On an early-October night here in Kingston, a town about a hundred miles north of Manhattan, it was 2007 all over again. A white banner hung over a Colonial-style function hall with the message ULSTER COUNTY WELCOMES RUDY GIULIANI, and attendees were lined up in the autumn chill to pick up their tickets ($95 for dinner, $250 for a private reception). Inside, the guest of honor had just arrived in the main dining room to a standing ovation, and now chaos was breaking out. In many quarters, Giuliani’s disastrous 2008 presidential campaign—$60 million, no delegates—has branded him something between a failure and a punch line. But among this crowd of Republicans, desperate for a savior to lead their party back to power in New York and Washington, this was the same Rudy they had known and loved before his turn on the national stage. The county GOP chairman, Mario Catalano, was giddy at the turnout of 450. (“Normally, if we have 250, that’s big,” he said.) At the moment, however, Catalano was trying to regain order amid a scrum of flashing cameras and autograph-seekers clutching their copies of Leadership or their photos of Rudy and Joe Torre in firefighters’ helmets with the Yankees logo. “Folks, I am begging you to please remain where you are sitting!” Catalano pleaded. “I will walk the mayor around the room. Because right now we’re creating a terrible security hazard.”

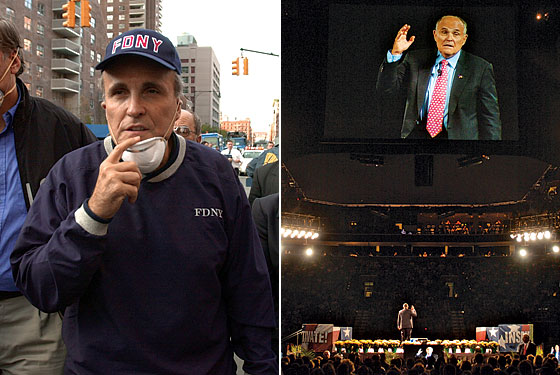

At that, Giuliani made his rounds, grinning and twinkly-eyed, floating on the star power that supercharged him on September 11. He wore a pin-striped suit with an American-flag pin on his lapel and, at 65 years old, seemed as vigorous as ever.

“Future governor!” exclaimed one man, pumping Rudy’s hand with glee.

“There’s been a lot of talk these days about the mayor’s political future,” said Catalano, now back at the podium, “and the potential for him to run for governor of New York.” Applause ripped through the room. “Am I to assume that you guys are in favor of that?” A chant broke out: “Ru-DY! Ru-DY!”

And then Giuliani took the stage. “We need your help, Rudy!” someone called out. He basked, then delivered a seminar on the New York economy. “To increase expenditures of the state by 9 or 10 percent this year is totally irresponsible. All that’s going to do is require that taxes be raised even more. If you want to know how you create jobs, you lower taxes.”

He carried on with a big smile, the applause washing over him. “I faced this problem in 1993, when I became mayor of New York City. And everyone knows about the crime problem. But there was another problem—we had a financial crisis. I took a bold approach. I reduced spending by $2.3 billion. I cut everything that had to be cut. I cut things that quite honestly shouldn’t have been cut … I cut them because I had to. I didn’t mind that I was picketed every day.”

It’s not a bad spiel. And in Kingston, his listeners were wound up. “He’s probably the next governor of New York,” exclaimed a sixtyish man in a matching maroon shirt and tie who would identify himself only as Pete. “I believe he’s gonna run. I told him, ‘You have to run. We got the party. All we need is a man to lead us.’ ”

September 11 transformed Rudy Giuliani from a mayor with marital problems and fast-fading popularity into an iconic figure, a heroic leader who steps in when times are hardest. It’s an image that’s made him a plausible candidate for just about anything, and helped him draw millions of dollars in speaking and consulting fees. It’s also a very hard act to follow: What’s a worthy sequel to those terrible, glorious weeks?

For a man defined by his certitude and personal force, his presidential campaign was oddly halfhearted, an echo of his abortive Senate bid eight years earlier. After his 2008 campaign, Giuliani all but vanished from the public eye. But David Paterson’s haplessness opened a door. The Rudy-for-governor buzz built for months, providing a failed White House contender with an opportunity to reintroduce himself, on television (Meet the Press panelist, CNBC Squawk Box guest) and on the front pages of the Times and Post. He seemed to draw energy from all the attention. (Although his appearance with Mayor Bloomberg reminded many New Yorkers of what they didn’t like about him.) The rumblings of a run even brought the ultimate compliment, the attention of the Obama White House—leading to that clumsy attempt last month to persuade Paterson to stand down, clearing the way for Andrew Cuomo. (While recent polls consistently show Giuliani thumping Paterson by double-digits, the reverse has mostly been true with Cuomo.)

But in Kingston, Giuliani was coy. He hardly seemed prepared to commit to saving New Yorkers from their dire fiscal fate. That much was clear when, just before his speech, Giuliani fielded questions. “I’m here to help,” he explained. “I’m not here to dip my toe in the water.” So when would he make up his mind? “I’ll turn my attention to that after the elections are over and figure it out,” he said. “There’s still plenty of time.”

Hoping to learn more, I met with Giuliani last month in the sleek and modern offices of Bracewell & Giuliani, the Houston-based law firm where he has been a partner since 2005 and where he spends about half his time. Rudy was running late. It was September 8, the week of the sacred anniversary, and Giuliani was observing it this year with, among other things, a pretaped guest appearance with his wife, Judith Giuliani, on The View. Seated on a canary-yellow couch, he explained to Barbara Walters how seeing someone jump from the burning towers changed him forever. Walters was dazzled. “Should he run for president?” she cooed to Judith.

Judith smiled and dodged the question. But when Rudy marched into a Bracewell conference room—“Let’s eat!” he said, going bulgy-eyed at the catered sandwich plates—he sounded like someone who thinks more about being president than about being governor. He opined on health care (no big government), Afghanistan (send more troops), and Iran (be wary of meddling in their politics) on the way to rendering his verdict on Obama: “I thought we would get more of a moderate,” he said. “I was expecting more like Clinton than more like Jimmy Carter.”

In this context, the subject of running for governor seemed less inspiring to him. He gave the distinct impression of a man for whom the state job may not be quite enough. Friends and foes alike say they wonder whether Giuliani, who obviously considers himself fit to lead the United States of America, could really want to relocate to the state capital and play ringmaster of the Albany circus. “It is a valid question,” he told me. “Can a governor make a difference, and how much of a difference? I believe the politics of the state—this is not a partisan judgment at all, because both parties bear equal responsibility for it—can in the nicest way be described as dysfunctional. And I guess that whole dispute with the Senate is the perfect example.”

Would a man like Giuliani really want to become ringmaster of the Albany circus? “It is a valid question,” he tells me. “Can a governor make a difference? And how much of a difference?”

Even Rudy’s closest advisers concede the limited allure. “It’s not an easy job,” says his longtime aide and confidant Tony Carbonetti. “You gotta trek up to Albany, you gotta fight with the State Senate, you gotta fight with the Assembly. It’s a daily grind.” (On a more personal front, Giuliani said he’d have no problem with Albany. “They’ve got a lot of good golf courses right around there,” he says.)

As mayor, Rudy actually had a decent relationship with a heavily Democratic City Council. “Having Peter Vallone as the speaker was very valuable,” he says. “He was somebody I could work with.” But Rudy understands that Albany can grind down even the most determined governor. “I thought Eliot Spitzer had the right strategy,” Giuliani says. “For obvious other reasons, he never had a chance to execute it correctly—which was that you cannot do this ‘three men in a room’ thing. A governor has to be able to develop coalitions in the Legislature, as opposed to just convincing, you know, the majority leader or the speaker. Whether a governor can accomplish that or not, given how this has become so entrenched, I don’t know.”

The elephant in the room is Sheldon Silver. During his City Hall years, Giuliani clashed repeatedly with Silver. (In late 2001, for instance, Giuliani’s spokeswoman said Silver would “go down in history as the speaker who cost the city the most money.” Silver later said that Giuliani’s 9/11 heroism had been exaggerated.) “The most powerful man in Albany is Shelly,” says former Giuliani adviser and Manhattan Institute fellow Fred Siegel, who still occasionally talks to Rudy. “He may have no vision whatsoever, but he is wily. Does Rudy really want to spend eight years butting heads with Shelly Silver?”

“Having the ability to set the revenues [as mayor] ultimately meant I was able to straighten out the budget and get the tax reductions I wanted,” Giuliani says. “If I wasn’t able to set the revenues”—he shrugs—“I’m not sure.”

It was less than a ringing declaration of his intentions. And more than a few New York politicos have the same impression. “I’m not trying to rain on his parade, but I don’t see any parade,” says Mike Long, the Conservative Party chairman. “I can’t find a Republican statewide who says, ‘I spoke to Rudy, and he said he’s gonna do this.’ There are a lot of Republicans who would like him to run, but I don’t see any evidence.”

So if he doesn’t run, what exactly is all this flirting about? Part of the answer is that Rudy Giuliani is more than a politician. He is also a businessman.

One of the most spectacular failures in presidential-primary history concluded on January 30, 2008. That was the day Rudy Giuliani, fresh from his 15 percent, third-place showing in the Florida Republican primary, appeared next to John McCain and announced he was dropping out and endorsing his former rival as the best man for the job. “Obviously, I thought I was that person,” Rudy said at the time. “The voters made another choice.”

No one—not John McCain, not Bill Clinton—walked away from the 2008 presidential campaign as diminished as Rudy Giuliani. He entered the campaign with one of the most valuable brands in American politics and drove it straight into a tree. It’s hard to chronicle all the embarrassments: the Kerik indictment, the stories about taxpayer funds spent for his then-girlfriend Judith Nathan’s security; that bizarre cell-phone call he took from Nathan during a 2007 speech to the NRA.

And then there was his cockamamy campaign strategy, in which he sat out the Iowa caucuses, skipping a contest that riveted the world for a month, and competed halfheartedly in New Hampshire and South Carolina. By the time he made his infamous last stand in Florida, hoping that weeks of appearances at NASCAR tracks and Little Havana parades could make up for the ground he’d lost, it was too late.

Today, Rudy Inc. offers myriad excuses for the debacle. Giuliani says fund-raising in the crowded field was harder than he expected: “I wish I had figured out that we weren’t going to raise $100 million.” Giuliani also wishes he hadn’t skipped Iowa, a decision he attributes to advisers. “My instincts originally were, if you lose, you gotta go down fighting. You can’t allow yourself to lose a primary. I think I should’ve fought Iowa harder. That was the beginning of becoming irrelevant.”

But the irrelevance was only part of the problem. Well aware that a pro-choice, thrice-married, and occasionally cross-dressing New Yorker would be hard-pressed to win over the social conservatives who control the Republican nomination process, Rudy changed his spots, putting a dark and often sneering emphasis on national security. He charged that Democrats “do not understand the full nature and scope of the terrorist war against us” and warned that America would suffer “more losses” under their approach. (Obama called this “taking the politics of fear to a new low.”) His top campaign allies included Sean Hannity and Pat Robertson, the latter of whom endorsed Rudy on the grounds that he best understood “the defense of our population against the bloodlust of Islamic terrorists.” And later there was his memorably taunting speech at the Republican convention, in which he ridiculed Obama’s experience—“Barack Obama has never led anything. Nothing. Nada”—and literally laughed out loud when he uttered the words “community organizer.” And his relentless focus on the aftermath of the World Trade Center attack allowed him to become a self-parody, captured memorably by Joe Biden: “There’s only three things he mentions in a sentence—a noun and a verb, and 9/11.”

In May 2008, three months after leaving the presidential race, Giuliani appeared at a Times Square press conference with an unlikely partner: one Vitali Klitschko, a Ukrainian boxer known as “Dr. Iron Fist” for his Ph.D. in sports science. In addition to smashing men in the jaw, Dr. Klitschko dabbles in politics and was running for mayor of the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. Giuliani, who says he has made many friends in Eastern Europe through his business ventures, recalls that Klitschko approached him to “figure out an anti-corruption program for Kiev” (which Rudy pronounced Keev). “Reform is possible if you have the right candidate and the right set of ideas,” Giuliani declared at the press conference, the buff fighter looming over him in a dark suit. “Kiev can accomplish this.” But Klitschko wound up suffering a TKO at the ballot box, and today Rudy dismisses the work as “a really short assignment”—although he still predicts that Klitschko, who last month successfully defended his world heavyweight title, “will eventually be, God willing, the president of the Ukraine.”

Klitschko was not exactly an A-list client. And the episode suggested that after his national flameout, Rudy wasn’t in a position to be highly selective about where he took work. After quitting the campaign, Giuliani returned to his business ventures. But finishing behind Ron Paul and Fred Thompson in several states will put a dent in a man’s business brand. Giuliani’s speaking fees reportedly sagged as much as $25,000 from a peak of $100,000. More significant was the impact on Giuliani Partners, the business he founded weeks after leaving City Hall.

From 2002 through 2006, Giuliani Partners raked in more than $100 million from such Fortune 500 clients as Nextel, Delta, and Merrill Lynch. Today Giuliani says the firm has been downsized substantially. “The reality is that it’s about half the size it was before, and it’s doing about half the business it was doing,” Rudy says. “It’s doing very well for a much scaled-down business.” But not well enough to keep key members of Giuliani’s inner circle onboard. Carbonetti, for instance, recently ended his day-to-day duties to become a “strategic adviser” to Home Depot co-founder Ken Langone. In January, Rudy’s spokeswoman since his days as mayor, Sunny Mindel, also left. Rudy says the economy is partly to blame, along with his absence during the campaign. “Some of the clients didn’t have me around, so they left,” he says. One executive at a firm that competes with Giuliani’s suggests there’s more to it: “If you’re paying for someone’s judgment, you might not be as interested in that judgment after such a poorly run campaign.”

Giuliani Partners won’t name its clients, and ceased issuing press releases announcing its new contracts a bit before Rudy started running for president, so it’s impossible to know exactly whom he’s working for today. It’s clear that many of his past clients have moved on: Spokesmen for several companies with previously reported ties to Giuliani Partners—including Entergy, the Greater New York Hospital Association, and Aon Corporation—say their contracts ended long ago. Two senior employees for rival security firms say they never cross paths with Giuliani’s firm nowadays. “Frankly, they’re just not seen or heard from,” says one. (The same security-firm employee recalls working with the Mexico City government shortly after Giuliani Partners completed a 146-point crime-fighting plan at a cost of $4.3 million. Crime rates in the beleaguered city failed to drop substantially. The officials, says this source, “were all just pissed off–slash–laughing that what they got for a product was completely useless.”)

One sign of life did emerge last month, when Giuliani Partners’ security division announced a deal with a little-known New York–based asset-management firm called Nine Thirty Capital. “We do the things that weren’t done,” Giuliani explained in a recent CNBC appearance. “We go check and make sure the transactions are taking place. We make sure the business really has the people that it says it has. We go into their reputations, their background.” The press release announcing the deal promised it would “help restore investor confidence in the financial system.” More likely, it’s about restoring confidence in Nine Thirty. The list of Bernie Madoff’s victims includes numerous references to the firm and its CEO, Stuart J. Rabin.

While Giuliani Partners may be fading, Rudy’s other big moneymaker—Bracewell & Giuliani—is faring better. Rudy now spends about half his time at the firm’s Sixth Avenue offices. While his Bracewell income isn’t public, a financial-disclosure form Giuliani filed during his presidential run showed a guaranteed base pay of $1.2 million per year, plus 7.5 percent of the firm’s New York revenues in 2006. “It’s going to be more profitable this year than it was last year. And last year was our best year ever at the firm,” Giuliani says. Dan Connolly, a Bracewell managing partner (and former Giuliani City Hall aide), says the firm made gross revenues of just under $300 million last year—up a handsome 50 percent from 2006.

When he first opened the Texas firm’s New York offices in 2005, Giuliani’s primary job was recruiting talent to join the firm. Now that Bracewell & Giuliani has a team of 65 in New York, Connolly says, Giuliani spends more time not just building but “work[ing] the business”—attracting and working directly with clients. Connolly recalls one meeting earlier this month, for instance, when Bracewell was a candidate to broker a major debt restructuring for a group of financial companies. Four firms were asked to give short presentations. The Bracewell team included Giuliani, who “played a very active role,” Connolly says. “What he brings to bear is the gravitas of someone with almost 40 years of experience in the law.”

Fortunately for Giuliani, Bracewell was well positioned to profit from a national economic belly flop. The firm’s Connecticut and New York City branches have specialized in bankruptcy cases and work involving distressed companies. During the market meltdown in September 2008, Bracewell announced an “Economic Recovery Task Force” that promised to help guide clients “through the legislative, regulatory, and enforcement challenges” posed by the bailouts. Although Connolly says Giuliani “was not actively involved” in that work, the press release announcing the task force did include a quote from Rudy praising the firm’s lawyers.

And even as Giuliani Partners works to smoke out the next Madoff, Giuliani’s firm is defending a top associate of the man himself: Frank DiPascali, Madoff’s long-serving chief financial officer, who recently testified about the Ponzi scheme that he “knew it was criminal, and I did it anyway.”

Giuliani was unapologetic when asked about DiPascali. “That’s what you do as a lawyer,” he told me. “You’re a doctor—you help people who are in trouble.” Giuliani even spun the case as a kind of public service, given that the Bracewell lawyer, Marc Mukasey, helped persuade DiPascali to cooperate with the Feds. “The government was on his side because he had done such good work cooperating,” Giuliani said, looking pleased with himself.

“When people come into this office, I don’t make a political judgment about them,” he continued. “We make a judgment as to whether or not they understand that we’re going to do it ethically and honorably, but if so, in most cases, you’ll take the client. That’s what you’re supposed to do as a lawyer.” Or, as Michael Corleone said in Giuliani’s favorite movie: “It’s strictly business.”

Rudy’s allies seem to enjoy ratcheting up the suspense around his decision. “It’s always difficult to anticipate Mayor Giuliani. No doubt about that,” says former Republican congresswoman Susan Molinari, now a lobbyist in Bracewell’s Washington, D.C., office. But in other quarters, patience is starting to wear thin. Earlier this year, the state party’s outgoing chairman, Joe Mondello, asked him to make a decision by early fall—something that clearly hasn’t happened. And now that another GOP contender—former GOP congressman Rick Lazio, who initially deferred to Giuliani in the 2000 Senate race—has announced his own candidacy, some Republicans are getting tired of Rudy’s Hamlet act. “People are eager for him to make a decision one way or another, just for the health of other Republicans who may want to run,” says one person who has worked for Giuliani.

Some people see the recent effort to install an ally in the job of New York GOP chairman as a sign of his engagement in state politics. But despite a round of lobbying by Giuliani and aides like Carbonetti, the job went to Richard Nixon’s son-in-law, Ed Cox. And now Giuliani has, at best, an uneasy truce with Cox, who has recently been urging him to take on Democratic senator Kirsten Gillibrand next year. Even though a recent poll had Giuliani beating her by nine points, Giuliani laughs off the idea. “My value is in running things,” he told me. “Commenting is great, but I get to do that anyway on television and radio and [in] op-ed pieces.” “It’s a job that we have discussed in the past, and he just has no desire to do it,” Carbonetti says.

It seems entirely possible that Rudy is playing a game—one that is about his own self-worth, and also about his net worth. Stringing things out is a form of free advertising.

Which is why it seems entirely possible that Rudy is playing a game—one that is about his own self-worth, and also his net worth. He enjoys the attention, enjoys being pursued, can’t stand to be out of the limelight, even if a job like, say, governor of New York he sees as beneath him. And stringing things out is a form of free advertising. “That can’t be bad for business,” says Jay Jacobs, chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee. “There is no upside for him to shoot it down, and there is a lot of upside for him to continue. But at the end of the day, I think the risks of running far outweigh for him the benefits. And I don’t think he’ll pull the trigger.”

The polls are telling a clear story. Republican congressman Pete King, a Giuliani ally, says the impact of another run on his business has come up in their conversations. “You take a year away from your business,” King says. “High-powered business clients rightly demand a lot of attention.”

And Jacobs points out a bigger business problem. “If he runs and doesn’t win, then the Giuliani brand has really lost a heck of a lot of value.”

In late July, Giuliani was the featured speaker at a breakfast in a midtown hotel. The event was treated as another testing of the political waters. But this time Rudy’s audience was not a political one. The breakfast was sponsored by Crain’s New York Business. Speaking before the room of dark-suited businessmen, Rudy was blithe and breezy—bashing liberals, gauging the economy, and condemning Albany’s dysfunction.

During the question-and-answer session, Rudy took a question about the New York GOP. What hope was there for the party if he didn’t run for governor, and if former governor George Pataki didn’t take on Gillibrand? Giuliani smiled. “There’s no question that if you have to rely on George Pataki and me, you’re in deep trouble,” he joked. “We should be moving forward with dynamic new candidates.”

Later, Rudy was asked whether he would, in fact, run for governor. He demurred as usual. But the event’s moderator, Crain’s editorial director Greg David, interjected, “Not only do you seem to be uncertain, it seems to me that you’re unprepared to run.”

Giuliani looked miffed. “I thought you were going to say based on my speech and my performance today, I seem to really know the issues really well.” But he didn’t call the comment unfair, or refute it exactly. “If I do decide to run,” he continued after a pause, “then I will think more deeply about the issues than I have.”

New Yorkers may be waiting quite a while for his wisdom.