In the fitful, politically motivated, often deceptive process of rebuilding the World Trade Center site, at least and at last the news about the memorial is good: A very promising design, the best of the eight finalists, won. Entrants—5,201 of them from 63 countries—submitted proposals to commemorate 9/11, and after the finalists were announced in November, a thirteen-member jury picked Reflecting Absence, an inspired plan of quiet dignity and apparent simplicity by Michael Arad.

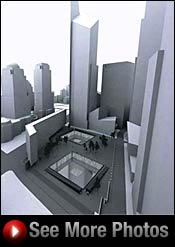

The young New York architect, who lives in the East Village and works for the Housing Authority, focuses on the footprints of the Twin Towers, and within their square perimeter depresses reflecting pools, an acre each, 30 feet below. Sheets of water pour continuously down the interior façades of each basin. In the middle of the planes of water, Arad sets another pool, creating a second void. Visitors follow ramps angled down the side of each footprint to an underground chamber that allows views through the veils of water. Names of all the victims, including rescuers and those who died in the 1993 Trade Center bombing, are inscribed on a knee-high wall between the chamber and the pool.

This is a bold design not because it is aggressive but because the architect has taken charge of the entire block bounded by Greenwich and West streets running north-south, and Liberty and Fulton, running east-west. One of New York’s most captivating characteristics is the street-side buzz of cars and people, but for the memorial to succeed—for visitors to sense the enormity of what happened those hours that morning—the architect has cleared the deck and cleansed the urban palette, creating a flat plane of stone stretching from street to street. Between all the present and future towers, Arad carves out a space of visual silence.

The boldness is in not only the vision itself but Arad’s insistence on a buffer zone. To achieve the quiet, he removes Daniel Libeskind’s proposed museum structures, which encroach on the square and even bridge one of the footprints. Arad also fills in the famous bathtub that was the cornerstone idea of Libeskind’s project.

We have come a long way since the days a memorial meant a triumphal arch or a man riding a horse. Maya Lin, a member of the WTC memorial jury, fought that battle decades ago in Washington when she wedged her triangle of polished stone into the earth and inscribed the walls with the names of America’s Vietnam dead. Some veterans wanted statues in the heroic tradition of marines raising flags. Lin’s design, establishing an evocative and contemplative environment, forged an alternative path, and Arad’s design clearly belongs to that young tradition. He has not created an object that dominates space or a symbol that tells people what to think, but a setting that plunges us into an immersive, reflective experience. As visitors embark on their journeys, their senses and thoughts are focused by an environment that scopes down in ever sharper focus on the inescapable fact of absence, monumentalized by the square, gigantically empty crater. He creates an abstract dreamscape in which to wonder.

The chair of the jury, Vartan Gregorian, has called the void “inconsolable.” Not quite. Standing in a darkened chamber ringing the huge well, visitors will look through the sheets of water into a void that leads the eye, redemptively, to sky and light. But Gregorian is correct in the sense that the journey down the ramps is a path into mystery. With great clarity, Arad has counterintuitively cultivated the sense of the unfathomable—that it is difficult to put our minds and hearts around the events of that day. He has mystified the site.

Many relatives and friends of the victims have lauded the design for its simplicity and dignity. As many think otherwise: too bland, too minimal, too cold. This is still a work in progress, and an evolved scheme is to be unveiled the week of January 12. Arad has been joined by eminent landscape architect Peter Walker, presumably to soften the hardscape with greenery. But a critical moment in creating a work of art is knowing when to stop. The quality that enables this plan to work is the visual Zen: Just a few elements work together to create the void and the path into it. The ramps, with their tilting roofs, challenge our sense of equilibrium and tell our bodies that an event disturbed this land. Too much green could look like a visual apology for an idea that needs none.

The real undeveloped potential of the scheme is the possibility of spiraling the ramps down even farther into the earth, to the stumps of the original columns remaining in bedrock, where so many of the victims were crushed. If the functional demands of the underground program are moved elsewhere, Reflecting Absence could descend to this final level, to inner sanctums under pools illuminated by light penetrating the water, rippling. One immovable impediment is the path line, which runs along the edge of the south footprint.

Arad has reportedly carved an underground corridor between the two footprints, and a chamber for the families in this underworld. Starting with ancient Egypt, architecture history is rich in precedent for underground rooms. In the coming weeks, families concerned about the ultimate cemetery of their relatives will be watching to see how the architect can bring bedrock into the plan.

The design may appear simple, but Arad proposes a highly sophisticated orchestration of elements—water, light, space, sky, earth—that capture the absence and the sense of loss. But the degree to which this memorial will haunt us depends on such details as how the water will form continuous sheets, the precision with which the standing water meets its edges, the rim of the second pool set within the first (it could look like a hole mysteriously cut in the water).

This is a place of shadows and whispers. Even a huge monument to absence is hugely fragile. The vision must be cultivated until it is exquisite—and then protected. The success of Arad’s plan lies in the godly details.

Related Story

What do you think of the proposed WTC memorial?