says one frustrated friend. “Sure. But I didn’t see any evidence of it.”

“Most politicians will do anything to be elected and to be in office,” one adviser says. “Caroline, because of who she is and the life she’s led and the sorrows she’s seen, sees life in a different way. Whatever the problem was, it was enough for her to say it’s not worth it. But I think it was something that a normal politician wouldn’t have let stop them.”

The first time Kennedy took control of her campaign was when she ended it. She was never able to integrate her dominant instinct for privacy with her newfound willingness to live in public. There is no more personal issue than trying to transform yourself into a new person. And now Caroline Kennedy, back out of sight, doesn’t need to endure the hassle of trying.