These days, we New Yorkers are all gripped by a collective fear that the good times have come and gone, and who can say when they’ll be back? Right now, it feels like never. But the New York Yankees do not operate this way. The interlocking NY stands, perhaps alone, as the last symbol of New York’s self-evident, world-sanctioned superiority. The Yankees expect to be the best, period. It’s tough to find anything else left in New York that holds that kind of power. You can sell that. You can sell that anywhere.

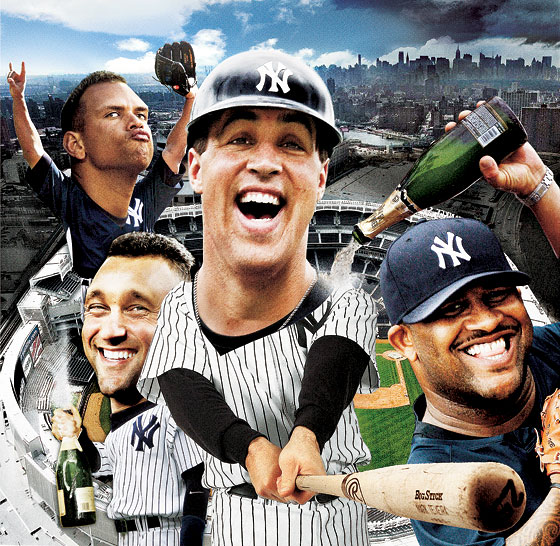

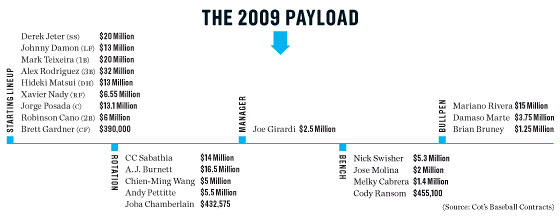

So while the rest of us are tightening our belts and bracing for the worst, the Yankees are opening a state-of-the-art, $1.6 billion stadium. While the executives at AIG are held out as venal masters of destruction and shamed into giving up their bonuses, the Yankees are spending $423.5 million on three players. While the housing market tanks and nobody will buy so much as a pair of socks unless they’re 75 percent off, the Yankees dished out two and a half times more money this off-season than the rest of the American League combined.

It’s not that the Yankees didn’t take their licks, just like the rest of us have. Last year, the Yankees missed the playoffs for the first time since 1994, when there were no playoffs. But their response was not to cower, or to reevaluate their methods, or to try to play by the same rules as the rest of the world. They did not renounce their ways: They went all-in. Downturn in the economy? Hey, screw that. That’s loser talk. You see those three top free agents they have there? We’ll take all of them, thank you. The Washington Nationals built a brand-new stadium and watched attendance fall to half-capacity by the second game? Pshaw, like we’re the freaking Nationals. The rest of baseball cutting ticket prices and slashing the payroll? More for us, please!

Oh, and if all that weren’t enough: The Yankees, as always, dominated headlines off the field as well, starting with the since-forgotten DUI arrest of phenom Joba Chamberlain, segueing into former manager Joe Torre’s “tell-all” book of his time in the Bronx, and culminating in the grandest spectacle of all, the ongoing psychodrama that is Alex Rodriguez, busted with madams, busted with steroids, busted with injuries, busted, busted, busted. A-Rod has become the city’s Octomom, a bubblegum gossip distraction from the all-encompassing misery. The Yankees are in the entertainment business, and whatever else you might say about them, they never, ever, fail at that.

In Yankee Land, it is always 1927, and 1961, and 1998. It is not enough merely to win: The Yankees must dominate. Even without a World Series championship since 2000—2000! It really has been that long!—that is the brand. If the Yankees aren’t world conquerors, lording their financial and cultural superiority over the penny-pinching peons that make up the rest of baseball, then who are they?

Okay, so the Yankees are not entirely immune to the economic crisis—Bank of America just last month dropped out of a rumored $20 million annual “signage” deal at the new stadium, and the team hasn’t quite sold out their pricey luxury boxes—but you’d have a hard time convincing Mark Teixeira of that. The absurdly muscular first-baseman agreed to an eight-year, $180 million contract right before Christmas, outbidding the Angels and the Red Sox, and one could make the argument that he’s the Scott Boras client that Boras would love Alex Rodriguez to be. He’s polite to a fault, robotic when answering questions, and does nothing but talk about how much he wants to win, take it one game at a time, give 110 percent, and so on, ad nauseam.

“The reason I signed with the Yankees is because it’s not about one player. I knew I wouldn’t be the center point of everything going on,” Teixeira says. “Anytime you have the biggest contract on the team, it does add more difficulty to your job. Here I can be just one of the guys.”

This is absolutely true, and at the center of what makes the Yankees different from every other professional sports franchise on earth. Teixeira is the highest-paid first-baseman in baseball history and the third-highest-paid player today (behind A-Rod and Derek Jeter), and, somehow, he is an afterthought this off-season. Greta Garbo loved New York City because, among the millions of people, it was the one place she could be left alone. In almost any other city, Mark Teixeira would be on the front of every program and piece of memorabilia. Here, on the most famous sports team in the world, with everyone watching, is the only place he can be left alone. (It also doesn’t hurt that he’ll be living in Greenwich, Connecticut.)

Teixeira might be the highest-paid first-baseman in baseball, but he’s not the best. (That would be St. Louis’s Albert Pujols, who won’t be a free agent for at least two more seasons.) He’s still a relatively safe bet for eight seasons because he’s a switch-hitter, he’s consistent, he’s rarely injured, and he’s playing a position that allows you to age gracefully. But he’s a notoriously slow starter—something he’s fully aware of: “It’s not something I’d like following me around the rest of my career,” he says, grimacing as much as a robot can grimace—on a team that, without A-Rod in the lineup for at least a month, will need him to hit early and often. But don’t expect him to become any sort of fan folk hero: Boras has not wired a “charm” function into his hardware.

CC Sabathia, on the other hand, is in the grand tradition of lovable baseball lugs like John Kruk, Rich Garces, Babe Ruth, and David Wells: He’s fat. (After he was traded to the Brewers last season, joining equally rotund first-baseman Prince Fielder, The Onion memorably uncorked a “CC Sabathia, Prince Fielder Keep Imagining Each Other As Giant Talking Hot Dog, Hamburger” headline.) Sabathia is gregarious, emotional, and community-conscious (he has implored Major League Baseball to improve its inner-city youth programs in the wake of dwindling numbers of African-American players in the bigs). He’s also nearly as rich as Teixeira: Sabathia signed a seven-year, $161 million deal, making him the highest-paid starting pitcher in baseball (currently, for the record, the Yankees have the highest-paid starting pitcher, closer, first-baseman, shortstop, third-baseman, and catcher in baseball). After his dominant run with the Brewers last year, there was considerable wangling for other deals and an unconvincing “I don’t want anybody to think that I didn’t want to come here” statement from the native Californian at his press conference. Many have questioned the deal, not because of Sabathia’s body of work but because of his body of, well, body. Sabathia really is huge. He is listed at 290 pounds, but that is being exceedingly kind. After every start, pitchers wrap their throwing arm in ice, gauze, and padding to soothe the violence they put it through. On most pitchers, it looks like a huge elephant tusk. On Sabathia, it looks like dandruff.

Sabathia seems to have overcome any inner turmoil he might have had about coming to New York. “We’ve got a chance to be a real special group,” he says. “I mean, look at everybody here. That’s Mariano Rivera over there. Come on, man.” And yes, he finds the pinstripes slimming. For now, anyway: It’s unlikely Sabathia’s going to lose weight over the next seven seasons—in case he ends up not liking it here, he has an opt-out clause after three years—and pitchers with his girth tend not to have long, healthy careers. Particularly those who have thrown 513 innings over the last two years, by far the most in baseball, many of them under the extreme stress of pennant chases and the postseason. All pitchers are fragile, and if Sabathia suddenly blows a gasket or tears a tendon—and we’ve certainly seen it before, from Jaret Wright to Carl Pavano—the Yankees are on the hook for a lot of empty money for a very long time.

He’s still not the biggest injury worry of the new additions, though: That’s A. J. Burnett, who, when healthy, might have even more overpowering stuff than Sabathia. The problem is that he’s only been upright enough to show it three times, perhaps not coincidentally in seasons right before he was due for a pay upgrade. He won’t be due for another one until 2013 now that the Yankees have wrapped him up for five years. He has looked outstanding this spring and pitches with an effortlessness that’s beguiling, and misleading. “I’ve grown up a lot since I was young,” he says. “I’m not trying to throw the ball through a wall anymore.” Well, we’ll see.

A lower-profile addition this year, but one who seems determined to make himself into a fan favorite if it kills him, is first-baseman–outfielder–utility man Nick Swisher, a former hot prospect in the A’s system who hit 35 homers three years ago but stumbled to a .219 average with the White Sox last year. Swisher, unlike the other additions, didn’t choose to come here: The Yankees got him on the cheap in November, giving up one Wilson Betemit. Swisher is, to put it mildly, a dervish of noise and look-at-me-I’m-wacky energy. (Sample quote: “As soon as you wake up, it’s a great day, because, hey, I woke up!”) He has a Twitter page, which he uses to tell the world things like “Went out to dinner with some of the guys. We’re doing lots of running … more than I ever have done before. So great!” and is doing what he can to become Sabathia’s little buddy Gilligan. (He says he signed up to Twitter “because CC did” and used one of his first few tweets to say how much he was looking forward to Sabathia’s arrival in Tampa.) Swisher, suffice it to say, is a ham (and, as the glass of water I was drinking in the Yankees locker room while talking to him can attest, careless with his freshly clipped toenails). Most of the time, reporters follow players around to try to get them to talk to them. With Swisher, the opposite is happening: He’s chasing reporters. He clearly hasn’t been here very long.

“When I got traded over here, I was thinking, ‘Man, I gotta calm it down a little bit.’ This is the New York Yankees!” he says. “But then I realized, ‘Hey, it’s stuffy in here!’ So I cranked up the Bose speaker and turned it into Dance Party ’99 over here.” Swisher laughed, began to do a little dance, if it could possibly be called a “dance,” and cackled some more before heading over to talk to Sabathia.

A few lockers over, Mariano Rivera watched him prance by and did not change his expression. The new guys are a small part of this brand. Bose speakers and Twitter pages aside, they’ll blend in soon enough. The true Yankees have been here for a while. Some have won titles. Some haven’t. But they’re all getting older and are burdened with dramas of their own. The way we look at them, the way we remember them: That might not be the way they are anymore.

Tampa’s George M. Steinbrenner Field, the spring-training home of the Yankees, exists to satiate the fan’s nostalgia. The famous façade spans the grandstand, and the field has the exact dimensions of the old and new Yankee Stadiums. Outside, there’s a mock Monument Park featuring the retired numbers of all the Yankees greats. The scoreboard even plays the same videos on the Jumbotron, which can be strange, considering you’re watching the famed subway race in a city that lacks adequate public transit. Steinbrenner Field—built in 1996, it was renamed from Legends Field for the Yankees owner before last season—is to the old Yankee Stadium what Las Vegas’ New York–New York casino is to New York City: smaller, faker, sunnier, more comfortable, and palatable for retirees, lazy tourists, and those too averse to perceived urban squalor to actually visit the real thing. (And parking’s easier to find, too.) Outside one spring-training game, a man, with his son clad in a JETER 2 jersey and carrying a sack of baseballs for players to sign, asks an usher if he’s ever been to New York City. “I’ve never been,” he says. “Is the subway really that dangerous?”

Retired Yankees are all over Steinbrenner Field during spring training. Following the unwritten rules of old-timer etiquette, they all put the uniform back on, like little kids in pajamas, and mingle with fans and current Yankees, dipping into that Yankee mystique and all it still holds. Goose Gossage watches the pitchers run sprints on a practice field, his mustache as gigantic as ever. Tino Martinez looms around, devouring the free clubhouse food. Yogi Berra, 83 years old now, shuffles through the locker room, feeble but still iconic, a living piece of American folklore.

C C Sabathia is in the grand tradition of lovable baseball lugs like John Kruk, Rich Garces, Babe Ruth, and David Wells: He’s fat.

And then there is Reggie Jackson, still the straw that stirs everyone’s drink. When Reggie is in the room, no one else is. The players revere him—“That’s Reggie fuckin’ Jackson!” gasps Swisher—the fans surround him (when he happens to slip into the sight of the general public), and beat reporters, still, stop whatever they’re doing to sidle up to him. Reggie’s the mayor of Tampa, the main link to the “Bronx is burning,” Billy Martin, Steinbrenner-in-his-prime days. With Mickey Mantle gone, Reggie is the closest thing to the embodiment of Yankees as breathtaking drama, living a big life on and off the field and, most important, winning championships.

Reggie knows everybody, the clubhouse attendants, elevator operators, weight trainers, and security guys. Before one spring-training game in mid-March, a couple of reporters waited outside the Yankees clubhouse for entry, talking up a security guard with a Gossage-inspired Fu Manchu. In walked Reggie, who called out the guard’s name and slapped him on the back. The guard was holding a copy of that day’s Post. On its cover: The Details photo of Alex Rodriguez, in which he appears to be kissing a mirrored reflection of himself. Eager for a connection with Reggie, the guard showed him the paper. “You see this shit, Reg?”

Reggie picked up the paper, and his face went ashen. “Naw … aw, hell no,” he said, jaw dropped, stunned, as if the picture were of A-Rod having relations with a barnyard animal. “Naw. That ain’t what he’s doing. That ain’t … aw, man, that’s just not right.” He thrust the paper back toward the security guard as if it were on fire and then scurried into the locker room, slamming the door behind him.

When you talk about the Yankees and what they really are, rather than what they’d like to stand for, you have to start with A-Rod. As much as we might like Derek Jeter to be the face of the Yankees today, he isn’t. Not anymore. When you demand the best and the brightest for your franchise, money and psyche be damned, sometimes you end up with Alex Rodriguez. It’s been quite the dirge for A-Rod this winter. We had Torre claiming in his book that the rest of the team referred to him as “A-Fraud.” (Whether this was meant as an insult or amiable teasing depended on whom you talked to.) We had A-Rod gallivanting around with Madonna, a woman seventeen years his senior but several light-years ahead of him in the field of managing public relations.

And mostly, we had the steroids, which hurt A-Rod not so much in that he took them—after all, no one seems angry at Andy Pettitte and his HGH anymore— but more because it confirmed A-Rod as a soulless phony. A-Rod and the Yankees dominated nearly every tabloid cover for more than a month, and not even Rodriguez’s discovery of a torn labrum in his hip and retreat to Colorado for treatment bought him much peace. Last week, the Daily News reported that he dated Kristin Davis, madam of the same prostitution agency that serviced our former governor.

A-Rod’s injury rehab has gone better than expected, and, if everything falls perfectly, he could be back with the team by May 1. (Which is nice, considering the Yankees are paying him $32 million this year.) But A-Rod’s preseason surgery was a bit of a split-the-baby procedure—he’ll need to have another surgery once the season ends—and there’s little precedent; no one knows how much he’ll resemble the slugging A-Rod of old. (You know, the slugger everyone hated.) His temporary replacement, Cody Ransom, is unlikely to Lou Gehrig him. Ransom has seven lifetime home runs in six scattered seasons and might be the only Yankee less comfortable around the media than Rodriguez. (When asked what he’d like New Yorkers to know about him, Ransom said, “I love my family.” Anything else? “I love baseball.” Got it.) But Rodriguez will be 34 in July and, as convincingly argued by Über–stat genius Nate Silver in Baseball Prospectus, is clearly on the downward slope of his career. (Silver projects that A-Rod will hit a pitiful four home runs in 2017, a season in which the Yankees will pay him $20 million—a calculation he made before A-Rod’s injury.) Fans aren’t the only ones whispering that, perhaps, the Yankees should have dropped Rodriguez when they had the chance two years ago, when Boras overestimated the market and left the Yankees as the lone bidder for A-Rod. Now they’re stuck with him for a long, long time. As are the rest of us.

What’s funny is that, for all the talk about how much Rodriguez and Derek Jeter supposedly don’t get along, A-Rod has done nothing but make Jeter’s life easier since he arrived here. Everything that A-Rod can’t do, Jeter excels at, whether it’s being smooth with the media, having the look of a Wheaties-box champion, avoiding awful public-relations decisions like the Details photos, keeping his name out of the gossip pages, and, mostly, playing the part of Real Yankee—steroid-free, all-American, the “face of baseball.” Derek Jeter’s popularity couldn’t possibly be higher than it is right now, and much of that is owed to A-Rod.

That works out great for Jeter because—and I’m sorry to sound sacrilegious here—Jeter is just barely an average baseball player anymore. He’s hitting for less power, he’s stealing fewer bases, and his on-base percentage is plummeting; niggling injuries are starting to catch up with him at the plate. And that’s not even getting into his defense, which has been dramatically overrated for years—even Torre, in his book, admitted that his beloved Jeter lacks range at shortstop—and is becoming borderline embarrassing as he hits his mid-thirties. (He’ll be 35 in June.) No matter how many times we watch replays of Jeter’s patented jump throw from the hole at short, every fielding metric available reveals that he has little to no range and a rapidly weakening arm. These are facts that have been obvious to everyone but Yankees fans (and, if you watched Jeter play ahead of Jimmy Rollins at short in the World Baseball Classic, USA manager Davey Johnson) for years now, but we’ve all been distracted by his heroic glow. This season, even the most ardent Jeter booster won’t start to see him as a liability in the field.

What happens then? Jeter’s under contract for this season and next—which should put him just short of 3,000 hits—and it’s difficult to imagine him as the Yankees shortstop beyond that; even Cal Ripken Jr. and Robin Yount ultimately switched positions. Are we ready to look for a Jeter replacement? What will be left of the Yankees Dynasty then? And it’s not just him: Mariano Rivera will be 40 in November, and Jorge Posada 38 in August. Both seem to have recovered from lingering injuries—Mariano has looked particularly overwhelming—but age is age. You better learn to love the new guys. Because the old guys are running out of time.

f the thousands of George Steinbrenner stories, my favorite is still the one about the 1981 World Series, when he called reporters to his hotel room, claiming that he’d broken his hand in a fight with Dodgers fans in an elevator. The story was almost certainly false—no one could find anyone who could corroborate it—and seemed based in George’s deluded notion that his team would play harder against the Dodgers out of a sense of personal injustice done to their leader. (They lost anyway.) Whatever your personal views of Steinbrenner, you have to admit the Yankees are less interesting without him. And since he ceded control of the team to his sons, it has been difficult to figure out exactly who’s steering this ship.

Big George (“Mr. Steinbrenner,” as every Yankee employee refers to him, without fail) has made only sporadic appearances at his eponymous field in Tampa this spring—he sits in his private box and occasionally waves—and his sons Hank and Hal have been conspicuously quiet this off-season. (Hank, reportedly the driving force behind offering A-Rod the ten-year, $275 million contract in December 2007, said only that he was “not personally angry” at the third-baseman and that the team would not try to void his contract.) Chief operating officer Lonn Trost, the brains behind the cash cow that is the YES Network and the overseer of the construction of the new stadium, is loath to dip into personnel decisions. So it’d have to be general manager Brian Cashman, right? Well, one could argue he had his chance.

Before last season, Cashman—who gets along so well with the beat-reporter media hordes that he might as well be one of them; he certainly looks like a beat reporter—made a big show of the Yankees’ youth movement, eschewing big free-agent payouts (other than A-Rod, of course) to trust homegrown talent like Melky Cabrera, Robinson Cano, Phil Hughes, and Ian Kennedy to lay the foundation of a new dynasty. This plan worked terribly: Cabrera and Cano backslid, and Hughes and Kennedy bombed. Once the Yankees missed the postseason, out came the old checkbook, and in came Teixeira, Sabathia, and Burnett. (The two pitchers of the future, Hughes and Kennedy? They’ve both been optioned to Triple A; after Kennedy was sent to the minors, his locker was taken over by Kei Igawa’s translator.) Was this all Cashman’s decision? Is this the way he would like to have done it? Certainly not: Cashman, like his buddy Theo Epstein in Boston, fancied himself a sort of Billy Beane–Moneyball general manager, except with actual money. After last year invalidated his start-the-kids approach, the imperative was clear: Back to basics, spend the cash. Cashman probably would rather not do it this way, but he has worked for the Yankees his entire life and still has a great gig: general manager of the richest, most powerful team in sports, and he doesn’t even have to sit through George yelling at him anymore. So why not stick around? Cashman, it appears now, is just along for the ride, and more or less content about it.

Reporters usually have to chase players to get them to talk. With Nick Swisher, the opposite is happening: He’s chasing reporters.

Same goes for manager Joe Girardi. A longtime catcher in the major leagues and a manager for one tumultuous season with the Florida Marlins, the 44-year-old Midwesterner took over for Torre after a season in the YES broadcasting booth. He is modest, authoritative, well spoken (he has a degree in industrial engineering from Northwestern), and is a True Baseball Man. He takes considerable pride in focusing only on the diamond and avoiding all that swirls around it. This is an intelligent move, though it also sometimes makes it seem like he’s out of the loop. He met Teixeira, Burnett, and Sabathia for the first time at the press conferences introducing them as Yankees, and he communicates with Rodriguez almost exclusively by text message. (“A-Rod texted me that he had the surgery,” he told reporters after a recent spring-training game. “That’s all I can tell you, because that’s all I know.”) A-Rod’s rehab, Rivera’s recovery from off-season surgery, which players will be going to which spring-training games—a lot of that lies outside of Girardi’s jurisdiction. He makes out the lineup, gives players occasional pep talks, answers reporters’ questions after the game … and waits for further instruction. It’s not that he’s uninvolved or incompetent; far from it, in fact. It’s just that with the Yankees, being the manager doesn’t make you the boss.

“For me, it’s a lot of baseball, and a lot of family, and that’s all I worry myself with,” he says. “The face of the Yankees is the players, and Mr. Steinbrenner. Very seldom in this market is the manager the face, because of all the players that are here. I’m asked to manage the team, and that’s what they allow me to do.”

Girardi will take the fall if the Yankees don’t make the playoffs this year, though no one quite knows who will be wielding the ax.

The first game ever at the old Yankee Stadium was April 18, 1923, against the Boston Red Sox. Official attendance was 74,200, Babe Ruth hit a three-run homer, and John Philip Sousa played the national anthem at center field. It’s a shame Steinbrenner hadn’t been born yet. He would have loved that.

There’s no real John Philip Sousa equivalent today, and it’s just as well, because it’d be tough to top that opener. Instead, on April 16, the Yankees will open their new playpen to pomp and circumstance in front of a sold-out crowd on a weekday-afternoon game against the Cleveland Indians. So far, the Yankees have been quiet on details, but you can expect all the greats, from Berra to Reggie, all dressed up in their uniforms, of course. The nostalgia will take them far, considering the Yankees haven’t won a World Series in nearly a decade and are moving into a stadium that has 1,100 flat-panel, high-definition video monitors and whose luxury boxes have “touch-screen Internet-protocol phones” to order hot dogs. The Yankees’ individual-game tickets went on sale last week, and sales were brisk. Season-ticket renewals, despite a massive price hike for the best seats, have been steady, and recently, State Assemblyman Brian Kavanagh proposed legislation that calls for teams that take taxpayer funding to be required to offer “7 percent of all tickets at affordable prices,” which is not something you have to do if a team is having trouble selling tickets.

And, because these are the Yankees, no one seems to mind that various members of Congress have been on the team’s case about all the public financing they received for the stadium, including tax-free public bonds and a new Metro-North station paid for entirely by the city and the MTA. (Heaven forbid Joe Girardi get a bonus, though!) The new stadium will open to endless plaudits, and the team will keep minting money and subsidizing the rest of baseball’s underclass. The Yankees have a monumental new home, and, in contrast to the fervor over the Citi Field naming in Flushing, have continued to walk between the raindrops publicity-wise for it. The Yankees have the best new stadium in baseball. Of course they do!

And through all this spending, all this living off a New York that might have vanished into the financial black hole, it’s worth noting that this team will probably kick ass. The starting rotation of Sabathia, Burnett, Pettitte, Chien-Ming Wang, and Joba Chamberlain has been outstanding all spring, and the offense, with the addition of Teixeira and the return of Jorge Posada, should be strong enough to hold down the fort until A-Rod returns. To put it another way, as of press time, the Yankees still had not decided on a regular center-fielder. It’ll either be Brett Gardner, a slap-hitting 25-year-old rookie who probably wouldn’t crack the Kansas City Royals’ starting lineup, or Cabrera, a middling former prospect who appears to have worn out his welcome with the fan base. Baseball-wise, this is the most pressing issue facing the team—it certainly has many fans frustrated, as if it were inconceivable that they should not have another proven starter to install in center; this is the Yankees!—and if neither works out, the Yankees can just wait for other teams to fall out of contention and trade for whoever bobs up. (The Cardinals’ Rick Ankiel and the Brewers’ Mike Cameron are the most likely candidates.) If this is your worst problem, you’re doing pretty well.

Some of the blame for last year’s “failure” was put on the shoulders of Posada, or, more specifically, Posada’s torn right shoulder. He didn’t play the last two months of the year and had the worst hitting season of his career. He’s looking healthy this spring, gunning down three of four base-stealers in a game last week against Pittsburgh Pirates prospects. Asked if he realized how important he was to the team’s chances in 2009, replied, “I don’t know if I could have made a difference last year. We had a really, really bad year. I could have made it worse.” Last year, the Yankees won 89 games, the seventh-highest number in baseball and more than they won in 2000, the year of their last World Series title. Around here, that’s a “really, really bad year.”

And why wouldn’t it be? The Yankees are a relic of a time when New York did dominate, when we had the best of everything and were the center of the world, of finance, of media, of culture. And the relic persists, the myth goes on. If we cannot sell our financial institutions as the world’s greatest any longer, dammit, we sure can sell our baseball team that way. The Yankees represent all of us, what we once were … and what we might be again.

The Returning Stars

Mariano Rivera

Legendary closer had off-season shoulder surgery. But he’s as dominant as ever, and that cut fastball seems eternal.

Alex Rodriguez

Out until May. Who knows what his mental and physical state will be? But he’s here for the next nine years, so get used to him.

Derek Jeter

Mr. November is coming off his worst season, and he clearly can’t play short anymore. But you be the one to tell him.

Brand-New Toys

A.J. Burnett

Fragile, potentially overpowering starter has a tendency to have his best years when he’s about to enter free agency.

CC Sabathia

The rotund lefty was the best pitcher in baseball last season … but threw a ton of innings. Will he hold up?

Mark Teixeira

Switch-hitting, powerful first-baseman doesn’t dazzle with charm, but he’s already unpopular with Sox fans, which always helps.