Karole Armitage is 49 now. She no longer blazes hell-bent across the stage in her own choreography, she’s quit cranking up her music to total-annihilation decibels, and since 1989, she’s spent most of her time in Europe. In short, she’s handed in her title as downtown’s punk ballerina. But when she unveiled her latest work with the ad hoc company she calls Armitage Gone! Dance at the Joyce earlier this month, there was no mistaking who was in charge. Armitage grew up in ballet, then became a prized Merce Cunningham dancer; her choreographic style was forged in the rigor shared by both traditions. You see technique, you see horsepower, and you see plenty of attitude—her favorite decorative element. In the new, hourlong piece, the dancers slash their way through exaggerated splits, sky-high extensions, and deliberately ostentatious posturing, glowing every moment in a hard, gold light. It’s Cunningham more than anything else, but it’s Cunningham that’s been through the fiery furnace.

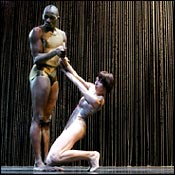

Time Is the Echo of an Axe Within a Wood (the title comes from a poem by Philip Larkin and probably should have stayed there) takes place in a wonderfully arresting space created by the artist David Salle and the lighting designer Clifton Taylor. The stage is hung on three sides with curtains made of trembling, shimmering chains that fly out when the dancers pass through them, as if to suggest that some sort of magic lurks in the mysterious border between dancing and not-dancing. The company is made up of a dozen dancers of wildly different sizes, shapes, and backgrounds, including several described as “self-taught.” They tend to emerge and disperse in waves, yet each performer works most often in fierce solitude, even in the midst of duets or group passages. Movement is frequently wielded like a weapon here: Many of the duets are bouts of pure combat, though the dancers seem fixed on attacking the music, not each other. In quieter sections of the piece, it’s a relief to see partnering that describes a relationship rather than a coincidence.

“Many of the duets are bouts of pure combat, though the dancers seem fixed on attacking the music, not each other.”

Armitage has spiked the choreography with bits of yoga, bharata natyam, and voguing, but of these only the last, with its defiant self-consciousness, slips into place as if it belongs there. Yoga and bharata natyam are about transcendence; they’re techniques that reach to a state beyond exertion, and there’s nothing in the well-organized frenzy of Armitage’s work that doesn’t relish the superficial as an end in itself. This quality is exacerbated by the fact that she’s oddly unmusical. The piece moves from Bartók to the contemporary composers Gavin Bryars and Annie Gosfield, and ends with Ives’s The Unanswered Question, but only the most obvious qualities of the music seem to interest her. A punk sensibility doesn’t provide much of a training ground for depth or nuance. Armitage has moved well beyond her days of rebel chic, but she seems unwilling to take the next, riskier step—to quit demanding an audience’s attention, and start earning it.

Paul Taylor has been earning it for 50 years now, which is why his audience lovingly forgives him when, once in a while, he doles out utter nonsense. I don’t mean the truly great nonsense, like Dreamgirls; I mean the dances in which you can almost hear Taylor wondering Why am I still doing this? as he choreographs. On opening night of his annual City Center season, for instance, we got Le Grand Puppetier—a new take on Stravinsky’s Petrushka and a pointless one, apart from the chance to see Patrick Corbin, as the clown, brilliantly demonstrate once more how dancing can create character without surrendering the purity of the steps.

The other New York premiere was In the Beginning, which has more clarity and wit but certainly doesn’t leave you with the sense that Taylor has a whole lot to say about Genesis. He offers Adam and Eve, paradise and expulsion, and a torrent of begats—their offspring and their offspring’s offspring scramble into life through Adam and Eve’s widespread legs—while an unpredictable Jehovah keeps changing his mind about what he’s created. Accompanying these goings-on are excerpts from Carmina Burana, fortunately rendered in a minimally orchestrated version without chorus. In this format, Orff’s music is quite bearable—simple and childlike—but if you loathe Carmina Burana, it’s impossible to tune out what you know is horribly there. Both these new works are cartoon visions of control and rebellion, power and punishment—Taylor’s own wry view, perhaps, of half a century running a dance company.

The good stuff was in the older works, including Aureole, which was premiered in 1962 and gleams today like well-polished silver after being performed thousands of times all over the world. It’s still a dance that throws off revelatory moments with every bar of Handel’s music, and the marvel this time was Richard Chen See, jumping so lightly and precisely through the footwork here he might have been springing on clouds, yet expansive and powerful in his bearing. Piazzolla Caldera, Taylor’s 1997 fantasy on the tango, spirals right through all the conventions, emotions, and melodrama associated with the tango without ever actually showing one. Silvia Nevjinsky and Michael Trusnovec were especially glorious as they preened themselves in an extravagant soap opera of a duet.

Last season’s masterpiece, Promethean Fire, returned as the climax of this year’s opening-night benefit performance, which is understandable but at first seemed too bad. After that long business with the Stravinsky puppets, it was hard to regroup for one of the most serious and commanding dance works of our time. Even so, the instant the company appeared in a cluster onstage, looking straight into disaster without flinching, the audience was suddenly still. Not a sound was heard for the length of the dance. Taylor’s genius hardly needs confirming, but if he can tame the restless partygoers on a benefit night, clearly he can do anything.