Four months away from the Republican National Convention at Madison Square Garden, activists are circling their welcome wagons, predicting “a battle for ground zero,” a “Burning Man festival for the city,” “a political disaster,” “a disciplined, organized protest,” “a culture war”—five days that are “part blackout, part Woodstock,” “worse than Miami,” “better than Seattle,” “our Chicago ’68.” Will these five days help push Bush out of office or spark a red-state backlash that cements his reelection? Either way, says 26-year-old activist Brandon Neubauer, “it’s already sort of legendary.”

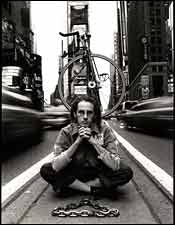

Neubauer, an environmentalist whose wiry bicyclist’s frame is capped by a spider fern of blond dreadlocks, is one of more than 100 activists packed into the St. Marks Church meeting hall. Calling the meeting to order is Brooke Lehman, all five-foot-three of her, in a burgundy velour hoodie and blue jeans. A co-owner of the radical Lower East Side bookstore Bluestockings, Lehman, 32, is also a founder of the Direct Action Network (DAN), which organized many of the 1999 Seattle World Trade Organization protests. She explains that she’ll be conducting business in the specialized style that dan pushes to minimize infighting—a kind of Robert’s Rules of Order for today’s anarcho-bureaucratic protester. It’s so complex that Lehman needs a board full of bulleted points and four color-coded handouts to explain it.

Tonight, like most other No RNC Clearinghouse nights, Lehman’s the “not-in-charge person” (according to the yellow handout), who will be facilitating the nonhierarchical “consensus decision making” (blue handout) of an assembly that is not an organization, a group, or even a body. “This is only a tool and not an entity,” she clarifies. “Let’s do introductions.”

With the curt professionalism of a boardroom veteran, Lehman jabs her finger toward guests in a quick roll call, revealing only attendees’ first names (because the cops might be watching) and group affiliations (like NYC AIDS Housing Network). Curious first-timers pepper this monthly meeting, but so do many of the all-stars of the Seattle, Genoa, and Miami trade protests, as well as veterans of Vietnam War rallies, City Hall stand-downs, and marches on Washington.

At the back of the room, William K. Dobbs, who participated in ACT UP’s Day of Desperation in 1991, sits next to the disheveled Steve Ault, who co-chaired the first gay-and-lesbian march on Washington in 1979. At the front, Jamie Moran, the skeptical co-founder of the obsessive Website RNCNotWelcome.org, sits near the direct-action specialist Lisa Fithian and Tim Doody, a hyper Ruckus Society alum who just returned from spraying graffiti on the new Israeli wall in the West Bank.

Lehman says it’s time for reports from “affinity groups” (white handout)—small groups of like-minded activists working toward specific goals—and spokespeople scramble to the front. “Two minutes each,” Lehman directs.

What follows is a rapid-fire update on the state of No RNC actions: The Structure group is working on a “Life After Capitalism” conference with academic stars like No Logo author Naomi Klein; Jeff from the Legal group begs for more volunteers; Alex from Arts asks people to locate “street-facing windows for signage”; Hubert from Housing reports accommodations requests for large out-of-town groups; Tim from Trainings advertises a “direct-action salon series”; Deanna lets people know the Bowery Poetry Club “will be open 24 hours during the RNC, as a safe haven from Republicans”; Jonny America announces a “revel-utionary” agenda of “flash mobs” (instant gatherings coordinated by e-mail and instant messages) as well as a ceremonial “Declaration of Independence from George II.”

Others advertise rallies, concerts, the free printing of 10,000 anti-Bush stickers—and many more meetings. When Neubauer steps forward to explain that his bicyclist-environmentalist organization Time’s UP! will hold a “Bike National Convention” the week before the RNC, people begin wiggling their fingers in the air, in some once-removed secret handshake.

Perplexed, a few first-timers giggle.

“We do this instead of clapping, to keep things moving,” Lehman explains, wiggling her fingers skyward in the sign language activists describe as “twinkling.” (Later, some express displeasure by forming a diamond with their fingers in front of their faces, like extras in a Prince video.) Then she speeds things along: “Sorry, your time’s up,” she advises. “That’s on the agenda for later.”

When Lehman tees up a discussion about media access (white handout No. 2), attendees express concern that recordings might be used against them—and wonder whether cops have already infiltrated. (Perhaps with good reason: In February, Massachusetts police reportedly discovered that two NYPD officers had attended a meeting of Boston’s Black Tea Society protest group.) To organize the tense debate, Lehman calls for “stacks” (manageable groups consisting of five comments each) by assigning each raised hand a number, like a deli butcher. Then she calls on speakers by digit—“One!” (Cameras are fine.) “Two!” (I don’t want to be photographed.) “Three!” (I don’t care either way.)—repeating, as necessary, until the matter is settled.

This strict anarchist process is a strange commingling of New Age jargon (the white handout describes a role called “vibes watcher”) and businesslike administration (using the master’s tools to dismantle his house). But if the packed room is any guide, it seems to be an effective way to get strong-minded activists working together.

Also in this issue

How to Care for an Angry Mob

Ray Kelly and the NYPD have bigger things to worry about than, say, a few hundred thousand protesters. (May 17, 2004)Previously

The Conventioneer

The Republican National Convention comes to town in just nine months. Meet Bill Harris, the Alabama conservative, Civil War buff, and dove hunter in charge. (December 8, 2003)

“Tell me what democracy looks like!” marchers love to shout, usually at the police. Well, this is what democracy looks like, in an orange-alert age: A “consensus” meeting; an “affinity group”; a permit; a legal observer; a bike; a direct-action salon; a tent-city; a flash mob; a Website. Twinkling.

Forget about that great gettin’-up morning when the People spontaneously rise to Power—it never happens like that, anyway. Protest has been professionalized; these are the tools. And though the Republican convention is still months away, activists have long been evaluating which tools (out of the 198 listed on the green handout, and then some) will help them steal the thunder of the most expensive political convention in history—a $91 million event, held in New York City for the first time and closer to the election than ever. A wartime spectacle produced by the same Hollywood set designer who brought you the Doha press center, and defended by 10,000 NYPD officers.

Now here’s the problem: Political conventions have been boring, predictable coronations for decades, and the protests outside have devolved into spectacles just as dull. Even this year, there aren’t any serious calls to shut down the convention, because activists understand there’s no genuine process to interrupt or influence; the Republicans are here for a glorified pep rally.

So why, then, since as early as last summer, have activists been working so hard on preparation? “Coming to New York to have a convention this late is just so in-your-face,” says Neubauer, alluding to September 11. “People take it personally.”

But as disgusted as he is at everything from Bush’s environmental policies to the war in Iraq, Neubauer, bright-eyed and smiling, doesn’t sound mad—in fact, he’s pumped. “The general vibe in America is that being out in the streets is something that happened in the sixties—that now it’s just people who have tattoos and dreadlocks and piercings,” says Neubauer, whose own dreads are pulled back neatly. “But this amazing community has been alive and serious for a long time now. Maybe that story will be told, probably ten or twenty years from now, when everyone’s legendary heroes.”

The anti-Bush nation preparing to overwhelm the convention is not of one mind (they’re leftists, after all). Most are angrily optimistic. Some worry that protests will be too obedient; others that the television cameras will focus on the freaks who will make red-state viewers sneer. And beyond the organized, there is the specter of the disorganized—those who might harbor more violent ambitions and would never deign to visit a meeting like this. Even among orderly activists, there remains the possibility that nasty exchanges with the NYPD or pro-Bush agitators could incite and divide the crowd, panicking some and endangering everyone. There is no way to predict what will happen when hundreds of thousands of riled-up protesters come face-to-face with riot cops.

But for now and in this room, the protesters share a decidedly sunny goal. They want to demonstrate to America that their liberal, diverse, urbane, never-sleeping, sometime-bohemian, Wall-Street-and-new-Times-Square-notwithstanding city is definitely not Bush country. And on these grounds, they will almost certainly succeed. Whether that symbolic victory will accomplish anything—change a voter’s mind or, dare they even say it, tip the election to the Democrats—well, that’s another matter entirely.

Like Che Guevara t-shirts, mass demonstrations—the most traditional tactic in the radical repertoire—are back in style, despite Bush’s shrugging them off as “focus groups.” Organizers of the recent abortion-rights march on Washington claim they gathered 1.15 million people for the largest march in American history. There’s still no better way for activist groups to demonstrate the depth and scope of popular objection—so there will be massive rallies and marches at the RNC.

Numbers could be huge, partly because signing up for the revolution has never been easier: Busing is planned from Washington, Chicago, and elsewhere, and Websites abound with links to day care, housing, pet-sitting, vegan restaurants, and more; every vegetarian single mother from Houston with a pet iguana will be able to shout down Bush without worries. Some RNC delegates may not be so well accommodated.

NARAL and at least nineteen other organizations, including the Central Labor Council, MoveOn.org, the Green Party, and the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, have filed RNC-protest-permit applications—Russell Simmons has even promised “the biggest hip-hop gathering ever” to protest the Rockefeller drug laws. But the most anticipated demonstration, scheduled the day before the convention, is being planned by United for Peace and Justice, the group that co-organized the city’s last two major antiwar protests.

“We’re not going to talk numbers, because we don’t want to overpromise,” UFPJ’s Leslie Cagan says carefully, though her permit application allows for 250,000. Dressed casually and wearing New Balance sneakers engineered specifically for marathon runners and lifelong marchers, Cagan sips a Coke in her dismal fifth-floor-walk-up office. As national coordinator of a two-year-old umbrella group formed in opposition to the Iraq war, she coordinates actions for more than 800 groups with a staff of five and a paltry budget. From the tiny Young Koreans United of Chicago to the Green Party and the Communist Party USA, all have largely set aside the crabs-in-a-barrel infighting common to the left (except for the ever-divisive and belligerent group answer, which derides all American presidents equally and supports almost any military opponent of the United States). As Cagan puts it: “We don’t have to sit around wondering, Is there some part of his tax program that we agree with?”

“It’s true,” says UFPJ’s lanky, droll spokesman, William K. Dobbs, who leans back in a beat-up office chair in front of a bush lies who dies? poster. “It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen—everyone’s been talking tactics for nearly a year.”

UFPJ’s been organizing its march since last June. “We just want to set the tone—and make it very clear that the empire-building agenda of the Bush administration has got to be stopped,” explains Cagan, a Bronx native whose clipped hair has turned steel gray after more than 40 years of fighting the Man. “That is, if we ever get our permits.”

“Oh, the old days of just going out on the street and having a great, punchy protest are over,” Dobbs moans, playing the crusty radical—and he’s right. Today’s mass demonstration requires a back-end battalion of support that only a large group like UFPJ can coordinate: legal observers, lawyers, security personnel, free-speech experts from the NYCLU and the Center for Constitutional Rights, documentarians on the lookout for police brutality, permit-process experts—the list goes on.

“Well, I know how to get a permit,” Cagan adds flatly, if not quite proudly. “I know how to deal with the police … I know how to rent the Porta Pottis. That stuff, I can do.”

Yet, after three meetings at police headquarters, Cagan has come away empty-handed. Her proposed march would move within what First Amendment lawyers call “sight and sound” of Madison Square Garden, proceeding uptown past the Garden on Eighth Avenue to Central Park West. But the NYPD has counteroffered a loop that would allow “sight and sound” a full block away from the Garden, before circling back down Eleventh Avenue—a far cry from photogenic Central Park.

“Eleventh Avenue!” Cagan cries, convinced that few New Yorkers could even see the protest there. “At the first meeting, one person even said, ‘What about out in Queens?’ ”

There is some internal pressure on Cagan. Not everyone in the activist world was happy about her previous marches, which were thought to be too compliant to the wishes of the police. People will be watching how much better she can do this time.

If the RNC were booked for Anchorage, you could predict Alaskan liberals to throw snowballs at Republicans; here, in media-crazy Manhattan, New York’s full array of countercultural micro-celebrities, musicians, and pranksters will throw street parties, arts festivals, poetry slams, and comedy and fashion shows—a telegenic twist on the “Festival of Life” Abbie Hoffman proposed for Chicago in 1968 (the Yippies have even proposed their own geriatric jamboree in Tompkins Square Park).

“There’s a whole gallery of Republican characters coming here to make their theater with 9/11, to use a kind of conquered New York as the backdrop,” says Bill Talen, a patron saint of downtown theater who slips easily into the evangelical cadence of his alter ego, the Reverend Billy. “We have to match that theater, to supplant it, and the RNC is going to be our Ninth Symphony.”

“I want the RNC to be like spring break,” says one activist. “You’ll see me on Hannity & Colmes.”

Talen, a zealous performer with an Elvis-like pompadour, is among those who are frustrated with Cagan’s UFPJ marches. “It was practically collegial—like us and the police were checking in with each other!” he says. “I mean, I like UFPJ. But if I’m going out to protest, I don’t want to get penned in by some sky-blue sawhorses and a bunch of policemen.”

Talen has been been busy organizing weekly “First Amendment Out Loud” sessions with his “Church of Stop Shopping” vol-unteers who mysteriously assemble in the World Trade Center path station every Tuesday to recite the First Amendment into their cell phones. The young group Greene Dragon—named after the pub where John Hancock and Paul Revere used to drink—promises a Paul Revere’s ride, for which the group’s impresario, Jonny America, will suit up in Colonial garb and charge down Lexington Avenue on horseback, shouting, “The Republicans are coming! The Republicans are coming!” And Parsons M.F.A. student Joshua Kinberg is launching a Girls Gone Wild–inspired Boobs Against Bush Website, which will collect photos of women with messages LIKE MORE CLEAVAGE, LESS TAX CUTS on their breasts. “I want the RNC to be like spring break,” he says. “You’ll see me on Hannity & Colmes.”

While The Daily Show and Al Franken have successfully mixed critique with comedy, a debate’s brewing about whether many of these “absurd responses to an absurd war” actions will do more harm than good. Local activist Ben Shepard, editor of the anthology From act up to the WTO, recently published a call for a “post-camp activist moment”: “If we are going to suggest that another world is possible,” he wrote, “we’d better be able to suggest that this world is more than simply ridiculous.” It’s not hard to imagine that flag-waving Republicans will look high-minded compared with, say, the Missile Dick Chicks, who wear leotards and tin-foil phalluses and sing songs like “Shop! in the Name of War.”

Protesters fully expect the “corporate media” they distrust will reduce their politics to the kind of stereotypical images the conservative Freepers (the influential bloggers at freerepublic.com) are salivating over. “The GOP convention will bring national attention to the sharp contrast between GOP seriousness and Democrat virulence,” writes one Freeper hopefully. “The images of topless lesbian answer communists railing against capitalism and rioting outside the staid GOP convention will seal the doom of whoever gets the Dem nomination.”

To provide ballast, other local activists are planning serious, targeted protests, including “reality tours” of poor outer-borough neighborhoods, environmental protests related to ground zero, and events involving September 11 families, clergy, and veterans. Some are developing sophisticated media campaigns that capitalize on New York’s peculiar natural resources. Kevin Slavin, a vice-president at a downtown ad agency, who only half-ironically wears a NASCAR jacket slathered in corporate logos, has designed his first protest campaign, called Signal Orange. It utilizes skills he honed working on ads for military products like the F-22 fighter-bomber.

“I’ve picked the one message that I think will have the most impact,” Slavin says, cuing a PowerPoint presentation on a beat-up Dell laptop. On the screen is the image of a bright T-shirt bearing the message KILLED IN AN RPG ATTACK ON HIS CONVOY. The next slide shows the back: CPL. EVAN ASHCRAFT CAN’T VOTE. Hundreds of the T-shirts—one for each lost soldier—will be sold, at cost, through the site signalorange.net, complete with instructions to gather at the RNC to represent the extent of American military casualties. This spectacle, Slavin believes, could make a difference. “If there’s anything we learned from 2000,” he argues, “it’s that a few votes can win an election.”

Between the permit–and– Porta Potti pragmatists like Cagan and the romantic fabulists like Jonny America, there are the activists who have embraced direct action as the engine of the newest New Left. Direct-action tactics take inspiration from civil-rights sit-ins, act up’s die-ins, the destruction of logging equipment, and the blockades (and famous brick thrown through a Starbucks window) that disrupted the WTO talks in Seattle.

New York presents direct-action advocates with particular difficulties. The milder tactics, such as “banner drops” from office windows, would go unnoticed here. And the more interventionist forms, like closing a street with a lockdown, would be easily defused by the well-trained NYPD. Partly because of that, in fact, there won’t likely be a push for a coordinated shutdown. Instead, the idea is to go for many pinpricks, like unpermitted street parties, cream pies thrown in the faces of delegates, mass sit-ins, and smaller blockades of hotels and convention sites. RNCNotWelcome.org links to a “war profiteers” map of Manhattan companies (if a brick gets thrown through a window, let’s just say it won’t be Starbucks) and has been distributing lists of delegates’ itineraries and hotel accommodations, so that activists can harass and “bird-dog” them.

At the 2000 Republican convention in Philadelphia, Ruckus Society founder and Seattle-protest architect John Sellers was controversially charged with several misdemeanors (since dismissed), including possession of an implement of crime: his cell phone. Speaking by another cell phone from the West Coast, a sobered Sellers now says there’s no way New York activists can “tactically outmaneuver the most powerful police force on the planet.” So he outlines a plan that’s surprisingly tame, borrowing more from Habitat for Humanity than from anarchists in black masks: “We’re talking about giant river cleanups where we can talk about the environment, big read-ins where we can talk about what Bush has done to education.” He’s eager to show that activists aren’t “looking for some shit-fight between protesters and cops.” But he says he hasn’t ruled out aggressive actions to “prevent anyone from pimping ground zero for their political objectives.”

Organizers say over and over, in a well-rehearsed mantra, that they expect protests to be peaceful. But there are no guarantees that violence won’t taint all their work. “We’re only ever as nonviolent as the most violent and provocative thing that happens in the streets,” he says. “Even if it’s just a couple out of 50,000 people.”

That is the fear, widely felt but rarely voiced: that the long months of permit-wrangling and consensus-building will be undone by the actions of a few people bent on provoking a response from the NYPD and reveling in the chaos that would follow. This is a movement that prides itself on never telling any of its constituencies what to do, on explicitly not policing itself, which could leave many peace-minded protesters unprepared to deal with an ugly turn of events.

Neubauer has vivid memories of what happened last year at the trade protests in Miami when a peaceful demonstration, inside police barricades, erupted into mayhem. “It was just such a chill moment, everything was winding down,” Neubauer says. “Then something happened—I don’t know who started it—the cops just started firing”—with rubber bullets—“and it got more and more insane and arbitrary. It was the first time I’d ever traveled to a major protest and I was on the front lines of what ended up being this kind of hidden catastrophic event.”

Because of recent experiences like this, activists worry that many interested people will steer clear of RNC protests, leaving, in Neubauer’s words, “just the young punks”—a distorted sample of the movement, priming the event to become a kind Chicago ’68 redux. A nightmare scenario that, no matter who started it, would inevitably contrast a law-and-order president with a chaotic crowd.

On April 28, the same day photos of Iraqi prison abuse surfaced, UFPJ’s permit for a 250,000-strong rally on Central Park’s Great Lawn was rejected. The Parks Department ruled that 250,000 protesters would damage the sod—despite a recent concert by Dave Matthews that drew about 85,000, and the precedent set by the 800,000-strong anti-nuke rally that Cagan co-organized in 1982. Even the New York Post rallied to UFPJ’s defense, editorializing, “ ‘Keep Off the Grass’ appears nowhere in the First Amendment.”

“We’re only ever as nonviolent as the most violent and provocative thing that happens in the streets.”

“I’m outraged—it’s absolutely outrageous,” sputtered the normally imperturbable Cagan. She is convinced that the city has been not only negligent but “actively adversarial” to protesters. “The Police Department says they’re in charge, but we don’t believe it,” she says, alluding to the involvement of the Secret Service and the GOP itself. She adds that District Attorney Robert Morgenthau’s forecast of 1,000 arrests per day at the RNC has had “the effect of intimidating our work.”

Pushed to the brink of disorderly behavior, Cagan has issued a call to march on August 29, regardless, while launching a new campaign for access to Central Park.

So the show will go on, but to what end? All the protesters have different answers. Dobbs hopes the protests at the RNC will be viewed as a referendum on the Bush presidency and the Iraq war. Cagan believes that successful demonstrations—peaceful and massive—will bring in new activists to “help build a broader global-peace and social-justice movement.” The Reverend Billy romantically dreams that his Ninth Symphony will, in some miraculous fashion, reveal to “all consumers how 9/11 has been used to sell the war.” Sellers hopes that “disciplined, well-organized protests” will improve the public image of progressive movements, while other direct-action advocates like Jamie Moran merely aim to “annoy the living crap out of delegates,” with little regard for what happens next.

But perhaps all this discussion of what the activists will accomplish misses the point. If nothing else, protesters hunger for the chance to vent. After three and a half years of grimacing at headlines, chuckling at Jon Stewart, or forwarding “Boondocks” comics and online petitions, they will have five days to step out into the streets, stare GOP reps directly in the face (as close to one as they can get, anyway), and yell—or march, or bike, or dance, or do whatever it is they need to do. Unlike past convention protests, this one could be a kind of collective catharsis—as much a primal yawp as a political act. The mania is the message.

Neubauer says activists like himself are less interested in “trying to sway an unconvinced Middle America–type audience” and instead are “trying to create these temporary autonomous zones where we can experience a little piece of a world that we’d like to be our everyday reality. We’re doing it for ourselves. That’s a revolutionary switch.”

To which his fellow activists might raise their hands—and twinkle.