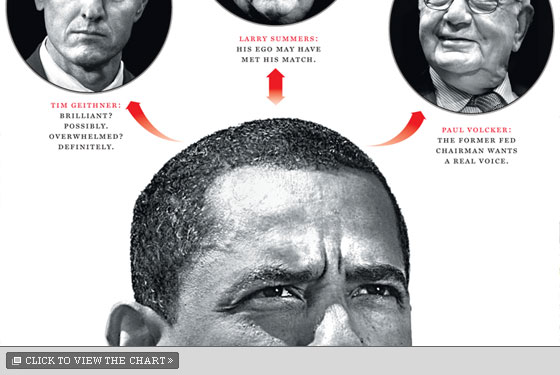

Tim Geithner boarded the 6 a.m. US Airways shuttle to Washington last Wednesday at La Guardia, slid his rail-thin frame into seat 5C, then stared into the middle distance. Geithner is invariably described as boyish, but that morning he looked every one of his 47 years—and then some. He wore a dapper blue suit, a spread-collar shirt, and dark circles under his eyes. For days, Geithner had been consumed in the unfolding AIG fiasco. He’d been running nonstop, laboring to contain the fallout, to explain how this bonus-related abomination had occurred, what he knew, when he knew it, why he seemed so impotent. But Geithner was too smart to harbor any illusions about the efficacy of those efforts. He knew that what awaited him in Washington was going to be ugly. When the plane touched down, he gathered his things and walked silently toward the jetway. He had the look of a man about to enter a burning building in a suit soaked with gasoline.

What greeted Geithner in the capital was a full-blown firestorm. Republicans were howling and screeching, calling for his head on a pike. Some Democrats privately agreed. On Wall Street, meanwhile, where Geithner’s stock has been falling precipitously for weeks, a prominent Democratic banker (and Obama backer) told me, “It’s not that everyone here thinks he should be fired. It’s just that there’s no one who would stand up right now and publicly throw their support behind him.”

Geithner’s survival appeared to be hanging by a thread. Even before the AIG maelstrom, a certain slow-drip sense of disillusionment had been setting in about his up-to-the-jobness among certain White House officials. The tax thing. The terrible speech. The lack of confidence in the financial markets. And yet, for the time being at least, Geithner retained the support of the only White House constituency that matters—the constituency known among old executive-branch hands as the constituency of one. Which is to say, Barack Obama.

“Tim Geithner didn’t draft these contracts with AIG,” Obama said, adding that Geithner has his “complete confidence.” “Nobody’s working harder than this guy. You know, he is making all the right moves in terms of playing a bad hand.”

That Obama would defend Geithner on AIG comes as no great shock. According to the president’s chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, Obama regards the bonus imbroglio as a “distraction” from more urgent economic priorities; his goal is to move past it and allow Geithner to get back to the business of rescuing the financial system. Yet AIG will not be so easily brushed aside, for it has brought to a boil the simmering doubts about not just Geithner but also his partner Larry Summers, director of Obama’s National Economic Council, and the economic approach they are fashioning and advancing for the administration.

When Obama appointed Geithner and Summers back in November, the reaction in Washington and on Wall Street was the same: first relief and then elation. (The day the news of Geithner’s selection leaked, the Dow rose 6.5 percent.) They were brilliant, experienced, crisis-tested, market-minded but progressive, a kind of economic-policy dream team. Since then, they have worked side by side along with Fed chair Ben Bernanke to quell an economic crisis as monstrous as any since the Great Depression—while formulating an economic agenda as ambitious as any since FDR’s. They’ve unveiled big plans, talked big talk, and crafted and shepherded into law the biggest fiscal-stimulus package in American history.

But Obamanomics represents something even bigger than all that. At a moment when the fundamental precepts of market capitalism and government’s relationship to the economy are up for grabs, the Obamans are attempting nothing less than a redefinition of progressivism, which could alter the terms of political engagement and the ideological balance of power for decades to come. With their budget, they have laid out a vision that, as former Labor secretary Robert Reich puts it, “reverses and repudiates the economic philosophy that has dominated America since 1981.” Obamanomics isn’t merely the end of Reaganomics, in other words. It’s the end of Rubinomics, too.

An agenda this transformative is bound to stir up criticism, and so it has—from the left and the right, Wall Street and Main Street, arch-Establishmentarians and hot-eyed populists in roughly equal measure. The complaints of these factions vary wildly, but they share a point of agreement: that the administration so far has badly mishandled the banking crisis; that it’s dithered, dawdled, and dinked around instead of delivering bold, decisive action. For Obama, confronting this issue poses a vexing dilemma. Saving the banks is the sine qua non for the country’s emergence from its ever-deepening miasma, but in doing so, Obama risks incurring a tsunami of bailout rage. If, on the other hand, he appeals too much to populism, he risks driving elites away. Either outcome could deny him the support he needs for the rest of his agenda. Getting the economics right may be devilishly difficult—but the politics are even trickier, and just as crucial.

By the time you read this, in all likelihood, Geithner will finally have unveiled his plan, developed with Summers, for rescuing the banks. The stakes could not be higher. To no small extent, Obama is betting his presidency on their ability to help him pull this off. Their skills, brains, and dedication are not in question; for all the brickbats being hurled their way, they are laboring tirelessly, even heroically, against a nightmare not of their making. The question is, will that be enough?

Not quite a year ago, Summers and I were chatting in the lounge of the Harvard Club in midtown, where he’d come to deliver a lunchtime speech on the state of the economy. The race for the Democratic nomination was still under way but Obama’s victory was likely and Summers (who, unlike most of the veterans of Bill Clinton’s administration, in which he rose to become Treasury secretary, stayed neutral rather than siding with Hillary) began musing about the presumptive nominee, whom he knew only in passing. “When I’ve heard him talk about economic issues—with the exception of NAFTA, where I just hope he doesn’t believe what he says—he seems intelligent and serious,” Summers told me. “I wouldn’t say I’m bowled over by the brilliance of anything I’ve heard, but everything has a kind of thoughtfulness to it that’s sort of impressive.”

Throughout his career—from becoming, at 28, one of the youngest tenured professors in Harvard’s history to his brief and inglorious tenure as the university’s president—much has been made of Summers’s abrasiveness and regard for his own candlepower. “Larry Summers is to humility what Madonna is to chastity,” The Wall Street Journal editorial-page editor Paul Gigot once wrote. But unlike most intellectual bulldozers, Summers enjoys people who fight back, even invites them to. He also has a fine sense of humor about himself. After reading Gigot’s gibe, Summers told his then-wife, “Well, it’s not as bad as it could have been: He could have said that I’m to chastity what Madonna is to humility.”

Even so, Summers tends to thrive around those who possess, shall we say, a healthy ego—which helps explain why he and Obama clicked from the start. Summers made his way into the campaign via Jason Furman, a former underling of his at Treasury who became Obama’s lead economic adviser. When the financial crisis hit in September, Furman put Summers in charge of doing the opening presentation on Obama’s economic conference calls, which took place daily (at least) during that pivotal time. “Larry was just brilliant on those calls,” recalls one regular participant. “And not just brilliant but inclusive and generous—he was very rarely as assholic as he had a reputation for being.”

After Election Day, Obama rapidly narrowed his options for Treasury to Summers and Geithner. Summers badly wanted the job; Geithner offered to stay in his post as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. But the controversies that Summers aroused at Harvard with his impolitic, incendiary comments regarding the underrepresentation of women in the sciences made his confirmation seem riskier. Obama also heard from many Summers opponents. “The problem was, 50 percent of the people Obama asked about Summers said no fucking way—between the confirmation hurdles and the arrogance problem,” says this person, who was asked. “But everyone said he had to have Larry at the table. And Obama had really come to respect him. The funny thing is, Barack barely knew Tim; they’d only met a couple times, there was no relationship there.”

But Geithner, who’d grown up in Southeast Asia, been a Summers protégé at Treasury, done a stint at the IMF, and become president of the New York Fed in 2003, had a sterling résumé and a reputation as a consensus-builder that appealed to Obama. His firsthand experience working with Hank Paulson during the tumult of last fall—the collapse of Lehman, the rescue of AIG, etc.—struck Obama as an asset, not a deficit. And so did his cool, detached, ironic style, which mirrored that of the president-elect.

The decision would prove fateful. Whatever difficulties Summers might have encountered during the confirmation process, it’s hard to believe they would have been more acute—or lastingly debilitating—than the controversy that arose over Geithner’s taxes. To start with, Tom Daschle would likely have been able to survive his own l’affaire IRS. And perhaps more consequentially, the tax-compliance flyspecking that has made filling the senior posts under Geithner so difficult might have been avoided.

Summers got over his initial disappointment, consoling himself with the idea that proximity to Obama would enhance his influence and running the National Economic Council would give him wider latitude to range across almost every aspect of domestic policy, from health care to energy. The first major initiative on which he left his imprint was, however, strictly economic: the stimulus package. In meetings last summer with CEOs and financial types, Obama had debated whether he’d be able to push the envelope and propose a $100 billion stimulus past. By November, though, the economy was in free fall, and the mooted price tag of the bill had risen to $500 billion. But Summers decided that the number should be higher and, at a meeting in mid-December, persuaded his colleagues—some dubious that such a massive bill was necessary, others fearing that it would never get through Congress—to push for a $775 billion package.

In the wrangling over the bill on Capitol Hill this winter, the role that Summers played—shimmying it through the House, tweaking it to make it more acceptable to the Senate—was pivotal. The end product drew criticism from the left and right, but in size ($787 billion) and broad outline, the bill was close to what Obama originally put forward. “People can quibble on the details,” says Austan Goolsbee, a member of the Council of Economic Advisers. “Republicans say that it should have had even more tax cuts. Others say that it should have had more infrastructure spending. But what’s not under dispute is that in the first four weeks of the presidency, we passed the biggest stimulus package in American history.” End of story.

The passage of the stimulus package was, no doubt, a significant victory for Obama, Summers, and the rest of the economic team. But for Geithner, the triumph coincided with the start of what would be for him a long and brutal stretch. For on the same day that the Senate passed its version of the stimulus, thus essentially guaranteeing its enactment, Geithner delivered his maiden speech on the Obama plan to save the banks.

Until that moment, the praise for Geithner—from his colleagues, bankers who’d been regulated by him, and other denizens of the financial world—had been extravagant. Genius was a word frequently employed. So was superstar. “I went through battle after battle with Tim, and he’s quite remarkable,” says a former Treasury official from the Paulson era. “He’s a very strong leader. He’s smart, he’s tenacious, he works harder than anyone. There were countless times when Paulson and Ben Bernanke were focused on academic discussions and Tim was the one who brought things back to reality.”

Yet even as Obama was weighing giving Treasury to Geithner, some skeptical voices were heard, especially among players in the financial markets who believed that, in a time of crisis, a grayer head of hair was warranted. (Some suggested putting former Fed chairman Paul Volcker in the job for a year, with Geithner as his deputy and successor in waiting.) “I have great respect for Tim,” says one of them. “But I thought he lacked the gravitas for the job, the ability to be a commanding figure, to get on TV and have people take one look at him and say, ‘Yeah, he’s the man.’ ”

Not even the most ardent Geithner skeptics could have predicted the disaster that was his February 10 speech, however. Speaking slowly, as if he were on a mild sedative, swaying side to side, his eyes darting from left to right as he labored to read from the teleprompters flanking the podium, Geithner gave a performance positively McCainesque in its degree of maladroitness. And that may have been, lordy, lordy, the least bad thing about it. The night before, at his own press conference, Obama had said that Geithner would “be announcing some very clear and specific plans for how we are going to start loosening up credit once again.” And: “I don’t want to preempt my secretary of the Treasury; he’s going to be laying out these principles in great detail tomorrow.” And: “I’m trying to avoid preempting my secretary of the Treasury, I want all of you to show up at his press conference as well; he’s going to be terrific.”

But Geithner offered precious little that was specific and provided few details. Obama’s raising of expectations would have been ill-advised under any circumstances. But these were not just any circumstances. “Tim and Barack might have been able to get away with ‘Trust me on the details’—except that they were following Paulson, who asked to be trusted so many times and then changed directions that no one was going to trust any Treasury secretary on the details,” remarks a senior executive at one of Wall Street’s biggest banks. “And then here comes Tim and says, ‘Trust me on the details.’ Oy vey.”

What had happened was that Geithner, after weeks of working on the plan, changed his mind late in the game and decided to pursue a different path. Without time to craft fully the new strategy, he concluded that vagueness was preferable to providing details that might have to be altered later. One problem, though: Apparently no one told Obama.

The torrent of abuse that rained down on Geithner was withering and ceaseless. In something like a heartbeat, he became in the eyes of the financial community—which, for all its lunacy, stupidity, avarice, and culpability in the current financial implosion, remains for any Treasury secretary a constituency of paramount importance—something between a bad joke and a calamity. The situation was exacerbated by the paucity of senior staff at Treasury, which has made it nearly impossible for Wall Street to talk to Geithner’s shop: “There is no one there to answer the phone,” says one executive. “Literally.”

To some in the White House, the sight of the financial world turning hard against Geithner is curious, even baffling. What the Obamans thought they were getting in him was Wall Street’s guy. “They don’t get it,” says one name-brand Democratic banker. “Geithner was a $500,000-a-year guy. He was the regulator. People knew him, liked him fine, but he was never a member of the club.”

A longtime Geithner ally in Washington comes to a different conclusion. “A lot of the pushback he’s getting from Wall Street is about their lack of self-awareness about how the world has changed, how they’re not the Masters of the Universe anymore,” this person argues. “They feel marginalized and put-upon by the administration’s rhetoric about the greedy bankers. They are way behind the curve about where the public is and how much pressure the administration is feeling. They don’t like what the new environment means for how they run their business. They see their taxes going up and their compensation going down. And what they don’t do is go to the New York Times and say, ‘My feelings are hurt. I don’t like what the new president is saying about our character and our competence.’ What they say is, ‘These guys are incompetent, we need a real policy, the Treasury secretary has got an unsteady hand—he’s not up to the job.’ They’re thinking one thing and saying something quite different.”

There may be more than a smidgen of truth in all of that. Yet what’s equally true is that the private-sector worries about the plans being cooked up by Geithner and Summers extend into countless corporate suites, start-ups, and small businesses far beyond Wall Street—and that until recently, the administration was comically clueless about it. When I was at the White House recently, I jokingly asked a senior Obama official if the team was having fun turning the country into a socialist state. “What are you talking about?” this official replied. “Business loves what we’re doing!”

Back in New York the following day, I related that story to a CEO pal of mine who is a big Obama backer. “What are they, smoking crack down there?” he replied. “Find me one CEO who likes what they’re doing. Seriously, find me one!”

It’s fair to point out that a lot of CEOs are, you know, Republicans. But even the Democrats among them tend to be queasy about the Obama agenda. Their qualms revolve around both the stimulus and the budget. Among those in the fiscal-rectitude crowd, the argument is that Summers failed to deliver on his pledge that the package would be “timely, targeted, and temporary”—that it ended up being both too poky and too porky. (Only $185 billion, after all, will be spent within the next year.) But others chime in on the side of the many economists who contend that, given the likely shortfall in output this year, $787 billion, though a mighty big number, ain’t gonna be big enough. This is not just lefties talking, by the way: Forty-three percent of the dismal scientists surveyed recently by The Wall Street Journal said that another $500 billion package will be required.

If the stimulus provokes concern in the private sector, the budget causes nothing short of a total freak-out. The size of it ($3.6 trillion in fiscal year 2010) and the oceans of red ink it threatens to unleash give deficit hawks the heebie-jeebies. The redistributionist tilt it brings to the tax code wigs out the wealthy, the modestly wealthy, and the wannabe wealthy. The oxen it gores (e.g., agricultural subsidies) offend entrenched industrial wards of the state.

Beyond those particulars, the sheer ambition and audacity of the thing—health-care reform, cap-and-trade, and much more—raises suspicions that the Obamans are attempting to capitalize on the crisis instead of solving it. That they’re taking on too much too fast and winding up, as Obama backer Warren Buffett put it, with “muddled messages.” That they’re diverting their energies, failing to put all their wood behind the arrowhead that should be aimed at one challenge that counts above all and before everything: fixing the financial system. “I heard [Obama budget director] Peter Orszag on TV saying health care is the biggest problem affecting the economy,” says one Democratic CEO. “No, it’s not. Right now, of the top ten things they should be focused on, it’s like, No. 11; the first ten are the banks.”

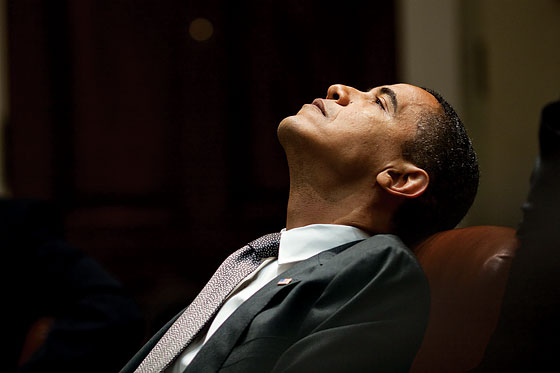

Obama has a reasonable answer to this charge. “There are some who’ve argued that we can’t do all these things at once and that we should instead just focus on Wall Street and banking,” he told a group of reporters recently. “I think that would be a mistake. I think that extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures. So even as we’re working on financial stabilization, reregulating Wall Street, we’re going to keep on pressing to get the investments that will ultimately lead to long-term economic growth.”

Obama has made this argument on several occasions now, but it made its debut when he addressed the Business Roundtable earlier this month. It was one of those occasions where the venue for the message mattered nearly as much as the message itself. “What it said to me was, they know they have a problem with business, that they’re not in la-la land about that any more,” explained another Obama-friendly executive in the city. “But unless they fix the banks, nothing else matters. That’s what everyone is waiting for.”

Paul Volcker, you might think, would have some helpful ideas on that topic. On March 13, Volcker met Obama in the Roosevelt Room of the White House. Accompanying him were a half-dozen of Obama’s closest private-sector confidants, all members of the Economic Recovery Advisory Board that the president unveiled in February and that Volcker chairs. There was former SEC chairman William Donaldson, TIAA-CREF CEO Roger Ferguson, private-equity hotshot Mark Gallogly, hotel magnate Penny Pritzker, Yale CIO David Swensen, and UBS Group Americas CEO Robert Wolf.

Afterward, Obama would describe the meeting, with pristine vagueness, as being a discussion of “a wide range of issues, but with some particular focus on the financial markets.” In fact, the conversation revolved almost exclusively around the banks: how to get the toxic assets off their books and whether solving the financial crisis might require nationalizing some of them. Some were pro-nationalization; most were not. But Obama questioned all of them closely on the matter, pressing them for scenarios of what might unfold if the government went that far.

For Obama, the substance of the meeting may have been less important than the optics of it. In the worlds of finance and business, few figures are held in higher esteem than the towering, stoop-shouldered, marble-mouthed Volcker. So it has hardly gone unnoticed that he has lately seemed, ahem, less than thrilled with Team Obama. He has privately complained that Summers has frozen him out of the policy-making process. He has publicly criticized the sluglike pace of filling top jobs at Treasury as “shameful.” With the White House meeting, Obama had a chance to make Volcker happy—and in the process use him as a piece of photo-op arm candy, sending the message that the chairman remains standing, literally and figuratively, beside him.

Was Volcker placated? Maybe only momentarily. “He wants to have a real role,” says someone who knows him. “If they’re gonna call him an Obama adviser, he wants to really advise. He has no interest in just being window dressing.”

But Obama will need all the window dressing he can get if the administration’s bank-rescue plan is going to work. Though the details had yet to be announced as of this writing, the outlines of the plan seemed pretty clear. First, the government would create public-private partnerships, in which a handful of hedge funds and private-equity groups, backed with taxpayer dollars and guaranteed against big losses, would buy up the toxic assets from the banks. Once the banks’ balance sheets were cleaned up, the government would inject the necessary capital into those banks to keep them solvent until private investors stepped in to fund the newly healthy banks. At the same time, the government is administering the so-called stress tests to determine which of the nineteen biggest banks are dangerously undercapitalized and will require injections of government dough (in exchange for preferred stock) to stay afloat if the economy worsens.

Even (or especially) absent details, nobody has the faintest clue whether the plan will work. But everyone believes that, even if it does, the cost will be stratospherically high—likely upwards of $1 trillion, comprised of the $250 billion still in the kitty from Paulson’s original tarp program plus the $750 billion that the Obama budget warned Congress might be needed. The problem, politically speaking, is that the public appetite for ponying up for further bailouts is small and shrinking by the day, thanks in no small part to the depredations undertaken by AIG.

Considering all this, it might seem strange that Obama’s economic and political gurus seem to be straining mightily to avoid nationalization. The political rationale for the idea is obvious and potent. (I refer you to Paul Krugman et al. for the economic rationale—which is way above my pay grade.) The only way that the electorate is going to sign on to the level of spending necessary to keep the financial system from imploding is if there is some tangible upside for the taxpayer—as opposed to the current bailout paradigm, which Krugman refers to as “lemon socialism: Banks get the upside, but taxpayers bear the risks.”

There are those who believe that the administration grasps the point perfectly well. That nationalization is where it’s headed, slowly but surely. That the stress tests are really just a backdoor way into temporary government ownership of the current zombie banks—a means of providing a sense of order, consistency, and due process necessary to make nationalization seem an empirically based act of last resort.

Obama’s economic advisers wave off such talk. They dismiss Krugman and other pro-nationalizers as engaging in mere punditry, of failing to grasp the mind-boggling practical complexity of nationalizing a bank such as Citi, with its 350,000 employees in more than a hundred countries around the world. Geithner is said to be averse to the idea—though some think Summers may be somewhat more open to it. Last July, in his former Financial Times column, Summers argued that the government should put Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into receivership, “conserving cash for the benefit of taxpayers.” “All I can tell you,” says one administration official, “is that Larry seems quite happy with this part of the policy portfolio being known as the Geithner Plan.”

The truth, in the end, is that whatever emerges will be perceived as the Obama plan. And the president is apparently deeply uncomfortable with nationalization. “Barack’s perspective is, if you do one bank, what happens to the next weaker one and the next one and the next one?” explains someone with his ear on economics. “Where do you draw the line? How far do you end up going? What are the repercussions?” Obama, notes this person, is risk-averse in his decision-making. “He wants to know in advance the likely outcome. So he’s saying to Tim and Larry, let’s play it out—and there is no solid answer. If you do Citi, you can’t be sure what that means for B of A. You’re not sure whether Goldman and Morgan can survive as just investment banks. That level of uncertainty is something that, for them, is really hard to swallow.”

When Obama picked Geithner and Summers as his top two econo-poobahs, the main knock against them came from the left: They were both protégés of Bob Rubin. And, to an extent, it was true. Both had worked under Rubin in the Clinton administration. Both considered him a close friend, a mentor, a rabbi. Both had advocated the core policy positions that defined Rubin’s time in government under Bill Clinton: free markets, free trade, globalization, deregulation, fiscal discipline = good; big deficits, protectionism, xenophobia, class warfare = bad. In this sense, they were proponents of what became known as Rubinomics.

Two months into the Obama era, however, it’s hard to detect many traces of the Rubin doctrine in what the new president and his people have done or are planning to do in the future. The administration proposes to run a $1.17 trillion deficit in 2010. It intends to reregulate the financial industry. The reduction of income inequality is at the core of its tax and spending proposals. Its budget plan reflects “the largest commitment [to public investment] in 40 years,” notes Bob Reich. And it imagines a level of direct government involvement in the market (and particularly in the banking sector, nationalization or no) that would have Rubin spinning in his grave—if he weren’t still kicking, that is.

With an agenda like this, it might be tempting for Obama to tilt toward a full-throated kind of left-leaning populism—especially at moment when populist ire in all its incarnations is plainly in the ascendancy. Some of Obama’s political people, including his senior adviser, David Axelrod, certainly have inclinations in this direction, and are plainly worried that the populist ascendancy might threaten to derail his agenda unless he co-opts it. But honest-to-Betsy populism neither suits Obama temperamentally nor would serve his interests. In a time of profound economic paroxysm, Obama needs the private sector on his side. He needs its energies, its productive capacities, its ideas, its support. Government can help prevent the economy from spiraling down the drain, but only the engines of commerce and entrepreneurship can power it to full and lasting recovery.

The balancing act that Obama must therefore pull off is a hell of a party trick. He must court the elites without pissing off the masses and soothe and provide catharsis for the masses without alienating the elites. His political advisers, seeing his poll numbers beginning to slip, are applying their war paint and preparing to do what they do best: pick a fight with the Republicans. (Rush Limbaugh, anyone?) But however tempting this might be, Obama would do well to rein them in. Not because there’s any inherent virtue in bi-partisanship or kowtowing to Republicans. But because picking fights during a national crisis looks small, unserious, and faintly oblivious to the severity and significance of what’s occurring around us.

This is not, in short, an us-versus-them moment. It could be, should be, an all-hands-on-deck moment. Obama, I suspect, understands this better than most of the people around him. Late in his campaign, Obama gave a speech in Indianapolis in which he unfurled a kind of optimistic, soft populism that was both eloquent and perfectly calibrated for the times.

“We will all need to sacrifice, and we will all need to pull our weight, because now more than ever, we are all in this together,” Obama said. “What this crisis has taught us is that at the end of the day, there is no real separation between Wall Street and Main Street. There is only the road we’re traveling on as Americans, and we will rise and fall on that as one nation, as one people.”

He should say that again. Not just because it’s a great set of lines—but because, like all the best rhetoric, it also happens to be true.

On Tim Geithner:

“It’s not that everyone here thinks he should be fired. It’s just that there’s no one who would stand up right now and support him.”

On Larry Summers:

“All I can tell you is that Larry seems quite happy with [the banking proposal] being known as the Geithner Plan.”

On Paul Volcker:

“Has no interest in just being window dressing.”