The last time the New York Yankees didn’t make the postseason, there was no postseason. It was 1994, the year a strike canceled the World Series. The Yankees’ closer was Steve Howe, who is now dead, and their two hottest minor-league prospects were Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera. The team has spent the last twelve Octobers freezing deep into the night in front of a tense, Rudy Giuliani–led crowd. But this year looked to be different, even in the context of other recent early-season scares. They fell 14.5 games behind the Red Sox in May. Stars like Mike Mussina, Jason Giambi, and Johnny Damon have suffered some of the worst years of their careers. The pitching staff has included gentlemen named Matt DeSalvo, Jeff Karstens, and Chase Wright. The signing of Roger Clemens was announced with immense fanfare, but the Yankees will end up having paid about $18 million for less than twenty starts of average pitching from a 45-year-old man.

Given all that, at press time, the statistical analysts at the Website Baseball Prospectus list the Yankees as having a 99 percent chance of making the playoffs. And though the Yankees have drawn some life from portly Nebraskan relief wunderkind Joba Chamberlain and resurgent veterans Andy Pettitte and Jorge Posada, the real reason they’re headed to the postseason again is third-baseman Alex Rodriguez—baseball’s best player, a lock for the American League MVP award, a superstar having the best season of a career that would already put him in the Hall of Fame even though he has years left in his prime. Without Rodriguez, the Yankees would be lost; with him, they could win it all.

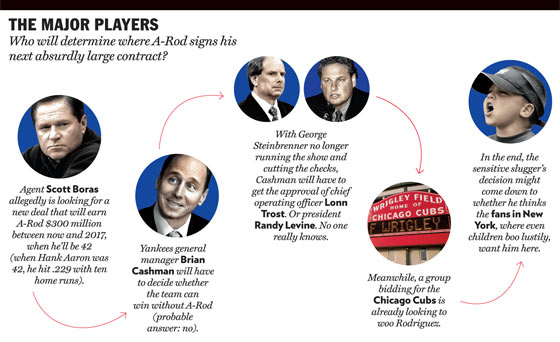

Yet in less than a month and a half, there’s a chance he could opt out of his contract—the biggest in sports history—and voluntarily leave baseball’s wealthiest and most successful team. It depends on how Rodriguez plays in the postseason; it depends on how a cadre of Yankees insiders in the dawn of the post-Steinbrenner era can work with A-Rod’s agent, Scott Boras. If Rodriguez leaves, the repercussions for the future of the Yankees organization could be enormous. And in the end, what happens might depend less on the actions of any one person than it will on the mood at Yankee Stadium the moment the team finishes its last inning of the year.

For the particular timing of this dramatic situation, we can thank Scott Boras. The Über-agent is Rodriguez’s longest-standing comrade in baseball—A-Rod has been represented by Boras since he was drafted at age 17. Boras is arguably the sport’s dominant economic force. His agency, the intimidatingly named Boras Corporation, has been called the “31st franchise”; if its top clients were on a team together, they’d earn $253 million a year total ($55 million more than the Yankees) and easily be the best squad in the game. He’s single-handedly revolutionized the amateur draft with a simple strategy—if his clients’ salary requirements aren’t met, they sit out and reenter the draft the next year. He’s negotiated the largest contract in history for a player entering the league from Japan (the Red Sox’s Daisuke Matsuzaka). And, of course, he’s negotiated the biggest contract in sports history—the $252 million, ten-year deal that Rodriguez received from Texas Rangers owner Tom Hicks in 2000.

In that transaction, A-Rod got everything he could have possibly wanted, but when the Rangers failed to finish above. 500 in three years with him on the team, he also got a reputation as a mercenary whose salary had crippled his team’s ability to pay the other players needed to win games. It’s arguable: Maybe the Rangers could’ve found better teammates for the same price, and maybe they could’ve spent more thanks to the revenue A-Rod brought in. Regardless, the boos started to rain down in Texas, and Boras looked for a way out. The Red Sox were very close to finishing a trade, and Rodriguez had even agreed to lower the overall value of his contract in order to make things work, but the Players Association objected and the deal fell through in December 2003.

The Yankees stepped in two months later, of course, and nabbed him. Hicks agreed to pay close to $10 million per year of A-Rod’s contract. That made Rodriguez relatively cheap for the Yankees. But back in 2000, Boras had thought to include a clause allowing A-Rod, after seven years, to opt out of the contract and become a free agent.

Given Boras’s style—which has been called “ruthless,” but in the incompetence-plagued world of pro-baseball management might be better described as “not boneheaded”—and simple common sense, the possibility seems small that Rodriguez, after the best year of his career, won’t sell high. And there are plenty of teams out there ready to bid for his services. The leading competitors are the Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs. Other, less likely possibilities include both Los Angeles franchises, the Detroit Tigers, and, if they can figure out a place to play him, the Mets.

The team that observers believe has the best shot is the Cubs. They’re up for sale, but a source with knowledge of the situation says Boras knows which group is most likely to be awarded the team. (That’s not loudmouth Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, by the way; he has no chance.) The source says Boras has already been in touch with that group about the possibility of a contract that could reach $30 million a year over the next ten years while deferring a certain portion of money toward an eventual stake in the franchise. It would be another historically huge deal. Rodriguez would be 42 years old at the end of it; Cal Ripken Jr., the Iron Man, retired at 41.

Regardless—if that’s what the Cubs want to pay, the Yankees will have to match it. But it goes beyond simply deciding they’re going to outbid the Cubs and Red Sox; they have to do it before those other teams bid. The minute that Rodriguez becomes a free agent, the last three years of his contract are void—and the $29 million the Rangers are chipping in over the next three years are gone as well. If the Yankees can extend A-Rod’s deal before the deadline, they can keep the $29 million. If not, it’s gone, and it’s extremely unlikely they will let that money evaporate and then remain in the bidding.

The first day Rodriguez can opt out of the contract is ten days after the World Series ends. The latest the Series should end is November 1. That’s a big decision for the team to make quickly. But who’s going to make it?

It seems odd to have gotten 1,100 words into a story about the Yankees without a single appearance from George Steinbrenner, but thus it goes these days. Steinbrenner was recently described by Portfolio magazine as having little idea what’s going on around him, and his succession plan has been blown up by the pending divorce of Steve Swindal, toppled chairman of Yankee Global Enterprises, and Steinbrenner’s daughter Jennifer. The split has fueled speculation over who will inherit the team, but that’s an issue for a later day with Rodriguez and Boras capable of testing the market this off-season. G.M. Brian Cashman is in charge of baseball operations, and without Steinbrenner to interfere, he’s shown a level of clearheadedness that gives no reason to indicate he’d want to lose the best player in baseball. Cashman doesn’t cut the checks, though it’s not like the money isn’t there, in the form of the YES Network. SNL Kagan has estimated that YES made $136 million in profit last year. The financial decision, insiders say, could be heavily influenced by Lonn Trost, the Yankees’ C.O.O., the guy who knows the true ins and outs of the Yankees’ business. YES, for example, was his brainstorm. In the middle of it all is Randy Levine, the Yankees’ president, who’s known to have difficult relationships with Cashman and manager Joe Torre. Levine has driven the construction of the team’s new stadium; he believes A-Rod is financially indispensable to the franchise, especially given the investment in the new park, and is pushing to re-sign him at almost any cost.

Who has final say? Who knows? With no formal hierarchy in place, it will come down to a Hobbesian knife fight. It could be reminiscent of the power struggle that took place between Red Sox G.M. Theo Epstein and team president Larry Lucchino after the Sox’s 2005 playoff flameout, which ended with Epstein quitting and leaving Fenway Park in a gorilla costume (he returned months later, his position considerably stronger). And that happened with a hands-on owner in firm control of the franchise.

What does the man in the middle think about all this? In most sports-contract negotiations, a player’s input is either negligible (they’ll go where the money is) or predictable (they want to live near home or play on a winning team). But with A-Rod, existing eccentricity (when he was with Texas, a Sports Illustrated profile reported that on a visit to Boston, he’d walked around Harvard Square initiating conversations with students) has combined with massive scrutiny and some ill-timed groundouts to produce a quite unusual situation.

To wit: Since early September, Rodriguez has developed what might charitably be called a “tic.” When he reaches base, he rotates his left shoulder while holding his right hand over his heart. He claims that he’s stretching out a jammed shoulder. It’s an odd maneuver; it makes him look like he’s in pain. As Rodriguez rounded the bases after hitting his 50th home run in early September, becoming the first Yankee to hit that many since Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, the Yankees bullpen, almost in unison, began rotating their left shoulders and holding their right hands over their hearts. When A-Rod reached the dugout, several other teammates were doing the same thing. As the blog Bronx Banter pointed out, an MVP, carrying his team to the playoffs, facing impending free agency, was being mocked for his idiosyncrasies the second he was cementing himself as the team’s best slugger of the past 50 years. However good-natured it was, it’s the kind of thing that does not speak to an undying attachment between player and team.

On the field, the major knock on Rodriguez has been that he didn’t “come through in the clutch.” Statistical analysts might debate whether such an animal as “clutch hitting” exists, but Yankees fans have no doubt. The notion that some players like Derek Jeter have a champion’s biochemistry is particularly strongly held in New York. Rodriguez was booed relentlessly last year for alleged clutch dysfunction. In last season’s four-game ALDS loss to the eventual American League champion Tigers, he went 1 for 14 with four strikeouts, prompting Torre to bat him eighth in the deciding fourth game. His most famous postseason moment, to date, is his illegal attempt to slap the ball out of Red Sox pitcher Bronson Arroyo’s glove in the 2004 ALCS. As every Yankees fan knows, the team has failed to win a World Series since acquiring Rodriguez. This year, though, he’s led the league in RBIs and hit several dramatic home runs late in games. He hasn’t been booed much lately.

He has not, however, gotten off the hook with the New York media. When Rodriguez and Boras sit down this off-season and make their pros-and-cons chart, you’d have to imagine “Chicago Tribune Won’t Run Photo of My Night Out With a Buxom Blonde and Write That I’m Into the ‘She-Male, Muscular Type’” would be rather high up the list. When A-Rod was in Seattle and Texas, this was something he never had to worry about; if he actually did cheat on his wife on the road, this would make him like nearly every other athlete in sports and would not be reported upon. He’s been stoic about it, but perhaps that just proves a point. He has a history of being sensitive when he’s felt unwanted—and he certainly hasn’t been hanging around NYU making conversation with undergraduates lately. In 2003, remember, he was willing to take a cut in his record-size contract to facilitate a trade to Boston. On a certain level, Rodriguez, no matter how high the money figures go, has to wonder if the juice is worth the squeeze in the Bronx.

If A-Rod plays well and the Yankees win the World Series, it’s a moot point. Everyone’s happy; management offers a massive contract—they’ve got enough money to outbid anyone, in the end—and he accepts. But what if he struggles and they lose? What if he struggles and they win? Maybe he’s earned enough goodwill this year that the tide has turned. But maybe the crowd will boo and the sports pages will vituperate. Even in that scenario, the Yankees will likely still bid as much as anyone else: Cashman knows that the team would never have even made the playoffs without him; Trost, unlike Steinbrenner, is a moneyman who will rely on Cashman rather than emotion; even Levine, Steinbrenner’s heir in unpredictability, is set on bringing A-Rod back. But if the fans don’t want him, A-Rod’s history indicates he won’t want to be here. Boras’s history indicates he can certainly find a satisfactorily gigantic pile of money elsewhere in America. And losing A-Rod—with the consequent near-guaranteed crumminess of next year’s team that entails—is the kind of catastrophe that could leave the tenuous Torre-Cashman-Trost-Levine management system in ruins, ending the Yankees as we’ve known them for the last twelve Octobers. In the end, the Zeitgeist may have the final say. So take heed, Yankees fan. The future is in your hands.