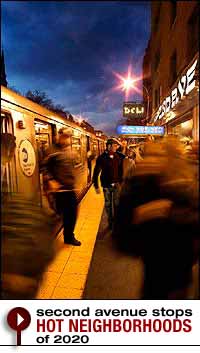

Beloved, believed in, glimpsed fleetingly only to disappear again for decades, the Second Avenue subway has long seemed to be New York City’s version of the Loch Ness monster. The plan has been on the drawing board since the year Babe Ruth hit his first home run for the Yankees—that is to say, since 1920, when it was envisioned as part of a massive subway expansion that brought us the IND, the trains that now run under Sixth and Eighth avenues. But the Second Avenue subway was derailed by the Great Depression, and despite a string of vigorous efforts, the plan just never got back on track.

That, however, may be about to change. The Second Avenue subway is surfacing again, and this time the vision of a new line just may finally be realized.

The project is suddenly enjoying a perfect storm of favorable circumstances. Peter Kalikow, the MTA’s chairman, is committed to expanding the system in a way not seen since—well, not since Babe Ruth hit his first home run for the Yankees. Some of the money is already secured: The MTA has a quarter of the $4 billion or so it needs to launch the first leg. Meanwhile, federal officials are bullish on the plan, partly as a result of lobbying by Kalikow, a major GOP fund-raiser, and many believe the federal government will soon commit to paying at least a third of the first portion’s price tag.

Finally, a big political obstacle has been removed: Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, whose district is on the Lower East Side, is telling colleagues that he’s ready to support the plan even if the MTA decides to begin uptown. “I am flexible on doing stages as long as there’s the understanding that we’ll ultimately do a full build,” he says.

Sure, hurdles remain—it has to clear a final environmental review, and state and federal officials have to actually come up with the money, not just talk about it. But with Silver and Kalikow squarely behind the project, and consensus emerging among pols and civic groups (the Straphangers Campaign, the Regional Plan Association) on how and where to start it, the Second Avenue subway may be closer to reality than at just about any time during its tortured 84-year history.

“We can really build it in our lifetime,” says Mysore Nagaraja, the MTA’s chief engineer charged with overseeing construction. Nagaraja, a slight, bespectacled man with the calming presence of a pediatrician, often hears colleagues joke that he should take a long look at the sun now, because he may spend the next decade or so underground. “You may have a dream, but is it realistic?” Nagaraja wonders aloud. “This is realistic. It’s really buildable.”

With luck, and a last-minute burst of political will, the MTA could break ground as early as next year on the biggest subway expansion in 60 years.

If you want to know why the dream of a Second Avenue subway line has endured, take a ride on the 4 train at 8:30 a.m. on a workday. If MTA rush-hour stats are to be believed, you’ll be sharing a train car with around 180 commuters. While on the West Side there are two and sometimes more lines, on the East Side, the Lexington Avenue line has borne the burden alone since the Third Avenue El came down in the mid-fifties. On any given weekday, the Lex carries 1.5 million passengers, more daily riders than the metro systems in Washington, D.C., Boston, and Chicago—combined.

The Second Avenue subway would change that. The northern terminus would be at 125th Street and Lexington Avenue, allowing proximity to Metro-North, with its connections to Westchester. After traveling down Second Avenue, the line would fork at 65th Street. One line would curve west, to the F-train station at 63rd and Lexington, where it would join an already built tunnel linking to the Broadway N and R lines. The main stem, meanwhile, would continue down Second Avenue to the financial district. The cost of the entire project (which wouldn’t be complete till 2020) would be more than $17 billion, requiring construction of 16 new stations, as well as 28 sophisticated new trains that can travel closer together, thus easing congestion even further.

The MTA wants to build the line—which would ultimately be 8.5 miles long—in small, financially realistic stages. Although the MTA is considering other options, the first portion would likely start at 96th down to the 63rd Street station, where it would join the rest of the system.

The first leg will likely require the drilling of a shaft some seven stories deep into Manhattan at 96th Street and Second Avenue. Then a monstrous tunnel-boring machine—nicknamed “the Mole” by tunnel pros—would be lowered to the bottom. The Mole will inch forward, its spinning blades dislodging chunks of prehistoric bedrock—1.5 million cubic yards of it in phase one—after which the tunnel will be shored up with concrete lining.

The Mole is a technological breakthrough. It enables tunneling to go on far beneath the surface with little impact aboveground, unlike the old “cut and cover” technique, which tore up streets. “We can tunnel without disturbing buildings,” says Nagaraja. “People in the buildings won’t even feel it.”

That’s not to say there won’t be any serious disruptions. The drilling of the shaft would close a lane or two on Second Avenue in the Nineties. And then there are the new stations, which would be built inside existing buildings—not on sidewalks—meaning major problems for those who live or work in those structures. Whole shops are likely to vanish. You might want to drop by for a last look at the Food Emporium supermarket at 86th Street, or the Falk Drug and Surgical Supply store, at 72nd. They’ll likely be gone in a few years, condemned and replaced by state-of-the-art subway entrances. “It’s not a good feeling to think you have to leave the place you’ve been in for 50 years,” says Perry Falk, the drugstore owner. “This has been our home forever.”

And yet there appears to be little organized resistance thus far. “The subway is something that the overwhelming majority of East Siders want,” says Charles Warren, chairman of the Upper East Side’s Community Board 8. “The opposition we’ve seen so far is really to the location of stations, not to the project as a whole.”

The slow, fitful progress of the Second Avenue subway began on an early spring afternoon in 1925, in a park in Harlem, when New York’s mayor, a pasty-faced pol named John Hylan, raised a silver pickax above his head and plunged it into the sod beneath his feet.

He was breaking ground on phase one of a massive new IND subway system that would allow the city to tear down those nineteenth-century relics—elevated tracks—that blocked out sunlight from Manhattan’s major thoroughfares. The Second Avenue line would be phase two of this grand expansion.

Hylan hoped that his swing of the pickax would strike a great blow on behalf of the city’s people against their oppressors: the private companies that ran the IRT and what would become the BMT. Hylan called them “grasping transportation monopolies,” because they refused to risk profits expanding into new residential frontiers. The IND—the first municipally owned line—would challenge their hegemony.

Related Story

Underground Man

By Craig Horowitz

Real-estate tycoon Peter Kalikow is rewriting his legacy by presiding over the biggest expansion of New York’s transit system in 60 years. And the Second Avenue subway is only part of the MTA chairman’s paln. (April 4, 2004 issue of New York Magazine)

Phase one was built during the mid-thirties, but cost overruns and the Great Depression postponed phase two. In 1941, the hated Second Avenue El was torn down, leading residents of Yorkville to parade in the streets. A new underground line couldn’t be far behind, it seemed—but World War II suspended all construction.

The Second Avenue subway landed on the front page of the Times in 1950 when Democrat Ferdinand Pecora made it an issue in his mayoral run. He lost, but subway overcrowding remained a popular fixation, and a year later, New Yorkers approved $500 million in government bonds for the project. Officials quietly spent most of the half-billion dollars on repairs. When news leaked that the money was gone and there was still no subway, a furor erupted. “It is highly improbable that the Second Avenue subway will ever materialize,” the Times lamented.

A decade later, with conditions on the Lex already intolerable, two men relaunched the project: Nelson Rockefeller and MTA chairman William Ronan, a self-styled Moses-like master builder. In 1972, Rockefeller, Ronan, Mayor John Lindsay, and a young congressman named Ed Koch journeyed to 102nd Street to break ground.

As reporters scribbled, Lindsay drily noted that in the twenties, “some people suggested a transit facility along Second Avenue. And it was such a good idea that I decided to follow up on it immediately.” The pols took their swings with a pickax—but in an uncanny piece of symbolism, none could dent the pavement. A worker with a power rig was called in to break the concrete.

To be sure, workers did build three segments of tunnel—between 99th and 105th streets, between 110th and 120th, and another downtown. But then the seventies fiscal crisis shelved the project yet again, and by the eighties, the MTA was running newspaper ads offering to rent the tunnels to private companies. “I remember being asked by a magazine, ‘What should we do with the excavations?’ ” Koch says. “I proposed growing mushrooms in them. Mushrooms need a dark interior.”

This legacy of failure has meant that New York, a city that prizes all things new and current, has a transit system that was last expanded around the time Paris fell to the Nazis. “The list of new mass-transit projects built in other world cities in recent decades is incredible,” says New York subway historian Clifton Hood. “But here, we’re still riding around on a system built by our great-grandparents.”

For the first time since Rockefeller and Ronan, the Second Avenue subway has two powerful patrons on the state level: Assembly Speaker Silver and MTA chairman Kalikow, a real-estate magnate who’s spent a career building big projects.

Silver has been widely hailed as a Second Avenue subway hero since 1999, the last time the MTA passed a five-year capital plan, when he threatened to block a host of big state projects unless funds for the line were included. The MTA put $1 billion in its budget—a substantial sum still waiting to be spent. Silver’s leverage is again at a maximum, because the MTA this winter will pass its next five-year plan, and Governor George Pataki wants to please his suburban base by funding East Side Access, a tunnel linking the LIRR to Grand Central Terminal. That gives Silver a chance to play let’s-make-a-deal with Pataki and, if necessary, do what he did last time: hold up other big projects—like East Side Access—to win another burst of state funds.

Kalikow, meanwhile, is the first MTA chairman in a generation who badly wants the project to happen; his recent predecessors were too busy rescuing the system from crime, graffiti, decay, and declining ridership. He has been aggressively lobbying (and throwing private fund-raisers for) U.S. senators like Richard Shelby and Patty Murray, who wield influence over transportation funds. Kalikow is engaged in other intricate behind-the-scenes politicking: He’s told colleagues that he may try to use $600 million in funds already earmarked for a train to La Guardia airport (a plan with an uncertain future) for the Second Avenue subway. That may lead to a clash with City Hall, which is likely to want the cash for extending the 7 line west.

There are reasons to be optimistic about the Feds. In a barely noticed development in February, the Federal Transit Administration put the plan on its short list of projects being considered for funding. That’s a big deal, because FTA money comes from a pot of federal dough separate from funds overseen by Republicans who are trying to rejigger transit funding to shaft the city. FTA bucks are less captive to partisan wrangling and actually tend to be doled out to projects based on the merits. The FTA likes the Second Avenue subway because it would serve more than 500,000 and has broad support among New York pols.

Kalikow vows that FTA funds are all but secured for the first leg. “I’m completely confident we will have funding from the federal government by the end of the year,” Kalikow says. If the FTA chips in at least $1.2 billion, and Silver secures another $1 billion, the MTA, with $1 billion already on hand, will be in striking distance.

“If the stars aren’t already aligned right now, they’re pretty damn close,” says Elliot Sander, a senior VP at DMJM+Harris, which would help build the first part.

The Second Avenue subway has its share of high-powered skeptics, to be sure. Michael Bloomberg, for instance, seems far more interested in the 7 line. And the Partnership for New York City, a group of 200 top CEOs, recently slammed the plan, arguing that the new line’s economic benefits didn’t justify its enormous cost.

“Outside of another politically untenable fare increase,” says Partnership CEO Kathryn Wylde, “the business community does not see where the money will come from to pay for the state’s share of projects such as the Second Avenue subway.”

Silver and Kalikow beg to differ.

The Second Avenue subway would alter life in East Side neighborhoods from Harlem down to Alphabet City. Residents would, for the first time, be spared the notorious trek to the Lex line that is known to real-estate brokers as “the walk.” As Regional Plan Association president Robert Yaro points out, the new subway would also grow the so-called hospital corridor—the big medical institutions along Second Avenue in the Twenties that are driving the city’s health-care industry.

It would transform the real-estate market. Pamela Liebman, CEO of the Corcoran Group, predicts it would produce an immediate jump of at least 10 percent in the value of apartments east of Second Avenue from the Nineties down to the Lower East Side. “It would open up the possibility of more luxury housing east of Second Avenue,” Liebman says. “It would stimulate commercial development the whole length of Second Avenue, bringing in a whole new wave of support services.”

Subway construction has often brought gentrification in its wake—the Sixth Avenue line sparked the long-term transformation of a low-slung working-class neighborhood into a wall of office towers—and the Second Avenue line would offer its own twist on the phenomenon. It would further inflate land values in upper-class Manhattan neighborhoods (notwithstanding the grumbling you occasionally hear in the luxe enclave of East End Avenue that the new line would bring in the sort of people current residents moved there to get away from). While some might find themselves priced out of Manhattan as a result, the new line could also stimulate economic development in low-income neighborhoods like Harlem and spur economic expansion in ways that, in the long run, might lift the whole city.

Just as the subways built from 1900 to 1940 shaped the city’s growth through the twentieth century, so a Second Avenue line built now, at the outset of the 21st, could help drive the city’s growth for the next hundred years. The city’s future could hinge on its ability to move people into its ever-expanding business district, and eventually, the Second Avenue line could even revert to its original purpose: a trunk line for a whole new train system. Some planners, thinking deep into the future, envision it as a jumping-off point for subways into neighborhoods in the eastern Bronx and possibly in central Brooklyn—the neighborhoods that could absorb the workforce of the future.

One person who’s thrilled by that prospect is Nagaraja, who’s looking to earn his place in the pantheon of great subway builders. At a celebration of the subway’s centennial, he found himself entranced by a large picture of William Parsons, builder of the first subway line. “One of the people who was with me commented that when they celebrate 200 years of subways, instead of Parsons’s picture, there will be your picture,” Nagaraja says, without a trace of irony. “I feel very proud of that.”