“I’ll just reiterate this for the record.”

It’s 8:42 on a Wednesday morning, and Harvey Weinstein is beginning his first monologue of the day. About ten minutes earlier, he greeted me in the lobby of the Stanhope Park Hyatt on Fifth and 81st by saying, “Let’s get a room.” He pointed to the hotel’s half-filled first-floor dining room by way of explanation. “That way, you know what I mean, we’ll be able to talk without worrying,” he said in a voice at once hurried, even-toned, and surprisingly high-pitched.

Weinstein is talking with me in a sixth-floor suite at the Stanhope because both his life and his company are very much in transition. All summer, he’d been making preparations to leave Miramax, the film company he and his brother Bob founded in 1979 and sold to to Disney for about $70 million in 1993. For the last several years, he’s been in an escalating conflict with Michael Eisner, Disney’s thin-skinned, hypercontrolling CEO, a battle characterized by vicious off-the-record sniping and occasional barely hidden salvos; this past year, that conflict has erupted onto the front pages of the Wall Street Journal and both the New York and the Los Angeles Times, as Eisner publicly questioned Miramax’s profitability and Weinstein and Eisner fought bitterly over Miramax’s right to distribute Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. Recently, Weinstein began meeting with Wall Street machers and independent financiers to discuss raising money—up to $1 billion a year—to fund a slate of movies as an independent producer. Under this scenario, Bob Weinstein would remain with Disney and continue to run Dimension Films, the hugely profitable genre division within Miramax that’s responsible for the Spy Kids, Scream, and Scary Movie franchises.

As summer stretched into fall and Bob and Harvey Weinstein plotted their futures, the rest of Miramax’s employees waited anxiously for word about their own fates. In August, the company laid off 65 employees, or about 13 percent of its workforce, an effort, according to a spokesman, to get staffing levels in line with a smaller release slate. In September, another 55 employees were canned. The mood at Miramax’s downtown headquarters was uncertain and grim as the remaining employees wondered why the Weinsteins weren’t even giving them a clue about what to expect.

The answer is, they’re not quite sure themselves. Indeed, over the summer, Harvey Weinstein’s life reached a turning point—what some might call a moment of crisis. The tough guy, infamous for putting reporters in headlocks and for public screaming fits, had become oddly vulnerable. He was thinking about what he would do for the rest of his life. Had Miramax run its course?

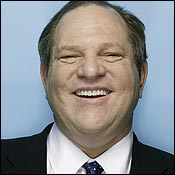

On this Wednesday morning, a healthy dusting of gray and brown stubble covers the lower half of Harvey Weinstein’s fleshy face. He’s been living in lower Manhattan as of late; Weinstein and his wife, Eve—who began work as his assistant in 1986—separated earlier this year.

Weinstein has with him a duffel bag and a metal briefcase he’s used since his days as a rock promoter in the seventies. HALLIBURTON is stamped on the top of the briefcase, near the handle—“It reminds me of this corrupt fucking administration, you know what I mean?” he says. He’s wearing a white dress shirt. A pair of black suspenders holds up his slacks, which these days have a little extra room around the waist. We’re sitting at a smallish table in a sixth-floor suite, Weinstein on one side, me on the other. Matthew Hiltzik, Weinstein’s quick-talking and long-suffering spokesman, and Emily Feingold, one of his four full-time New York–based assistants, get comfortable in easy chairs.

“The Fahrenheit 9/11 deal not getting done had only to do with trying to screw Bob and Harvey,” said a lawyer. “It’s bizarre.”

It takes Weinstein several minutes to settle in. First he sits down. Then he gets up to take off his blazer. Then he sits down again, but not before taking two soft packs of Vantage cigarettes out of his pocket and throwing them down on the table. He pulls out a cigarette and places it down on the table, too. He gets up, walks over to the bathroom, gets a glass, fills it with water, sits down, lights his cigarette, flicks some ash into the water, and starts to speak. I’ve barely said a word. The interview has begun.

But this morning’s most pressing topic isn’t Michael Eisner, or Miramax’s legacy, or even Weinstein’s own future. What Harvey Weinstein is so eager to get on the record—what he waits for me to turn on my tape recorder for—is his theory about the correlation between his blood-glucose levels and his infamous temper tantrums.

“You know, for years I used to read about myself. They’d say, ‘He has a temper’ or ‘He’s a bully’ or something like that, and it always bothered me,” Weinstein tells me. “You know, I always felt guilty about it. Somebody said, ‘The flower bill that is written by Harvey could have’—you know what I mean—‘because he needs so many apologies, could fund a small nation.’

“And, you know, Meryl Poster, my head of production and also a dear friend, sent me to anger-management specialists. Of course, they always ask me about my mother, Miriam. And the trick about Miriam is, my brother and I love her. She was widowed maybe 30, 40 years ago, so we grew up, you know, with Mom. She was incredibly supportive and tough on the both of us. She’s still, you know, the one person you, we have to toe the line with, you know.

“But I found out, and I just share this with everybody, is that the relationship to sugar in my body … There’s a … where my thing went from 50 to 250.

“What happened was, I was never an eater of breakfast or anything. In the morning, I used to just have a cup of coffee in the morning, went out to work, and then forget breakfast, sometimes lunch, and then make up for it with an overturned packet of plain M&M’s in my suit coat. And I would just eat M&M’s all day, sweets, you know, for what I thought was energy, which is not energy at all, now that I’m off of it. And what happened was the glucose level would go from 50 to 250 in my case. It’s not in everybody’s case. Some people handle sweets better.

“And I would hit the adrenaline. So that’s what caused these outbursts, you know. We had to find out through a specialized doctor. I had to go to a doctor. We found out I have adult-onset diabetes too as a result of this, so in the last year, I’ve lost 60 pounds eating a low-carbohydrate diet, you know, and exercise, and, um, in the last two, three years, as soon as I started to recognize the sugar thing, there have been no outbursts. There’s been no anything at all. Zero. There’s been nothing. Not a word to anybody.”

There’s a knock at the door: Breakfast has arrived. The Stanhope is out of soy milk, so Weinstein makes do with a splash of low-fat milk in his coffee. He extinguishes his cigarette in the water glass and then mutters to himself, “That’s disgusting.” His meal—an omelette—comes with a side of home fries, which he shovels onto a small plate and puts over by the television.

When talking with Weinstein, it’s important to remember that he’s both an expert showman and an inveterate story whore. He gets off on good narrative and becomes frustrated when the pieces don’t fit together the way they should. It’s part of what makes him such a successful studio executive. It also means that in real life, away from the celluloid screen, he’s not likely to let the messy realities of the world get in the way of a good anecdote. For instance: Max Weinstein died 28 years ago, when Bob and Harvey both were well into their twenties and no longer living at home. The Weinsteins didn’t “grow up, you know, with Mom.”

When it comes to Miramax’s legacy and the company’s relationship to Disney, Weinstein doesn’t feel the need to exaggerate; indeed, because of a clause in his contract that forbids him from discussing the company, he prefers to let others make his case for him. And despite Weinstein’s well-deserved reputation for being an ogre, for running roughshod over anyone who gets in his way, that case is pretty convincing. As more than one person has told me, Michael Eisner could be the one person in all of Hollywood who makes Harvey Weinstein seem sympathetic and likable.

“You know what I mean?”

Here’s the CliffsNotes version of the squabble between Weinstein and Eisner:

Harvey thinks Michael is a soulless, tasteless, lying prick.

Michael thinks Harvey is a profligate boor and a bully.

Weinstein has long found it hard to believe that Eisner, who can present as the bumbling savant responsible for Happy Days, was actually his boss. Eisner, in turn, hated having to put up with the scorn of the Queens-raised, coarse-mouthed Weinstein. But the two found a way to work together, because their relationship was so mutually profitable.

In the past few years, however, Eisner became convinced that Weinstein was more interested in making tent-pole movies, $70 million, $80 million, even $100 million features with high risk and comparatively low reward. There was Gangs of New York, Martin Scorsese’s 2002 epic. There was Cold Mountain, Anthony Minghella’s 2003 disappointment. As one studio exec put it, “When the cat shit gets bigger than the cat, time to get rid of the cat.”

“When we did the original Miramax deal, they had a formula that was very appealing,” says one movie executive. “Do these $10 million movies, and maybe on some you lost a little, and on some you made a whole lot. The Weinsteins became emboldened by their success. They had become a major studio disguised as an independent film company.”

A former Miramax exec puts a finer point on it: “Harvey Weinstein became like a drug addict trying to support his habit. In the end, he went native. He wanted to be another big player in Hollywood. He used to be a real outsider. And now he and Bob want to be let into the club.”

Even Harvey himself says he understands why Disney would want him to keep costs down. “I’ve had such a great track record in making a huge profit when the movies are smaller,” he says, gesturing animatedly in front of his couch in his Tribeca office. “But I also, you know, you want to grow with my artists. If Martin Scorsese wants to paint a canvas like Gangs of New York or Aviator, so be it. In five years, Gangs of New York will be totally profitable, if not sooner.”

A more important factor in the current standoff is probably Eisner’s personal dislike of the brothers. “Nobody at Disney ever gave these guys a chance,” says one former Disney executive. “The old studio system viewed them as pigs. It was more of a respect thing than anything else.”

As the nineties progressed, the company lost the various Disney executives that the Weinsteins had been able to work with: Disney president Frank Wells, who served as a lubricant between the Weinsteins and Eisner, died in a helicopter crash in 1994. That same year, Jeffrey Katzenberg, the man who brokered the initial deal between Miramax and Disney, left Disney after his own bitter dispute with Eisner. “When we made the deal, it was with Jeffrey, Frank Wells, and Michael Eisner,” Weinstein told me one morning in his office. “Bob and I never could have predicted that Frank would die and Jeffrey leave. We honest-to-God thought, Okay, here it is: Miramax will always be part of this company. I thought it would be a forever situation. And we still hope it can be.”

Weinstein—who, if you really press him, will admit he’s not an easy guy to work with—never exactly worked to fit into Disney’s culture. He’d snub Eisner in Oscar season, and he’s never been shy about either his opinions or his healthy sense of his own worth. Lately, after a decade or so as one of the most successful studio heads in the business, he began to yearn for a true empire of his own, the type where he didn’t need to worry about the stiffs in Burbank. He didn’t like thinking of himself as an employee, but every now and then Eisner made sure to remind him of his place. Weinstein began to be told he wasn’t allowed to smoke when he visited Disney’s Burbank headquarters. His astronomical expenses were questioned, with Disney sending increasingly belittling memos about the costs of hotel bills or airfare. (“When you’re talking about a creative process, and the potential profits from these kinds of enterprises, it makes no sense to argue with these guys about hotel rooms,” says Steve Rattner, a Weinstein friend.)

“Harvey was treated a bit like the dumb uncle in the attack,” says someone who knows both Eisner and Weinstein. “He’s been squeezed mercilessly. For what? Every single other one of [Disney’s] divisions, with the exception of ESPN, is doing horribly. Look at Hidalgo. Look at Home on the Range: $100 million flops. And they’re on Harvey about Gangs of New York or Cold Mountain?”

When came the epic dustup over Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. On May 12, 2003, a Disney executive sent Harvey Wein-stein a letter saying, “You cannot release this movie.” Four days later, another letter was sent. This one outlined why Miramax would not be allowed to release the film—it was a “restrictive picture” under the Miramax-Disney contract, it was politically partisan, etc.—and instructed Miramax to divest itself of its interest in the project.

Weinstein, all sides agree, went ahead and funded the movie anyway. And, according to Disney, Weinstein hid the $6 million budget in other projects. In this version, Eisner found out about Miramax’s continued involvement only when Weinstein casually mentioned that he’d like his boss to take a look at the film as the two men were strolling toward an elevator bank in Disney’s California headquarters.

The problem is, it’s not true. Costs associated with the movie weren’t hidden; indeed, quarterly budget reports sent from Miramax to Disney in 2003 include a line item for “FAHRENHEIT 911” complete with a film code (“M1621”), a date of first cost (“FY03 Q3”), and a tentative release date (“Oct-04”). Moore even said publicly the checks came from Burbank. (Disney never produced for me the reports where Fahrenheit 9/11 supposedly should have appeared but didn’t; a spokeswoman told me I was “naïve” and “in the tank” when I explained I’d need to see the reports myself.)

This level of acrimony is not all that rare when it comes to Miramax and Disney. But in May 2004, the dispute became glaringly, embarrassingly public. Disney, the New York Times reported, would under no circumstances permit Miramax to distribute the movie. Michael Moore, seeing a chance to gin up some free and sympathetic publicity, cried censorship. Moore’s agent, Ari Emanuel, told the Times that Eisner had told him he didn’t want to endanger tax breaks Disney gets in Florida, where Jeb Bush is governor. (In another rhetorical sleight of hand, a Disney spokeswoman pointed to Emanuel’s comment as proof that Weinstein knew he was not “allowed” to fund Moore’s movie—while at the same time claiming Emanuel was lying about Eisner’s statement concerning Disney’s Florida tax breaks.)

It shouldn’t be a surprise that Eisner, who isn’t particularly skilled at the public-relations game (see Katzenberg, Jeffrey, lawsuit with. See also Ovitz, Michael, compensation of), lost this round handily. Fahrenheit 9/11 won the Palme d’Or at Cannes; Disney sold the movie to the Weinsteins but told them Miramax wasn’t allowed to have anything to do with its distribution; the Weinsteins cut a deal with Lions Gate; and Moore’s $6 million movie went on to gross more than $100 million domestically.

“I have never seen the level of emotion that exists at the Disney Company,” says a lawyer who was involved in the negotiations. “It’s a huge public company that makes its decisions based on emotion. It’s bizarre. The Fahrenheit 9/11 deal not getting done had only to do with trying to screw Bob and Harvey.”

Curiously, as part of the complex agreement that was eventually brokered, the Weinsteins were not allowed to make any more money off the movie than they would have had Miramax distributed the movie on its own. Disney, after huffily insisting it wanted nothing to do with the project, would get the rest—although it also said that money would be donated to charity. (As of the last week in September, Disney had not designated a charity to receive its share of the windfall. When will that happen? “When it’s appropriate,” said a Disney spokeswoman. When will it be appropriate? “When we deem it’s appropriate. This is a ridiculous question.” Will the interest on the money also be donated to charity? “Are you serious? I can’t believe this. Are you serious?”)

By July, things had gotten so bad that Harvey Weinstein was telling anyone who’d listen that he’d likely be gone by the end of Oscar season, if not before. He thought the future would look something like this: Bob Weinstein would stay at Dimension Films. He’d get somewhere between $300 million and $350 million a year to work with. Disney executives, meanwhile, began telling reporters sotto voce that they heard that even Bob Weinstein was sick of Harvey, that Bob was pissed that he was the one who made all the money but got none of the credit, something Bob Weinstein vocally denies.

What, exactly, Harvey was planning on doing was unclear. He’s proud—immensely proud—of Miramax’s library, which includes movies like Pulp Fiction, The English Patient, Shakespeare in Love, and Chicago. It physically pained him to think about leaving it behind. (Since Miramax had been bought outright by Disney, it would retain the rights to all of Miramax’s back catalogue.) And he had begun to realize that, at age 52—the same age his father, Max, died of a heart attack—he didn’t want to spend the rest of his career fighting against executives he had a hard time respecting.

So Weinstein began to consider his options. Perhaps he’d start an independent production company. Perhaps something more nebulous: an umbrella concern designed to fund Weinstein’s interest in theater (he’d helped fund The Producers), literature (Miramax’s book division is the one profitable outshoot of the Talk-magazine debacle), sports (Weinstein is a hard-core Yankees fan and has speculated idly about one day buying the Mets), and politics.

But just when the future seemed all but written—just when Harvey was saying it seemed likely he’d leave the company, maybe even by the end of September—Disney insulted Bob Weinstein. The deal Disney put on the table for Bob, according to sources close to the Weinsteins, was so paltry—he stood to make less than half of what he is currently making, maybe as little as a quarter, and was offered virtually no back-end participation—that by the time Labor Day rolled around, the Weinstein brothers decided to stick together and fight it out.

“We’d like to continue,” says Bob Weinstein in between bites of a small Caesar salad he’s eating in a back room of the Tribeca Grill, which sits on the ground floor of the building that houses Miramax’s offices. While Harvey Weinstein relishes the spotlight and travels around the world to film festivals, Bob Weinstein prefers to stay in the background, nesting in New York. People who know the Weinsteins agree that the two men seem more united than they have been in years.

“We are brothers. We’re partners,” says Bob Weinstein. “We’re not separating in any fashion. It was never a separation, by the way. It was only a reconfiguration—we were willing to say okay in this byzantine kind of setup. It was never a situation where if I made $10 and Harvey made a dollar we were splitting down the middle no matter what. It was never like, ‘Oh, Bob’s running Dimension and Harvey’s running Miramax.’

“I’m proud of my brother. He has changed a lot of the rough edges, and people have noticed it. People in the press, maybe they want the old Harvey. They’re going, ‘What’s with the kinder, gentler Harvey?’ But Harvey actually took a little self-examination and said, ‘I could probably get the same things done and be less, uh, strict.’ ”

By September 10, when Michael Eisner announced he would step down as Disney’s CEO when his contract expires in 2006, the Weinsteins, whose own contracts with Disney run out next year, had decided on a course of action. Having all but given up on working out an acceptable deal with Eisner, the Weinsteins are now hoping Disney’s board of directors will step in and force Eisner to make a deal for one of Disney’s most successful units. After all, as virtually everyone associated with Miramax is fond of pointing out, Miramax has, most years, handily beaten Touchstone, Disney’s own live-action studio, both commercially and critically. Touchstone is currently promoting the disappointing Mr. 3000 and the dead-on-arrival The Last Shot, a movie the Times said was made “for no good reason at all.” Miramax will open the highly anticipated Finding Neverland in November, which stars Johnny Depp as J. M. Barrie, the creator of Peter Pan. Come Oscar time, Neverland will likely compete with Miramax’s Aviator, Martin Scorsese’s biopic of Howard Hughes, with Leonardo DiCaprio in the lead role.

Michael Eisner insists that Miramax’s past successes count for little; indeed, he says that the division hasn’t even been profitable for three of the past five years. And he’s been telling friends and associates he has no desire to deal with the Weinsteins anymore.

“I would predict that they will have to find their home someplace else,” says Bert Fields, the Hollywood lawyer who, along with David Boies, is working with the Weinsteins in their contract negotiations. “My own feeling is, in his heart of hearts, Michael Eisner has no intention of making a deal with the Weinsteins. In my personal opinion, for years he’s followed a program based on personal animus. And he’s going to fight against the conclusion of any type of deal.”

If that’s true, Disney could lose out on the services of a number of high-profile stars. “Those two dudes, they built their company from scratch, man,” says Kevin Smith, who signed a contract with Miramax after his 1994 hit Clerks. “I for one am glad they’re digging in and staying—that just means the world to me. Those dudes have been my role models. They’re very serious about what they do. Of course, it’s business, so they like to earn a buck. But they’re dedicated to forwarding American film and cinema.

“Without Harvey and Bob, there’s no Pulp Fiction. Quentin is still working in a video store. Truly Madly Deeply is Anthony Minghella’s best-known film. And Robert Rodriguez is stuck making mariachi flicks at Columbia.”

Back in 2002, when Disney began to grumble about Miramax’s bigger-budget projects, the Weinsteins approached Wall Street financiers and investment banks and inquired about setting up an alternate line of funding. Goldman Sachs offered the Weinsteins $500 million in capital, enough money to help fund a three-year slate of films. The debt was so cheap, according to a Goldman banker, it would have been cheaper than Disney’s own cost of capital. But Disney wouldn’t let them do it.

“If Harvey left Disney tomorrow and he wanted to raise a billion dollars in equity, me and every other banker on Wall Street would jump to do it,” says a Goldman executive. “If you look at all of the historical returns of all of the major studios over the past seven years, Miramax is in the top two.”

That, at least according to Bert Fields, isn’t going to matter. “In my opinion, Michael Eisner has followed a policy of vindictive, punitive actions toward Bob and Harvey. He has created this terrible feeling of rancor and bitterness.” So, will Bob and Harvey end up elsewhere? “I would think they’d consider all their options,” Fields says. “They could raise a sizable amount of money on their own, but look: Time Warner would work very nicely. They could fit in very nicely at the corporate culture at Fox. Murdoch’s a guy who appreciates profit. So’s Dick Parsons. They could fit in at the new, expanded Sony.”

That, says Fields, wouldn’t be the Weinsteins’ first choice. “For some time, the Weinsteins have been pressing to bring their position before the board. They offered to buy Miramax back at any reasonable price and pleaded with Eisner to bring that to the board. So far as we know, that never happened.” Indeed, Eisner has told friends that if Miramax were valued at $2 billion, he wouldn’t sell it back to the Weinsteins for anything less than $3 billion.

Even if the Weinsteins end up leaving the company whose name is a blending of Miriam and Max, the Weinsteins’ parents, they likely won’t be short on options. “We know this company well,” says Pete Petersen, the chairman and co-founder of the Blackstone Group. “There’s no question in my mind they can finance a new business if that’s what they decide to do.”

Eisner, meanwhile, has to be thinking about his own mixed legacy. He unquestionably rescued the moribund Disney after taking it over in 1984—at the time, Disney’s market cap was $2.8 billion. Today it’s $58.4 billion. But for the past decade, Disney’s stock has often struggled. Attendance at the company’s theme parks is down, ABC is so mired in third place that it has seemingly found a permanent identity as the worst-performing network. This past March, Disney stripped Eisner of his chairmanship after 45 percent of shareholders delivered a stunning vote of no-confidence.

Back at the Stanhope, Weinstein is finishing up breakfast. He’s obviously pleased with the changes he says he’s been able to make in his behavior. Indeed, as he’s fond of pointing out, it’s been over two years since his last public explosion, a March 4, 2002, incident that was recounted in Peter Biskind’s book Down and Dirty Pictures. The occasion was a test screening of Julie Taymor’s film Frida at the Lincoln Square Theater at 68th and Broadway. The film tested well. Standing in the lobby after the audience had filed out, Weinstein asked Taymor what she thought of the audience’s response. “They enjoyed the movie,” Taymor said. “The film succeeded.”

This, apparently, was not the response Weinstein was looking for. “You are the most arrogant person I have ever met!” Weinstein screamed, spittle flying out of his mouth. “Go market the fucking film yourself!” Weinstein turned to Taymor’s agent, Bart Walker, and told him to “get the fuck out of here.” He then turned to Taymor’s companion, Elliott Goldenthal. “I don’t like the look on your face. Why don’t you defend your wife, so I can beat the shit out of you.” Finally, he turned to a group of Miramax executives and picked them off, one by one. “You’re fired. You’re fired. You’re fired. You’re fired.”

Incidents like that, Weinstein insists, are all in the past, simply the result of spiked glucose levels and poor nutrition.

“Now I’ll look at the movie and say, ‘This is boring,’ and instead of saying ‘You asshole, fix it,’ I would say, ‘All right, guys, this is boring. How are we going to fix it? How should we do this? Do you guys realize this is not moving the way it should?’ or ‘It doesn’t have the power of the scene’ or ‘That’s the wrong actor in a casting session.’

“And I find that I’ve been able to make the same points, but I just say it in a calmer way because I feel calmer. In other words, I don’t have that anger button. It doesn’t hit me. So I think so much of anger management might fortunately be related to one’s physical diet, and I began to preach it, which is odd for me, because I don’t preach anything except getting rid of George Bush, you know, which is my mantra.

“All that self-control stuff, I tried all that stuff from analysts. I went everywhere to these guys, every kind of anger-management, psychologist, psychiatrist. ‘Get rid of my temper, get rid of my temper.’ And there was only one guy who just said, ‘I don’t think this is related to, uh, issues. I think there has got to be something wrong.’

“My pop used to always take us—my dad would say, ‘All right guys, we had a tough day today’—we were only 10 years old—‘let’s go to the pizza place,’ because my dad was overweight, so we would read magazines and eat pizza at Angelo’s Pizza on Main Street, so that was the reward. Or we would go and have a chocolate egg cream with that, so it was always sweets-related. ’Cause Dad was overweight, and my relationship with sugar has been the worst relationship of my life, but now I’ve tamed it.

“Here’s the other thing, and it has never been said by me,” Weinstein says. “And I will go on the record with this.

“When Bob and I started Miramax, the idea that we always had was, first, it’s all about the love of movies, and taking the risk to do a good movie that no one would think possible is to bring quality to the industry. But on a business level, what I always said was, we will build Disney an asset. You almost have to compare Miramax to a real-estate company. You buy buildings; you don’t get the money back on the buildings right away. But pretty soon you turn around and you have 100 buildings and that’s what building a 660-some library is.”

Weinstein looked at his watch, signaled to Emily Feingold, and popped up out of his chair. “We have to go.” As he gathers up his stuff, Weinstein talked eagerly about Aviator, which he would screen that night for a handful of Miramax executives. He opens the door and turns to face Hiltzik.

“You working on those fucking Kerry spots? I want to see those spots.” Hiltzik, who took time off from Miramax to work for Hillary Clinton’s Senate campaign, has been doing some volunteer work for Kerry. He explains to Weinstein that he’s almost done.

For an instant, the old Harvey seems about to burst in. “You have time to read that fucking Joe Namath book but you don’t have time to do this?” Weinstein says to Hiltzik, an edge in his voice. “This is your country. This is the future of your country we’re talking about, you know?”

It’s a habit, a performance he’s done many times. But change is possible. Weinstein turns, looks at me, and stops.

“Let’s just do it. Okay? Okay. Good-bye.”