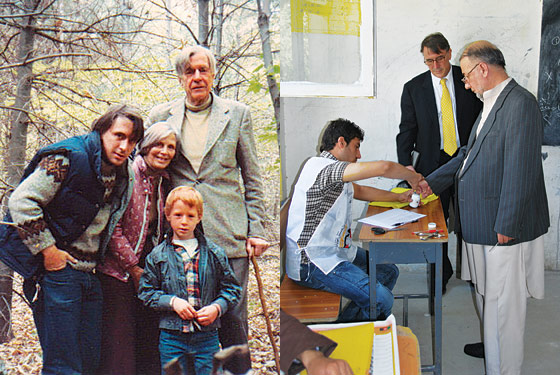

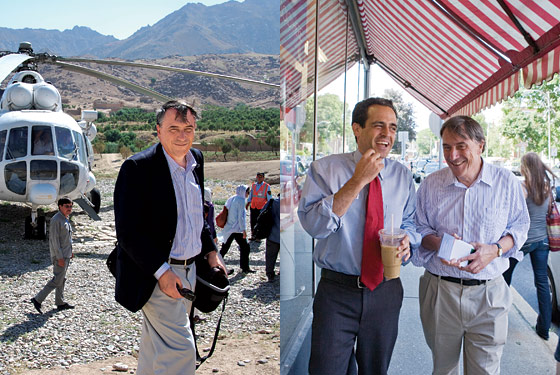

In retrospect, from the moment in July 2009 when Peter Galbraith found out about the ghost polling centers being established all around Afghanistan, his future path was fixed. Galbraith was then second in command of the U.N. mission in Kabul, and he and several election officials had helicoptered onto a hilltop near the city of Khost, a creepy, bunkered spot where contractors were building fences and digging ditches to keep the Taliban out. The situation looked medieval.

The country’s presidential elections were set to take place in a little more than a month, and preparations had begun. Local officials in Khost told Galbraith of polling places deep in Taliban-controlled territory. There were 175 polling places in the region, one U.N. official told Galbraith, and more than 75 were in areas so far beyond the government’s control that they would not be monitored, and would likely not attract actual voters, but would still be included in the official tally. Galbraith was suspicious. The U.N.’s political-affairs staff had long believed that Afghan election officials were more interested in reelecting President Hamid Karzai than in ensuring an honest election; here, Galbraith saw a potential mechanism for their fraud. “The people who were running the election,” Galbraith said, “were the ones who were planning to steal it.”

Some of his colleagues may have agreed with him privately, though there was enormous pressure not to derail the election—the first the Afghans would run themselves. But if you knew Galbraith, the rest was predictable. His moral certainty would compel him to broadcast the issue loudly; his righteousness would cast the issue as the pivot on which the future of Afghanistan turned; his sheer bullishness would lead him to feud with his superiors; his myopia, when in the service of a cause, would blind him to the nuances of the broader mission. The sequence was as clear as collision physics.

Two months later, Galbraith sat in the office of his boss, Alain Le Roy, the head of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, on the 37th floor at U.N. headquarters in New York. Galbraith had left Afghanistan, after serving only fifteen weeks, and now he was being told he could not return—his escalating feud with his superiors had become irreparable, and senior members of the Karzai government refused to work with him. Galbraith seemed genuinely taken aback, and he asked what he was supposed to do. Was there another job at the U.N. for him? Le Roy was noncommittal. Six days later, on September 30, the U.N. released a statement announcing that Galbraith had been fired.

What was obvious at the time was that he would not go quietly. For a quarter century, Galbraith, now 59, has periodically slipped into the pages of the New York Times to declare that in some previously obscure corner of the world, America’s character was failing a moral test. In the eighties, as a Senate staffer, he flew into Iraqi Kurdistan and emerged with evidence that Saddam Hussein’s armies had committed acts of genocide; Galbraith performed similarly bold feats in Bosnia and East Timor.

Galbraith had powerful friends (Joe Biden, John Kerry, the late Claiborne Pell and Daniel Patrick Moynihan), and their protection gave him a freedom to stand on principle that diplomats rarely enjoy. He was one of a small group of humanitarians who, emerging at the end of the Cold War, began to redefine the ways liberals thought of American empire: not as a force to be feared but as the tool by which the rougher parts of the world might be bent toward justice. In her genocide history A Problem From Hell, Samantha Power called Galbraith’s work “heroics.”

Now all that was over. “I understood that the moment you get fired for taking a stand on principle, you’re finished as a diplomat,” Galbraith says. “People may admire you, but nobody wants to hire a principled diplomat.”

After his dismissal, something tense within Galbraith seemed to come unwound. “There’s something in my nature,” he says. “People don’t do these sorts of things to me and get away with it.” Shortly after he was fired, he began a very public campaign for vindication. The Times soon published a letter he had sent to Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (“a very well-written letter,” Galbraith told me) in which he accused his direct U.N. superior of having “blocked me and other [U.N. staff] from taking effective action that might have limited the fraud or enabled the Afghan electoral institutions to address it more effectively.” There had been, Galbraith alleged, “a cover-up.”

His campaign for vindication quickly became more aggressive, personal—and compromised. Last October, a newspaper in Oslo published a report that Galbraith had helped a Norwegian energy company secure the rights to a Kurdish oil field and, for his role as fixer, had a stake in the project that would likely win him tens of millions of dollars. In Bergen, Norway, reporters caught up with Galbraith while he was walking his Goldendoodle across a bridge in the rain, and they reported that he ran away from them, wet and grimacing.

Then, on MSNBC this spring to discuss Karzai, Galbraith appeared to accuse the Afghan president of being an opium addict. “Well, he’s prone to tirades,” Galbraith explained. “He can be very emotional. Act impulsively. In fact, some of the palace insiders say that he has a certain fondness for some of Afghanistan’s most profitable exports.”

The hosts were bewildered. “So you’re saying he’s got his own substance-abuse problem,” one ventured.

“There are, there are reports to that effect. But whatever the cause is, the reality is that he can be very emotional.”

By early September, when I visited Galbraith in Vermont, this fierce unspooling had seemed to come to a momentary rest, and he had entered what is for him a more subdued kind of retirement. He is writing a book about Afghanistan and Pakistan and has begun an unlikely political career, running for a seat in the Vermont State Senate that he is expected to win. But he remains fixated on his dismissal from the U.N., and has filed a claim challenging its legitimacy.

As the mission in Afghanistan has grown only more grim, Galbraith has reacquired some of his old reputation as a truth-teller. “Peter was the boy who said, ‘Hang on a minute, the emperor’s actually stark naked,’ ” says Margie Cook, an Australian who was the U.N.’s chief electoral adviser in Kabul. “And when he did that, the whole edifice collapsed.”

Galbraith’s understanding is even grander. “These fraudulent elections set back the international community’s mission in Afghanistan enormously,” he says. “It basically eliminated whatever chance there might have been to accomplish President Obama’s strategy. The fraud in the elections—and, frankly, the U.N.’s complicity—are literally killing American soldiers.”

That Galbraith would assign himself such a central role in the history of Afghanistan is not surprising to his peers. Like his sometime ally Richard Holbrooke, he has a reputation for liberal vanity—and the conviction that he can see clarity in political affairs where others see only a muddle. “Unlike Peter,” says one U.S. diplomat involved in the elections in Kabul, “I don’t assume things are important just because I’m part of them.”

And yet for this principle Galbraith sacrificed his career. Later this fall, a U.N. tribunal will hear his appeal. Its narrow claim is that he was fired unfairly, but Galbraith’s filings make clear that he will use the hearing to argue a broader point: that he was right about Afghanistan, and the U.N. and the Americans were wrong; and that the Westerners, gazing into the region’s murky politics, have insisted on seeing moral ambiguity where in fact the blacks and whites are perfectly stark.

Galbraith has long believed that the most difficult problems in American foreign policy can be solved by embracing moral principles rather than shirking them. And so there is another question embedded in Galbraith’s case, too: whether this approach could fix the broken adventure in Afghanistan, or whether, in the aftermath of the wars of the last decade, it is a naïve anachronism.

Peter Galbraith seemed, to the U.N. officials who hired him, a particularly American kind of headache. At the beginning of 2009, Richard Holbrooke had just been appointed Obama’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, and he had urged Ban Ki-moon to appoint Galbraith in Kabul. The man for whom Galbraith would be working in Afghanistan was a Norwegian diplomat named Kai Eide, an old friend of Galbraith’s but an equally strong, rivalrous personality. The U.N. couldn’t really say no to Holbrooke—the State Department usually gets what it wants. But there was intense trepidation. “If you appoint Peter Galbraith and Kai Eide together,” one of Ban Ki-moon’s closest advisers told the secretary-general, “it will end in tears.” But by June, the two were working side by side.

The aspect of Galbraith that stays with you is his fixed, almost physical focus. He is married now (for the second time), but when he was younger, he was enough of a ladies’ man that, when he once antagonized the CIA station chief in Zagreb, the spook listed all of Galbraith’s liaisons in a dispatch back to Washington. (“They were all adult, none of them working for the U.S., so it was none of his goddamn business,” Galbraith says.) He has a medium build and a flop of dark hair across his forehead, and he would scan as preppy if he took any notice of style at all; as it is, he comes across as a guy who has always believed he had the preppies’ measure. There are “difficult aspects to his personality—he can sometimes be abrasive,” says his brother Jamie Galbraith, a prominent liberal economist at the University of Texas. “It doesn’t yield him anything to climb the organizational ladder. The question for him is how do you get what you want.”

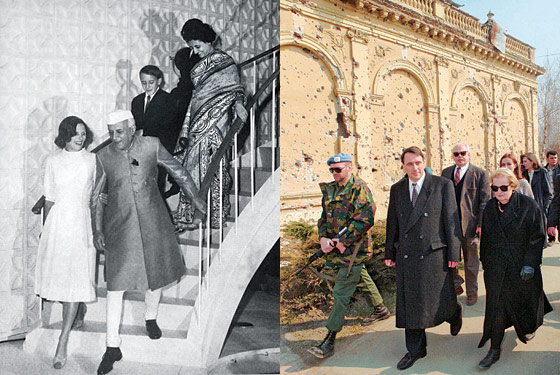

The word for all this is aristocrat. Galbraith’s father, John Kenneth Galbraith, was one of the most famous intellectual figures of the twentieth century, the economic historian whose book The Great Crash 1929 has helped shape the liberal moral imagination for the last 50 years. When Galbraith was 10 years old, President Kennedy appointed his father ambassador to India, during a time when the Americans were welcomed as better friends than the British colonists or the encroaching Chinese. One year later, visiting the Lahore horse show with his father, Peter met the child Benazir Bhutto, who would become his close friend when the two were at Harvard and eventually, after an episode in which the younger Galbraith helped win her release from Karachi Central Jail, the prime minister of Pakistan. (Bhutto was assassinated in 2007.) Galbraith has a photograph from 1962 in which his mother is leading then–prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru around the American embassy; he is serving as the boy escort to Nehru’s daughter Indira (a future prime minister herself), and Indira’s son Rajiv (another future prime minister) is trailing just behind. It is a kind of postcolonial fairy tale.

John Kenneth Galbraith was close to his sons until his death, in 2006, though he was intimidating too: witheringly logical and highly opinionated, six foot eight, with Rushmore features. But he gave his children something to defend. In Jamie’s case this was a critical theory of capitalism. In Peter’s, it was the beginning of a particular idea of how America might operate overseas—allying itself with the powerless, without seeking to remake their world.

In the immediate aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War, when the Reagan administration was strongly allied with Saddam Hussein, Galbraith (then a Senate staffer) flew into Kurdistan and emerged with documentation that the Iraqi troops were systematically rounding up and gassing their own people. In the Balkans, he directed the CIA to the mass graves at Srebrenica. As ambassador to Croatia, he gave tacit permission for the Iranians to ship arms through the country to arm the Bosnian Muslims and help turn back the Serb militias; this antagonized the CIA, which accused Galbraith of going rogue and persuaded Congress to hold hearings (Galbraith says he was acting under orders from the Clinton White House). Even his opponents concede that he was preternaturally effective, but he sometimes gave the impression of playing by his own rules.

This was in part because Galbraith had his own relationships and allegiances. For years, for instance, he had been personally close with the Iraqi Kurdish leaders; he had helped give their cause a profile in Washington, and prided himself on the ability to see American policy from their perspective. In the run-up to the Iraq War in 2003, Galbraith supported the invasion and wrote op-eds reminding Americans of Saddam Hussein’s poison-gas campaigns to slaughter his own Kurdish citizens. But as Operation Iraqi Freedom began, Galbraith could see that the Bush administration’s plans for Iraq would not include a separate Kurdish state. “They were seduced by the idea of a noble, nonsectarian, nonethnic Iraq,” Galbraith says, “when in fact the idea of Iraq to the Kurds was repulsive.”

But if the United States would not take up the Kurdish cause, Galbraith himself still could. While away from government service, he consulted for companies and foreign governments to help them develop their own natural resources—first in East Timor, then elsewhere. Now he began to work with a Norwegian oil company, DNO, that was interested in expanding its operations. Galbraith suggested Kurdistan. The legal status of the oil fields was not yet settled—Iraq did not yet have a new constitution—but Galbraith helped convince the Norwegians that any deal that they cut with the Kurds, who held the territory, would likely stick. “We wanted to create facts on the ground,” Galbraith says. For his role, he took an economic interest in DNO’s work in Kurdistan. One of the oil fields turned out to hold large reserves, and published reports have put the value of the stake that Galbraith shares with an investor at $55 million to $75 million. The moralist had become a millionaire.

There was something unseemly about the affair that colored Galbraith’s humanitarian reputation. Because he had not been working for the U.S. government in Iraq, he did not break any rules. But he had spent years making the case for the Kurds, publicly and privately, and urging American policymakers to support Kurdish autonomy. He had even helped shape the Kurdish proposal for the Iraqi constitution. That autonomy, when it came in limited form after the adoption of the Iraqi constitution, served to guarantee DNO’s investment. The Times, where he had published op-eds urging a three-state solution to Iraq, appended a correction last November, saying it “should have disclosed to readers that Mr. Galbraith could benefit financially from an independent Kurdistan that would not have to share oil revenues with Iraq.”

Galbraith chooses to see these ventures as humanitarianism by other means. “While I may have had interests,” he said last year, “I see no conflict.” Kurdish autonomy was, after all, a cause of his when most deemed it hopeless. And the money that oil brought to the Kurds, he says, has made a difference. Their cities have seen expansive reconstruction, and they are now extending utilities and building schools in rural areas. “But the most important tangible benefit is that Kurdistan is not dependent on Baghdad. Their bargaining position is so much stronger because Baghdad can’t turn off the spigot.”

Galbraith’s new wealth had more parochial consequences, too: It strengthened his own bargaining position. By the time he took the U.N. job in Kabul, he was liberated from any financial concerns, and his reputation was secure. “Peter,” his brother says, “had nothing to lose.”

When Galbraith arrived in Kabul, in June 2009, the diplomats there were quietly optimistic. A first round of military reinforcements were arriving, Holbrooke was organizing things, and a presidential election was scheduled for the end of August. Everyone assumed that President Karzai’s reelection was a foregone conclusion. The point was the process. The West hoped to seed a democratic tradition in Afghanistan. “The consensus,” explains Tim Carney, a retired ambassador whom the State Department had appointed its point person on the election, “was that elections would do that.”

Galbraith arrived with a “flourish,” as one U.N. official put it, and changed the U.N. mission in the same way that McKinsey consultants transform small-town factories. There were now meetings where before there had been none and, quickly, a purpose. After Khost, Galbraith’s mind focused on the ghost polling stations. From the Afghan election staffers, he managed to wangle the fact that 1,200 polling stations would be set up in locations that could not be secured. Twelve hundred! He was amazed.

Galbraith met with the chief of staff of the Afghan army, who admitted that in the key Pashtun provinces, the army only held individual points. Galbraith pressed the top Afghan election officials to get rid of the ghost polling stations, making members of Karzai’s administration livid; he told Western diplomats that the election, and therefore the government, risked illegitimacy.

“Previously, the plan had been quiet private meetings to urge compliance,” says Cook, the U.N. election adviser. “But that wasn’t working, and it wasn’t working because the Afghans were thumbing their noses at it.”

The Obama administration, as it took over, had been far more leery of Karzai than the Bush White House had, and Galbraith shared the skepticism. Two days after he’d visited Khost, with Eide out of town, he went on his boss’s behalf to a meeting at Karzai’s palace, in a long room with ornate wood paneling. Galbraith relayed what he’d heard in Khost and said that there must be similar problems elsewhere. “Karzai is very theatrical, and his reaction was like Claude Rains in Casablanca—‘I’m shocked, shocked!’ ” remembers Carney, who was in the meeting. “But Karzai was taken aback. I think that rang some bells.” It proved to be the last meeting on election security that Karzai would hold. When Eide returned, according to Galbraith, he told his deputy “to stop. He said we’re not going to discuss polling centers again.”

Things between Eide and Galbraith were degenerating quickly. The two diplomats had known each other in the Balkans in the nineties; they had taken their families on a sailing trip in the Adriatic, and Eide had introduced Galbraith to the Norwegian policy analyst who is now his second wife. (“Though she never really liked him,” Galbraith says.) Now they were living together in Palace 7. Eide had become Karzai’s chief interlocutor with the West and saw him frequently. “Across the board, Kai Eide was trying to build a relationship with Karzai,” says Carney. “The question is, was Kai Eide sufficiently savvy to see when that effort became self-defeating?”

For a month, Galbraith and other Westerners had been pushing the Afghans to abandon the polling stations they couldn’t control, and each time the defense minister had insisted they would be able to control them by August 20, Election Day. They couldn’t. “It was obvious that night that it was massively fraudulent,” says Galbraith. “We had reports from U.N. staff on the ground of negligible turnout across the Pashtun areas. And we were getting vote totals—in Kandahar region, for instance—that would indicate in the city 30 percent turnout, in the suburbs 60 percent, in the outlying areas 200 percent.”

Galbraith did not then have access to the details, but when they emerged, they would prove him right. The paper ballots had been distributed in pads of 100; voters were meant to take a single detached ballot, mark their preference, fold it, and slip it through a slot into the ballot box. When the U.N.’s auditors went through the boxes, they found the pads intact, each ballot marked in the same handwriting, rubber bands wrapped around them. Polling station after polling station submitted exactly 500 ballots, with every single vote marked for Karzai.

Everyone had expected a Karzai landslide, but it now seemed that if the obviously fraudulent ballots were excluded, the sitting president would win just less than 50 percent of the vote, not enough to avoid a runoff.

On September 8, the Afghan election commission preliminarily announced that Karzai was the winner. It was Ramadan, and the American ambassador hosted an iftar dinner at sunset. Afterward, on the roof of the residence, the Afghan election commissioners told Galbraith and American ambassador Karl Eikenberry that even if there were to be a runoff, it would be impossible to hold before the following spring. If that was true, Galbraith said, then the country was facing “a constitutional crisis”—that Karzai was manipulating the situation to stay in power an extra year after his elected term had ended. Galbraith later suggested to Eide that the international community insist on a different interim president—perhaps, he said, the former finance minister Ashraf Ghani.

The next day, Eide went to see Karzai and, returning, visited Galbraith. “He made clear that he didn’t want to do anything about the election fraud,” Galbraith remembers. “He said we didn’t have a role here, our only job was to support the Afghan election commission in whatever they chose to do.”

Galbraith and Eide had two different conceptions of what diplomacy entailed in Kabul, each of them principled, in its own way. Eide wanted to support the fragile, flawed government because he saw in it the best hope for stability and progress. “I tried to prepare for a worst-case scenario where I had to deliver some very unpleasant messages to [President Karzai],” Eide says. “If you want the president to understand and accept what you are saying, you need a certain level of confidence. Peter wants to play the big role.” In Kabul, Galbraith tried “grand solutions that go beyond the rules of the game”—particularly the suggestion that Karzai be removed as interim president. “They may seem attractive, and to some they were attractive,” Eide continues. “But there would have been political riots if we were to follow these recommendations. It wouldn’t have worked.”

The feud became public. The Times of London editorialized in favor of Galbraith. “The question in the media became this feud between Kai and Peter, and that took the focus off the Afghans and the fraud,” says Cook, the U.N. election adviser. “Most of the international community felt Peter was being too vocal.” By this time, Galbraith had returned to the States. “There is,” Carney says, “the Peter who I admire greatly, and then there is Peter the butthead.”

By the middle of September, the Afghan election commission had officially declared Karzai president. The Americans and the U.N. insisted on a runoff, and one was scheduled, though the second round of elections would use exactly the same polling places. Then, shortly before the vote, Karzai’s opponent, Abdullah Abdullah, dropped out. The Americans recognized Karzai as president. The White House was moving toward its massive surge of troops and civilians, which would be announced in December, and the Americans had already begun to turn the page. Galbraith had hoped for some support for his case from his friends within the Obama administration. None came.

Galbraith lives, most of the time, fifteen miles northwest of Brattleboro, Vermont, in a spot where the cell-phone service, as he notes many times on the stump, is worse than it is in East Timor. He owns a renovated farmhouse high upslope of 100 acres of hillside, and from his porch you can see the pond in which he swims every day. The spot reminds you of the New England view that the nineteenth-century poets had—a violent, anarchic place, with Indians lurking. His father bought much of a nearby mountain in 1947, and the family has been coming here ever since; his brother Jamie’s place is just up the road. Galbraith gave me a gentleman naturalist’s tour of the area, getting briefly lost in the woods just after visiting the beaver dams and just before stooping over on the side of the road to notice a patch of bright-white mushrooms. “Fine puffballs,” he murmured, bending over to pick them.

Galbraith’s run for the State Senate has been a bit of a mystery to those close to him—both because it has come late in life and because the post, a part-time position, is so obscure. Two years ago, he considered running as the Democratic nominee for governor, challenging the popular Republican incumbent Jim Douglas, but he dropped the bid after he failed to persuade a progressive third-party candidate to abandon the race. “It was interesting to see the methodical way he went about mastering local issues,” Jamie Galbraith says. “He tried this once before and absolutely hated it. This time he stuck with it. We’ll see how he adjusts.”

“I still want to do useful things,” Peter Galbraith explains. He says he wants to help build in Vermont a publicly funded health-care system, for instance, as a model for the nation. But his policy ideas seem preliminary, and it’s hard to avoid the impression that even a fledgling political career is, for Galbraith, simply the best of the available options, and that his mind is still in Afghanistan.

The night before I left, Galbraith had his brother, a few friends, and me over for dinner. It was a boozy meal that started pleasantly and turned grim, when Galbraith and his assistant Tracey Brinson—who had accompanied him to Afghanistan and stayed there after he left—took turns telling what is for Galbraith the emblematic story of Afghanistan, which is the attack on the Bakhtar guesthouse.

Just before dawn on October 28, 2009, Galbraith said, after he’d left the country and a week before the scheduled runoff election, a group of Taliban fighters dressed as Afghan police arrived at the guesthouse in Kabul that housed U.N. election staff. They climbed a fence and began to lob grenades inside. Two security men—one a former U.S. Navy commando named Louis Maxwell—fought them off from the roof for the better part of an hour, permitting most of the U.N. staff to escape, though several were injured and eight people were killed. After the fight was over and the courtyard secured, Maxwell walked outside of the compound, where he was shot dead, likely by a member of the Afghan police.

The event was depressing in all aspects—the U.N. initially reported that Maxwell had been killed by Taliban, until a German magazine obtained a video of the incident. But to Galbraith it seemed to make plain the folly of a counterinsurgency strategy. “It is impossible to separate the Taliban and the government,” Galbraith said over dinner. “They are the same thing. Without a credibly elected government, there is no place for a tribal leader to go to rat out a Taliban commander. And so a counterinsurgency strategy has no hope.”

At the end of this year, while the U.N. is reviewing Galbraith’s wrongful-termination claim, President Obama will be conducting a review of the Afghanistan surge he authorized last fall. The administration is now spending billions of dollars to build an Afghan state—placing advisers in the ministries, recruiting and counseling judges, organizing and training an army, all the while partnering with a government it suspects is corrupt. To Galbraith, this is the same kind of strategy that failed the Bush administration in Iraq: a quasi-colonial insistence on holding together a country by will alone. And so another form of idealism had supplanted his own.

“You cannot impose on people your own wants,” Galbraith says vigorously, “no matter how much you yourself might want them.” He meant this as a policy lesson, but it is hard not to infer a second meaning, one he missed: that he himself could not impose on the West his own conviction that a principle was at stake, no matter how keenly he felt it.