One day early this August, Mitt Romney gripped a microphone at the Iowa State Fair, faced a crowd of a few hundred people, and began, a little joylessly and therefore a little rapidly, to give a speech. It is the opinion of some of Romney’s friends, some of the men with whom he made his fortune, that the repetitive business of campaigning simply bores him and that this boredom is responsible for the fairly sizable gap between the charismatic man they know in private and the battery-powered figure who often appears in public.

Romney, of course, is not the only person bored by Romney’s campaign appearances, and in the glazed reaction of the crowds you can see some skepticism about whether a candidacy predicated on bringing a businesslike efficiency to the WhiteHouse—a candidacy, basically, of process—could be something to rally around. “Over the coming decades,” Romney said at the fair, barely pausing between each idea, “to balance our budget and not spend more than we take in, we have to make sure that the promises we make in Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare are promises we can keep. And there are various ways of doing that. One is we could raise taxes on people …”

“Corporations!” a man cried out from the midst of the crowd. Romney was halfway through his next sentence, but he stopped and pivoted, noticing the hecklers, one of whom (it turned out) was a 71-year-old former Catholic priest from Des Moines. Morality incarnate. “Corporations!” a heckler cried again.

Romney grinned. “Corporations are people, my friend,” he said, neatly, flatly, and looked back to the crowd, eager to press on. Suddenly there were loud objections coming from all over, catcalls and cries of disbelief. But the cameras detected a splash of interest on Romney’s face.

“Of course they are,” Romney said, and he began to explain his logic. “Everything corporations earn ultimately goes to people. So—” Another heckler started ostentatiously laughing, a kind of mock disbelief. The candidate tried another tack. “Where do you think it goes?” Romney said. “In their pockets!” someone cried out.

Romney was already a step ahead. “Whose pockets?” he said, now almost gleeful. “Whose pockets? People’s pockets! Okay. Human beings, my friend!”

In his quick, casual reply—corporations are people—Romney had seemed to give something away, though it wasn’t immediately clear what. The press chose to play the episode as a “gaffe,” as ABC’s Jake Tapper described it, a moment in which the weakness in Romney’s political pitch, the gap between his own privileged experience of the world and that of working-class voters, had been exposed. MSNBC, in a spate of giddy incredulity, seemed to keep the clip on loop for a week. But Romney’s own campaign managers did not try to obscure the episode at the state fair, to say he had been misunderstood or to secret it away. Instead they promoted it, as an advertisement of principle, and made the confrontation the centerpiece of a solicitation to supporters. A few days later, Romney’s communication director, Gail Gitcho, told the press that the exchange had raised $25,000 within 24 hours.

The incident, in retrospect, did less to peg Romney as a creature of privilege than it did to reveal something deeper. For Romney, the corporation has long been an object of a certain idealism. It is something he has spent much of his adult life—first as a management-strategy consultant, then as CEO of the private-equity firm Bain Capital—working to perfect, to strip of its inefficiencies until it might function as a perfectly frictionless economic unit.

The political genuflection to businessmen is so gauzy and generic that praise for a candidate’s private-sector acumen can often sound phony. But Mitt Romney is the real thing. He was, by any measure, an astonishingly successful businessman, one who spent his career explaining how business might operate better, and who leveraged his own mind into a personal fortune worth as much as $250 million. But much more significantly, Romney was also a business revolutionary. Our economy went through a remarkable shift during the eighties as Wall Street reclaimed control of American business and sought to remake it in its own image. Romney developed one of the tools that made this possible, pioneering the use of takeovers to change the way a business functioned, remaking it in the name of efficiency. “Whatever you think of his politics, you have to give him credit,” says Steven Kaplan, a professor of finance and entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago. “He came up with a model that was very successful and very innovative and that now everybody uses.”

The protests going on at Zuccotti Park now have raised the question of whether that transition was worth it. What emerged from that long decade of change was a system that is more productive, nimble, and efficient than the one it replaced; it is also less equal, less stable, and more brutal. These evolutions were not inevitable. They were the result, in part, of particular innovations developed by a few businessmen beginning a quarter century ago. Now one of them has a good chance of becoming president.

Right now, a decade into the 21st century, the character of the management consultant is so ubiquitous a part of the global economy that McKinsey more or less guards the gate of the modern financial world. There is a study currently concluding in India, for instance, in which Accenture consultants are parachuted in to village textile factories, while a control group of factories is being kept virtually consultant-free, to see how much the strategists can improve operations. (The early results look good for the consultants.)

But in 1975, when Mitt Romney graduated in the top 5 percent of his Harvard Business School class, consulting was still a novel field. As Walter Kiechel’s entertaining history The Lords of Strategy documents, the three most prestigious consultancies (then, as now, McKinsey, the Boston Consulting Group, and Bain & Company) believed they were bringing a newly sophisticated, quantitative approach to business, using theories and techniques to help American industry modernize. They regarded themselves as intellectuals, and they also paid better than anyone else—this being a decade before Wall Street salaries started to really climb—and so Romney made what was, at the time, an obvious career choice. He became a consultant, first at the Boston Consulting Group and then, three years later, at Bain & Company.

The Bain & Company consultants who traveled the circuit of American business in the late seventies and early eighties experienced a mass of frustrations. The efficient, data-driven theory of business the consultancies had developed did not in any real way cohere with the practice of business that they saw in executive suites in St. Louis, Rochester, Houston. The theory said that companies should focus on their core business, but everywhere corporations were developing misguided plans to become conglomerates. The theory said management should measure everyone’s productivity in a firm, down to the lowliest employee, and every last worker should be rewarded or punished depending upon his performance, but the social relationships of business seemed to have decayed into a long, amicable golf-course lunch. There was a loyal, almost paternalistic attitude toward workers, protecting them even when they seemed to be drags on growth. When I interviewed Romney’s early colleagues about the business world that they surveyed during this period, they tended to adopt an attitude of high disdain. “Sloppy,” one told me. “Complacent,” said another. “Lazy,” said a third, “and out of tune with the change that was going on in the world.”

These men are still around—it is an unusually small and tight group, and many of them have continued to work on and off for Romney as he has moved into public life. They are mostly immensely rich, and if they give a collective impression, it is tanned, engaged, upbeat, as if it is always 8 a.m. on a Saturday and they are the fathers of shortstops. But when they began their careers, in their own telling, they were outsiders on the make. “If you think about that era—I grew up in the sixties and seventies—business wasn’t a particularly noble profession,” Geoffrey Rehnert, an early Bain partner, told me. “The best brains went into medicine, the next best went into law.” American business, he said, “had a thinner bench.” Those who gravitated to Bain built a culture that was “not entitled at all. Not a single person was born with money in their family. Every single person came from a blue-collar or middle-class background.”

“Except for Mitt,” I said. (Romney’s father had been the head of American Motors Corporation, the governor of Michigan, and a member of the Nixon cabinet; there is no credible way to describe the American elite that excludes Mitt Romney.)

“Even he didn’t come from affluence,” Rehnert insisted. “He wasn’t a trust-fund guy.”

Perhaps what he meant was: Romney wasn’t a Wasp. He never really talked to his co-workers about his Mormonism, but he sometimes joked with Jewish colleagues about how their religions made them all outsiders. Even for those who worked with him, Romney had an inscrutable quality: They never cursed around him and didn’t drink, and they understood that his social life would be his family life. “I always felt that Mitt viewed himself as one of the chosen few,” one of Romney’s colleagues at Bain Capital told me. “I don’t think it ever affected his decision-making, but there was that overhang.” Romney was, in the late seventies and early eighties, heavily involved in Bain’s recruiting, and this is how many of his cohort still view him, as a handsome guy with a great handshake. Bill Bain, the consultancy’s titular founder, once told the New York Times that Romney seemed a decade older than he actually was.

Of all the business theories developing at the time, Romney and his cohort were particularly influenced by one that played to their sense of detachment from the business Establishment. In 1976, two business scholars, Harvard’s Michael Jensen and the University of Rochester’s William Meckling, published an important paper elaborating a new idea of the firm, one that would come to be called “agency theory.” Previous corporate theory had emphasized a separation of powers between shareholders (who own a company) and management (the executives who run it). This situation, Jensen and Meckling pointed out, introduces a “principal-agent” problem, in which each agent has incentives that run contrary to the shareholders’ interests and could hamper the firm’s ability to function.

If you were looking across the landscape of American business 30 years ago, you could see agency problems everywhere. In the sixties, companies had become conglomerates so frequently that 20 percent of the Fortune 500 underwent a merger or an acquisition in a three-year period. CEOs had enjoyed building empires, and their shareholders, satisfied by decent returns, had often deferred to management control. But during the stagnant seventies, CEOs seemed loath to close factories and lay off workers. By the early eighties, as growth once again seemed possible, shareholders had become more restive, and innovative thinkers on Wall Street had begun to press the case that these companies had grown inefficient and timid, that management was underperforming.

Bain consultants did what they could, during their assignments, to improve their clients’ operations, but they were often frustrated by an agent problem of their own: Bain was just a consulting firm, and “a consulting firm,” says David Dominik, an early Romney colleague, “can’t make anything happen.” But Jensen and Meckling had sketched out one potential solution: If managers could secure financing to run their own companies, they might be able to build a better corporation, one that delivered stronger returns to its owners.

You could view this idea at least two different ways. One was as a chance to change the way American business is run. Another was as a business opportunity to exploit. Romney saw both.

Every business story begins with a proposition, and the one that launched Bain Capital was the notion that the partners might do better if they stopped simply advising companies and starting buying and running the firms themselves. When Bill Bain asked Romney to run the new spinoff, in 1983, the idea made sense from the perspective of Bain & Company. The senior partners were awash in cash that they were looking to invest; its more junior partners needed something to do. The original plan was vague in the details, but a bowl was soon passed around the Bain & Company boardroom so each partner could write his first name and the amount he wanted to invest on a scrap of paper and slip it in. Romney’s reputation was strong enough that he picked up $12 million in pledges in that meeting alone.

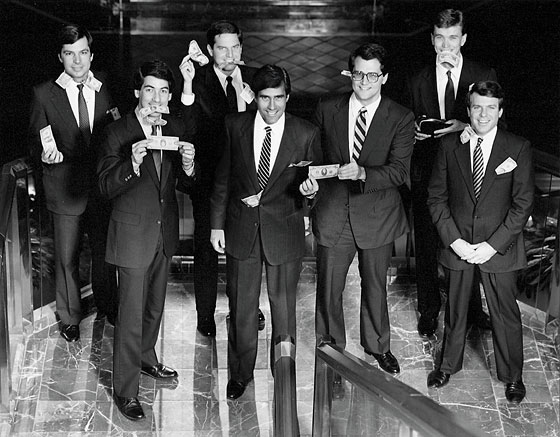

Finding outside investors wasn’t as easy. Romney went on the road, traveling to meet with billionaire families—an investment arm of the Rockefeller fortune, a Rothschild heir—arguing that Bain’s work in consultancy had prepared them to turn businesses around themselves. But Romney and his cohort were young men in their thirties with no experience investing money or running companies, and for nearly a year the pitch kept failing. Romney finally found some takers from Latin America, most important the enormously wealthy Poma family, and by 1984, he and six consultants he’d picked were staging a photo shoot for the brochure accompanying their first fund; grinning and geeky, they posed for an outtake with dollar bills stuffed in their mouths, their sleeves, their collars.

The leveraged-buyout industry in its early days functioned as a laboratory for reinventing business. Most of the promising firms were based in New York and specialized in financial innovation—reengineering a balance sheet or making use of new tools like junk bonds. Romney’s team in Boston looked down on them as “just deal guys,” and at financial engineering as a “commodity product.” Bain Capital focused instead on the way a business runs.

Their new firm reflected some aspects of Romney’s own personality: his mania for detail and for process. He was a cautious executive. “Mitt was always worried that things weren’t going to work out—he never took big risks,” one of his colleagues told me. “Everything was very measurable. I think Mitt had a tremendous amount of insecurity and fear of failure.” Romney never worked from any particular “macro theme,” any philosophy of how the economy was moving. What he employed instead was an exhausting habit of playing devil’s advocate, proposing sequential objections to a particular project or idea, until eventually, through a kind of Darwinian process, consensus was reached. “I never viewed Mitt as very decisive,” says one of his Bain Capital colleagues. “The idea was that if there’s enough argument around an issue by bright people, ultimately the data will prevail.” Romney may have been, as another early Bain Capital partner puts it, a “very case-by-case, reactive thinker,” but he was also an extremely hard worker and an egalitarian boss. He inspired intense loyalty, and there are still members of his circle who describe him as a perfect CEO. He was prone to profuse sweating, and the imagery of the era is heavy on the CEO’s drenched, stained shirts.

In the mid-eighties, a European retail outfit called Makro, a kind of continental Costco, was looking for an executive to help run its U.S. business, and it called a Boston supermarket executive named Tom Stemberg, inviting him to tour a pilot store outside of Philadelphia. The store didn’t impress him much, but he noticed that the office-supply aisle was absolutely packed with shoppers. He told the Makro executives to abandon their model and concentrate solely on office supplies; when they declined, he decided to give it a try himself. Boston business is a small world, and when he went looking for a venture-capital partner, he eventually found his way to Mitt Romney and his new $37 million fund. “Most V.C.’s thought it was ridiculous,” Stemberg says. “Mitt was highly unusual in that he went to the research level to study it.”

The trouble with the idea, to Romney’s subordinates at Bain Capital, was that the small businesses Stemberg needed to draw weren’t accustomed to visiting a store for office supplies; they got them from separate vendors, some who delivered—one supplier for pens and paper, one for printer cartridges, and so on. “Some of us were worried that we needed to change consumer behavior,” recalls Robert F. White, one of the firm’s managing directors. Romney persisted. As members of the group surveyed more and more small businesses in suburban Massachusetts, they discovered that if you asked a small-business manager how much he spent on office supplies, he would give you a low estimate and tell you it wasn’t worth it to send someone in a car to buy them. But if you asked the bookkeepers, you got a far higher number, about five times as much—high enough, Romney and Stemberg thought, to get them to come to the store. The idea became Staples. Romney’s Bain Capital colleagues were soon helping to select a cheaper, more efficient computer system for the first store; they were helping stock the shelves themselves. As Staples succeeded, and began to expand, they looked at analytics for everything—the small-business population around a proposed store site, traffic flow—and gamed out exactly how big a customer would need to be before it demanded delivery. Romney sat on the Staples board for years, and his company made nearly seven times what it invested in the start-up.

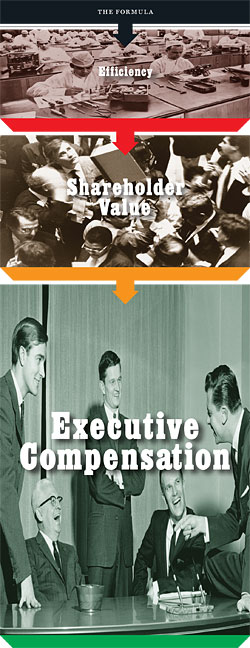

“These Bain Capital guys were agents of the shareholder-value revolution.”

Romney and his team did this sort of thing again and again, sometimes in venture-capital deals but more often through buyouts—Brookstone, Domino’s, Sealy, Duane Reade. In their more complex deals, they couldn’t rely on their own team to seek out every inefficiency. They needed a more powerful lever, and they turned to the solution Jensen and Meckling had begun to explore a decade earlier: offering CEOs large equity stakes in the company in the form of stock or stock options. This was a relatively new idea, mostly untried in American business. At the same time, a board formed in part of Bain Capital appointees who had put up their own money in the deal would be more engaged in management details. “You have the total alignment of incentives of ownership, board, and management—everyone’s incentives are aligned around building shareholder value,” Dominik says. “It really is that simple.”

In 1986, Bain Capital bought a struggling division of Firestone that made truck wheels and rims and renamed it Accuride. Bain took a group of managers whose previous average income had been below $100,000 and gave them performance incentives. This type and degree of management compensation was also unusual, but here it led to startling results: According to an account written by a Bain & Company fellow, the managers quickly helped to reorganize two plants, consolidating operations—which meant, inevitably, the shedding of unproductive labor—and when the company grew in efficiency, these managers made $18 million in shared earnings. The equation was simple: The men who increased the worth of the corporation deserved a bigger and bigger percentage of its spoils. In less than two years, when Bain Capital sold the company, it had turned an initial $5 million investment into a $121 million return.

Even by the standards of the times, Bain Capital grew tremendously fast: from $37 million under management in 1984 to $500 million in 1994 (and $65 billion today). To other businesses, the buyout industry both presented a model for better profits and posed a take-over threat. “Having the private-equity guys out there disciplined other companies,” says Nick Bloom, a Stanford economist. Some techniques developed in the buyout laboratory spread. Productive workers and managers were rewarded, while unproductive ones were cut loose. Corporations realigned themselves to deliver more value to their shareholders, increasing dividend payments and stock buybacks. Within a decade, ordinary businesses were giving large stock and option packages to CEOs. Executive compensation soared. “These Bain Capital guys,” says Neil Fligstein, an economics-sociology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, “were agents of the shareholder value revolution.” By the mid-nineties, The Business Roundtable had changed its definition of the role of a company, winnowing a broad set of responsibilities down to a single one: increasing shareholder value.

In October 1994, a machine operator named Harold Kellogg gathered five of his colleagues; borrowed a brown van from a used-car dealership in Marion, Indiana; and began to drive east on I-90, headed for Boston, where Romney, in his first political race, had suddenly begun to threaten Ted Kennedy. Kellogg had worked, for eleven years, for an office-supplies manufacturer called SCM, but a few months earlier his plant had been acquired by a Texas-based company called American Pad and Paper, in which Bain Capital had a majority stake. AmPad fired all of the union workers at Kellogg’s plant, more than 250 people in total, then hired most of them back at much lower wages; for years, they had gotten health-care coverage as part of their pay package, but now AmPad asked them to pay half of the costs. The whole plant walked out.

The narrative that the Kennedy campaign had been trying to build through the summer was that Romney was a Gordon Gekko type, but it didn’t really catch until Kellogg and his five friends started touring Massachusetts, visiting manufacturing plants, and then confronted Romney during an appearance at an East Boston Columbus Day parade. Kennedy’s campaign commercials were suddenly filled with flat midwestern accents. Romney promised, tepidly, to meet with the Indianans, “to see if there’s anything I can do.” Kennedy held on, and the line among political consultants was that the Kellogg stunt had helped turn the election.

It didn’t do much to help Kellogg. The plant in Marion closed down six months later, and the machine operator went to work at a nearby glass company. Management sent in Pinkerton guards and, according to a union source, took away machinery and moved it to nonunion plants in Utah and Massachusetts. “You had an industry where the only thing they did was converting paper to make Siegel pads, notebooks, and copy paper,” says Marc Wolpow, who was at the time the Bain Capital partner who worked on the AmPad deal. Labor in the plants, he says, was nearly a commodity product—the only thing Kellogg and his co-workers did was to move paper from one machine to another. This could be done more cheaply at plants in China or Indonesia. “Those jobs were going to get destroyed internationally. That plant was going to go out of business, and there was nothing Mitt should have done, or could have done, to prevent it.” But it is harder to be so charitable when you look at the broader moral contours of the arrangement. By 2001, five years after the company had been taken public, it had filed for bankruptcy and liquidated its assets. But Bain Capital made more than $100 million from AmPad for itself and its investors.

After the plant closed, the head of its union, Randy Johnson, tried to keep track of where everyone went. He assembled a roster of the destinations of his former colleagues—some moved to Tennessee, some to Texas—but the effort was incomplete, and what Johnson compiled was only a partial catalogue of loss. It’s difficult to track the fallout of any one private-equity firm’s work, but scholars have been able to look at the conesquences of the industry as a whole. These studies have consistently found that private-equity takeovers improve productivity and shed jobs. But one interesting nineties study, by two academics, Don Siegel at SUNY Stony Brook and Frank Lichtenberg at Columbia, found something surprising: White-collar workers, for the first time, were more vulnerable than blue-collar workers. “Part of what the private-equity firms were doing was replacing office workers with information technology—that’s where they were getting some of their gains,” says Siegel, now the dean of the University of Albany’s business school.

Here, too, private equity seemed to provide an early warning of broader changes. In three years during the early nineties, the Princeton economist Henry Farber has found, roughly 10 percent of American white-collar male managers lost their jobs. For the first time, according to data collected through the General Social Survey, white-collar workers were nearly as worried about losing their jobs as blue-collar workers. Those white-collar workers who kept their jobs worked harder, and the compensation that had once been spread through the broader middle ranks of corporations now collected at the top. In 1980, a CEO had earned about 35 times the wages of an average worker; by 1990, it was about 80; and by 2000, it was about 300. The portion of America’s gross national product that ended up in the hands of workers declined by more than 10 percent between 1979 and 1996; the portion that went to investors rose by a similar amount. “What you end up with is a choice between a bigger cake less equally split and a smaller cake equally split,” says Bloom, the Stanford economist. “But that’s a social question.”

There is no doubt that the tools of this efficiency movement helped to build the economy of the nineties, and this fact makes Bloom’s social question somewhat more complicated. That booming decade, with unemployment declining by 3.5 percent and real GDP growing by nearly 4 percent each year during the Clinton administration, depended heavily on a spike in productivity, which itself had hinged on the wide deployment of computer technology to displace more expensive forms of labor. Economists believe there was a clear connection between the labor-market changes in the early nineties and the great profits that soon followed. “Could we have had the productivity boom without displacement? My answer would be no,” says Frank Levy, an MIT economist.

The trouble, Levy believes, was that this new shareholder-value-driven system had no built-in mechanism of regulation, and its incentives geared CEOs toward shortsightedness and recklessness. “Any profit-making organization was going to take advantage of the opportunities to lower costs and become more efficient by taking advantage of foreign producers and installing technology, both of which meant losing jobs,” he says. “But decision-makers fully exploited at every turn the market power that they had. The question is, why were we so willing to exploit everything?”

The obvious answer is financial reward. But there may have been a cultural component, too. By the time Mitt Romney left Bain Capital for good, in 1999, American CEOs looked very different from the predecessors he had met in the seventies—the genial paternalists, spending their careers at a single company. More and more, they were pure meritocrats—well-educated, well-compensated, moving frequently between jobs and industries, trained to look ruthlessly for efficiency everywhere. They look a great deal more, in other words, like Mitt Romney.

If you trace the public controversies over Bain Capital over time, you can see how the obsession over shareholder value and efficiency proved not just inequitable but destabilizing. A half-decade after Harold Kellogg showed up in Boston, Bain Capital and others were sued by shareholders of Stage Stores, a Texas retailer, charging Bain of helping to manipulate the stock. The lawsuit accused the company of giving misleadingly optimistic performance projections, which sent the retailer’s stock soaring past $50 a share, at which point Bain Capital unloaded virtually all of its stock. When more realistic earnings projections were released, Stage Store’s stock plunged 58 percent in a single day. The lawsuit was later dismissed. But then, shortly after Romney left came the KB Toys fiasco, in which, another lawsuit alleged, Bain Capital and KB executives took a dividend recap of over $120 million two years before the company collapsed into bankruptcy.

No court found that Bain Capital did anything illegal in these cases. But these episodes still give a glimpse of the evolving problems of the shareholder-value model, and some consequences of the trade-off we made of stability for growth. In some economic moments, a program of radical efficiency can be good for society; at other times, when there is less fat to trim, the same instincts can lead a company to cannibalize itself. “We’re living in a crueler capitalism,” Fligstein says. By some measures, he adds, “we’ve gone really quite a long ways. And nobody really knows what the tipping point is, or how you go back.”

When Romney was elected governor of Massachusetts in 2002, one of the members of his transition team was Tom Stemberg, the founder of Staples. The two men were talking one day, and Romney asked Stemberg if he had any ideas for how he ought to govern. Stemberg, thinking off the top of his head, had two ideas. “One was to blow up Logan airport and start over.” That didn’t make it far. The other one did.

Stemberg served then (as now) on the president’s council of Massachusetts General Hospital, and he remembered a conversation he’d had with a doctor named Peter Slavin, who has been the chief executive of that hospital system for most of the last decade. “[Slavin] mentioned this huge problem,” Stemberg told me, “which is all these uninsured people clog the ER.” The hospital had to treat them. “There was a law that said that all the insurance companies had to fund the free care. That system made absolutely no sense. “It was, as Stemberg told Romney, “the least efficient way to serve them.” The conversation moved on, and Stemberg figured his ten-minute-long career as a policy maven was over. “I figured that’s the end of that.” But Romney’s staffers, consulting with experts, began to work out a fix, requiring almost every citizen in the state to carry insurance, and providing subsidies for those who couldn’t afford it. Eventually he was heading down to Ted Kennedy’s office in Washington to explain the program, PowerPoints in hand. Three and a half years later, Romney introduced his universal-health-care plan, and in the press he credited Stemberg with suggesting it.

The punch line, of course—the punch line to Romney’s campaign so far—is that the plan he built was an almost exact model for Obama’s national plan, designed by some of the same experts.

But what separates Romney’s plan from Obama’s—and gives some clues about his potential presidency—is its almost-accidental origin. Romney did not begin with a philosophical quest to improve American health care. He began with the idea of himself as a problem solver and asked those around him for a problem that he might usefully solve. I remembered, when I was told this story, an anecdote I’d heard from a former political staffer of Romney’s. On even basic philosophical questions like abortion, the staffer said, Romney did not try to resolve the question in the abstract, as a matter of principle, and would consider instead various hypothetical cases—for instance, a late-term abortion—and build from them a politics. The line that Romney is a flip-flopper may vastly understate the depth of the condition.

It is arresting to imagine a Romney White House, inevitably filled with as many former Bain colleagues as each of his other public ventures have been: The PowerPoints, the 80-20 jargon, the clinical separation of decision-making from ideology, the detachment of those decisions from moral consequence, a persistent blind spot for people as people. It would represent the final ascension of a perfectly American type, one that has already remade the culture of business. I once asked a Bain colleague of Romney’s how Romney thought of his own core competence. “I think Mitt thinks he’s good at being Mitt Romney,” the colleague said.

But Romney’s career-long commitment to his own particular brand of impersonal decision-making might suggest something personal after all. One great mystery about Romney has been where his Mormonism comes in and what it explains. Maybe the clearest answer comes from taking at their word the businessmen with whom he came up, who say they never saw its influence. Romney’s religion constitutes a minority set of beliefs. Poorly understood and widely mocked, it can provoke suspicions about his motives. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that he has adopted a public persona that contains no detectable motives at all, one that is buried in objectivity, in data, in process. The best evidence of how important Romney’s religion is to him could be how far he has kept it from view. But the character that remains visible is at once uniquely American and a little strange: a perfectly objective efficiency machine.