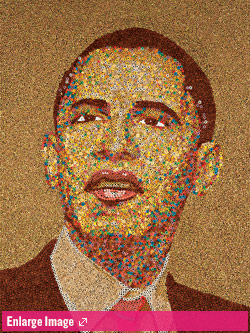

Breakfast of Champion by Ryan Alexiev and Hank Willis Thomas

During his proverbial hundred days, Barack Obama played the hand he was dealt. Not since FDR had a president entered office with so many messes that had to be sorted out yesterday. As Bill Galston—political philosopher, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and one of the intellectual architects of Clintonism—put it, Obama took office tackling not just one agenda, the way they usually do, but two: “the agenda on which he campaigned and the agenda that events forced on him.”

Obama’s first actions—the stimulus bill, Timothy Geithner’s bank plan, the stabilization of GM and Chrysler—were all about the forced agenda: de-jitter the markets (the Dow is up modestly since the day he took office), and restore some measure of public confidence (so far so good, say the “right direction–wrong direction” polls).

Now comes the hard part, what he’s been saving his ammunition for. Obama’s second hundred days are much more important than the first. Now the president is pushing his agenda. And push is the word. Almost every day, there’s something: the credit-card bill, the call to overhaul regulation of derivatives, the deal on auto emissions … in normal times, any one of these (especially that last one, which Congress had failed to pull off for 30 years) would have been thought a huge deal.

But in the present context, they’re only the appetizers. The really grandiose stuff is coming toward us right now, and the moment is dramatic. What’s remarkable about it is that Democrats in Washington don’t merely hope that by September we’ll have a health-care bill and that climate-change legislation will be accomplished by November. The Obamans, with a confidence that borders on arrogance, expect it. The deals are being cut on the Hill right now. Summer, typically a lugubrious interlude in these parts, when lawmakers go home and lobbyists flee to Bethany Beach (our mini-Hamptons, and yes, go ahead and laugh), will this year find the BlackBerrys and iPhones blinking and buzzing ferociously as the theoretical trillions flit in and out of in-boxes and find their final resting place.

Lawmaking is never a pretty affair, but under these circumstances—an obdurate GOP, a shaky economy, some nervous red-state Democrats, liberals in full but-this-is-our-time regalia—it could get especially nasty. Summer will be no Summer of Love. Remember, push is the word. It’s the Summer of Shove.

On climate change, an important moment arrived in mid-May, when California’s Henry Waxman, the saber-wielding chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee, shook hands with Rick Boucher of Virginia, a key coal-state Democrat, on emissions targets. And there’s a big climate-change conference in Copenhagen in December (Copenhagen will replace Kyoto in our lexicon), and The White House would surely like its delegation to arrive with a legislative package in hand. Hence November.

Health care is a bigger challenge. Teddy Roosevelt tried it out. Franklin proposed it. Then Harry Truman introduced it. Beaten, every one of them. LBJ wanted a universal-coverage system but settled for Medicare and Medicaid. Teddy Kennedy and others have been trying ever since. And, of course, there was that little situation back in 1993–94.

The Clinton failure looms large. It took health-care reform off the table for years. But the defeat carried this paradoxical silver lining: It forced every Democratic presidential candidate after Bill Clinton to draw up and promote a serious health-care plan. You will recall Hillary and Obama, during their endless debates last spring, getting awfully wonkorific on questions like the individual mandate. So Clinton’s loss—and the continuing crisis, as costs and the number of un- and underinsured have exploded—made the party more serious. “The landscape is dramatically different on health care today,” says the Democratic Leadership Council’s Bruce Reed, who was Clinton’s domestic-policy adviser at the time, “in part because of the experience of ’94.”

The things Obama learned from that experience had to do not with substance but with, as we say down here, “process.” First, he’s letting Congress take the lead here. The Clintons wrote a bill and told Congress to pass it. Congress famously bridled at this (recall Pat Moynihan’s irritation with Hillary, later patched up). The Obama White House’s thinking is, Let our friends in Congress do it; if it’s under their authorship, they’ll be more invested in its passage. Remember Mencken’s famous dictum that no one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public? The Washington version is that no one ever lost political capital overestimating the egos of legislators. Especially senators.

Second, the Obama people remember how Clinton was dragged to the left in his first days in office with “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” The occupants of this White House are having none of that.

Third, Obama was smart to get the insurance and health-care CEOs to stand with him at that press conference on May 11. Obama certainly is not naïve enough to think this means they’re 100 percent behind him. But it does mean they’re playing ball. “In the business community, they assume health care is passing,” says Stan Greenberg, the Democratic pollster and analyst. “There will be a bill-writing table, and they want to be at it.” That, too, is a world away from ’94.

The White House wants a bill that will insure about 30 million more people than are currently covered (leaving about 17 million still uninsured); that will, for the already insured, theoretically reduce costs by bringing more people into the system and creating more competition; and that will end denials of coverage owing to expense and preexisting conditions for those with major illnesses.

The main points of contention will be two. The first, naturally, is cost. Two weeks ago, a Congressional Budget Office preliminary estimate pegged it at $1 trillion over ten years—that’s actually revised downward from an earlier preliminary estimate of $1.5 trillion. But it’s still real money. So where’s the revenue coming from?

Academics have been digging into this problem for years. The easy things, like higher sin taxes on cigarettes and booze, yield a few billion, no more. The administration is looking for revenue from other sources, like the recently announced plan to limit offshore tax havens.

But really, there’s only one way to raise revenue, and that’s to collect it. We know this as “taxes.” Here’s what’s kicking around the Hill now. Currently, if you have employer-sponsored insurance as most insured Americans do, it is untaxed. So they’re talking about taxing it. But for whom and at what rate?

Taxing all plans would obviously bring in the most revenue, at least $2 trillion over the same decade. But equally obvious are the political problems. So they’re examining options. One is to tax so-called Cadillac plans only—the most thorough and expensive plans, which tend to be held by higher-income folk. Another is to tax the plans only on those making—you guessed it—$250,000 or more. This doesn’t generate nearly as much revenue, but it solves a political problem in that it would permit Obama to keep his campaign promise not to raise taxes on people earning less than that. “If it’s at $250,000,” says one knowledgeable Democratic insider, “I don’t think it would give Obama particular heartburn.”

Problem: Charlie Rangel, whose Ways and Means Committee will play a key role on the revenue side, says he’s dead set against all this. And besides, wouldn’t the Republicans just feast on it? Here’s where things get really weird. Last week, some top Republicans unveiled their own plan—and it would tax every employer-sponsored plan! They’d offset it (but only partially) with tax credits for the purchase of plans in the free market. We’ll see how that goes down. As I write, Rush hadn’t weighed in yet.

The second issue is the so-called public option, the centerpiece of Obama’s campaign proposal—a public insurance provider to force competition on the private ones. Obama put forward, and liberals want, a full-on Medicare-style public option. My conversations over the past week lead me to conclude that this is very unlikely. Chuck Schumer has sketched out a compromise that I’m guessing will carry the day. It would force the public option to pay for itself with premiums and co-payments and not government revenues or taxes, partly defeating its purpose. Liberals won’t like it: Keep an eye out for Paul Krugman’s verdict on the Schumer plan. Krugman will probably be right on the substance. But he doesn’t have to get votes.

The Senate and House are working on all this right now. The relevant committees will hold hearings over the summer. Look for a bill around Labor Day, they tell me, and a vote sometime in September. Will it be a perfect ten? No. But insuring 30 million people is not a small thing. Neither is finishing (or starting to finish, let’s say) the last, great unfinished task of twentieth-century American liberalism. When Republicans fought the Clintons in ’94, they knew very well that passage of health care would be momentous: a large benefit once granted is never taken away, and it can shift the country’s entire mind-set leftward for a generation or two. Clinton failed at this—and Obama is determined not to fail in the same way.

Email: [email protected]