He loves it up here, floating high above the crowd and staring down in awe at the scene below. It is Friday night, and Andrew W.K. is perched inside the lighting booth at Santos Party House, the Lafayette Street club he opened with a few friends last spring, which is where he tends to spend most of his time on nights when he’s not hosting the party or performing the pop-metal anthems that made him a presence on MTV a few years back. Thanks to some fluke of the bi-level venue’s acoustics, the 150,000 watts exploding the sound system are funneled into this cramped little nook in just the way Andrew believes music should be experienced: every beat a jackhammer to all sense and reason. But the main draw to the lighting booth, for him, is the panoramic view of the action on the main floor—the sweat-soaked faces glowing under the twirling heart-shaped disco ball, the crush of bodies inside the D.J. booth, the grinding, swaying, and ceaseless hip-shaking—that never fails to instill in Andrew a sense of both pleasure and purpose.

“It’s just kind of absurd,” he shouts over a medley of techno-infused James Brown B-sides, “to think someone can be responsible for creating that, you know?” He takes a sip of whiskey from a plastic cup. He shakes his head. A tall, pale-faced 29-year-old with big, wandering brown eyes and jet-black hair grown the optimum length for head-banging onstage, Andrew has in a sense been preparing to open a club like Santos since long before he knew he’d formally enter the nightlife business. His major-label debut, 2001’s I Get Wet, was a brash, juvenile collection of songs centered around a single theme—“Party Til You Puke,” “It’s Time to Party,” “Fun Night,” and his most famous single, “Party Hard.” Performing in a filthy white T-shirt and filthy white jeans, he crafted a public persona that relentlessly embodied his music, screaming about the soul-edifying powers of fun with an infectious earnestness. This fusion of hair-metal rebellion and hippie love-spreading helped Andrew sell some 400,000 albums and win a dedicated fan base comprising those who truly thought he was rock’s savior (mainly adolescent boys in midwestern states) and others who saw him as an awesome postmodern prank (twentysomethings on the coasts). “It sounds funny, but personally I don’t really like to party,” Andrew says. “What I like to do is create the party.”

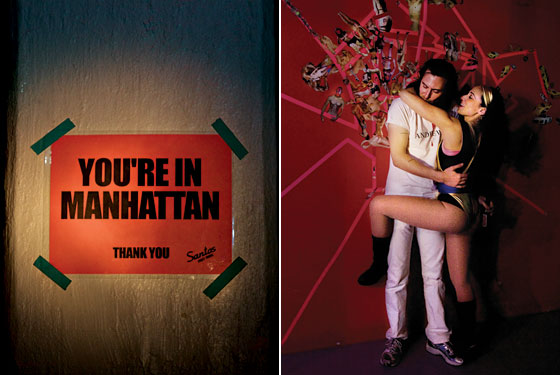

Along with his partners—the downtown artist Spencer Sweeney, the architect Ron Castellano, and nightlife veteran Larry Golden—Andrew began conceiving of Santos three years ago, long before the economy nose-dived. But their vision has proven to be almost presciently in line with recession-era New York. While Santos is a big, commercial, high-profile dance club, it has a decidedly democratic, unpretentious vibe. There are expensive drinks and a line out front, but the club isn’t defined by $900 bottles of Cristal and a bitchy door policy. Unlike Marquee and the countless other clubs that have metastasized in West Chelsea, Santos positions itself as a self-consciously friendly place, letting in anyone and everyone who believes that forgoing inhibitions is a more noble pursuit than flaunting wealth. Everything from the signs Andrew tapes to the cinder-block walls (“Thank you for partying!” “You have a beautiful face!”) to the slogans on the club’s T-shirts (“Fuck this! I’m going to Santos Party House”) reinforces the sense that the owners are very, very happy you’ve decided to come by. Like a couple of other venues—the massive, industrial-flavored Studio B in Greenpoint; legendary downtown iconoclast Susanne Bartsch’s Sunday-night parties at Greenhouse on Varick Street—Santos defines itself with a spirit of inclusivity, not exclusivity. Mainly it’s just a big, throbbing, dark room to lose yourself in for a few hours. Always eager to personify the club’s ethos, Andrew often spends hours manning the phones in the office—not something you imagine, say, Jay-Z doing at 40/40—providing directions to lost clubgoers and ending calls with messages like “Can’t wait to see you! Hope you have fun!”

While Andrew’s obsession with fun can come across as borderline comical, his unwavering belief that an awesome night can have transformative powers, providing the freedom and release required for maintaining mental health, goes a long way toward explaining why Santos has gained such a rabid and diverse following. Whereas most venues succeed by targeting a single subset of New York’s nightlife—Chloe 81 for scenesters, 1Oak for socialites—Santos aims to bring all these splintered niches together. One night it’s a destination for the asymmetrical-haircut set just off the L train, the next it’s home to a raucous gay party (Andrew: “The downstairs has been known to devolve into a kind of leather orgy”), the next it’s a techno palace, all fog machines and neon lights. “And, as you can see, Friday nights”—when the D.J. booth is helmed by the likes of Q-Tip, the rapper—“are more of a kind of hip-hop vibe,” Andrew says, proudly adding that Busta Rhymes, P. Diddy, and Mick Jagger have all stopped in. “But to me the best nights are when you see the crossover, the people who come for a live rock show and end up staying for a techno party. That’s been happening more and more.”

Up in the lighting booth, a concerned employee comes by with some earplugs for Andrew; with some reluctance, he squeezes the foam nubs into his ears. Though his celebrity is one of the main draws for Santos devotees—his performances are notoriously rambunctious affairs—to spend time with him at Santos is to understand that he has a way of quietly curating even the nights he’s not directly involved in. He designs the flyers and the drink tickets, and while he employs people to work the controls in the lighting booth, he often takes over himself. “Watch this,” he says, pressing a few buttons on the control board and throwing a cool burst of neon blue in one corner of the cavernous room, a slivery flicker of a strobe in another. “Do people notice what I’m doing? Maybe not directly, but it’s enhancing their experience. That’s all I really care about. Is everyone having the most fun they can possibly have? Is this the best night of their lives? What can I do to make it better?” As he speaks he drifts into a meditative trance, growing silent as he works the lighting for the next hour, stopping only when he realizes that the club, still packed with people, is minutes away from its 4 a.m. closing time. “Sorry about that,” he eventually says. “I get kind of possessed when I’m in here.”

When Andrew is not in Santos, he tends to be holed up in the apartment he shares with his wife, a sprightly, vivacious woman named Cherie Lily who works as a celebrity personal trainer and performs (often at Santos) a genre of dance music she calls “houserobics.” The two live on the 39th floor of a midtown high-rise, a cozy space filled with framed black-and-white posters of iconic New York skyscrapers, several of which can be seen in the sprawling views. It may seem like a curious choice of location for someone with such a downtown presence, though it doesn’t take much time with Andrew to learn that everything in his professional life, from the music he makes to the club he runs, is a way for him to participate in a lifestyle that, on a personal level, he finds fascinating but deeply alienating. Raised in Michigan, he describes himself as a socially awkward child who grew into a socially awkward adolescent and remains, his public persona aside, a socially awkward adult driven, as he puts it, by the sense of not quite belonging to any group.

“The feeling of being included or excluded—that’s always been powerful to me,” he says one afternoon, sitting inside the recording studio he built where most people would place a dining table. “By the time I got to high school I got really interested, almost out of spite, with how I could be part of every group. My feeling of revenge started to develop. The people who beat me up or teased me, I wanted to trick them by winning their approval. The feelings weren’t stemming from me feeling left out, but just feeling sad about everybody not coming together. My music was certainly based on that feeling, and the nightclub has become the pinnacle of all that.” When he first got to New York, Andrew says, “there were places where it felt like I wasn’t even welcome, like it was some kind of nuisance for me to be there.” With Santos, he explains, the idea is to create the opposite sensation, a relentlessly positive energy that specifically counters much of New York nightlife and maybe even the current mood of the country. “The club is about making people feel good about themselves. When they leave, they feel good—they got in, they had fun, they were cool. You can get a lot of power from making people feel bad, but I don’t know that it pays off in the end. It’s almost too easy, you know?”

Although his record sales are not what they once were, Andrew has continued to parlay his music career into a number of related extracurricular activities. He’s filming a game show for the Cartoon Network—“The concept is to destroy things and rebuild from the wreckage!”—and, thanks to Japan, where he remains a star, he earns a decent secondary income recording ringtones and, most recently, a soundtrack to be played on pachinko machines, a kind of anime slot machines that have given birth to a thriving culture of semi-legal gambling. But of the many unexpected tangents Andrew’s career has taken, none is more curious than his fledgling side gig as a motivational speaker. “That started in 2006, when NYU invited me to give a talk,” he explains. “I figured they wanted me to talk about the music business to, like, 45 kids, but when I got there it ended up being 900 people in this huge auditorium.” During the talk, which lasted four hours, Andrew did everything from flailing his body around spastically to singing a cappella versions of his songs to waxing philosophical about standard self-help tropes like living in the moment and being true to yourself. He has since been invited to give similar “lectures” at Carnegie Mellon and Yale and on Late Night With Conan O’Brien—many of which are in heavy circulation on YouTube.

“It’s pretty crazy,” says Andrew. “People show up to see me dance in front of a chalkboard. I don’t know what exactly they get out of it, but from what I gather it feels good somehow, and I don’t need to question it beyond that. It’s about creating a feeling of exhilaration and inspiration, a sense that you can do anything. If I go out there and make a fool of myself, then it certainly feels easier for other people to do the same, to take risks, which I think is part of the appeal.” The lectures, in other words, are best understood as an extension of the role he hopes the club plays in New York. “I’m kind of like a jester, you know?” he says. “I absorb all the fears and negative energy and awkwardness people have. My goal is to create the best feel-good feeling in the world and bring it to as many places as possible.”

On a Sunday night last month, as a foot of snow begins blanketing the city, Andrew is in the downstairs D.J. booth at Santos preparing to host a party called What the Fuck!? Wearing his trademark white jeans and white T-shirt with fake blood dripping from the collar, he is in full Andrew W.K. mode, no longer the quiet impresario in the lighting booth but the nucleus around which the party orbits. “Tonight is an experiment,” he says. “I want this club to be a safe haven for fringe performers. When I started performing, I played in all sort of places. A Starbucks. This guy’s apartment. There was a place in Ypsilanti, Michigan, called the Green Room, where there was never more than twenty people, but I pretty much created the whole Andrew W.K. thing there.” Hoping to re-create that experience, he has invited nine little-known performers to play a series of short sets. “I’m nervous about the weather,” he says. “We’ll have to see if anyone shows up.”

As the party gets under way, the prospects look grim. There are fewer than ten people gathered when the first act, a bawdy comedienne named Heather Fink, comes on. Only a few more filter in for the second act, an ironic dance-pop duo from Brooklyn called the Nuck Fuggets. Despite the meager turnout, Andrew works the audience as if addressing a packed stadium, joining in every performance while manically dancing and clapping his hands. With his voice magnified by an echo effect, he begins screaming into the microphone, issuing a number of sentiments that, for all their semi-coherence, seem to define the anxiety-annihilating role he wants the club to play. “The way we work at Santos Party House,” he yells, “is we get your pleasure in mind and then we hold it up there like a baby dove!” A few minutes later: “We’re in a blizzard, but down here we’re in a bunker of fun!” And finally: “Even in the middle of a snowstorm, and even with all the issues we’ve been facing as a country, we are all okay!”

As the third act gears up, Andrew asks the crowd for a favor. “Now I would like you to do something for me, if that’s all right,” he hollers into the mike. “I would like all of you to cheer on command. I realize that following orders isn’t always fun, but let’s give it a try! Ready?”

ANDREW: “Cheer!”

EVERYONE: “Chhheeeeerrrr!”

ANDREW: “Hooray!”

EVERYONE: “Hooooooorrrraaaay!”

As this back-and-forth goes on for a few minutes, something strange occurs: There’s a palpable shift in the mood, and … look at that! More people are coming in now, streaming in, almost as if they could hear Andrew from their apartments and figured, fuck the snow, fuck everything, let’s go get lost for a bit. By the time Andrew’s wife, Cherie, clad in a silver lamé leotard and knee-high boots, comes on, the downstairs is filled with strangers dancing together—two young girls in matching Obama T-shirts, a Williamsburg dude in skinny jeans, a jolly old guy with a video camera—all pressing up against one another, purging themselves of whatever hang-ups and neuroses were eating them up before. Though Andrew had intended the party to end on the early side, it goes until four in the morning. When he finally clears out of the club, there are no cabs in sight on the snow-slicked roads, and he and his wife have to meander through the empty streets looking for a ride home. Eventually, Andrew finds a livery cab willing to make the journey, and, content with the state of downtown for the night, he and Cherie slowly swerve their way back uptown.