Like flowers and candles, parties flare out quickly. Party designer Robert Isabell loved flowers and candles, and under his direction, they became implements of the illusionist’s art. The flowers might be tens of thousands of roses extending to the ceiling, or a single vase on each table stuffed with blooms of the same color. The candles? Maybe torches on bamboo poles swaying on the beach or silk Chinese lanterns hanging overhead as far as the eye could see.

Isabell’s parties endure as emblems of New York’s social history, iridescent bubbles of the inflating wealth of the last quarter of the twentieth century. For a New Year’s Eve at Studio 54, he snowbanked the floor with blue glitter, marking a flashy end to the seventies. The 50th-birthday party of Saul Steinberg, a financier with a renowned collection of old masters, came to represent the go-go excess of the eighties: A seventeenth-century Flemish drinking hall conjured up in a tent at a beach house in Quogue, with actors posed in tableaux vivants of great Dutch paintings. For a ball in the nineties celebrating the wedding of duty-free-shopping heiress Alexandra Miller to Prince Alexandre Von Furstenberg, Isabell created a fantasy vision of Hong Kong on the waterfront in Battery Park City.

And now? Studio 54 is long gone; its name adorns a tourist-trap knockoff in Las Vegas. The Steinberg financial empire crumbled in the nineties, and the paintings by Rembrandt, Titian, Jordaens, and Rubens went with it. The Von Furstenbergs? Divorced. In retrospect, the funny thing about these ephemeral parties is that they seem more substantial than the occasions they marked and the wealth that paid for them.

Isabell died this past July of a heart attack at age 57. Business was down, as the sinking economy made elaborate parties less fashionable: If you could still afford to celebrate, better to be understated and discreet about it. Before the decline, Isabell had tried transposing his talent as a florist into a perfume line and, later, real estate. But his uncanny sense of scale had failed him, and the pressure was intensifying. In April, he laid off half of his full-time office staff. On August 1, a huge real-estate loan was coming due. He never let on to anyone that he was even slightly worried.

Certain people, endowed with good looks, ambition, and an unthreatening charm, rise in New York as if it were a gravity-free planet. Isabell was one of those people. He was 26 when he left his job as a florist in Minneapolis to come to New York: a handsome, broad-shouldered young man with black hair, dark eyes, and a wide smile. He had grown up in a working-class neighborhood in Duluth, Minnesota, where a boy who liked flowers was an odd duck. Now, on his first night in town, October 30, 1978, he walked by Studio 54. Investigating what was causing the commotion, he was plucked from the throng by co-owner Steve Rubell and propelled inside.

Isabell found employment with Renny Reynolds, a florist whose clients included Studio 54. He was soon noticed by Studio co-owner Ian Schrager and began working directly for the club, designing flowers and décor for special events. Schrager recognized that Isabell already had an aesthetic vision and, surprising in someone so reticent, a remarkable self-confidence about imposing it. He had it back in Minneapolis, where, left alone to supervise the strip-mall florist shop in which he worked, he painted the entire window black except for one square foot, behind which he placed a single orchid on a pedestal. “In Minneapolis, Robert went through his black periods and his white periods,” says Donna Price, his best friend in those days. “When he was in his white period, he decided he was going to paint everything in his apartment white, including the floors and all the furniture. I came and helped him. Finally, he looked at me and decided I wasn’t the right color for the apartment and he put the roller on me at my head and painted white, down to my feet. I told him we were done for the evening.”

A few years after arriving in New York, Isabell pulled a similar trick at Bergdorf Goodman, where he was approached to open a flower shop that would help enliven the store’s image. “It was on a Friday, and he was going to fix his flower shop over the weekend,” says Dawn Mello, then Bergdorf’s fashion director. “I remember walking in on Monday. There was Robert, painting the main floor black. It was more than his shop. I think he got carried away.” The CEO, furious, ordered the walls restored to white. Within a few months, Isabell’s shop was gone.

But his business was just getting off the ground. In 1983, he formed Robert Isabell, Inc., and he became the city’s preeminent event designer very quickly. His Studio 54 contacts were pivotal, as was his association with George Trescher, an event planner who was trusted by the ladies who ruled New York society, from Brooke Astor and Jackie Kennedy Onassis on down. Ever since the late-nineteenth century, when Archibald Gracie King broke with tradition and gave a private ball not in his home but at Delmonico’s, New York high society was in the habit of thinking of a party in the framework of a parlor. Isabell had another idea. When he created the décor for Caroline Kennedy’s wedding in 1986, his friend Merle Gordon, who volunteered to help, overheard the mother of the bride tell the designer, “This is just like theater, but it’s only for one night.” Instead of welcoming guests into a living room, Isabell thrust them onto a stage.

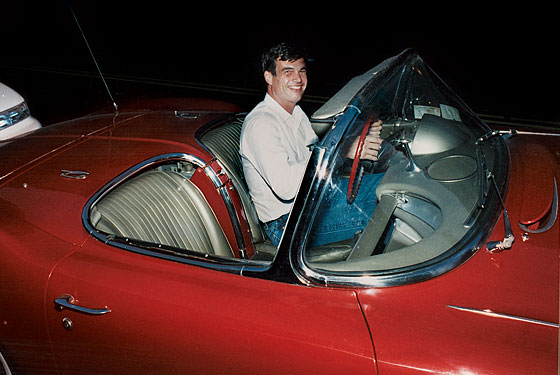

Isabell adored fireworks, baseball games, hip-hop clubs, and amusement parks. “He had a sense of wonderment with the world that many of us lose after the age of 5,” says the architect Jack Suben. The architectural paint consultant Donald Kaufman, with his wife, Taffy Dahl, met Isabell in 1981 and shared office space with him for many years. “The first car he got was a Jeep,” Kaufman recalls. “One favorite ride we had with him was in a snowstorm in Central Park. He would seek that out—‘Oh my God, there’s a blizzard, we’ve got to go to Central Park.’ Just because of the spectacle.”

Some of the excitement that New York offered was sexual. Isabell loved the Mineshaft, the most notorious of the gay clubs at the time, located in the midst of the butchers, hookers, and leather men who coexisted in the meatpacking district. It was a place where the lights were dim and the music was heavy. Men were getting fisted in slings, being pissed on in a bathtub, coupling in the dark. “That was his playground,” says artist Alexander Vethers, a close friend in the eighties. “Robert was heavily, heavily involved. One morning at 10:30, my doorbell rings and there’s Robert and he’s been out all night. I think he was more like a voyeur than someone executing things. I’m sure he participated, but that was not the main thing. He was watching. That was the way he was in life too. He was watching in order to learn.”

“I want it big and over-the-top,” said the 21-year-old Alexandra Miller. Isabell delivered.

Isabell was surrounded by people who say they adored him yet found him mysterious and unknowable. Vethers calls his connection with Isabell “the most incredible friendship I ever had,” but once it dissolved, he looked back and concluded that “after ten years, I felt I really didn’t know him.” Schrager considered himself Isabell’s closest friend. “We loved each other,” he says. “He was very, very private. He had a very compartmentalized life. There were things I didn’t know about.” After the news of the death, Schrager visited Isabell’s townhouse hoping for some sort of closure. He didn’t find it. “I went into his house to say good-bye to him,” Schrager says. “I felt I was intruding.”

In large gatherings, Isabell would usually smile, eyes crinkling, but he would say little or nothing. His inclination to deflect attention away from himself was professionally useful, because a good party planner is a little bit like a therapist: He listens. One of Isabell’s talents was the ability to divine what his clients desired from their terse or inarticulate instructions. “I want a hot, hot party,” Tina Brown told him, when she was commissioning the splashy event at the Statue of Liberty that launched her short-lived magazine Talk. “Hot.” Jackie O. was similarly pithy when planning Caroline’s wedding on Cape Cod. Pressed to say what kind of party she wanted, she finally whispered, “North Atlantic summer.” (To Isabell, that meant using only native New England flowers.)

You had to trust him, because he wasn’t good at communicating his scheme and he would usually complete it moments before the guests arrived. “Even though it frustrated a lot of clients, it did happen,” says the Glorious Food caterer Sean Driscoll, who often collaborated with him. “It happened with a little more nerves than usual.” While Isabell was able to keep to a tight budget when working with nonprofits and blue-chip corporations, most of his commissions came from the city’s more extravagant fashion, fragrance, and publishing companies, which were trafficking in glamour and willing to spend on it. Anna Wintour used him from 1995 to 2004 to stage the Costume Institute Gala at the Met. Tina Brown retained him frequently for Vanity Fair. For an event in honor of photographer Annie Leibovitz in 1991 at the New York Academy of Art, Isabell complemented the building’s classical statues with nearly nude models that he had painted off-white and dressed in bits of starched muslin. He covered the floor with white tile, draped the walls with white fabric, created towering pyramids of white roses, and lit everything with a cool, bluish light.

The best clients, though, were private ones, who did not have to justify their personal expenditures. One of Isabell’s favorites was Gayfryd Steinberg, who attracted much unflattering press attention for two high-priced Isabell parties in the late eighties: the wedding of her stepdaughter, Laura, to Jonathan Tisch at the Metropolitan Museum, for which the flower bill alone was said to be a million dollars, and her husband Saul’s 50th-birthday party in Quogue in 1989. The tent in which the birthday dinner was served had been rigged with thick wooden beams. And the tableaux vivants that were ridiculed in the press were ravishing: brilliantly staged renderings of iconic paintings such as Rembrandt’s Danae and Vermeer’s Milkmaid. “Those Flemish faces aren’t wandering all over New York,” says Karin Bacon, whose events company found them. They were lit and framed in ten arrangements around the room. “With someone like Robert, they have a vision, and they will compromise only so much,” Steinberg says. “He had a very nice way of managing that. He said, ‘Yes, yes, yes,’ and pretty much ended up doing it his way. And his vision was probably the best vision.”

Isabell’s signature clients of the nineties were two of the three daughters of billionaire Robert Miller. He first met the youngest, Alexandra, who retained him for her 21st-birthday party in 1993 at the Rainbow Room, with a Roaring Twenties theme. “I wanted it big and over-the-top,” she recalls. Isabell delivered. Alexandra introduced Isabell to her mother, who thought of him belatedly in 1995, with the July wedding in England of her middle daughter, Marie-Chantal, to Crown Prince Pavlos of Greece a month away. She had already been through four designers when she called Isabell with a nagging anxiety. “The last designer had said that they needed this much fabric for a 40-meter-by-70-meter tent, and was that enough?” recounts Isabell’s technical director, Liz Garvin, who overheard one end of the conversation. “Robert sat in the office with his calculator and worked out the numbers and said, ‘No, it isn’t.’ She asked, could he come help her right away? He said, ‘I’ll take the Concorde and be there tomorrow. Get me a room at Claridge’s, and we’ll put this thing together.’ ”

The Mineshaft was his playground. He loved to watch.

A month later, his self-assurance was vindicated. For a Thursday-night welcome dinner at the Wrotham Park estate outside London, Isabell devised a steel structure in the form of a Greek temple, with a floor of hand-stamped cork, a false linen ceiling, and pillars and a cornice that seemed to be made of marble. When cocktails were finished, a white curtain behind the pillars was pulled back, and the 800 guests walked through the arch to dinner, where big urns on laurel-wrapped pedestals each contained thousands of yellow and orange Ecuadoran roses (Mrs. Miller is a native of Ecuador). The lights that illuminated the field behind the tent were so extensive that they could have been mistaken for a flight runway and had to be cleared with Heathrow. Much of the scenery was fabricated in this country and transported to England by an art shipper. The cost of the dinner and the Hampton Court luncheon that followed was reported to be $5 million.

Isabell tried over the years to find a business more durable than party planning. His first attempt seemed logical for a florist: perfume. He was obsessed with making a product that didn’t smell artificial. Instead of mixing fragrances from essential oils, he found a Swiss chemist who had devised a way to replicate natural scents, and he began flying to Switzerland every month. He packaged his perfumes in lab-style bottles of extruded optical glass that he designed. And when Perfumes Isabell launched in May 1996, he insisted on a series of unconventional marketing decisions: releasing five products at once, rather than building up his brand with a single initial offering; setting up a toll-free number for direct sales; and, two years later, launching isabell .com, which was in the vanguard of Internet shopping.

To be his co-CEO, Isabell brought in Matthew Bronfman, of the Seagrams family; as with most of his wealthy friends, he had first met Bronfman professionally (in this case, as a wedding designer). But the partnership soured, says Dallas Haden, an industry veteran who was enlisted by Isabell as a fragrance-marketing consultant. One of Haden’s initial tasks was to tone down Isabell’s business plan. “Part of my job was to bring some reality to Robert’s goals,” she says. As the business played out, however, it fell short even of scaled-down ambitions. Within a couple of years, Isabell was drawing back from the company, and eventually Haden acquired the brand herself. “He really thought it would be a fantastic success, and it was disappointing,” says the artist Jennifer Bartlett, a close friend of Isabell. “But he would never show his disappointment. Robert was not a complainer.” In a very nineties segue, he moved on to real estate.

The starting point of Isabell’s fascination with real estate was probably the house he bought on Minetta Lane in 1990. It was a dump: a three-story building with a carriage house in the rear. But he liked the gritty location—although his clients were white-bread and upper crust, his own taste in culture ran more to hip-hop and salsa, and his taste in men to the type who played ball at the fenced-in court around the corner on Sixth Avenue—and he was taken with the idea of transforming the place.

“We were there the first night he got it,” Donald Kaufman says. “Literally, Robert, my wife, and I started the demo ourselves, with sledgehammers, taking out walls. That’s how he did everything: instant action. Then, after a lot of walls were knocked out, he brought in an engineer. They looked around. The guy said, ‘I’ve got some ideas, but we’re going to talk about it out on the street.’ ”

The house he created (after some structural stabilization) was not cozy and domestic; there was no kitchen. Instead, it was like an Isabell party, in which you moved from one space to the next, encountering different magical environments. He connected the front and rear buildings with a glassed-over atrium, 65 feet high, which he filled with bamboo and palms, and spanned with a floating staircase that could be lit with votive candles. Kaufman remembers visiting one night and hearing a funny sound: It was a team of Tibetan-born sherpas from Brooklyn, enlarging the basement by hand-chipping the walls.

That same year, Isabell installed his business in a small building on West 13th Street that he purchased for $975,000. Admiring how his friend Schrager evolved from a disco owner to a hotel designer and real-estate developer, he tried for many years to develop the property. In 2006, he bought the mirror-image property to the south on Little West 12th Street for $7.5 million, so he could build out the block and lease high-end retail and office space in a new building. The neighborhood had been designated a historic district in 2003, which meant he needed—and won—the approval of the landmarks commission.

Isabell was transfixed by the game. “I’m getting bored,” he told his architect, Suben, as the project neared completion. “I have to look for more property.” What he found was 837 Washington Street, a run-down building that was one door up from the old Mineshaft, shuttered long ago. Envisioning a studio building for photographers and event designers, Isabell told Suben that the meatpacking district was the only recession-proof neighborhood in the city.

He bought 837 Washington for a mind-boggling $45 million last year, at the peak of the market. He planned to build a 50,000-square-foot structure on the site, but again was dependent on the landmarks commission’s approving his plans. “I told him, ‘If Landmarks doesn’t give you what you want, there’s no nice way to put this, Robert, you’re screwed,’ ” Suben recalls. “He said, ‘It’s not going to happen.’ ”

Over the last decade, Isabell found an unconventional soul mate in Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon. A close friend of Jackie Kennedy who redesigned the Rose Garden of the White House in 1963, Mellon is an heiress to the Warner-Lambert pharmaceutical fortune and the widow of philanthropist Paul Mellon. Isabell first met her at Caroline Kennedy’s wedding, and their friendship deepened after Paul’s death in 1999.

They shared a love of flowers (she has one of the largest gardening libraries in private hands), but their relationship quickly branched out. They spoke twice a day. “His way of looking at everything was completely unique,” says Mellon, who is 99. “He would come down here to the country, two or three times a month, with armfuls of flowers. He was elusive and very, very attractive.” For her 90th birthday, he surprised her with a party at her house on Cape Cod. In a field of wildflowers he placed an enormous four-poster bed with curtains blowing in the wind and pillows all around for people to sit. At the edge of the woods he hid an orchestra.

Friends were bemused, bored, or delighted when Isabell would natter on rapturously about Mellon’s 2,000-acre Virginia farm. She is a charming paragon of old-money style and a fount of horticultural knowledge; to be welcomed into her circle of intimates was a signal achievement for a high-school graduate who hailed from the wrong side of Duluth. Isabell planned to build himself a house on her property and some day help run her horticultural foundation. In his will, after some bequests to friends and relatives, he left everything to the foundation.

As a scheme for his future, the Virginia plan was more auspicious than his real-estate predicament back in New York. He and Suben made multiple approaches to the landmarks commission, seeking approval first to tear down the existing two-story building at 837 Washington, then to preserve it and add four stories of glass and ivy-covered steel on top. Landmarks demurred each time. In March, the head of the commission informally indicated that they would permit nothing higher than a four-story building on the site.

Isabell was facing an August 1 deadline to repay a $48 million loan—at 20 percent interest—or he could lose all his property. He had no tenants for 410 West 13th Street, and rents in the city were slipping. Even though he had been soliciting party business abroad, from the royal family in Saudi Arabia and the casino-owning Lawrence Ho in Macau, among others, he watched as budgets for many of his New York clients shriveled.

Suben says that despite “signs of stress from time to time” that caused “little flare-ups,” Isabell maintained an outward cheer. A week before his death, pink and white impatiens appeared as if by magic one afternoon to blanket the metal canopy of 837 Washington. “We had gone to a meeting out on Long Island, and he came back and put that up, maybe because the High Line was going up and he wanted people to have something pretty to look at,” says Joe Heffernan, Isabell’s second-in-command. It was a final characteristic gesture of gratuitous beauty. Although he couldn’t add four stories to his building, no one would stop him from festooning it with flowers.