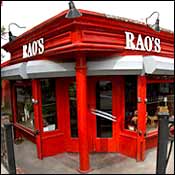

The way Louie tells the story, he hadn’t intended to shoot the guy in the back. Louis Barone, as the police would identify him, Louie Lump Lump to those who knew him from 116th Street, said he hadn’t even planned to bring the five-shot Smith & Wesson to Rao’s that night. Not that Rao’s was off-limits for weapons. Wasn’t that part of its charm? Rao’s, with all of eleven tables, is located way up in exotic East Harlem. “Who eats in Harlem? Who even goes to Harlem?” said one restaurateur. And yet the place was nearly impossible to get into—Madonna was, famously, turned away. And some fraction of the draw was, as one Mafia lawyer put it, the “patina” of danger—in a safe way, of course. Part of the charm, in other words, was that a Louie Lump Lump might be at the bar. As one titillated downtown PR exec explained after a night at Rao’s: “I hugged one guy and I could feel he had a gun on his waist, and then I hugged another guy and felt his gun. The place is a pisser.”

Louie hardly thought in those terms. For him, Rao’s was an old-time neighborhood place, and Louie was an old-time neighborhood guy. He’d been going to the family-owned restaurant for 40 years, since Vinnie Rao presided in the kitchen wearing his famous cowboy hat. He’d known co-owner Frank Pellegrino, Vinnie’s nephew, since Frankie was a teenager with his heart set on a singing and acting career. Louie liked to walk down the four steps, past the Madonna in the window—the only Madonna who could get in—make a drop, as he’d say, spend a few bucks on a drink at the dark-stained oak-paneled bar with the red leatherette pad. He’d never be without cash in his pocket—at Rao’s a guy might tip $20 on a $30 bar bill. But if he had ready money, the bar at Rao’s was a place to run into old friends, say hello to the bartender Nicky the Vest, so-called because of his 142 vests.

Now and then, Frankie would even throw him one of those impossible-to-get tables. (He’d had one a week after his 67th birthday, November 14. He’d waited four months for it, and he took three acquaintances who’d begged him to get them in.) Louie had a lot of respect for Frankie and for Rao’s. Some people said that respect was one of those values that had, like Louie, seen better days. Even with mobsters—selling one another out for book deals—respect wasn’t what it used to be. But the way Louie would later frame the story, respect was one of those neighborhood things that counted with him. Could it be, as Louie would have it, that in his aging person, respect was about to take a last shot?

As a young man, Louie had made a living doing construction. Twenty years ago, though, Louie hurt his knee—in conversation, he pulls up a pant leg to show off three long scars. He’d been on disability ever since, which was how he supported himself. That and running numbers. As for the gun, Louie had carried one off and on for years. He’d been busted for carrying one after a club he was in got tossed—he beat that rap claiming an illegal search. He’d been arrested a couple other times, including ten years ago, on a gambling charge. It never amounted to much. Louie had never been sentenced to more than a year in prison.

By now, most of the guys Louie had grown up with—he’d lived in an apartment on 116th—had moved out of the neighborhood, which had been Italian before going Puerto Rican. Even Frankie now lived in Nassau County. Louie had first moved to an apartment on East 75th, a sweet rent-controlled deal. Then half a dozen years ago, he bought a real nice co-op on Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, two bedrooms, for a monthly nut of $660, including—and this really appealed to Louie—indoor parking for his two-year-old gray Dodge sedan. Louie was not a public-transportation guy.

Later, Louie would tell the cops that he’d decided to carry the gun that night because of the Orange Alert, “a white lie” in Louie’s mind. In truth, sometimes he just felt better with a gun on him—“if I get a feeling,” he said—which probably wasn’t unusual for a numbers guy. Louie swore that he wasn’t a made guy, not a Mafia soldier—Louie acted as if that idea was laughable, a guy like him. Just ask his girlfriend. Louie has had the same girlfriend for decades. She chuckled at the thought of Louie as a big-time gangster. Still, to run numbers you’d have to be associated, and a former FBI agent said his association was with the Lucchese crime family.

For Louie, crime was a bit of a family vocation. The cops also knew Louie’s father, who they said had a Genovese association, and his brother. In fact, they knew his brother much better. Paulie “Fats” Barone ran wire rooms, where he took sports bets. Louie gave the impression that his brother was the successful sibling. His brother was the one throwing a Christmas party just up the block from Rao’s. Louie was, he said, getting by. Between disability and numbers, and watching expenses, Louie said he managed to keep his nose above water, which he indicated by placing a level hand to the tip of his nose.

That night, three days before Christmas, Louie took a seat at the far end of Rao’s small bar—it had only about eight stools—near a framed article about Nicky the Vest in Bartender magazine. Louie, at 67, was five eight or so. He had thick, steel-gray hair covered with a cap that said NASSAU, BAHAMAS, as if, maybe, he’d just come back from a cruise. He had a fleshy nose and a body shaped like a torpedo, an extra 30 pounds around his middle. By coincidence, Louie’s first cousin was at a table—a legitimate guy also named Louis Barone. (The two Louis Barones had promised to catch up.) So was Sonny Grosso, another ex–neighborhood guy and the ex-cop whose life had been made into the movie The French Connection. Now Grosso produced TV. Michael Amante, the tenor who’d recently performed at Town Hall, was there with his wife, a former Miss India. Johnny “Roastbeef” Williams, visiting from L.A., had wandered in with his daughter. He was another ex–neighborhood guy—he’d owned delis, including Johnny’s Super Hero, which accounted for his nickname—who’d gone into the movie business. He was an actor.

That night, Louie, his gun in his right pants pocket, took a seat next to a younger guy—30 years younger than Louie, it would turn out—a well-built six-footer wearing a black leather jacket. This guy—Nicky the Vest called him Al—had been to the bar a few times in the past six months. He was with a friend, running a tab. He had cash, but no wallet on him. Louie didn’t know him, he said. The guy was from out of town and, according to Louie, was definitely not showing the proper respect.

Years ago, Rao’s was known as a joint where mobsters went—when the actor Michael Nouri, who will star in the upcoming revival of Can-Can with Patti Lupone, played Mob boss Lucky Luciano, Frankie showed him Luciano’s table. Mob bosses Paul Castellano and John Gotti had dined at Rao’s over the years—“Somehow they got a table,” griped one regular—as had Tony Salerno, who used to run the neighborhood for the Genovese family. (Even he apparently had trouble getting a table. One story has it that Salerno kidnapped Rao’s chef and installed him at another restaurant to avoid the ordeal.) When he was a cop, half-Italian Bo Dietl had been listed as Mob-connected just for drinking at Rao’s.

Rao’s, with its dark wood and perpetual Christmas lights, is still one of those places where a wiseguy looks right. At Rao’s, a wiseguy can be a wiseguy; called by his nickname, kissed on the cheek, sitting on a stool, fat as a house. At least he can be taken for one. And how many venues—outside the movies—offer such quality showcasing? (Even the movies headed to Rao’s to nail the type. Martin Scorsese cast six Rao’s regulars in GoodFellas—including Johnny Roastbeef, who let Warner Bros. use his name in the film.) The real-life mobster, the scary one, might seem part of a time capsule—Mob movies are likely to be kitschy and comic these days—but Louie Lump Lump didn’t think so. He was old enough to have spotted Lucky Luciano at Rao’s. Rao’s was the place he wanted to go.

Of course, these days Rao’s is the place everyone likes to go—Billy Crystal, George Pataki, Rod Stewart, Dan Marino, Woody Allen, Robert De Niro, Sophia Loren, to name a few—and very few can. There are just those eleven tables. Plus, Rao’s closes on weekends, doesn’t serve lunch, and has only one seating a night. Once, State Supreme Court Judge Edwin Torres, who wrote the book that became the movie Carlito’s Way, tried to bring the movie’s director, Brian De Palma, and its producer, Martin Bregman. Torres, who’d grown up in the neighborhood, was a Rao’s regular. Frankie said no. He almost always said no—his nickname is Frankie No. “Where am I going to put them?” Frankie asked Torres. (A well-known photographer got a table on his birthday, but he, at least, had the good sense to ask a year in advance.)

Frankie is, by most accounts, an accidental restaurateur. He loves acting—he’s a recurring character (an FBI agent) on The Sopranos—and has a movie-producing company with a friend from Rao’s. When an aunt died, he fell into the Rao’s business, which he enjoyed, though, honestly, even he didn’t quite understand the restaurant’s popularity—“I’m in awe of the phenomenon,” he’d tell regulars. It was not a happy situation. He had lots of friends he couldn’t accommodate. He was embarrassed to go to friends’ restaurants. Get treated nice, and then? He couldn’t invite them to his place. As he told one friend, if he ate out, it was Chinese.

Eventually, to deal with the crush, he’d come up with an idea. No reservations. Instead, he assigned people regular tables, once a week. Now and then they gave their tables back for Frankie to dispose of. Otherwise, the table was theirs, bring who they want. At what other restaurant did a person “own” a table, like a condo? From Frankie’s point of view, though, it was a lot less of a headache.

Ron Perelman, chairman of Revlon; Tommy Mottola, former head of Sony Music; and Bill Rollnick, former chairman of Mattel, got tables. “It’s my greatest asset,” said Rollnick, which was only half a joke. (On hearing that Sophia Loren wanted to come, Rollnick got to bring her.) For years, Dick Schaap, the late sportswriter, had a table. During his eulogy at Schaap’s funeral, Billy Crystal wondered, “Who gets his table at Rao’s?” (His wife got it.)

A table at Rao’s was a valuable thing. At an auction, one brought $20,000—not including food. But money was only one way to value a regular table at Rao’s. Rao’s was outside the chain of celebrity command. Bill Clinton, Bill Gates, Jack Welch, Al Pacino, Bette Midler, had been there, but they couldn’t get reservations on their own. William Friedkin sat at Sonny’s table. Jack Welch sat at the table of Bo Dietl, another ex-cop with movie connections—a movie was made of his life story, One Tough Cop. “I put together a Who’s Who,” Bo said of his table. Bo invited Donny Deutsch, Steve Witkoff, Ken Langone, captains of business who might not naturally have hung out with the street-smart Bo from Queens, now a private security specialist who dressed so expensively that he sometimes spelled his name Beau. But Bo controlled an interesting bit of New York real estate—Bo, in fact, said he’d had his table built specially to accommodate a couple more places. And this got to the heart of the Rao’s phenomenon.

Frankie distributed table privileges based not on financial heft or Q rating but, for the most part, on loyalty. He favored longtime customers, regular people. “Not powerhouses,” said Rollnick. “We’re Frankie’s people.” And so, unexpectedly, the gatekeepers to the exclusive realm weren’t the Robert De Niros of the world—he’s never had a regular table. (Even when Mia Farrow was researching a movie role by studying Frankie’s aunt, she came as a guest.) Often, table owners are former neighborhood people, regular guys, with local accents. So even if you’re one of the world’s biggest pop stars or you’ve just won the Super Bowl, to get into Rao’s it helps to know Ralphie from Queens who sells outdoor advertising or the guy from Jersey who sells latex for swimsuits, both of whom own tables. “Unknown, outer-borough people,” said Betsy McCaughey, who as Betsy McCaughey Ross served as Pataki’s first lieutenant governor and who’s been a guest at Rao’s a few times.

Sonny Grosso jokingly put his finger on the gatekeeper’s power: “I went to high school with Regis Philbin, and I always tell him, ‘I don’t care how much money you have, you can’t get into Rao’s without me.’ ” (Though, apparently, he tries. Michael Nouri, who sometimes uses Rollnick’s table, says, “Regis has called me. The poor bastard just can’t get in.” )

Probably the oddest part of the Rao’s experience is that, despite the dense packing of celebrities, it’s not cool in a contemporary sense. The place is a throwback. It doesn’t even look like it belongs on the contemporary restaurant scene. David Rockwell didn’t have a hand in the design. After a fire about half a dozen years ago, Rao’s hired a set designer to help re-create its Christmas-in-the-boroughs look. The walls are dark wood, the ceilings dark tin, and Christmas trim hangs year-round. The place doesn’t have a coat room—there’s a rack near the men’s room not far from a jukebox, most of whose songs date from 30 or more years ago. Rao’s has published a successful cookbook, marketed a delicious pasta sauce, but there’s no star chef.

People don’t idle their limos outside of Rao’s for adventurous Italian cuisine. It’s Italian home cooking. “This is just like the food my mother used to make,” Pacino told his host on his first visit.

Night after night, Rao’s offers a Sunday Italian dinner, blue-collar, familiar, approachable (once you’re in), and for the downtown set, the moviegoing class, the Wall Street gang, the Hollywood crowd, it’s exotic, fun, slightly embarrassing, and, what with some of those torpedo-shaped guys at the bar, titillating, too. (“Frankie don’t want to put down the B.S. about what people find interesting, and he don’t want to promote it either” was how one regular put it.) At Rao’s, men kiss each other hello, Italian-style, and call each other by those nicknames. The atmosphere isn’t heady or rarefied. Introductions get made—Michael Amante met the record exec who’d sign him to a CD deal at Rao’s. Still, you don’t imagine intellectual chat. Every now and then deals get brokered—Bo swears that he and Stevie Witkoff put together a deal to buy the Woolworth building at his table—but the real angle “is showing a potential partner who could not get in an entrez-vous,” as Bo put it.

Unusually, what people experience at Rao’s, with its fifties décor, its feudal loyalties, with Frankie No, the restaurateur-as-Godfather, is that it’s fun. They say that as if they’re unaccustomed to fun, at least the Rao’s strain, which may be true. Stars don’t control the room. Storytellers do, especially those with a connection to the neighborhood or the street. Bo, Glock on his waist, tells his table about catching a nun’s rapist. Or Sonny, .38 on his waist, tells his table about connected Joe Rao, Vinnie’s brother, attending his father’s funeral with two “tree trunks.” He had them bend at the casket.

Then at some point in the evening, Frankie, who started as a singer and now makes a pretty good living as an actor, punches up his favorites on the jukebox. Frankie is charming—people love him. He’s almost always the best-dressed guy in the room: beautiful suit, cuff links, pocket spot. As the music starts, he weaves figure eights around the room’s few tables with their white tablecloths. His voice is airier now, his voice box damaged. But he sings with feeling, shouting out his favorite lines in his few favorite songs. When Bill Clinton visited Rao’s—he went with Jon Corzine, borrowing Dick Schaap’s widow’s table—Frankie directed “My Way” to him. “Mistakes, I’ve made a few,” Frankie sang to the former president, who buried his face on the table, playing along.

The night that Louie Lump Lump Barone sat drinking at the end of the bar, a couple of guests got up to sing, too. Michael Amante, a powerful tenor who sang to Sophia Loren at Rao’s (she kissed him “on the lips,” Amante recalled), sang “O Sole Mio.” The crowd cheered. Then Rena Strober stood up. She’s 27, attractive, and had recently sung in Les Miz. She sang “Don’t Rain on My Parade.”

Which is when, according to Louie’s story, the trouble started. Next to him sat that guy wearing a dark leather jacket. Albert Circelli had been to the bar at Rao’s a few times in the past half-dozen months. Al, as he was called, was 37. He was from Yonkers, where organized crime was controlled by the Luccheses, though crime there could be unorganized as well. (A few years ago, some of Al’s contemporaries, sons of local Mafiosi, went wild, robbing and murdering, when they weren’t hanging out at the local mall. Anthony DiSimone, whose father reputedly ran a Lucchese crew, murdered a kid outside a Yonkers bar. Apparently he felt protected by family connections.)

Al had a modest house on Landis Place, a working-class section of Yonkers that goes in for big Christmas decorations. Al, who lived with his mother and grandmother—his parents were separated—and a German shepherd, had a couple of giant candy canes just inside a chain-link fence. A neighbor said he’d seen Al walking the dog, cutting the lawn, and thought him a pretty good neighbor. An attorney said Al had been involved with Xpress Ambulette service, though that company was no longer in business. For a time, he may have worked with a family exterminating company. He wasn’t a college grad. Laurie Brasco, an ex-fiancée who lived with him five years ago, called Al a homebody. “Boring,” she said. “That’s why I had to leave.” He had home-remodeling projects, liked to cook on Sundays, and loved to work out. He’d eliminated salt, sugar. “He was six one and really built. He killed himself,” said Brasco. “Not an inch of fat.” They’d stayed friends, though she didn’t know how he earned a living now.

Law enforcement, though, had Albert J. Circelli Jr. down for a different sort of life. They pegged him as a recently made Mafia soldier, a member of the crew run by Anthony DiSimone’s father. “Sources in the organized-crime law-enforcement circles reported that Circelli was a soldier in the Lucchese crime family,” said Joseph F. O’Brien, a former FBI agent and co-author of best-seller Boss of Bosses. If he wasn’t connected then, some wondered, where did he get the cash for all those fancy cars? He had eight cars registered to his name: five Cadillacs, a Chevy, a Ferrari, and a Lincoln. That night, he’d taken the Lincoln to Rao’s, where parking was always available.

Louie, who was said to have his own, less formal, association with the Lucchese family, would later say he was sure that Al was a Mafia soldier. “He had his button,” Barone would say, which was a way of saying that he’d been inducted. “I’m sure he was a wise- guy.” If nothing else, there was the way he mouthed off, as if pulling rank. A lady was singing. Rena Strober stood a few feet away.

“Not this fucking broad again. Get her out of here,” said Al.

Louie felt sorry for his girlfriend, even the parentsof the victim. Then he said: “I’m deeplysorry to have done that at Rao’s. Please tell Frankie.”

Louie put a finger to his lips. “Show some respect,” Louie told Al. In Louie’s telling, he was sticking up for a lady, for himself, for the values of the neighborhood and of a place like Rao’s.

It was about 10:30, the time the crowd starts to thin out. Sonny Grosso was outside retrieving a Michael Amante record for Len Cariou. Johnny Roastbeef had also stepped outside. He was checking his messages. Cariou, who’d recently been in Proof on Broadway, had the table right next to the bar. His grandson and granddaughter were with him. His bill had arrived—it’s close to $1,000 for an eight-person table at Rao’s. He was writing out a check.

Louie says he heard Al say something to him after he put his finger to his lips. “I’ll break that finger off and shove it up your ass,” Al said. Nice talk. It didn’t stop there. “I don’t care who you are and who you’re connected to, I’ll take care of you,” Al supposedly said.

It was, in theory, the kind of exchange that an outsider might travel up to a place like Rao’s to overhear. This was no tidy downtown snub. It was a street beef, the kind that earned Louie his nickname—for the lumps he got and those he received. A young Mafia buck, feeling his Cheerios, issued an insult, one that in this neighborhood with its ominous history, its sensitivities, its codes, inevitably drew a response. Louie liked the version in which he played the honorable older gentleman. But also, anybody who knows him knows he has a temper. He could go ballistic losing a bet on a football game. And, of course, Louie could be fluid with the truth. He wasn’t worried about terrorists, despite what he’d said.

Still, to a lot of people, what Louie contemplated hardly made sense based on ruffled honor. Louie had a practical side. He wasn’t a big-shot gangster, or trying to be one. He was 67, thought about getting by, always had. He’d once dated a great girl twenty years younger, but wouldn’t marry her because he figured, What about when he was in his sixties and trying to keep up? Louie wasn’t the kind to overreach. He liked low monthly payments, indoor parking, a girlfriend his own age.

To Louie, another issue seemed to be in play. Al was a big guy, physically big. He understood Al’s words as a very specific threat from a connected guy. “There was fear,” Louie would later say. “I was scared.”

Al Circelli asked Nicky the Vest for the check, threw down some cash. A moment later, Louie reached into his pocket for his .38. In the movie, the next bit would have happened in slow motion. Louie shoots from the hip, not even getting up from the stool, not aiming at Al’s back. It’s a quick gesture. Al doesn’t even see the gun. “He spun off the stool,” Louie said. That’s how he got him in the back. Albert Circelli, hit once in the heart, stumbled twenty feet toward the Madonna in the window, where he fell at the feet of a diner, Al Petraglia, chief clerk of the Nassau County Surrogate’s Court, who grew up with the other owner, Ron Straci. Louie followed Circelli, cruising on that bum knee. He shot again, and missed—“Nerves,” he explained—and instead hit Petraglia in the foot. He tossed the gun aside, pushed out the door. Cinematically, it was perfect. A pool of blood, and the singer who hid under a table.

Louie bumped into a couple of uniformed cops—“there’s been a shooting inside,” he told them. But an off-duty cop eating at Rao’s came up behind him, gun drawn. Sonny, the ex-cop, rushed toward the door. “I think the cop recognized me,” he said. Like in French Connection days, Sonny helped nab the hood.

Pellegrino ran over to Cariou’s table, tore up his check, then helped Cariou get his grandkids, one of whom was stricken by an asthma attack, to Metropolitan Hospital, where Petraglia soon followed. Frankie was beside himself. One diner remembered him with his head in his hands.

Not that Frankie for a moment imagined a murder would hurt business at Rao’s. The following Monday, seven days after the shooting, the place was jammed. The bar was three deep. All the tables were taken, despite the fact that it was a couple days before New Year’s and many regulars were out of town. Sonny, in fact, said that he’d gotten more requests than ever. “Hillary’s people called,” he said. She wanted to go to Rao’s. The dark room with the low tin ceilings was lively, maybe livelier. At Sonny’s table, Judge Edwin Torres—he’s working with Bregman on a prequel to Carlito’s Way—was talking about the defendant in his courtroom, a guy who sawed off victims’ heads then moved into their apartments. Apparently he did this three times; each time, said Torres, he went after people who lived in one particular line. “He liked the G line,” the judge said in amazement. Sonny, who wore jeans, and a friend bantered about whether he’d stolen missing French Connection loot. (“No,” said the friend. “He’d dress better.”)

In a few minutes, Michael Nouri headed toward the jukebox to sing “O Sole Mio.” He pushed past Sonny, who obligingly offered Nouri his pistol for protection, just in case. But as Nouri announced, “No one is going to tell me I suck tonight.” Which was true, because when Alex Rocco—he played Moe Greene in The Godfather, a character who got shot in the eye—got up to sing and did suck, there was applause all around. Except from Bill Persky, producer of TV shows like Dick Van Dyke, That Girl, and Kate & Allie, who yelled, “I’ll shoot you in the eye.”

It was a good room. People were having fun. Crime, Mafia, gossip about Louie Lump Lump seemed, if anything, to have goosed the crowd. Neil Leifer, the sports photographer—he took the famous photograph of Ali standing over a defeated Liston—was there with the writer Frank Deford and Mark Shapiro, an ESPN honcho. Dan Marino, the former Miami Dolphins quarterback, was at a booth. Someone wanted him to sing. “All I know is the Dolphins fight song,” he shouted. Frankie, though, will sing. Frankie’s acting career has been great. He worked for Woody Allen and Martin Scorsese, Rao’s customers. Right now, though, he put his all into a song that, though he sang it all the time, seemed especially meaningful tonight. He sang “My Girl,” and, as always, everyone in the room joined in, even Marino. “Don’t need no money, fortune or fame / I’ve got all the riches, baby, one man can claim.” Frankie leaned into this last line and, pointed at the floor, as if to say that that line applied to his restaurant, and to all his good friends, those who’d made it in the door. Then, song over, he leaned over a guest’s shoulder. “This is the real Rao’s,” he said.

In jail, at the Bernard B. Kerik Complex, Louie wore a gray jumpsuit. Ever practical, he hoped his girlfriend would bring him some sneakers so he could start to exercise on the roof. He needed to lose some weight. He couldn’t stand the food, but the other inmates treated him well. “Like your style,” they told him, which seemed to amuse Louie. They treated him like a Mob hit man, like he was the last defender of Mob courtliness and action.

For his part, Louie worried if he’d ever get out of jail. The D.A. wasn’t impressed by his tale. “He killed a guy,” one assistant D.A. said, as if to say, end of story. Still, Louie hoped he had a shot at manslaughter. The old numbers guy was doing the math. “I could get out when I’m 74 maybe, still have a few years left,” he said.

Thinking about his girlfriend, whom he’d known for so long, Louie got tears in his eyes, especially when he heard how upset she’d been. He even thought about the parents of the guy he killed. Mainly, though, Louie’s remorse ran in one direction.

“I am deeply sorry to have done that at Rao’s,” he said. “Please tell Frankie.” Louie paused. He did seem sorry, charmingly, authentically sorry. Then he talked about other things. He wondered about subletting his co-op, and how he could deal with getting permission from the co-op board. It would be nice if he could sublet the place. He’d just given his lawyer $10,000. He could use a little extra income.