Jeb Bush walks into the room wearing a shimmery sharkskin suit, taller than you expect and trimmer, grabbing hands and beaming like a man who’s running for something.

“Good to go,” he says, clapping impatiently. “It’s game time.”

Backstage at a theater in Tampa during the GOP convention, the former governor of Florida has shown up to discuss education policy after a screening of the new Maggie Gyllenhaal movie, Won’t Back Down, a drama about a single mother who does a hostile takeover of her failing public school and turns it around—a Jeb Bush fantasy come to life. But he’s got plenty on his mind besides education. Sitting down across from me, he assumes his role as party Cassandra, warning of the day when the Republicans’ failure to tap an exploding Hispanic population will cripple its chances at reclaiming power—starting in Texas, the family seat of the House of Bush.

“It’s a math question,” he tells me. “Four years from now, Texas is going to be a so-called blue state. Imagine Texas as a blue state, how hard it would be to carry the presidency or gain control of the Senate.”

Imagine. Four years from now.

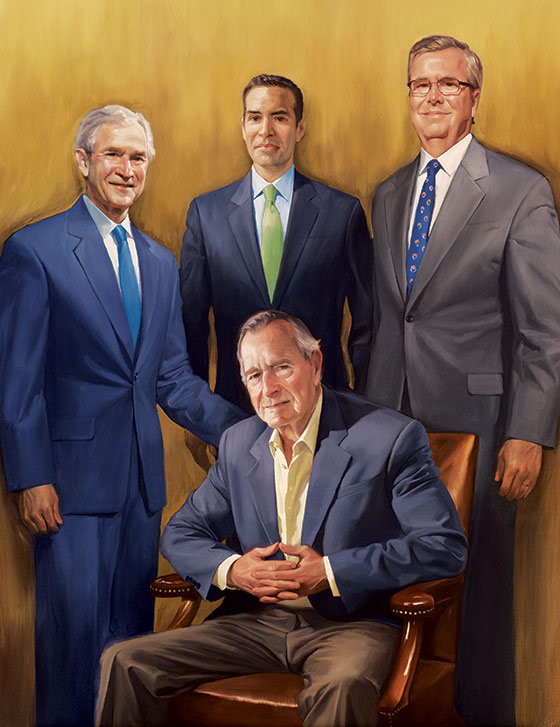

Once again, it is impossible to ignore Jeb Bush describing a problem he’s uniquely suited to solve for his party: a popular two-time governor of a Hispanic-heavy state, with a record of improving education for minorities, fluent in Spanish, married to a Latina, and father to two Hispanic sons, George P. Bush and Jeb Jr. By Jeb Bush’s own calculus, Jeb Bush would make a great presidential candidate.

But then there’s all that familiar DNA above the collar line: the identical head of hair as his brother George W., the 43rd president; the same aquiline nose, inherited from his mother, Barbara, whose downturned mouth and pronounced jowls Jeb also shares and which make his face a softer, squarer version of W.’s. From the 41st president, the father, the same close-set eyes; the Mount Rushmore–ready forehead; and the mild, patrician air of confidence, handed down to Jeb from Senator Prescott Bush of Greenwich, Connecticut, over 59 years ago.

For all his lightness of being, Jeb Bush carries a heavy burden. After eight years under the presidency of his older brother, the nation was more than ready to see the Bushes exit stage right, maybe forever. A majority of Americans still blame W. for the state of the economy, and pretending Bush disappeared from the face of the Earth has been critical to an attempted Republican Party makeover. Among Republicans in his home state, purified in the fires of the tea-party movement, Bush is persona non grata. “Imagine a world where George Bush is too liberal,” says Evan Smith, the editor-in-chief of the Texas Tribune. “That’s Texas 2012.”

Imagine.

But W.’s conspicuous absence—and his brother’s full schedule of TV interviews and panel discussions—signaled a careful reinvention, the first stage of a dynastic comeback. Jeb Bush’s shadow campaign began in June on the occasion of a hagiographic HBO documentary about the patriarch, titled 41, when Jeb emerged from a long silence and began publicly lamenting the state of the party by offering his father as the emblem of a once-functional politics gone extreme. It culminated with Jeb Bush—the wonkier and more introverted Bush—on the main stage of the GOP convention, before Mitt Romney’s speech, telling everyone to lay off his brother.

For many in his party and for most of this year, Jeb Bush was the ghost of what might have been. When Romney was spiraling downward, the party was in such dire straits, the thinking went, that the Bush political brand, as battered as it was, looked respectable again. “I believe the Bushes are true north,” says Mark McKinnon, the former aide to the 43rd president, “and we’ve got to get that back.”

For a party with clear fissures, Jeb Bush is an insurance policy against a Romney loss to Barack Obama. Many Republicans believe losing in November would create an epic struggle between the hard right of the party and the moderates who believe that to win, the GOP has to make a credible effort to court Hispanics. Jeb is the obvious leader of the moderate wing. The people in Jeb’s orbit have been supporting Romney, but with significant reservations because of the extreme positions Romney had to take to secure the nomination. One told me that nobody who decides to build an indoor elevator for their car can get elected in America. Even after the first debate, these people remain convinced a Romney loss is considerably more likely than not. “I don’t see how the math works for him right now,” says a close associate of Jeb’s.

*See Jeb Bush’s response to New York.

And should that happen, the answer in be 2016 may be a GOP nominee with the courage of his more centrist positions. In other words: Jeb. Even his own son, George P., acknowledges that his father’s declaration that 2012 was “probably my time” contains a significant caveat. “More than anyone, he knows that politics is about timing,” he says. “A lot of it hinges on what happens in November.”

Launching another Bush candidate in the next four (or eight) years would be a delicate operation. Jeb Bush has to not only tame internal divisions in his party but carefully work around the thorny legacy of his brother’s presidency—without seeming to distance himself from the family. The late Ted Kennedy famously said “the dream”—of his brothers—would “never die”; for Jeb, that’s precisely the problem. And he also has to resolve his own Hamlet-like impulses. Six years out of office, Jeb Bush seems to carry a certain torment as he ponders his future—a psychological problem that runs in dynasties.

But the gravitational pull of money and Bush-family Manifest Destiny—and, if Romney loses, party desperation—may be too great. As James A. Baker III, secretary of State under 41, the man who helped propel George H.W. Bush to power 40 years ago, tells me: If he were writing this story, “I would not conclude that we’re not going to ever see another Bush candidate.”

This past June, the Bush family and their closest friends converged on Walker’s Point, their compound in Kennebunkport, Maine, to celebrate the 88th birthday of the patriarch, President George Herbert Walker Bush. To herald the occasion, HBO had set up a screening of 41, which was produced by his longtime friend the producer Jerry Weintraub. At the dinner party afterward, there was a palpable sense that Bush was taking a final victory lap. Behind the scenes, the family was already making advance funeral arrangements and encouraging news outlets to prepare obituaries. Bound to a wheelchair and suffering from a Parkinson’s-like disorder, he smiled softly, easily brought to tears.

In the room were Brent Scowcroft, his old friend and former national-security adviser—and the 43rd president, his son George W. Bush. For some, the shadows of the family psychodrama were alive in the room. When W., whose controversial presidency had been a kind of rebuttal to his father’s, was asked to give an impromptu toast honoring the man he had both worshipped and sought to overcome his entire life, witnesses say he appeared pinched and unhappy, his toast perfunctory. “It was highly unemotional,” says an attendee.

For all his legendary swagger, W. shrank in the presence of his father, either out of deference or something else. Perhaps he merely resented the presence of the eastern elite he detested, people like Time Warner chief Jeff Bewkes and HBO CEO Richard Plepler. “It was a weird evening,” says the attendee. “He knew that the Time Warner executives were not his base, and so here he is in his house with the Hollywood ‘a-leet,’ as he calls them.

“He’s become increasingly agoraphobic,” this person adds of the former president. “He looked startled by the whole thing. But he doesn’t like people, he never did, he doesn’t now.”

Indeed, George W. Bush, now 66, has spent the past few years living as invisibly as possible, working diligently on his golf game at the Brook Hollow Golf Club in Dallas, showing up at a Rangers baseball game, or being spotted eating a steak in one of his favorite restaurants. While the rest of the world judges his years in office, he’s taken up painting, making portraits of dogs and arid Texas landscapes. “I find it stunning that he has the patience to sit and take instruction and paint,” says a former aide.

He gets a regular drip feed of political news from Karl Rove and others—he’s been critical of Romney’s campaign and skeptical of his chances. He meets once a month with the George W. Bush Institute at Southern Methodist University to review the latest policy projects and occasionally escapes to Africa, where this summer he led a delegation bringing attention to the epidemics of cervical cancer. There, he finds the adoration and respect he doesn’t often find outside Texas. The most unpopular president in recent political history, W. left a record of big-government spending and intractable wars that remains difficult even for allies to defend. In interviews, both Scowcroft and Baker struggled to praise Bush 41, the father, for his handling of the Gulf War without implicitly criticizing 43’s invasion and occupation of Iraq (“A somewhat different perspective on international relations,” says Scowcroft gingerly). Bush 43 had taken his father’s inheritance—including several members of his administration, like Colin Powell and Dick Cheney—and used them to dismantle his father’s legacy. But for all the foreign-policy issues, it was the collapse of the economy that left the biggest and most complex political aftermath for the Bushes. The Medicare prescription-drug-benefit bill in 2003, conceived by Bush strategist Karl Rove to capture Florida in the reelection, would add nearly $400 billion to the deficit, which the Bush administration would run over $10 trillion by January 2009. Bush’s authorization of the bailout of the big banks was the genesis of the groundswell that morphed into the tea party—making the Bush name the biggest liability to Republican power since Richard Nixon.

W. remains convinced history will vindicate him. But the Bush family is well aware of the damage to their future prospects. Perhaps none more than Jeb, the new custodian of the family brand. “Jeb is highly pained,” says a friend. “He is so loyal. Jeb knows some of the missteps, but Jeb is profoundly impacted by the kind of criticism he’s taken about his brother. It’s over the top.”

Of the five children of George H.W. and Barbara Bush—George W., Marvin, Jeb, Neil, and Doro—Jeb was the only one absent from the HBO screening. He had spent the previous week with the family in Maine, but left for New York before the celebration. On his father’s birthday, Jeb made big news from comments at a panel for the “a-leet” at Bloomberg LP, where he laid out a wholesale critique of the Republican Party—using his father as his political pole star. His father, he said, “would have a hard time” under the current Republican “orthodoxy,” which “doesn’t allow for disagreement, doesn’t allow for finding some common ground.

“Back to my dad’s time and Ronald Reagan’s time, they got a lot of stuff done with a lot of bipartisan support.”

If you took Jeb Bush at face value, it might look as if he were throwing in the towel on American politics. “Here’s what I heard him say,” says a former official in Bush 43’s White House. “ ‘Fuck this.’ That’s what I heard. ‘This has gotten crazy, and I don’t want any part of this.’ ”

But Jeb’s statements performed valuable political work. They instantly made him the reasonable man of the Republican Party, an Establishment shepherd in the political wilderness, a role that should come in handy if Romney loses. In studiously avoiding mention of George W. Bush, he stealthily edited the 43rd presidency from his proposed golden era of compromise, positioning the Bush-family brand as signifying the reconciliation and even-keeled temperament of his father rather than the sensationally polarized presidency of his brother.

For those paying attention, Jeb Bush’s comments were not out of left field. They were only the public articulation of a drumbeat that had begun when the tea party began its revolt against the Republican Party four years ago. In the 2010 Texas governor’s race, the Bushes had backed the campaign of Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison against Rick Perry but failed to counter Perry’s tea-party-powered campaign. And Barbara Bush, the family matriarch, dismissed tea-party heroine Sarah Palin with the stiletto comment that “she’s very happy in Alaska, and I hope she’ll stay there.”

“I have great sympathy with what Jeb said,” says Scowcroft, whose famous 2002 Wall Street Journal editorial against the invasion of Iraq became signal evidence of 41’s disapproval of 43’s war. “I’m a lifelong Republican, and I haven’t changed my views at all, but now I’m called a rino.”

“We judge our presidents by how much they get accomplished, how much they get through the Congress,” notes James Baker, “and that will require some element of working with the other side.”

Jeb has also been willing to buck hardened GOP dogma. In early June, he told the House Budget Committee during a hearing on economic growth that he could accept a theoretical debt-reduction deal in which taxes were raised by a dollar for every $10 of spending cuts. “Put me in, coach,” he said.

The Bush dynasty is based on an ideal of public service, and a set of highly specific blueprints about how to synergize success in the private sector with a political career—but a key pillar is Barbara Bush’s Rolodex. A long-suffering political spouse toughened by the tragic loss of a daughter to leukemia in 1953, “Bar,” as she’s called, organized her husband’s network of friends into a Christmas-card list that doubled as a donor file, the foundation for the family’s political network. That list was chock-full of the oil-and-energy-industry executives George H.W. Bush had met through his moneymaking venture, Zapata Petroleum, and it provided the resources for every race the father and sons would run for the next 40 years.

Today, that card list is a computer database in Houston controlled by Jean Becker, President H.W. Bush’s chief of staff. John Ellis, a Bush cousin, says that network is alive and well. “The network is huge,” he says, “and powerful. So if Mitt Romney loses the election, and Jeb decides he wants to run for president, instantly there’s $30 million in the bank, instantly there’s a network of friends and supporters.”

While the network sits moribund, awaiting a Bush candidate, W.’s legendary “brain” and political footman, Karl Rove, has virtually absconded with the Rolodex, using it to christen himself party boss and kingmaker of the GOP. The Rove-conceived American Crossroads super-pac network is populated with the same oilmen and real-estate tycoons who fueled the Bushes. For W.’s cause, Rove was a brilliant tactician, and he helped build the network. But the larger family has long looked askance at Rove—Jeb Bush and his parents, especially Bar, don’t trust him, according to several family associates.

The Bushes, explains a close family associate, “have use for you, they have use for me, they have use for Karl. There is always business being transacted. But in terms of what they think of his character, they think [Rove]’s a shithead.”

A Jeb Bush candidacy might be useful for both men. But conversely, Jeb Bush, says a former Bush 43 White House official, “is the only Republican candidate who could co-opt him and make him irrelevant. He’s at the mercy of what happens with Jeb.”

Privately, George W. Bush has expressed ambivalence about Jeb Bush’s running for president. “I’m not sure he likes it, the idea of Jeb running,” says an associate of the president who has talked to him about it.

It’s easy to see why. His brother might supplant his tenuous legacy. And in a campaign, Jeb would invariably be asked to account for W.’s failures. “He’s going to get a question that no other Republican has had to answer in his first interview,” this associate notes. “ ‘What is your brother’s biggest mistake?’ ”

In Bushworld, a powerful paternal and fraternal dynamic has driven the family. Both Jeb Bush and W. spent much of their adult lives competing for the favor of their father. The brotherly combat went back to childhood, when George would line up his brothers for mock executions. “When they were young, Jeb was somebody for George to torture,” John Ellis told the Bush-family biographer Peter Schweizer. “As a kid, George viewed him as a completely unnecessary addition to the family … I think that carried on for a long time.”

In high school, Jeb went through a short period of rebellion as a member of the Andover Socialist Club, smoking pot and wearing his hair long. But unlike W., he settled down just as quickly, meeting his wife, Columba, while on an exchange program in Mexico when he was 17. He got a degree in Latin American studies from the University of Texas, married Columba, and joined Texas Commerce Bank.

Nineteen eighty, the year H.W. first ran for the presidency, was the defining year for Jeb. He had quit his banking career to work full time for his dad, campaigning for him in Puerto Rico, where his Spanish helped his father win the primary.

After the Reagan-Bush ticket won the White House, Jeb moved from the family seat in Texas to make his way in Florida. The reason he left would define him politically and personally: His wife, Columba, known as Colu, had experienced racism among their white, Republican circles in Houston.

When I ask Bush about this, he acknowledges that it happened. “Subtle, subtle,” he says. “It’s very different now, very welcoming, very open, particularly the big open areas.”

Colu gave Jeb an ultimatum: They could either move back to Mexico or to Miami, where her sister lived. He was happy to leave, says a close associate, because “he didn’t want to be another Bush in Texas.”

The first rule of the Bush family has always been to get rich before entering politics, as 41 had done when he moved to Texas from Connecticut and made his millions. Jeb Bush established his financial independence by partnering on a new real-estate company with Armando Codina, a Cuban immigrant and millionaire entrepreneur who had befriended George H.W. Bush and worked on his 1980 campaign for president. Codina made Jeb his partner and renamed the business Codina Bush Group, giving him a 40 percent stake in the profits. By 1987, he was appointed the state’s secretary of Commerce.

As his brother floundered with booze and bad business deals, Jeb quickly surpassed W. on the ladder. But the turning point came in 1994, when Jeb Bush ran for governor of Florida. Around that time, George W. had been convinced by Karl Rove he could make a run at Texas governor Ann Richards. Both had their mother’s card file of donors and supporters to aid their campaigns, but Jeb had his parents’ enthusiastic favor. Bush 41 reportedly burst into tears while trying to describe what it meant to him that Jeb was running. And privately Barbara Bush yelled at W. for running at the same time, saying it would soak up contributions they needed for “Jebbie.”

But W. had a secret weapon in Rove, who had spent the past decade helping Republicans regain power in Texas by using special-interest pacs to aid key Republican races throughout the state. And the animating drive for W. was clear: to overcome the shadow of his father after years of falling short. As Election Day approached in 1994, W. told a friend not to “underestimate what you can learn from a failed presidency,” referring to his father, who had been beaten by Bill Clinton two years before.

Jeb was the clear favorite to win his race. But he was hit by a series of late-breaking robocalls by his Democratic opponent, incumbent governor Lawton Chiles, warning that Bush was a tax cheat and his running mate wanted to abolish Social Security.

The family was shocked when the family clown won his race and Jeb, the meticulous wonk, lost his. George H.W. and Barbara were inordinately disappointed for Jeb, and George injured W.’s feelings when he lamented Jeb’s loss in the same phone call he congratulated W. for his win. “Why do you feel bad about Jeb?” George W. was overheard to say. “Why don’t you feel good about me?”

Afterward H.W. told the press, “The joy is in Texas, but our hearts are in Florida.”

What Jeb didn’t have that W. did, of course, was a Karl Rove. “Jeb is smarter than George W. and has greater talent,” says a former White House official in 43’s administration who has worked closely with Jeb, “but he obviously suffers from those types of smart people who don’t delegate enough responsibility to others.”

The loss hit hard. Bush’s marriage to Columba hit a rocky patch, and during a period of searching, he converted to Catholicism.

Jeb regrouped, ran again in 1998, and won. Over the next eight years, he would become a popular two-term governor of Florida. But the 43rd president would overshadow him and redefine the family fault lines—between W. and his father and between W. and Jeb. In the infamous 2000 election between Bush and Al Gore, some in Bush 43’s camp blamed Jeb for failing to nail down Florida. Says the former White House official: “We all went rolling into Florida during the recount, and Jeb was giving everybody the brush-off, and ‘Back off,’ and ‘It’s fine.’ But it wasn’t fine.”

In the next eight years, George W. Bush’s transformation into a war president, and his invasion of Iraq, would blot out his father’s legacy. It would also inflict collateral damage on Jeb: As Jacob Weisberg wrote, Jeb’s older brother “had raced ahead and blown up the bridge behind him.”

Why didn’t Jeb Bush run for president in 2012?

In a Republican field as weak as any in the past 30 years, Bush might have easily mopped the floor with Mitt Romney.

But Jeb had virtually disappeared after he left office in 2007, studiously avoiding the national press. His first order of business was filling his coffers. He signed on as a consultant to Lehman Brothers. After Lehman’s collapse in 2008, he joined Barclays, which led to a lot of golf games with bankers in New York. Along the way, he trimmed down his weight, consulted continuously with donors and political consultants, and prepared himself for … what?

Friends and former advisers say Bush was torn over whether to run for Senate in Florida in 2010. He opted instead to support Marco Rubio for the seat. As 2012 approached, he seriously mulled the presidency. Donors and former aides urged him to consider. He was again torn. People close to Bush describe several factors that dissuaded him, including a desire to make more money. But the major reason was the unwillingness, or inability, of his wife to be a political partner. Columba Bush, long and awkward presence in the Bush family, speaks English haltingly and has rarely joined her husband on political stages. When Jeb became governor, she spent less time in the capital of Tallahassee than she did in their home near Miami, where the family, including Jeb, all spoke Spanish. Signs of trouble first emerged in 1999 when she went on a five-day Parisian shopping trip and bought $19,000 worth of clothes and jewelry and tried declaring only $500 at Customs (to hide the expenditures from her husband, she said). After the ensuing media debacle, she was kept out of sight. “My wife is not a public person,” Bush said at the time. “She is uncomfortable with the limelight, which is why I love her. I don’t want a political wife—I want someone who when I get home I can have a normal life with.”

But things were far from normal. In 2002, their daughter Noelle, then 24, was arrested for prescription fraud—the first of a series of problems that would continue beyond Jeb’s governorship. “The Noelle issue has taken an incredible toll on both of them,” says a friend in Florida.

But then there was the obvious: People simply weren’t prepared for another Bush in the White House. As Jeb negotiated the right wing of his party in a primary circus, the media hot lamps of a presidential race would be trained on his ailing father, his reclusive brother, his own troubled family. No matter the weakness in the Republican field; it would take more time for the House of Bush to get back in order.

A Romney loss, of course, would put the GOP in considerably more disarray than the Bush family. Jeb avoids characterizing the Republican Party today, instead looking to some unnamed future: “The GOP should be the GSP, the Grand Solutions Party,” he says. “It should be about solutions, not talking points. You look at the governors and you see the future of the party.”

James Baker says Jeb Bush could well be that governor—if he can contend with a post-Bush party: “I would suggest to you that if Obama is reelected, which—I hope it doesn’t happen, but if he’s reelected—I think Jeb might very well decide to do something in 2016. But, of course, he will have to get out there and put his hat in the ring and beat people like [Paul] Ryan and [Rick] Santorum.”

And there’s the rub: Can the Republican Party embrace a moderate again? Since leaving office, Jeb has become distinctly less conservative. In the past, he was a pro-gun, pro-life, pro–death penalty hard-liner who described himself as a “hang-’em-by-the-neck conservative.” But Jeb’s recent friendship with Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a critic of the tea party, has seemed to crystallize a shift toward a more moderate approach. In recent years, the two have become political allies, simpatico on education and immigration, and frequent golf partners in Florida and New York. Bush now serves on the board of directors at the Bloomberg Family Foundation, and Bloomberg L.P. hosted panel discussions at the GOP convention featuring both Jeb Bush and his son, George P. Bush.

“It’s the opposite of the reality show that was put on during the Republican primaries,” says Steve Schmidt, McCain’s campaign manager in 2008. “At a very serious time, when so much of the dialogue on the right has been frivolous and ludicrous, you have a person who is talking about the challenges of the time we live in.”

Jeb has already begun to test the balance between the demands of the tea party and the need to establish himself as a serious person. He has forcefully sponsored the career of Senator Marco Rubio in Florida, the Cuban-American tea-party superstar who serves as a kind of surrogate who can bolster Bush’s conservative credentials while also emphasizing his key talking point of capturing the Hispanic vote in 2016 and beyond. Jeb has also been careful about protecting his reputation for seriousness. In July, Bush attended a meeting at ultrasecret Bohemian Grove, the private California club where politicians and industrialists powwow in the woods once a year. Jeb was “greeted like a rock star,” according to the Florida donor who invited him. But when the Koch brothers, the financiers behind Americans for Prosperity, a nonprofit that has funded tea-party causes, invited Jeb Bush to their camp for lunch, Bush turned them down—for an education symposium.

Jeb, too, is setting himself up to be a uniter, not a divider. “Things ebb and flow,” he tells me in Tampa. “To be successful, we have to offer concrete solutions to problems rather than taking positions. And the party that figures out how to do that will gain the majorities.”

And he is clearly building something that looks like a platform. “We can tout our exceptionalism,” he says, “but our exceptionalism is increasingly not for everybody in the country, and it’s changing who we are as a nation, and it’s having an impact on all of us, not just the people lagging behind. Immigration is as much about the American experience and the values we share, and a lot more about economics than it is about politics.”

He certainly sounds like a man running for something. He also sounds like a very different Bush. “I use the analogy of Monty Python, the movie,” says Bush of the current GOP immigration problem, “where the guy is protecting the log across the little creek. ‘It’s just a flesh wound.’ We’re competing with ninjas, you know, guys with big, sharp knives, and we have no weapon, and we’re playing like we’re fighting them, and we get an arm cut off—‘Oh, it’s just a flesh wound’—and we’re down to the trunk.”

In truth, Jeb Bush may never return to politics, especially if issues surrounding his wife and daughter remain prohibitive. But there are more Bushes in the wings: Jeb’s own sons, George P. Bush and Jeb Jr., both of whom appeared in Tampa on panels. Jeb Jr. has been floated as a congressional candidate in Florida. And with his father’s guidance, George P., age 36, has been assembling pieces for a political run of his own—in Texas, 2014.

George P. Bush, whose grandfather famously referred to him and his siblings as “the little brown ones” in the eighties, says he cannot escape the family name, even though he tried at first. “It’s quintessentially Bush to establish your own identity,” he says, “but in the eyes of others it’s viewed as something larger than that in terms of having the name. I feel like I can kind of be myself, but embrace who I am as a Bush.” As is Bush custom, George P. has been establishing his fortune, first in private equity doing real-estate deals, and now investing in the energy sector—just like Grandpa. Like his grandfather, George H.W. Bush, he served in the Navy, doing a six-month tour in Afghanistan under a pseudonym to protect his security. He is head of pacs trying to draw young people and Hispanics into the party, and this August, he agreed to be the deputy finance chair of the Texas GOP—an echo of how his father entered into politics before running for office. Like his father, he has also thrown his support behind a Hispanic tea partyer—Ted Cruz, who is running for Senate in Texas this fall.

In his new role, George P. Bush is connecting with the big Texas donors, many of whom have been on his grandmother’s Christmas-card list since the sixties. “I learn more about my family on the campaign trail than I do in person,” he says.

“George P.’s future in Texas in unlimited,” says James Huffines, a Texas financier and GOP fund-raiser. “He’s the right age, he connects well with people, he has good political instincts, and he bucked the Establishment and got onboard with Ted Cruz.”

Jeb Bush says he’ll be there for his son. “If George P. decides to run for office someday, I will be the first to support him,” he tells me.

But perhaps ominously, Jeb’s son is also consulting with … his uncle George. “We’ve compared notes,” he says.

In recent conversations, W. evinced more enthusiasm about P.’s prospects than Jeb’s. He recently compared his nephew’s remarkable ability to transcend the racial divide between Hispanics and Caucasians to another successful biracial politician who got a lot of traction invoking the Bush name: Barack Obama.