The shuttle that transports senators from the Capitol to their offices shimmies a bit, like a kiddie roller coaster. Kirsten Gillibrand, new to the ride, holds on to her seat very tightly as the train clatters to a stop. Gillibrand is already into hour six of her day, and it’s barely noon. She drove her 1-year-old son, Henry, to day care, clutching a bottle of breast milk she had pumped earlier. She then banged out “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” on a Fisher-Price keyboard. Henry didn’t want her to go (“It’s okay, Bunny, I’ll see you tonight”). There was a short drive to a breakfast held by the gay lobbyist group the Human Rights Campaign (“Who wrote these remarks? They’re not very good”), then a series of discourses on the special bond she feels with gay people (“I was a 34-year-old woman lawyer working twelve hours a day in New York City. All the men in the firm were married. My only friends were gay men”), why door-to-door campaigning is easy for her (“I was the No. 1 Girl Scout–cookie seller as a girl! I’d go into any neighborhood!”), and what she thought of Maureen Dowd’s labeling her Tracy Flick and calling her sharp-elbowed (“I think I have nice elbows”). We get off the train, and Gillibrand strides ahead in sensible black flats (“You would never write about Chuck Schumer’s shoes, but it’s okay. People want to know these things”).

Kirsten Gillibrand is working hard to reintroduce herself to her constituents. Her first hundred days were marred by policy flip-flops, threats from political rivals, and images of her as a fighter for Big Tobacco who happened to keep two guns under her bed. So she is giving it another go. “My parents and my husband have been worried about the coverage,” says Gillibrand. “I told them, ‘Give me six months, and I will make it better.’ People meet me, they like me. I work hard.”

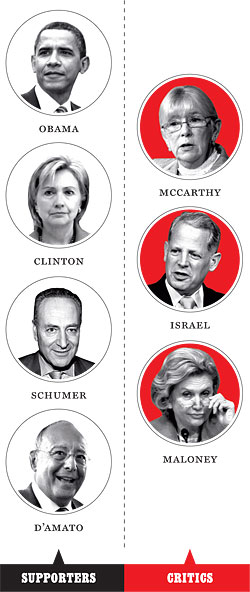

New York is not a particularly civil town, especially when it comes to politics. And Gillibrand started dodging insults even before she was sworn in. Her former colleague in the New York congressional delegation Carolyn McCarthy called her appointment “totally unacceptable.” Another New York representative described her selection as “mind-numbing.” And yet many of the traits that Gillibrand’s foes use to attack her are the same traits that make her likely to hold her Senate seat in 2010. Sure, she is pushy, in a Tracy Flick sort of way. Yes, she has shown all the ideological purity of the McCain campaign. And absolutely, she is cozy with Republicans—Al D’Amato stood next to her at her appointment-announcement press conference.

But while everyone was mocking and plotting, Gillibrand raised $2.3 million in less than 90 days during an economic meltdown. She’s got the Clintons on her side. Chuck Schumer has embraced her. She has received the support of the twelve other Democratic women senators. Last month, President Obama made a call and talked potential Democratic primary opponent Steve Israel out of challenging her. Even Caroline Kennedy’s cousin, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has been kind to her in public.

Gillibrand is a fan of J.R.R. Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” books, and her life has had a similar the-quest-is-all momentum. She is practical and not inclined toward introspection, helpful qualities when you are trying to morph from an upstate congressional representative who supported building a bigger fence along the Mexican border and achieved a 100 percent NRA rating to a United States senator in need of statewide votes who is now an immigration advocate who decried gun violence the week of the mass shooting in Binghamton. Gillibrand is the scion of a local political family determined to make the last difficult leap from the merely well connected to the power elite, and she appears to be succeeding.

I heard a common refrain from her colleagues. They see Gillibrand as a young woman in a hurry whose aggressiveness seems almost gauche, even for a politician. Yet her upstate roots and young children give her an Everymom image that middle-class voters love. And her drive has its benefits. “She is working or thinking about things she needs to do every moment that she is awake,” says Elaine Bartley, her longtime best friend. “The rest of her friends, we’re trying to get thank-you notes out a month after our kid’s birthday party, and she’s getting them out the next day.”

Her lack of polish can cause opponents to dismiss her as a country bumpkin who is in over her head. But her folksiness comes with a sharp edge. She learned how to play hardball from her grandmother, a legendary political force in Albany. She has the work ethic of someone who spent tens of thousands of hours of her youth on mind-numbing legal work. And she is a canny collector of political friends. “She has a single-mindedness about where she wants to go,” says a Democratic activist who knows her well. “She wouldn’t throw her mother under a train, but she’d run you over with a train if you got in her way.”

Gillibrand is preppy, blonde, short, and athletic. She looks like someone who might give tennis lessons at a country club, as she did when she was 16. She has run two marathons but is sensitive about the baby weight she has yet to shed. Her children have been sick recently—there was a trip to the emergency room last week—but she powers on, even boasting about her endurance. “I get up with the kids when they’re sick. Johnny, my husband, doesn’t do as well with interrupted sleep as I do.”

We’re in her office now. Gillibrand has moved into Hillary Clinton’s old space, but because of a bureaucratic delay, she’s not fully unpacked. The walls are bare and smell of fresh paint. When I ask Gillibrand what politicians have inspired her, she pauses a moment, then cites her grandmother.

If you make a quick right off the New York State Thruway onto a service road on the outskirts of Albany, you’ll come to Noonan Lane. The oldest home on the secluded street was once the residence of businessman Peter Noonan and his wife, Polly, Gillibrand’s maternal grandparents (the street was named after their family). Less than a mile away is Corning Hill Road, the longtime home of Erastus Corning II, Albany’s “mayor for life” from 1942 to 1983. Polly met Corning in 1937 while working as a secretary for the Scenic Hudson Commission, an organization helmed by Corning, then a state senator. Their friendship confounded and fascinated Albany for nearly half a century.

The mayor was a prep-school Wasp who shipped his own two children off to boarding school; Noonan was the lightly educated daughter of Irish immigrants. Her salty manner is said to have loosened up the buttoned-down Corning, and she exercised power as a patronage queen during his reign. The mayor’s own wife avoided political functions, so Noonan served as Corning’s traveling companion. According to Paul Grondahl’s biography, Mayor Corning, Noonan once entertained two journalists on a flight back from the 1974 state Democratic convention with cracks about Corning’s failing sexual prowess. Grondahl writes that there is no evidence that Albany’s political odd couple was ever sexually involved, but the relationship was certainly close. Corning spent so many evenings at the Noonans that he had his own recliner, just across from Peter’s.

Although Corning was estranged from his own children, he treated the Noonans’ four children as his own, particularly Penny Noonan, Gillibrand’s mother. When Penny started dating a boy named Douglas Rutnik, Corning informally adopted him too. Penny Noonan and Doug Rutnik eventually married, went to law school, and started Rutnik and Rutnik, an Albany law firm that benefited from municipal business Corning steered its way. When Corning died, in 1983, he left his family’s insurance practice to the Noonan children.

Polly Noonan liked to keep her family close, so Penny and Doug Rutnik built their own house on Noonan Lane. (Two of Polly’s other children eventually built houses on the block as well.) Kirsten Rutnik was born in 1966. She is the couple’s middle child, sandwiched between an older brother, Doug, and a younger sister, Erin.

Gillibrand talks often about helping her grandmother do political work as a child. “We’d do typical stuff like putting bumper stickers on cars,” she says. She flashes a mischievous look. “Sometimes, you are putting your own candidate’s bumper sticker over somebody else’s candidate’s bumper sticker.”

It’s not hard to see where Gillibrand gets her confidence. “Penny was the first real working mom that a lot of us kids knew,” says Elaine Bartley. “She was always multitasking, working on a case on the phone while unloading the dishwasher. That’s where Kirsten got the idea that she could work, raise kids, do it all.” Now semi-retired, Rutnik spends much of her time in Florida or with her grandchildren. She’s also a hunter who shoots the family turkey every Thanksgiving. “We never pushed Kirsten into politics. She took to it naturally,” Rutnik told me not long after Gillibrand’s Senate appointment. “I thought the governor would be crazy not to choose Kirsten. Then Caroline Kennedy came along, and I wondered why anyone would take her seriously. It annoyed me: Just because she’s a Kennedy, people think she can do the job. And then I heard Caroline speak, and it was clear this was not her forte. That’s when I knew Kirsten had a chance.”

Gillibrand attended Catholic grade school in Albany and went to high school as a day student at the prestigious Emma Willard School, in Troy. She spent most of her time studying, she says. “I was a big nerd. I wasn’t the smartest, but I’d put in tons of hours.” On the school’s tennis team, Gillibrand earned a reputation as a player who wore down her competitors by returning their shots until they crumpled with exhaustion. Because her parents lived nearby, Gillibrand often hosted classmates from Emma Willard for sleepovers. “Kirsten was always working out deals and compromises, even then,” says Bartley. “She’s always been very social, very outspoken. She was always the central character in any event while we were growing up.”

Gillibrand debated between Princeton and Dartmouth for college. “I went to visit Princeton, and all the girls wore a ton of makeup and high heels and had fancy pocketbooks,” she says. “And then I visited Dartmouth, and everyone was in sweats with no makeup, doing outdoor things. That was more my speed.” At Dartmouth, Gillibrand majored in Asian studies after taking a class in Chinese politics. “Learning Chinese doesn’t have a lot to do with talent or skill,” Gillibrand says. “It is about putting in the hours doing rote memorization. And I knew I was good at that.” She joined a sorority and played tennis and squash, but didn’t participate in student government. “I didn’t like the type of people involved,” she says. But her fellow students nevertheless saw where she was headed. “She was always very nice. She always remembered names,” says a classmate. “You could see how she could become a politician.”

Gillibrand was viewed by some as a career climber as early as law school. She enrolled at UCLA in 1988, and spent the summer between her first and second year interning in the Albany office of then-Senator Al D’Amato. Gillibrand’s father had become close with D’Amato in the eighties, serving as a conduit to the capital’s political Establishment (after Rutnik and Penny Noonan had divorced, Rutnik dated Zenia Mucha, a senior D’Amato aide). Gillibrand passed the bar in 1991 and moved to Manhattan to take a job as an associate at the law firm of Davis Polk & Wardwell. The next year, she received a prestigious clerkship with Court of Appeals judge Roger Miner, a Republican appointee. Because the position was so coveted, and Gillibrand had not finished in the top 10 percent of her law class, it was assumed that she received the position based on her father’s D’Amato connections.

After her clerkship, Gillibrand returned to Davis Polk, where she worked for nine years, logging long workweeks for a series of clients including the tobacco conglomerate Philip Morris. During her 2008 congressional reelection, operatives for Sandy Treadwell, her Republican opponent, compiled boxes of information that documented Gillibrand’s involvement with Philip Morris, but the media was largely uninterested. The New York Times revisited the material after Gillibrand’s Senate appointment. The Times’ 2,700-word front-page story depicted Gillibrand as a key player on the account, making trips to Philip Morris’s European cigarette-testing lab and using her office as a war room to plot strategy to defend the company against government claims that it knew tobacco was a carcinogen and hid that information from consumers. The story noted that Davis Polk allowed associates to decline to work for certain clients if they found the work ethically objectionable, but that Gillibrand appeared to have thrown herself wholeheartedly into her Philip Morris assignment.

Gillibrand declined to speak to the Times for the story, but when I asked her if she regretted her work, she answered with a defiant “No.” She didn’t defend the work on its own terms, however. “I had an opportunity to work with Robert Fiske on the case, and he is universally regarded as one of the great lawyers of our time,” she told me. Then she said, “And the work on that case allowed me to do pro bono cases.” Gillibrand then listed some of the pro bono cases she worked on—helping battered women get divorces from abusive men and aiding a housing alliance to sue landlords over lead-paint problems—but as with most lawyers, the pro bono work took up no more than a fraction of her time.

Gillibrand began attending fund-raisers for the Clinton-Gore reelection campaign and building a database of political contacts. “Kirsten has been compiling lists and contacts since Dartmouth,” says Sarah Hoit, a college friend who served in the Clinton administration. “She saw the benefit of e-mail lists long before others did.” Penny Noonan Rutnik recalls that her daughter was already thinking about her political career when she was at Davis Polk. “I remember getting a call from her saying she was having a tough time finding a cleaning woman who wanted to be paid legally,” Rutnik says. “I said, ‘What’s the big deal?’ And she said, ‘Mom, I might want to run for office someday. I can’t have an illegal cleaning my house. I’ll do it myself if I have to.’ ”

Gillibrand says it was Bible study that awakened her to public service. “When I was working in New York, I taught a Bible class for 10-year-olds,” she says. “My favorite parable is the one Jesus tells about the talents.” She’s referring to the story in which a master becomes angry with a servant for wasting a coin, or “talent,” he was given. “What I took from that is we have to do the most with the talents God has given us. I was working as a corporate lawyer, where I wasn’t helping people. I was just helping big companies make money. And I wanted to do more.” The story may be true, but it clearly sounded rehearsed.

Gillibrand’s first foray into public service came in 2000, when she ran into then–HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo at a fund-raiser. She simply approached Cuomo, she says, and explained her desire to get into public service. A representative from Cuomo’s office called her the next day and offered her a job as a special counsel. “I said, ‘Can I think about it?’ ” Gillibrand says. “He said they needed to know by the end of the day. I said yes.”

After George Bush defeated Al Gore that November, however, Gillibrand returned to corporate law, becoming a $500,000-a-year partner at Boies, Schiller & Flexner, working with star Democratic litigator David Boies. She also began raising money for New York Democratic heavyweights like Hillary Clinton and Eliot Spitzer. Gillibrand met Clinton in 1996, and, as she tells it, the pair bonded over their shared experiences as women in the male-dominated world of corporate law. They spoke regularly, if informally, over the next several years, and when Clinton decided to run for Senate in 1999, Gillibrand joined the fund-raising group Women for Hillary.

In 2002, Gillibrand informed Boies, Schiller that she was thinking about running for office. The firm allowed her to transfer from New York to its Albany office, and she established residency in nearby Hudson. “When I was living in New York, I thought about running for City Council or State Assembly, but there were twenty qualified candidates for every opening,” Gillibrand says. “So I thought, ‘I like federal issues. What about Congress?’ I asked Johnny what he thought about raising kids upstate, and he was happy with it. So we moved home. Well, near home.”

Gillibrand’s move to Hudson was carefully calculated. The town is in the southern part of the 20th Congressional District, a region that sprawls to Lake Placid in the north and almost to Binghamton in the west. Registered Republicans outnumber Democrats almost two to one, but Gillibrand learned that Clinton and Spitzer had rolled up large majorities in the district in 2000 and 2002. She theorized that a moderate Democrat could win there under the right circumstances. She contemplated running in 2004, but Clinton, now something of a Gillibrand mentor, suggested the political climate would be better in 2006.

“My parents and husband have been worried about the coverage,” says Gillibrand. “I told them, ‘Give me six months, and I will make it better.’ People meet me, they like me. I work hard.”

With George Bush’s approval ratings at an all-time low, the 2006 electoral environment was, in fact, ripe for Gillibrand. And Republican incumbent John Sweeney was imploding. He had recently been photographed puffy-eyed at a Union College fraternity party and was thought generally to have “gone Washington” by many of his upstate constituents.

Gillibrand hit her mailing lists hard, raising a startling $2 million by the spring of 2006. Still, the Rahm Emanuel–led Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee remained skeptical. In May 2006, Emanuel dispatched Representative Steny Hoyer to check on the race at a fund-raiser. “Hoyer was there, but he seemed checked out,” recalls Bartley. “But then Kirsten got up and start talking about the race and how it was winnable, and people started clapping and he started paying attention.”

Emanuel upgraded Gillibrand’s candidacy from doubtful to winnable on the big congressional map in his office at the DCCC. Resources began to pour into her campaign. Clinton communications director Howard Wolfson signed on to help Gillibrand, and Clinton gave her some of her own coveted fund-raising lists.

Tracking polls showed the race was even going into the final week. Just one week before the election, however, a confidential police report was leaked to newspapers. Rumors had long circulated that state police had been called to Sweeney’s home in 2005 to respond to a 911 call from his wife alleging spousal abuse. The Sweeney campaign contended the timely leak was orchestrated by Gillibrand’s campaign, specifically Wolfson (Wolfson won’t comment).

“We had a press conference about it, and I heard a reporter talking to Wolfson, and he was feeding him details that hadn’t been released yet,” a Sweeney aide told me.

Gillibrand has never denied that her campaign was the source of the leak despite being asked about it several times. She defeated Sweeney by six points.

I met Jonathan Gillibrand at the Dubliner, a Capitol Hill restaurant. A 39-year-old British national, Jonathan has kind eyes, a shy demeanor, and the look of a man who is not unhappy to pop out of the house now and then for a quick pint of Guinness. He is, essentially, the antithesis of his warp-speed wife.

The couple met when Jonathan was dating a friend of Kirsten’s in 1999 and Jonathan was getting his M.B.A. at Columbia. When her friend stopped seeing Jonathan, Kirsten asked if it was okay if she contacted him. They bonded over their shared Catholic heritage and attended Mass at St. Ignatius, on the Upper East Side, on their second date. They were married in 2001.

Gillibrand gave birth to her first child, Theo, in 2003, at the age of 36, when she was working at Boies, Schiller in Albany. She became pregnant with Henry shortly after she was elected to Congress. On May 14, 2008, she spent twelve hours on the floor of the House before going into labor. The birth of Henry Nelson Gillibrand was announced the next day to a standing ovation on the House floor.

The Gillibrands moved to Washington, D.C., when Kirsten became a congresswoman, in 2007, but they were still spending weekends in Hudson. Now they live almost exclusively in Washington. Jonathan works for a Washington real-estate investment trust. To take care of the kids after school or day care, the couple employs a babysitter or relies on family for help. Jonathan is not much interested in Washington political life. When we met in Washington, he told me about an exotic-car convention he was planning on attending in Florida. “That’s much more my kind of thing,” he said with a wry smile.

A friend of the family says Jonathan supports Kirsten’s political ambitions but is worried about the effect her career may have on their family. “When she was thinking of making her name available for the Senate, he said, ‘Sure, throw your hat in the ring,’ ” the friend says. “But he never thought she would get it. Now he’s freaked out about the loss of privacy and his wife traveling so much.” When I asked Gillibrand about Jonathan’s concerns, she said, “My husband and I talked about the appointment. We said, ‘Is this something that we are prepared to do as a family? Would I be good at this? Is this something where I could make a difference?’ And we decided that the impact you can have as a senator is extraordinary, because you could have a voice on all issues.”

Gillibrand is, by all accounts, a dedicated parent. She drops off Theo at preschool and Henry at day care before her workday begins and tries to be home with them at night as early and often as possible. As a congressional representative, she would sometimes bring Theo to the House in the evenings. “They have a cloakroom that has hot dogs and peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches and candy. For him it was, ‘Oh, I want to go with you to the Capitol Building!’ ” While the large number of representatives allowed her to shift the time she spent presiding over the House, the Senate has proved less flexible. Shortly after her January appointment, Gillibrand was assigned a “gavel time” of between 5 and 7 p.m. on days the Senate was in session. Gillibrand went to the Senate leadership and explained that the time conflicted with Theo and Henry’s dinner-and-bedtime routine. She asked if she might switch with a senator without small kids. She was politely told no. (The decision was later reversed.)

Gillibrand is aware that being the mother of two young children can be a powerful connecting tool for a politician. “I hate being away from my kids, but it’s no different than for a mom who is cleaning out offices from 4 p.m. to midnight,” she says. “My burden isn’t any greater than hers.” She recently introduced legislation calling for stronger testing of potential toxins in baby products and, during a series of satellite interviews with New York television stations, deftly worked in the idea that she, “as a mother of two small children, was shocked to find this kind of stuff in products I use every day.”

Gillibrand’s voting record on women’s issues is brief, but strong: She has a 100 percent rating with naral Pro-Choice America, and has been active on equal-pay legislation. And she’s built a network of powerful women allies. One of the first calls Gillibrand made when she was contemplating a run for Congress was to a Hillary Clinton connection, Judith Hope, a Democratic National Committee member and founder of the Eleanor Roosevelt Legacy Committee, a fund-raising project aimed at encouraging pro-choice women to run for office. Once Gillibrand was appointed senator, Hope and other activists quickly rallied around her. “The Eleanor Roosevelt types now see Hillary’s seat as a woman’s seat,” says a frustrated staffer for a potential Gillibrand opponent. “They’ve completely circled the wagons around Gillibrand.”

With women still badly underrepresented in the Senate, liberal women activists are reluctant to bash Gillibrand, even if they disagree with her on policy issues. I got an earful from a Gillibrand friend when I suggested her House views were out of step with many Democrats. “This is more important than another yes vote on immigration,” the activist told me. “We have the opportunity to keep a woman in the Senate from a major state like New York. The stakes are too high for ideological purity.”

Gillibrand arrived in Washington in 2007 with a reputation as a dragon slayer from a swing district. She was given plum assignments on the House Agriculture and Armed Services committees. The New York Times wrote a multipart series about her first year in office. Resentment within the delegation began almost immediately. Much of the ill will centered on the perception that she seemed to feel entitled to special treatment because she had upset a Republican incumbent. “Leadership does a lot to protect candidates from marginal districts,” says a staffer of a senior New York representative. “But she flouted the conventions. She placed calls to Charlie Rangel and then to Speaker [Nancy] Pelosi trying to get better committee assignments. That was good for her, but not for the delegation.”

Fellow Democrats also took exception to the fact that Gillibrand bucked the party line on hot-button issues. She joined the Blue Dog Democrats, an alliance of mostly southern fiscally and socially conservative Democrats. She earned a 100 percent rating from the NRA, in part for her vote in favor of a measure that limited information sharing on gun buyers between the ATF and FBI—a position vehemently opposed by big-city mayors including Mike Bloomberg. (The tension between the mayor and the senator continues. Bloomberg was a major supporter of Caroline Kennedy’s Senate bid, and Gillibrand’s representatives suspect his people have been responsible for much of her negative press.) She voted in favor of the controversial measure to label New York a “sanctuary city,” and to potentially cut off federal aid until municipal authorities begin actively curbing illegal immigration. And she was one of a small minority of Democrats to vote against the TARP bank-bailout legislation, a move said to enrage House Speaker Pelosi.

Despite her critics’ objections, Gillibrand’s voting record proved politically effective, at least in the short term. In 2008, she faced a well-financed Republican in business executive Sandy Treadwell. He outspent her $7 million to $4.5 million, but while his campaign was largely self-financed, Gillibrand raised more money from outside sources than any other freshman representative elected in 2008. Her conservative positions on economic issues, guns, and immigration were catnip to her upstate constituents, leaving Treadwell boxed in. “When she voted against TARP, we knew we were finished,” a Treadwell aide says. “She was smart. She didn’t leave us any openings.”

The Treadwell campaign tried to exploit Gillibrand’s work for Philip Morris, but it lacked a key weapon. “We looked everywhere for video of her speaking at an anti-tobacco rally,” says the Treadwell adviser. “There’s nothing. She was too smart to leave anything that you could use in a negative ad.” Gillibrand defeated Treadwell last November by a margin of 62 to 38.

“I assure you that we will be united in our opposition to her,” says one early rival. “She’ll be reelected over my dead body.”

When Barack Obama nominated Hillary Clinton to be secretary of State in November, Governor David Paterson made a special effort to find a woman to fill Clinton’s seat. The potential 2010 Democratic slate headed by Paterson otherwise threatened to feature all males, perhaps all from downstate, no less. The list of women for Paterson to choose from wasn’t especially long. Westchester congresswoman Nita Lowey, who would be 73 before 2010, quickly withdrew her name from consideration. It was unclear if Manhattan congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, who went on a Hillaryesque listening tour, would have statewide appeal. Paterson liked Randi Weingarten, the president of the United Federation of Teachers, but her lack of electoral experience made her a risky choice.

Enter Gillibrand. Not only would she provide the gender diversity Paterson sought, but she was popular upstate, had a good relationship with the Clintons, and had powerful financial connections—all of which could help get her elected and help the beleaguered Paterson in his own 2010 campaign. A Washington Post blog posted a list of contenders and placed Gillibrand as the second favorite, trailing only Nassau County executive Tom Suozzi.

But whatever hopes Gillibrand had for winning the seat were all but ended when Caroline Kennedy emerged as a candidate. Recognizing that she could not compete with Kennedy’s star power, Gillibrand instructed her allies only to let the governor know she was still interested and not to lobby on her behalf. She completed a questionnaire Paterson requested, but otherwise kept out of view.

That all changed when Kennedy removed herself from consideration. On the evening of January 22, Paterson called Gillibrand in Washington and asked her if she was still interested in the job. He told her he had not made his final decision, but he requested that she fly to Albany and await further instructions. Paterson also asked her to make one phone call. One of the few constituencies the increasingly embattled governor could rely on was the gay community, and Gillibrand had expressed support in interviews for civil unions instead of legalizing gay marriage. Paterson instructed Gillibrand to call Alan Van Capelle, executive director of the Empire State Pride Agenda, and promise she would reverse her position. Gillibrand made the call, and then headed to Albany. With rumors still circulating about whom Paterson might choose, Gillibrand went to bed uncertain of her fate.

Shortly after 2 a.m., Gillibrand’s cell phone rang, and Paterson greeted her with “Good morning, Madame Senator.” Gillibrand thanked the governor, hung up the phone, and promptly advised an aide to leak the news to the New York Times before Paterson could change his mind.

In Washington, the New York delegation was apoplectic. Representatives Steve Israel, Jerry Nadler, and Maloney all believed they were being seriously considered for the post. “We thought Paterson had two real choices,” said a senior staffer of one of the contenders. “He could name a celebrity like Caroline, someone so huge that she’s going to get her phone calls returned. Or he was going to name a kick-ass legislator who can run circles around the other legislators. Paterson went a third way.”

When Paterson asked Israel, Nadler, and Maloney to join him in Albany for the announcement as a sign of unity, they declined. Carolyn McCarthy immediately promised to challenge her in a primary.

The delegation’s mood didn’t lighten at Gillibrand’s appointment-announcement press conference. Gillibrand walked past State Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver with barely a hello but was seen talking animatedly with D’Amato. When the camera went wide, there was D’Amato, standing closer to Gillibrand than Paterson was. “You could hear heads exploding,” says a Gillibrand critic. “We just couldn’t believe what we were seeing.”

Gillibrand says she expected the vitriol with which her colleagues met her appointment, but she was still stung by it. “I was hurt but not surprised,” she says. “I thought they were my friends. They came to campaign for me. They raised money for me. I’ve called all of them and asked them to lunch.” She lets out a little smile. “Some of them don’t want to have lunch with me.”

It’s later in the day, and Gillibrand is scheduled to film interviews in a Senate studio with upstate New York television stations. She detours into a dressing room to adjust her makeup, and Bethany Lesser, a press aide, whispers, “Senator, you don’t have time. You look fine.” Gillibrand ignores her. “Bethany, let me tell you a story. There was a press conference on a windy day where I didn’t look my best, and that was the picture my opponents used in negative ads for two years.”

Gillibrand’s first hundred days in the Senate brought a new set of problems. There were questions about her legitimacy and experience. “There was a bit of ‘Uh-oh, can she handle this?’ ” says a top aide to a Senate Democrat.

Gillibrand has also been accused of flip-flopping on policy issues with an eye toward the 2010 election. Despite her “sanctuary city” vote in the House, she wrote a letter to the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security in February asking that the agency stop its raids on residences. In 2007, she had co-sponsored the renewal of legislation requiring the federal government to delete information learned from handgun background checks after 24 hours. Shortly after being named senator, she voted to repeal that provision.

As police sweep her car at a checkpoint near the Capitol, I tell Gillibrand about a remark Schumer made to me. “One of the things I like about Kirsten is I can tell her when she’s doing things wrong. She takes it well,” Schumer had told me. “I won’t try and minimize the mistakes she’s made, but I don’t think they’re insurmountable at all. She’ll learn.”

It’s Schumer, more than anyone, who is responsible for Gillibrand’s relaunch. At Gillibrand’s lowest point, shortly after the Times tobacco story, New York’s senior senator agreed to cooperate with (and some suspect he orchestrated) what was viewed by some as a Times makeup call, a front-page story about how Schumer was taking Gillibrand under his wing. The piece implied that Schumer was supporting Gillibrand because he could manage her. The message Schumer meant to send was clear: He is on Gillibrand’s side and expects others to be as well. “I don’t endorse eighteen months out,” Schumer says. “But I can tell you I’ll be endorsing her at the right time.”

Gillibrand insists she’s not, as some observers have suggested, Schumer’s puppet. But she doesn’t deny he’s a mentor. “It’s all true. I had dinner with Chuck in New York last week,” she told me at one point. “And Chuck told me what I was doing wrong. He told me what events I should have skipped and what ones I should have gone to. And I listened. He knows a lot.”

Gillibrand’s standing has also been enhanced by Barack Obama. In May, Long Island congressman Steve Israel, arguably Gillibrand’s most formidable potential primary opponent, was a day away from announcing his candidacy. Staff had been hired, and a website was about to be launched. But then Israel was called to presidential chief of staff Rahm Emanuel’s office and two days later received a call from the president. That day, Israel announced he would not run.

The Gillibrand camp spun Israel’s withdrawal as a sign of support from Obama. It certainly had that appearance, but the president’s motives were more far-reaching than that. The filibuster-proof 60-seat majority Democrats will enjoy if Al Franken is seated is fragile. The Democratic leadership doesn’t want to waste precious resources on internecine warfare. “The Washington Establishment hates change,” says a Democratic Senate staffer. “There is no way Schumer and Harry Reid are going to abandon her. They’ll give her some kind of legislative trophy that she can put her name on. And if you’re a lobbyist, you’re going to be like, ‘What’s in it for me to take a flier on someone else when the smart money’s on Gillibrand?’ ” Late last week, Carolyn McCarthy announced she wouldn’t run either.

Maloney, meanwhile, is said to be on the verge of announcing a bid to unseat Gillibrand in the 2010 Democratic primary. “The commercials write themselves,” says a top Manhattan political consultant. “Big Tobacco. Immigration. Guns. It’s all there. And she has no record. She has no base of goodwill to build on.” Says one early rival, “I assure you that we will be united in our opposition to her. She’ll be reelected over my dead body.” Names that have surfaced on the Republican side as possible 2010 opponents include former governor George Pataki and Congressman Peter King.

Gillibrand’s fund-raising ability may be her most powerful weapon. Although she alienated some of her Wall Street backers with her vote against the Bush bailout bill while she was in the House (Crain’s New York Business editorialized that the vote disqualified her from Senate consideration), she’s been working to address that. In March, she held a fund-raiser with Wall Street executives hosted by Bill Clinton at the Upper East Side mansion of corrugated-box millionaire Dennis Mehiel, Carl McCall’s running mate in 2002. At that event, she left no doubt that she understood what her audience expected of her. “I used to represent a rural, conservative Republican district,” Gillibrand told the crowd. “Now I represent all of New York, and I have to represent all New Yorkers. I know the difference.”

Gillibrand raised $250,000 at the event. On April 6, she reported amassing $2.3 million in the first quarter, a substantial number that’s all the more striking in the current economic climate. Maloney has not displayed the ability to raise large amounts of money during her career. She currently has $1.3 million in the bank, enough to buy roughly one week’s worth of television ads. Polls show Pataki even in a theoretical race against Gillibrand, but he has expressed no interest. King, who is not well known outside his own Long Island district, would be hard-pressed to match Gillibrand’s war chest.

Gillibrand, of course, has a clear vision of the future. As we say good-bye—she’s off to make fund-raising calls—she asks, “Did you get what you need? Did I tell you if I wasn’t a lawyer, I wanted to be a journalist? I love getting at the truth. My favorite is Greta Van Susteren.”

For a fleeting moment, a look of concern comes over Gillibrand’s face, and she touches my arm. “Is this going to be okay?”

But before I can say anything, the smile returns. Kirsten Gillibrand believes again. “This will be okay. I know it will be okay.”