Wednesdays he had come to dread. Wednesdays rolled around, and it was all he could do just to look like someone who gave a damn. Wednesdays meant getting to the stadium at 7:30 in the morning, his knees and neck still uncooperative from last week’s game, only to sit wedged behind a rickety little desk, nodding and note-taking as Coach Coughlin delivered one of his signature militant orations about last Sunday’s matchup, then about this Sunday’s opponent, and then as the offensive and defensive coordinators did their bit: deconstructing various blitz schemes and blocking formations and third-down personnel shifts. This sequence of lectures had once been so enlightening. But by the grim season of 2004 (Giants record: 6-10), it had started to wash over him, a wave of motivational platitudes. “It’s like I’m this 31-year-old kid” is how he describes feeling. “I can’t believe I’m treated like a 12-year-old when I’m 31.” Soon enough, his coaches took notice and started pulling him aside.

“Tiki?”

“Yeah?”

“What’s going on?”

“What do you mean?”

“Are you … bored?”

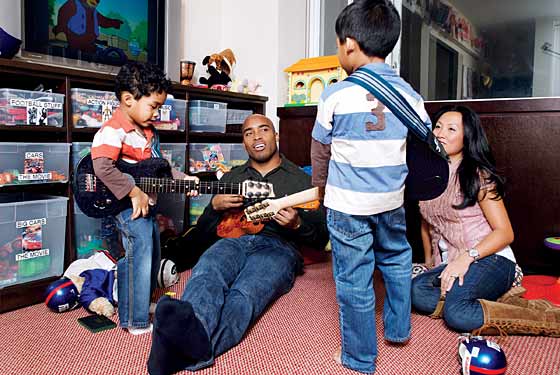

On the Saturday before his last game ever at Giants Stadium, Tiki Barber, the best running back in team history, sits slumped in a plush armchair in the sun-splashed living room of his Upper East Side apartment. Dressed in all black—black jeans, black cashmere sweater, black socks with a hole in one heel—he is a still point in a house of movement. His wife of seven years, Ginny, is fixing lunch in the kitchen; his two sons, A.J. and Chason, are chasing each other around a Christmas tree; and Ginny’s parents, who live with the family, are trying to get the boys into their jackets. Barber, meanwhile, is attempting to explain how he became so disillusioned with football that he decided to make this season his last.

“It’s like when I was in high school,” he says. “I never made below 100 percent on any assignment in math. The teacher would explain it once, and I’d have it.” He pauses to take a bite of the roast-beef sandwich that Ginny just dropped in his lap before running an errand with the kids. “The same thing,” Barber continues, “is happening to me as an NFL player. They explain, I get it, then they keep re-explaining it for another twenty minutes.” He speaks deliberately, projecting the same cool, vaguely mechanical confidence he does on the field. “I’ve gotten really good at it. The problem is—and the reason I know it’s time for me to go—is that I know I’m good at it. I don’t have to pay attention anymore. I’ve lost my … ” He considers, rephrases. “The challenge is not so much there anymore, which has caused my passion to wane.”

It’s a funny thing, the psychology of ambition: how even the most outsize dreams have a way of losing their potency the moment they’re attained. Stranger still is how a decrease in passion often brings about an increase in focus and skill. A graph charting Barber’s incredible rate of mid-career improvement and another showing his growing disenchantment with the game would reveal something curious: The rates of incidence are identical. “It’s true, isn’t it?” Barber acknowledges, flashing the halogen-bright smile he’s hoping will make him the rare athlete to have a broadcasting career that transcends sports reporting. For several months, he has been in negotiations with ABC, Fox, and NBC; it’s something he’s been itching to do since last year, when he was invited to Israel by former prime minister Shimon Peres, a trip that piqued his interest in hard news. “I became fascinated,” he says, “with history and how people think and what motivates people.”

His ambition is not what’s surprising; it’s his timing. “It’s only happened a handful of times that one of the best players decides to walk away,” says Cris Collinsworth, the star receiver who now does commentary for NBC and who has been particularly vocal in his bemusement over Barber’s decision to quit. “For all of us who were forced out due to age or injury, you get an uncomfortable feeling,” he says. “Like, if only I could switch bodies with this guy, I’d still be playing.” Collinsworth also suspects that Barber might be romanticizing the world of television. “Don’t get me wrong, I love my job,” he says. “But all of a sudden you’re just talking about other people. It’s like being a parent: The broadcaster is suddenly the least significant one in the family.” Collinsworth equates Barber’s early retirement with “forgoing childhood”—an odd analogy, perhaps, but one Barber would understand.

After all, pro athletes are in the rarefied company—ballet dancers, artists, and chess prodigies also come to mind—of those whose adult careers are a direct extension of childhood hobbies. They are born with a freakish ability, which is coddled and exploited before they have time to consider the alternatives. It is a narrow coming-of-age: childhood abbreviated, adolescence hyperextended. This evening, Barber will head to the Glenpointe Marriott in Teaneck, New Jersey, where the team sleeps before home games. There are few things he will miss less. “We have a curfew!” he says, shaking his head. “I have two kids, I’m married, and someone’s knocking on my door to make sure I’m here. Are you kidding! I kind of want to grow up.” Another bite of his sandwich, and then this, a realization that only became clear in recent years: “As long as you’re playing a kids’ game, they’re gonna treat you like a kid.”

Barber, then, finds himself arriving late to a universal milestone of growing up: He is making the first major professional decision of his adult life. He considered quitting after the 2004 season, and again after last year, in which his 1,860 rushing yards and 530 receiving was the second best combined total of any running back in league history. But it took time before leaving the game seemed logical. “When you start to get those desires not to do it anymore, you still feel like it’s holding you,” he says. “You feel like you have to do it, or you should.”

“We have a curfew! I have two kids, I’m married, and someone’s knocking on my door to make sure I’m here. Are you kidding?”

For years, he joked about quitting to his twin brother, Ronde, who plays cornerback for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. “The past few seasons, he’ll come to me and say, ‘This is my last year,’” says Ronde. “I started to realize that Tiki was not so much in love with football anymore and that it was only a matter of time.” As close as the two are, Barber didn’t consult his brother about his final decision. “I don’t care what you do as long as you get 10,000 yards,” Ronde told him. After rushing for 1,662 yards this year—fourth overall in the league—Barber finished the regular season with 10,449 for his career.

“Until now,” says Ronde, “we’ve been doing the same thing our entire lives. The moment it came out, people came to me, like, ‘So, are you gonna retire now?’ I still love getting up in the morning and going to practice. Some people play for fun, but I think Tiki played the game so he could master it. Tiki has always been very concerned about not being defined only as a football player.”

To spend time around Barber is to see how relentlessly the game defines his life, like it or not. Aside from a 52-inch flat-screen television, the most dominant feature in his living room is a trophy case that takes up an entire wall: plaques and jerseys and bronzed footballs commemorating a variety of accomplishments, many of which are the sort few players ever receive. He goes to check his e-mail, and there he is, first as a Tiki Barber screensaver and then as Tiki Barber desktop wallpaper. At a recent taping of Fox & Friends, the morning show he until recently co-hosted on Tuesdays, a production assistant popped his head into the makeup room to ask how Barber thinks he’ll play on Sunday. Why? Because the assistant was thinking of trading Barber from his fantasy team. (“Don’t drop me—I’ll score you two touchdowns,” said Barber, who ended up scoring three that week in his best game ever—234 yards—against the Washington Redskins.) His two boys sleep under a massive mural of Giants Stadium, in which they are depicted cheering for their father, and this afternoon, when they return from their errand, they have purchased composition notebooks from CVS featuring a holographic image of their father on the cover. Turn it at the right angle and you watch No. 21 sprint across the field, the ball held high and tight to his chest in the trademark style he adopted to cure his once-notorious fumbling issues.

“Who is that?” Barber asks 2-year-old Chason.

“It’s you!”

“I thought it was you,” Barber teases.

“It’s you, Daddy!”

Star running back, all the time. Even to your children. At moments like this Barber seems fatigued, and it’s easier to see why he uses words like “liberating” to describe a move that will mean less fame and less money. (His current Giants salary is $4.5 million, which he nearly doubles through endorsements he’ll have to give up in his new career as a journalist.) Besides, the game he is retiring from is not the game he started playing. “It is a cold business,” he says. “It’s hard for me on this team. All my friends that I grew up and became a Giant with are gone.” Amani Toomer, the team’s veteran receiver, has been injured since mid-season. Running back Greg Comella, one of Barber’s best friends, left the team five years ago. Kerry Collins, the former starting quarterback, took off when Eli Manning, a first-round pick with a royal surname and $50 million contract, was picked up.

“It’s easy when you’re 22 to not feel jaded by the politics,” says Barber. “You’re so focused on becoming a star. But then you see your friends getting unceremoniously—sometimes ceremoniously—dismissed. You see guys who are a high-round draft pick playing because they’re a high-round draft pick.” For a moment, he seems to think better of being too specific, but then he figures, what the hell, he’s out soon. “Coach Coughlin’s first year we were maybe 5-2,” he says. “Kurt Warner was our starting quarterback. Then he had a couple bad games, and all of a sudden we have a rookie”—Manning—“starting for the rest of the year. We subsequently lose six games in a row. Yeah, it was great for Eli because he gained great experience that benefited him the next season, when we went 11-5, but it’s like, Where did that come from?”

More than the grind of politics, there is the pain, searing and constant. And running backs—relatively small guys who get hit on almost every play—see the worst of it. Barber has carried the football 2,217 times in his decade with the Giants, and most of those runs ended when he was crushed by multiple bodies weighing a hundred pounds more than him. On Mondays a familiar scene plays out in the apartment: The boys want to go to the park, but Barber can’t take them. “It’s all I can do just to sit up and feel normal walking around,” he says, “much less going to a park and chasing two kids around, helping them ride their bikes or play ball. It’s frustrating. I’m beat up and worn out.” He gives an example of a memorably brutal week: “Philadelphia, second week of this season. Jeremiah Trotter”—the Eagles’ unapologetically rabid linebacker—“literally hit me every play. I couldn’t get out of my bed without doing this.” Barber uses his hand to slowly lift his head. “I had a strain in my scapular muscular area. When I was 22, I’d get that injury and feel fine by Wednesday. It was Friday, and I didn’t think I’d be able to play. I got worked on five times that week. Acupuncture, two chiropractic appointments, and ART, which is active release technique, and two massages. Just so I could play!”

The pain is worse, he hears, once you quit. Barry Sanders told him this, as did Frank Gifford. Your body is no longer strong enough to mask the sprains and tears that will haunt you as an adult. Percocet with your morning coffee, a lifetime of knee replacements: Barber hopes to avoid becoming another cautionary tale. “Look at Earl Campbell,” he says of the Houston Oilers star from the late seventies and early eighties. “He can’t even walk. He has a wheelchair or a walking stick. He’s 50! That’s nineteen years for me. I don’t want to be that way.” He knocks on the wooden side table. “It’s a great living, I’ll tell you, but you mortgage something down the line.”

A few days later, Barber wakes up at three in the morning, puts on a blue pin-striped suit, and hails a cab to Fox’s studios for one of his final tapings of Fox & Friends. Sleepy-eyed under the fluorescent lights of his basement cubicle, Barber spends an hour highlighting headlines with reliably alarmist TV value (“JonBenet Slay Haunts Holidays,” “U.S. Out of Love With Marriage”) and tweaking his intros, one about U.S. immigration policy, another about the least painless ways to return holiday gifts. A young assistant preps him on a best/worst gift segment; another offers him a slice of cold pizza. This is the bush leagues of television, but Barber seems at home, curious, even giddy. “Waking up, that part is hard,” he says. “Once I’m here, I love it.” For the moment, he is no longer a football player.

Then the moment passes. A barrel-chested stage tech comes by, trailing his gawky teenage son. The boy is beaming, but too shy to speak.

“Will you sign this for my son?” asks the stage tech, nudging the kid forward with a football.

Barber gives him a smile. “Of course.”