The Murdoch-ization of America has never felt so irreversible. At any given moment, according to Business Week, one in every five households is tuned into a show produced or delivered by News Corp.; meanwhile, Fox News is crushing CNN, the Weekly Standard is running the Bush administration, and three of the top six books now on the New York Times’ best-seller list were published by Regan Books. And in perhaps the most unmistakable sign yet that New York’s preeminent right-wing robber baron has become an entrenched member of the city’s Establishment, Rupert Murdoch recently purchased the late Laurance Rockefeller’s Fifth Avenue triplex for $44 million. In cash.

New York existed before Murdoch. But unlike the staggered, crisis-plagued ascent of fellow tycoon Donald Trump, his rise has been so steady that it has come to appear almost inevitable. It’s easy to forget that his entry into American consciousness was a reckless bet on the future of New York.

The year was 1976, and evidence of the city’s decline was everywhere: subway cars bruised with graffiti, arson fires that swallowed whole ghetto blocks, soaring murder rates, and annual six-figure job losses. The city put on its best face for the Democratic convention, hastily enacting an anti-loitering law that enabled cops to round up most of the prostitutes in the vicinity of Madison Square Garden. For a few days anyway, even Times Square was more or less hooker-free. But the area soon returned to being America’s most infamous erogenous zone.

Around the country, cartoonists poked fun at New York in its apocalypse: The city was a sinking ship, a zoo where the apes were employed as zookeepers, a stage littered with overturned props. Central Park had become a running joke in Johnny Carson’s nightly monologues (“Some Martians landed in Central Park today … and were mugged”). The syndicated columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak understated the matter considerably when they wrote, “Americans do not much like, admire, respect, trust, or believe in New York.”

It’s easy now to look back at this moment and see it for what it was—a classic market bottom. But at the time, few recognized it as such. One man who did was Murdoch. Where others saw a city in financial distress, he saw a place ripe for entrepreneurship. Where others saw a failed experiment in social democracy, he saw an opening for simple supply-and-demand capitalism.

Murdoch fixed his sights on the once-proud New York Post, which would become the beachhead of his American conquest. It was there that he perfected the mix of hard conservative politics and unapologetic tabloid values with which his name would become synonymous. How long did it take to create a template for the world we’re living in? About three months: the strange, violent summer of 1977.

When news of Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of the New York Post first hit the Daily News and the New York Times—the sleepy Post had been scooped on its own sale—on November 20, 1976, the city’s response was a collective “Rupert who?”

He’d materialized in New York overnight: a thick, sad-eyed, harried-looking fellow with an outsize head and furry eyebrows, more day laborer than press lord by the looks of him. Murdoch’s father, Sir Keith, had been a legendary newspaperman himself, the proprietor of a chain of Australian dailies that were meant to be son Rupert’s inheritance. Only, by the time of Sir Keith’s death, the family had been forced to sell off almost everything, leaving Rupert, at the age of 22, a single provincial afternoon paper called the Adelaide News. In short order, Murdoch turned it into a thriving scandal sheet, and a tabloid career was launched.

By 1968, Murdoch had extended his nascent newspaper empire to London, where, among other gifts to the culture, he inaugurated the custom of running photos of topless women on the third page of his newspapers. Private Eye, the British satire magazine, dubbed him “Rupert ‘Thanks for the Mammaries’ Murdoch.”

In 1973, Murdoch made his first foray into the United States, snapping up a pair of broadsheets in San Antonio. When the news there failed to rise to the level of drama that he liked, he goosed a headline or two. KILLER BEES HEAD NORTH was one classic; the story that ran beneath it was about a species of bee with a potentially fatal sting that had been spotted minding its own business somewhere in South America.

The following year, Murdoch leaped into the world of supermarket tabloids with The National Star. He was just getting started. Installing his second wife, Anna, and their three children in a twelve-room Fifth Avenue triplex, he kept shopping. After briefly considering a few women’s magazines, Ladies’ Home Journal and Redbook among them, he decided on the Post, the oldest continuously published daily newspaper in America, one of the last living links to the country’s Founding Fathers.

By the time Murdoch arrived on the scene, the paper was in the possession of one Dorothy Schiff, who had taken it over in 1939. Initially, she’d bankrolled it for her husband, until she grew tired of him and his dilettantish editorial instincts. Schiff dumped him and turned the Post into a tabloid; through the forties, it came into its own. Under the editorship of James Wechsler, the paper specialized in crusade reporting, taking aim at the mighty Robert Moses, uncovering the human cost of his “slum clearance,” and at J. Edgar Hoover, who subsequently ordered Wechsler’s hotel room bugged and labeled him a “little rat.” The Post published a seventeen-part exposé of the foremost demagogue of the day, Senator Joseph McCarthy. Headlined SMEAR, INC.: JOE MCCARTHY’S ONE-MAN MOB, it was the first in-depth look at “the hoax of the century.”

The Post published the great Murray Kempton, whose columns seemed to embody best the paper’s ethos, its commitment to ennobling the struggles of the working class, while keeping a keen eye on the rich and powerful. It was also the paper of “It Happened Last Night,” the gentlemanly gossip columnist written by “Midnight” Earl Wilson. “Nobody ever feared me,” Wilson once boasted.

Through the sixties, Schiff embraced the emerging ways of the tabloid, a whole new approach to fashioning narratives. Tabloids were passionate, dramatic, melodramatic. Even when big issues were at stake, tab stories had to be driven by larger-than-life characters and defining details.

In December 1962, a citywide strike upended the New York newspaper world. Four major dailies died in its wake, and the Post would have keeled over, too, if Schiff hadn’t broken ranks with her fellow publishers and negotiated her own settlement with the unions. (Murdoch pulled exactly the same stunt in the summer of ’78.) In 1967, when the Post’s last afternoon competitor folded, the paper’s circulation nearly doubled to 700,000.

But the good times didn’t last. The Post grew dowdy in its dotage. Schiff’s cheapness was partly to blame; among her memorable cost-cutting measures was the mandate that reporters obtain prior approval before placing overseas phone calls. While the rest of the media were busy discovering the new celebrity culture—Time Inc. launched People, Andy Warhol launched Interview, the Daily News hired people-spotter Liz Smith—the Post was still clinging to Midnight Earl and his jocular chitchat about the Great White Way.

It’s hard not to read something else into the paper’s aimlessness. The trauma of the Lindsay years had eroded New York’s civic culture, which the Post had so assiduously nurtured with its expansive liberalism. By the mid-seventies, New York’s middle class was becoming increasingly conservative. Somewhere along the way, the Post had lost its raison d’être, and Rupert Murdoch, who, like any self-respecting publishing tycoon, yearned to sink roots in New York, had apparently found his.

Murdoch first met the Post’s silver-haired doyenne in the summer of 1974, at the East Hampton beach house of New York Magazine’s founder, Clay Felker. Murdoch could be charming, particularly when he smelled a bargain. Like a young couple eyeing a widow’s gracious, if dilapidated, Park Slope townhouse, he recognized the Post as a blue-chip property that had just about bottomed out. Schiff, who’d been married and divorced four times and still smoked Kools through a white cigarette holder, was not immune to charm, particularly when her seducer’s sweet nothings included attacks on the New York Times.

The first time Murdoch asked Schiff about buying the Post, she turned him down. But after the paper logged a substantial loss in ’75 and was en route to an even bigger deficit in ’76, Schiff, in the fall of that year, invited Murdoch to lunch at the Post’s shabby downtown digs. The two publishers sat at her luncheon table and ate roast-beef sandwiches on rye bread—Schiff served corned beef to Jews, tuna to Catholics, and roast beef to Protestants—beneath a life-size papier-mâché statue of Alexander Hamilton. “I sensed that she was very tired,” Murdoch later reflected. Within three months, they had settled on a $31 million price tag.

Murdoch went off to a private dining room upstairs at ‘21’ to celebrate with twenty of his most trusted colleagues. The corks were still popping come midnight. The group eventually stumbled downstairs and found Governor Hugh Carey and Tip O’Neill, who would soon become speaker of the House, at the bar. Murdoch and his crew joined them for a drink. James Brady, the editor of The National Star, suggested that they finish the night at Elaine’s, where the media elite always finished its nights.

As was the custom, a few stretch limos were grazing in front of ‘21,’ hoping for some freelance fares. The Star’s ace reporter, Steve Dunleavy, suggested that they travel uptown in style. Murdoch shook his head; taxis would be cheaper.

“But, boss,” pleaded Dunleavy, “you just spent $30 million on the Post. For once, let it be limos!” And it was.

The few who were familiar with Murdoch’s history were skeptical, but for the most part, New York, a city of subway readers, gave him a warm welcome. “New York hasn’t had a first-rate newspaper rivalry since the Great Strike of 1962,” wrote Michael Kramer in More, a respected, if short-lived, journalism review. “And now, thanks to Australian newspaper magnate Rupert Murdoch, the good old days seem to be on their way back.”

And what of Murdoch’s briny recipe for success—the blood, the guts, the boobs? That would never play here, Kramer, More’s editor, confidently predicted. “His mix for the Big Apple is going to be a good deal more sophisticated.”

Not long after assuming control of the paper, Murdoch had stood in the Post’s newsroom and assured his staff that he had no dramatic changes in mind. “Don’t judge me by what you’ve heard about me,” he said. “Judge me by what I do.”

The first sign of change had been harmless enough. On January 3, 1977, Murdoch added a thick red stripe to the Post’s otherwise black-and-white front page. That same day, “Midnight” Earl Wilson finally got some company: “Page Six.” In its first month, “Page Six,” a gossip column assembled by a team of reporters, spotted Woody Allen canoodling with a “very young girlfriend” at Elaine’s; reported that Dorothy Hamill was carrying on with Dean Martin’s son, Dino Jr.; and quoted Muhammad Ali saying that he’d like to star in an all-black remake of Ben-Hur.

Murdoch was an active presence in the newsroom, writing and rewriting headlines, even answering telephones. Men with Australian accents—“gangaroos,” as veteran Posties called them—were soon roaming the paper’s halls too. They liked the feel of the city, and they loved that the pubs stayed open past 10:30. But they had a lot to learn about New York. One of the new editors, Peter Michelmore, asked veteran reporter George Arzt about the ethnicity of the staff.

“We’re mostly Jewish,” Arzt replied.

“I haven’t met many Jews,” said Michelmore. “We were always taught that they had horns on their head.”

“Mine are retractable,” answered Arzt.

The most reviled of Murdoch’s new editors was Edwin Bolwell, a squat Aussie prone to shouting and turning red in the face. Among other ignominious acts, Bolwell decided that the reviews by the Post’s young film critic, Frank Rich, were “too windy” and ordered them halved.

Beame called Murdoch an “Australian carpetbagger” who “came here to line his pockets by peddling fiction in the guise of news.”

Topless women, it was decided, wouldn’t fly in New York, but that didn’t rule out cheesecake. In March 1977, the Post ran 21 items on Farrah Fawcett-Majors, the feather-haired star of Charlie’s Angels. Stories became shorter, pictures bigger, headlines louder, the news more ideologically charged. The Post hammered away at what it perceived as New York’s permissive criminal culture, fronting a photograph of Alice Crimmins, a cocktail waitress who’d been sent to jail for killing her two children, enjoying her weekend furloughs on a yacht. On the eve of the execution of serial killer Gary Gilmore, the first person put to death in America in more than a decade, a peaceful protest took place in front of his Utah penitentiary. This is how the Post played it on the front page: THREAT TO STORM GILMORE PRISON.

Then came the blackout—and New York’s first real taste of what Murdoch could do with a major news event. On July 13, 1977, Con Ed lost power and plunged the city into darkness. The lights went out around 9:30 at night, and within minutes, there were reports of looting. Violence would end up striking every borough, but damage was particularly severe in poor neighborhoods like Bushwick, Brooklyn, where virtually every single store was gutted and burned.

The city struggled to make sense of the carnage—was this a cry for help from neighborhoods buckling under the unfair burden of unemployment and disinvestment? Had the safety net failed?

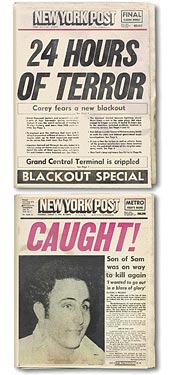

The Post felt no ambivalence whatsoever. The riots, in the paper’s plain view, were the handiwork of criminals running free under the cover of darkness. Murdoch came into the paper’s un-air-conditioned office at dawn after the blackout and quickly sweated through his white dress shirt. The power outage prevented the Post from publishing that afternoon, but the paper’s “Blackout Special,” with the front page blaring 24 HOURS OF TERROR and a pullout section headlined A CITY RAVAGED, was on the streets the following morning to stoke the anger and fears of its readers. An editorial blasted the police commissioner for his “absurd order to go slowly … as the mobs ran wild.” The Post also invoked the blackout from 1965 to suggest that conditions in the city were worsening. “In ghastly contrast to 1965, when a spirit of unity and common sacrifice brightened every section of the darkened city, New York was transformed into a series of seething battlegrounds.”

To Osborn Elliott, whose job as a deputy mayor was to attract business to the city, the real disaster wasn’t the looting. It was the New York Post’s coverage of it. Elliott dispatched a letter to Murdoch. “So your New York Post has now covered New York City’s first big crisis since you took over,” wrote Elliott. “Are you proud of what your headlines produced?”

Mayor Abe Beame denounced Murdoch too, calling the paper’s arriviste publisher an “Australian carpetbagger” who “came here to line his pockets by peddling fiction in the guise of news.” The Post, the mayor continued, “makes Hustler magazine look like the Harvard [Law] Review.” Pete Hamill also laid into Murdoch, comparing him to a guest who vomits at a dinner party: Everyone looks at him with alarm and pity, but no one knows quite what to do with him. “Something vaguely sickening is happening to that newspaper,” Hamill wrote in the Daily News, “and it is spreading through the city’s psychic life like a stain.”

Murdoch himself could not have cared less. The Post’s July 15 “Blackout Special” exceeded the paper’s usual Friday sales by 75,000. His tabloid—and his Hobbesian view of the city—was starting to catch on.

As if the blackout weren’t enough diversion for one summer, New York was also contending with a serial killer. Here again, Murdoch seized the opportunity to frighten and soothe, and to define the city on his terms. For a newspaperman, it was hard to imagine a better story. A killer with a .44-caliber pistol was hunting young women and leaving notes for the police signed “the Son of Sam.”

The Post was initially slow to react to the story. But after getting his clock cleaned day in and day out by Jimmy Breslin and the Daily News, Murdoch jumped into it with a vengeance, throwing his fellow countryman Steve Dunleavy into the hunt for Sam. Lanky and pasty-faced with a gravity-defying pompadour, the 38-year-old Dunleavy had come to New York via Fleet Street ten years earlier. He drank vodka tonics with the expat journalist crowd at Costello’s on the East Side, but Dunleavy was different from his fellow hacks at the bar. Aside from his right-wing politics, he was, as Mario Cuomo described him to The New Yorker many years later, a real New Yorker at heart: “He’s feisty, he’s resilient, he’s self-made, he stands up for what he believes in, and he can even, on occasion, be charming.”

As of July ’77, Dunleavy had been at the Post for less than a year, but he already had a reputation. “Steve drank a lot and fucked a lot,” remembers his managing editor, Robert Spitzler. Legend has it that one winter night, after doing quite a bit of the former, he and a Norwegian heiress were engaged in the latter when a snowplow ran over Dunleavy’s foot. He was so busy pumping away that he scarcely noticed. “I hope it wasn’t his writing foot,” Pete Hamill quipped.

Dunleavy went after the Son of Sam story with a similarly single-minded lust. Along the way, he produced a few legitimate scoops and yards of grisly, overwrought copy. What he lacked in police sources, he made up for in imagination. One day Dunleavy took a tape of the Jimi Hendrix song “Purple Haze” to an “audio expert” on Madison Avenue who amplified the lyrics. Someone was apparently singing, “Help me, help me, help me, Son of Sam,” in the background. LYRIC MAY YIELD SON OF SAM CLUE, explained the Post headline.

By the middle of July, the NYPD’s Son of Sam task force was receiving a thousand tips a day. Every hour, a thousand more callers couldn’t get through because all twelve hotlines were busy. Women were naming husbands, ex-husbands, and boyfriends as suspects.

The Post wasn’t quite breaking news, but its fevered attempts to do so forced the Daily News into playing the same game. On July 28, the day before the anniversary of the first attack, the News advertised Breslin’s Son of Sam column on its front page. Breslin dedicated the column to the killer on the occasion of “his first deathday” and resurrected the letter the killer had written him almost two months earlier, quoting one especially newsworthy passage: “Tell me Jim, what will you have for July 29 … You must not forget Donna Lauria and you cannot let the people forget her either. She was a very sweet girl but Sam’s a thirsty lad and he won’t let me stop killing until he gets his fill of blood.” Breslin couldn’t help wondering: “Is tomorrow night, July 29, so significant to him that he must go out and walk the night streets and find a victim?”

The Post answered the following day with a page-one story headlined GUNMAN SPARKS SON OF SAM CHASE. Not until the penultimate paragraph did the reporter, Dunleavy, admit that the police determined that the gunman was definitely not the Son of Sam.

The following night, the killer struck for the eighth and final time. The victims, a secretary named Stacy Moskowitz and her date, Robert Violante; both were 20 years old. As the night wound down, the couple left Jasmine’s, a disco in Bay Ridge, and drove to a service road off the Belt Parkway. They got out of Violante’s Buick Skylark and walked over a footbridge leading down to the shore.

A full moon illuminated the New York Harbor, and the necklace of lights along the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge sparkled in the distance. A few minutes later the couple returned to the car. The .44-caliber killer emerged from the bushes of a nearby playground. Moskowitz was dead in a couple of days. Violante survived, but he lost one eye and most of the use of the other.

At the time, NYPD detectives were tailing their twelve best suspects, seven of whom were former cops. All of them were a safe distance from the site of the attack. What’s more, the killer had ventured into a new borough, and the victim was, for the first time, a blonde. To the Post, the leap of logic was easy. NO ONE IS SAFE FROM SON OF SAM, blared its August 1 front page. Dunleavy and Breslin both filed “exclusives” with the families of the victims. Breslin’s name had been enough to secure his interview; Dunleavy had followed the victims’ parents into the hospital at 4 A.M., donned a doctor’s smock, and posed as a bereavement counselor. “When I held their hands and hugged Jerry and Neysa Moskowitz,” he wrote, “I was stunned, shattered, and angry.” Over the next several days, the Post outdid itself, reporting, among other far-fetched things, that the Mafia had joined the hunt for the killer and serializing a suspense novel that “prefigured Son of Sam and—some believe—may actually have been read by Son of Sam.”

On August 10, the police finally apprehended the killer, David Berkowitz, in Yonkers. Murdoch’s Post ran its banner headline—CAUGHT!—in red. Inside were sixteen stories and 36 photographs, as well as the first in a series of installments from another gory crime novel “that might have inspired” the Son of Sam. The paper sold more than 1 million copies, nearly twice its average daily circulation, prompting a proud follow-up story the next day: “Kids who usually bought comic books bought the Post and tourists snapped up souvenir copies to take back home.”

In his first summer at the Post, Murdoch received one other gift from the gods—a mayoral race of historic moment. It was a crowded field, headed by the weary incumbent Abe Beame and filled out with feminist firebrand Bella Abzug, a cerebral lawyer from Queens named Mario Cuomo, and the Harlem eminence Percy Sutton. Given this competition, nobody was paying a lot of attention to another entrant in the race, Ed Koch, a journeyman reformer from Greenwich Village.

Tall and exceptionally unathletic-looking, with wide hips and narrow shoulders that looked even slimmer beneath the unflattering cut of his three-button Brooks Brothers suits, the 52-year-old Ed Koch often wore the teasing look of an uncle who was about to pull a penny from behind your ear. The writer and critic Michael Harrington described it as the expression of a “diffident, somewhat lovable schlemiel.” He had abandoned his first mayoral effort, in 1973, after just seven lonely days on the stump.

But through the tumultuous summer of ’77, Koch gained ground with a steady drumbeat of clever commercials, produced by his ruthless campaign strategist, David Garth. “Mayor Beame is asking for four more years to finish the job,” went one memorable ad. “Finish the job? Hasn’t he done enough?” Meanwhile, Koch put in eighteen-hour days, campaigning in a Winnebago blaring “N.Y.C.,” the hit song from the Broadway musical Annie.

Koch had one great advantage over his rivals. He was a pragmatist, unbeholden to New York’s liberal institutions and therefore adaptable to the changing desires of the electorate. He inveighed against the powerful unions with their stranglehold on the city budget. He championed the death penalty, which was meaningless as a practical mayoral position—the state, not the city, was in charge of punishing criminals—but it nevertheless translated into a tough-on-crime message that resonated with an increasing number of New Yorkers.

The anti-crime stance proved crucial in the wake of the blackout. Before it, Koch had been marooned in the polls in the mid-single digits, a distant fourth behind Abzug, Beame, and Cuomo. By the middle of August, with less than a month to go before the Democratic primary, Koch was at 14 percent. And he only needed to take second place. The primary rules were such that if no candidate captured 40 percent of the vote, the top two finishers would face each other in a runoff.

The break that put Koch over the top came in a phone call on the morning of August 19. The caller identified himself as Rupert.

“Rupert?” asked Koch. Then he recognized the Australian accent. “Ahhhh, Rupert.”

In a field of unreconstructed liberals, Koch stood out easily as the most conservative. He was the best Murdoch could do. The Post, Murdoch told Koch, was going to endorse him; the paper actually did much more than that, running the editorial on its front page and generating so much pro-Koch copy in the ensuing weeks that 50 Post reporters and editors signed a petition complaining about their tabloid’s biased coverage. Murdoch invited them to quit; twelve did.

What did Murdoch get in return? Some penny-ante patronage—Koch agreed to appoint a particular lawyer to a senior position in his administration—but more than that, Murdoch had wagered that Koch represented his best shot at becoming a kingmaker in his new town. It was yet another bet that paid off. Koch routed Cuomo in the runoff and went on to win the general election in November.

Like Koch, Murdoch intuitively understood the city’s desire for drama and conflict because he shared it.

Murdoch and Koch were an unlikely pair, but beneath the surface, they had a fair bit in common. They were flawed, farsighted, self-made men who intuitively understood the city’s desire for drama and conflict because they shared it. They were not idealists but egomaniacs.

To their hungry eyes, New York wasn’t a “ruined and broken city” but a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

As imposing a figure as Murdoch quickly became in New York, nobody could have foreseen the effect he would have all over the country, and indeed the world, in the coming decades. With the Post as his base, he bought up this magazine, as well as the Village Voice (later selling both), then embarked on a fearless expansion that made his company News Corp. second only to Time Warner as a U.S. media giant. His properties extend from book publishers to the latest satellites, and still plenty of newspapers (175, give or take).

The Post, though, remains the soul of the News Corp. monolith. It has never made a penny under Murdoch, but it has been a powerful cultural force. The Post’s reaction to the blackout and riots became the popular view, laying the foundation for a revised thinking about crime. The soft approaches that had been implemented with Great Society fanfare in the sixties, the focus on housing, jobs, and a supportive welfare state, lost support even among many of its early liberal champions. The Post was among the first institutions to grasp the significance of this change and to play to it. Real action on the political front took much longer to develop—crime rates continued to soar through the eighties—but by the time Rudy Giuliani took office in 1994, the city heartily embraced his zero-tolerance ideas about policing. The political support (and popular goodwill) that the NYPD enjoys to this day has its roots in those frightful events of July 1977, which the Post pinned on a weakened and disillusioned Police Department.

The Son of Sam episode, meanwhile, opened the door for a whole new brand of media gamesmanship. The hypercompetitive, interventionist tabloid tactics that were, in part, invented by the Post as it pursued the Son of Sam story spread to all corners of the media universe. Years later, when New York Times editor Howell Raines talked of “flooding the zone” in terms of how the paper covered critical events, he probably did not realize the debt he owed to its early practitioners at the New York Post. Murdoch’s editors built stories out of the thinnest shreds of news, jammed them together in unwieldy packages, and shamelessly plugged the results. And while Murdoch wasn’t the first newsman to realize news could make spectacular entertainment (see Hearst, William Randolph), he mastered the art of news hysteria, which would prove irresistable to television. That was no accident either, since Murdoch’s Fox network led the way there, too.

And with “Page Six,” and the rest of the gossip columns that were soon jockeying for space in the pages of the Post, Murdoch helped create a form of news that has since come to dominate the American media—one which invented an ever-shifting community of famous, near famous, and formerly famous people, about whom the merest personal detail could be reported as if it were a powerful revelation. Long before there was a Nick and Jessica or a Brad and Jen, Murdoch gave them a stage to dance on.

Murdoch’s Post now reconciles two contradictory impulses. It has stolen from the Daily News the mantle of New York’s populist paper, and yet it also fêtes the city’s rich and powerful, trafficking in a kind of tycoonophilia. The very same power-hungry plutocrats whom the old Post loved to torment are given the royal treatment by Murdoch’s Post—until they fall, that is, and then the Post gleefully piles on. In his free-market worldview, it’s the nastiest divorce, the scariest car chase, the grisliest murder that wins. And we cannot help but be entertained by it. We love the extremes, the sweetness of cheap victories and the agony of humiliating defeats, and he serves them up.

In Murdoch’s years as a New Yorker, a city of civil servants, political clubhouses, and labor unions became a city of real-estate developers, hedge-fund managers, and media barons. Like it or not, the New York we are living in today was born in 1977, and Murdoch was one of its founding fathers. On the ashes of the social-democratic city, he built a capitalist utopia where corporate lawyers live in the Soho lofts once occupied by garment workers; where Trump and Diller have replaced Shanker and Gotbaum as icons; where the mayor isn’t just a Republican, he’s a billionaire.