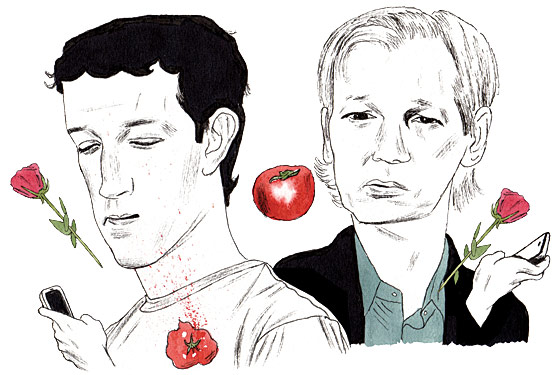

This is a column about a pair of Internet entrepreneurs, the start-ups that they founded, and the tremendous worldwide convulsions they unleashed in 2010. Like many high-tech mavens, the two men in question have many qualities in common. Both are coding gurus of the highest order, brilliant but socially maladroit, elusive and reclusive. Both are at once mono- and (at least somewhat) megalomaniacal. By the time you read this, either one may well have been chosen as Time’s Person of the Year; both are on the magazine’s short list. Yet for all their similarities, there are striking differences, too. The other day, one of them—the 26-year-old American whose company has made him a billionaire—pledged to give the majority of his wealth to charity. Two days earlier, the other—the 39-year-old Australian whose firm has made him an enemy of the state—was thrown in jail.

In case you’ve been on an extended holiday on Pluto, I’m talking here about Mark Zuckerberg and Julian Assange, the creators of Facebook and WikiLeaks, respectively. Even more than their founders, the organizations are alike in important ways: Both are platforms on which great masses of previously private data are made public; they are archetypal institutions of, and catalysts behind, the age of oversharing. As such, Facebook, WikiLeaks, and the guys who fomented them have provoked deeply polarized and at times hysterical reactions. In certain quarters, Zuckerberg is hailed as a social-media hero, and millions of people regard Facebook as an extraordinary tool for connection and community. Assange, likewise, has ardent fans who see him as a liberator of information and WikiLeaks as a shredder of the veil of secrecy that governments use to shroud their serial mendacities. But both have also been subject to fierce and virulent criticism: Zuckerberg and Facebook for sacrificing the privacy of users on the altar of commercial gain; Assange and WikiLeaks for undermining the foundation of diplomacy and putting lives at risk in the process.

These reactions are understandable and, in some cases, warranted. But they are largely beside the point. In a digitized and networked world, Zuckerberg, Assange, and their outfits are merely avatars of the inexorable march toward a radically greater degree of transparency in our personal, cultural, and political spheres. The question about the new transparency isn’t how to thwart it—because we can’t. The question is how we live with it.

Let’s start with Assange. Though WikiLeaks was launched in 2006, it wasn’t until this year that it appeared on the radar screens of most Americans, when Assange uncorked a trio of caches: in July, roughly 77,000 classified Pentagon documents concerning the war in Afghanistan; in October, nearly 400,000 more related to the Iraq War; and, finally, starting in late November, more than a quarter of a million State Department cables (half of which WikiLeaks claims are unclassified).

The backlash to this latest development has been furious, from politicos calling (literally) for Assange’s head to businesses such as Amazon, MasterCard, and PayPal cutting off WikiLeaks’s services and funding (under no small political pressure). The counterbacklash has been equally furious—Internet activists staging retaliatory electronic attacks against those companies, crashing their servers, as well as those of Sarah Palin and the Swedish government, which is trying to extradite Assange for questioning about sexual offenses—and, indeed, has elevated the whole affair to a world-historical event: the first global cyberwar.

There’s certainly plenty of reason to view Assange with substantial wariness. In an essay he wrote in late 2006, he proffered a view of the modern state as an “authoritarian conspiracy” and came off sounding like something very close to an anarchist. His release of the so-called Afghan War Logs exposed the names and locations of civilian informants who were cooperating with NATO forces, effectively a ready-made Taliban hit list.

But Assange has (so far) handled the release of the State Department’s cables in a very different way. Contrary to countless claims by politicians and the media, Wiki–Leaks has not indiscriminately published all 251,287 documents. Far from it: At this writing, the total stands at 1,269. Of those, the vast majority have been vetted, redacted, and published first by one of five respected newspapers: the Times, the Guardian, Le Monde, El País, and Der Spiegel. And yet no one—except Joe Lieberman—is suggesting that the Times may be guilty of a crime, and no one—not even Lieberman—is calling Arthur Sulzberger or Bill Keller a terrorist, as many pols, including Mitch McConnell, have called Assange. Most legal experts believe that the WikiLeaks founder has broken no laws. And nothing like a genuine consensus exists that the disclosure of the cables has caused real harm to American statecraft. “Is this embarrassing? Yes,” said Defense Secretary Robert Gates (no softy, he). “Is it awkward? Yes. Consequences for U.S. foreign policy? I think fairly modest.’’

Despite not having leveled any legal charges against Assange, however, the U.S. and its allies have waged an extraordinary extralegal campaign to shut down WikiLeaks. In light of the ensuing denial-of-service counterattacks, the price of that strategy may prove even higher than it appears now. “They’ve created a group of vigilantes,” says Harvard’s Internet-law eminence, Lawrence Lessig. “Now, with that group having built a cyber-army that’s gone out and flexed its muscles, you have to wonder, once this war is over, what are these vigilantes going to do? What next?”

God knows Mark Zuckerberg wouldn’t likely be able to muster a similar army to rally to his defense—but then again, he’s unlikely ever to need one. Unlike Assange, no grand (or grandiose) ideals, let alone ideological convictions, seem to motivate Facebook’s front man. Even money, contrary to the imputations of Aaron Sorkin’s script for The Social Network, seems fairly meaningless to him; in 2006, when Zuckerberg was 22, he walked away from a $1 billion offer from Yahoo to buy the company.

But in the eyes of Zuckerberg’s critics, what WikiLeaks threatens to do to secrecy, Facebook is doing, or wants to do, to privacy. In its six-year run, the company has changed its privacy policies many times, almost always trying to “help itself—and its advertising and business partners—to more and more of its users’ information, while limiting users’ options to control their own information,” as an analysis by the Electronic Frontier Foundation puts it. Those efforts have often caused a commotion, notably this past spring, when complaints became so loud that government officials in several countries got into the act, and Facebook eventually climbed down. Though Zuckerberg occasionally mouths pro-privacy bromides, his deeper attitude is more relaxed. “We view it as our role in the system to constantly be innovating and be updating what our system is to reflect what the current social norms are,” he has said.

This kind of talk will always give some privacy heads the willies. Yet it’s difficult to argue with its premise or implications: that social norms regarding privacy are, in fact, changing rapidly all over the web and not just on Facebook. In the face of recent calls for a “do not track” registry for the Internet, New York’s reigning venture capitalist, Fred Wilson, opined to the Times: “Tracking technology helps services like Amazon and Netflix make purchase recommendations. Tracking helps newspapers like the New York Times and other online publications place ads that you’ll actually care about … A Web without tracking technology would be so much worse for users and consumers.”

Wilson is right, though there’s no question that people should be given every right to opt out of tracking, just as Facebook’s users should have a simple way to control how much information about themselves is exposed, and to whom. As the web continues its warp-speed metamorphosis, it may be that new laws are needed to strike the appropriate balance between openness and privacy. Just as new laws might be required to deal with the issues posed by WikiLeaks.

What would be a disaster, though, would be for the site to be shut down simply because it has made the U.S. government uncomfortable and grumpy. This is true as a matter of principle, but it is also true for practical reasons. As Lessig points out, there is a strong corollary between the battle over WikiLeaks and the one that once raged over Napster—which, though the record business won in the short term, did nothing to stem music piracy long-term, and indeed created a worse situation for the industry by spawning countless Napster imitators using more advanced and uncontrollable technologies.

Adapting to the new age of radical transparency rather than resisting it won’t be easy for political elites—or the rest of us. In addition to new rules, there will need to be new habits, new systems, and new clarity about what really requires being kept out of public view and the trade-offs entailed in trying to do so. But what Assange and Zuckerberg have taught us is that this new age, predicted since the dawn of the web, is upon us. Pretending we can quash it or wish it away is not just futile, but dangerous.

E-mail: [email protected].