This was about as close to being a NASCAR dad as I was ever going to get, I knew, as the van rolled into the 30-degree bank of Turn No. 2 on the track at the Daytona International Speedway.

Four months earlier, in February, 200,000 race fans, dads and otherwise, filled this place to watch the famous 500 and cheer the guest starter: W., in “the kickoff” of his 2004 presidential bid, consolidating his downscale base in a slick black jacket, shouting, “Gentlemen, start your engines!” Today, however, the track, once home to white-lightnin’-running grease monkeys like Junior Johnson and Fireball Roberts, but now as corporate as everything else, was empty except for me and Sheri Valera, who grew up a bit down the road in Ormond Beach and, at age 21, will be the youngest Florida delegate to attend the GOP convention in New York.

State chairwoman of the College Republicans of Florida, recipient of the Ronald Reagan Future Leaders Scholarship, Sheri was my first delegate, the initial Bushie on my list.

It was part of an outreach project. The idea was that just because the Republican delegates were soon to launch their sure-to-be-surreal assault on the ole hometown, filling Madison Square Garden, home to Clyde, Pearl, and Ali, with teeth-brite cheers aimed at giving the war president four more years—that was no reason to hold it against them. Personally, I mean.

“Approach them as a missionary,” my wife said. Not all the delegates were Enron crooks, oil sluts, Armageddon lusters, and their Limbaugh-Hannity-programmed enablers. No, my wife said ecumenically, it wasn’t possible that every single one of the approaching delegates reflexively hated and feared the city of my birth, the city I grew up in and loved.

“Probably a lot of them have never even been to New York,” my wife said. That’s how it started, the notion to go to the heartland hometowns of the incoming Bush nominators. To arrive on their turf as a one-man big-city pre–Welcome Wagon. It made sense, since here I was, a living piece of New York, a real New Yorker, a former cabdriver to boot. An icon I was, less kinky than Woody Allen, not as obnoxious as Donald Trump, friendlier than Jimmy Breslin, and nowhere near as full of crap as Ed Koch with his typically sickening, no doubt paid, “make nice” spiel.

So what if I was from an Albert Shanker–worshiping union family that hadn’t had a Republican voter since they stepped off the boat from Romania? A uniter, not a divider, I would attempt to set GOP minds at ease, make them understand there was no need to bivouac on huge ships in the harbor as once suggested by the Neanderthal Tom DeLay. I would convince them there was more to do in New York than simply shop and scurry back to the hotel, congratulating themselves that it took Giuliani, hero of 9/11—a Republican like them—to save the city from itself.

That was the mission, to present myself relatively unvarnished and tawking like this—and to make clear that even if several hundred thousand New Yorkers would soon be gathering in the streets to tell their faux-cowboy candidate exactly what they thought of him, we were human beings here. People, just like them.

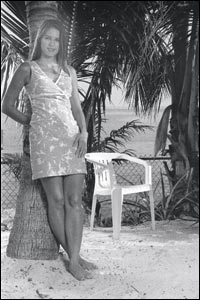

I got a list of delegates who had never been to New York from the Republican National Committee, and when Sheri Valera met me at the airport, I figured I’d been snookered. The RNC people said, “Oh, you’ll love her, she’s a star.” That much was manifest as she stood there in her jean shorts and stretchy top.

“Hi! I’m Sheri!” she said, kind of bubbly.

“Er … hi,” I replied. Sheri seemed like a real go-getter, but this was not quite what I was expecting. With that long dark hair, those beachy tanned legs and grand green eyes, and that fabulous smile, Sheri Valera looked better than Ann Coulter’s fondest dream of herself. What manner of Karl Rovean skullduggery was this?

“From the beginning, most everyone knew Sheri was special, not in any envious way—everyone loves her—but different,” says Sheri’s friend Kelly Hahne. It was Kelly’s dad, Dick, facility manager at the Daytona Speedway, who’d set up our ride around the track. On the day of the 500, Sheri, Kelly, and many of their friends went over to see W.’s campaign-kickoff event.

“We got right up front,” Sheri said. “That’s how I am. A lot of people sit around waiting for something to happen. It’s up to the zealous ones to make up for that. I’m one of the zealous ones.”

An icon I was, less kinky than Woody Allen, less obnoxious than Trump. A uniter not a divider, I would attempt to set GOP minds at ease.

The kickoff was exciting, Sheri said. But today, as we went into the backstretch not far from where Dale Earnhardt Sr.’s car hit the wall one last time, she was talking about the separation of church and state.

The issue had come up the night before, at Wednesday-night Bible study at Riverbend Community Reformed Baptist Church. Wednesday Bible class was a must, Sheri had said. And so it was that night, as Associate Pastor Tommy Clayton read from Acts 4:3–5, relating how the apostles Peter and John spoke the Gospel outside the Temple in Jerusalem. This was a bold move on the apostles’ part, said Pastor Tommy, a twentyish man in baggy jeans with punkishly close-cropped hair. “Them coming to talk about Jesus at the Temple would be like a Jew coming to preach to Hitler,” he said. This was the essence of Acts 4, Pastor Tommy said: Christians will always be persecuted for their religious—“and political”—beliefs.

What about this? I asked Sheri. What about the rehearsal we watched for the church’s “Celebrate America” Fourth of July pageant, in which congregation members, dressed up like Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae, mixed gospel tunes with songs like “This Land Is Your Land”? What about churches running voter-registration drives that often seemed like Bush pep rallies? Wasn’t it in the Constitution, the separation of church and state?

“It is not in the Constitution,” Sheri said sharply. A tenacious arguer who “takes pleasure” in crushing overconfident college Democrats in debates over affirmative action, Sheri has this church-and-state rap down cold. “The First Amendment says ‘that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.’ … The term ‘building a wall of separation between church and state’ comes from a letter written by Thomas Jefferson, plus later in the letter Jefferson says the nation should adhere to our Christian principles.”

Actually, Jefferson’s 1802 letter only extends salutary “kind prayers for the protection and blessing of the common Father and creator of man,” but Sheri had proved her point. Sheri says she got “the political bug” as a little girl when her father had her accompany him into the voting booth on Election Day, an experience she calls “almost mystical.”

Citing morality in government and low taxes as her “core issues,” Sheri takes inspiration from “strong women” like her idol, Condi Rice; Laura Bush; and Katherine Harris, who “stood up to a lot of heat” during the 2000 Florida-recount fight. On a first-name basis with presidential brother Jeb, Sheri discounts stories of blacks allegedly being disenfranchised in Jacksonville, but adds, “We probably haven’t heard the last of that,” because “Kerry will probably bring it up.”

But this election is about the future, not the past, says Sheri, a finalist in the MTV-GOP “Stand Up and Holla” competition, in which Republicans aged 18 to 24 were asked to videotape themselves speaking on issues that “best answered President George W. Bush’s Call to Service.” Sheri’s tape detailed how the Riverbend community came together during the 1998 Volusia County forest fires. “Our great American values are preserved through volunteers who have selflessly given their time,” Sheri says, a white flower pinned to her demure dark top. “President Bush understands the value of time and volunteering … ”

Posted on the RNC and MTV Websites, Sheri’s video gained a good deal of notice, some of it owing to an article from the University of Florida Blue and Orange titled “Liplocked,” in which Sheri explains why she is not only planning on saving herself for her husband but has decided not to even kiss a man until she gets married.

“What’s up with the no-kissing policy?” the reporter asks.

“To guard my heart. It protects me emotionally and spiritually,” Sheri answers.

“But if a guy would kiss you, how would you feel?”

“I’d slap him because that shows he is only thinking of himself.” Sheri says she doesn’t even like it in the movies. “In most movies, the girl is too good for the guy. I’m like, ‘Nooo! Get your hands off!! R-E-S-P-E-C-T!’ and I want to sing like Aretha Franklin.”

This engendered some snide Internet commentary, including on the July 29 edition of the blog Whizbang, where a poster with the potentially subversive handle of “Allah” opines, “Hot though she may be, do we really want a chick who refuses to kiss to be the voice of young conservative America at the convention?”

I don’t have to tell you that Sheri is a beautiful young woman,” said Roy Hargrove, senior pastor at Riverbend Community Church, whom Sheri describes as “one of the people whose ideas mean the most to me.” Pastor Roy, a casually impressive man from Rector, Arkansas (Sheri says, “That’s why he knows so much about the Clintons”), who has built Riverbend Community into an ecclesiastical presence with an annual operating budget of $2.6 million, said, “Someone with that sort of outward beauty might allow themselves to be seduced by it. But Sheri retains her inward life, her drive. That can be a powerful force. I can see Sheri becoming the first woman president of the United States.”

Told this, Sheri blushed. “Pastor Roy said that? That’s very flattering. Well, he might be right.”

But outside of working on beating out the hated Hillary, what did Sheri plan to do when she came to New York? We were talking about it over steak-and-portobello fajitas at Chili’s in Ormond with Sheri’s mom, Reatha, who will accompany her daughter to the convention. A friendly, charming woman in her forties who bakes a heck of a banana bread, Reatha hasn’t been to New York either. “The closest we got was driving by. We were going 60 miles an hour but still locked the doors and windows.” This time, Sheri and Reatha agreed, would probably be more fun.

This opinion was shared by several of Sheri’s friends who joined us for dinner after Bible class. Proud that Sheri would represent them at the convention, several noted how instructive it was to hear Pastor Tommy talk about Christian persecution in light of the massive protests likely to greet President Bush in New York. “He’ll be the underdog, that’s for sure,” one said. Beyond that, there were a lot of suggestions about what Sheri and Reatha should do in the Big Apple. While the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty were pretty cool, everyone agreed the city’s number No. 1 attraction was ground zero.

“Right,” Sheri said. “That place belongs to all Americans.”

This was the commentary that tried the resolve of even the most committed New York City missionaries. Because I didn’t feel like ground zero belonged to “all Americans,” certainly not the sort of “all-Americans” who took it as a moral imperative to keep George Bush in the White House. Ground zero belonged to New York, to the people who died there and their families, to those who rode the F train every morning and never once looked at the skyline without noting the absence of those not particularly beloved buildings looming over the Brooklyn Bridge.

It was a question everyone asked out here: Where were you that day? I had a compelling answer, or at least one people usually find compelling. Because I was there. Not when the planes hit, or when the buildings fell, but a couple hours later, when, in the horror and confusion, no one kept me from walking through the twisted rubble, right to the pile of dust that would come to be called ground zero. “Where are the buildings? Where are the people?” I asked a weary firefighter. “Under your shoe,” was the answer.

I told my WTC story to the delegates because—more than what restaurant to eat in or what play to see—this seemed to be what they really wanted to know about New York. Reliving that day is always emotional for me, and hearing about it was emotional for the delegates. If there was any real bond between us, it started there, as legitimate as it was that day.

Yet I begrudged them their emotion, their sense of outrage that 9/11 had been an attack on them, too, a thousand miles from the half-empty firehouse of Squad One. Perhaps it was provincial—should only Hawaiians have been pissed about Pearl Harbor?—but it bothered me that 9/11 had redefined the city in the minds of those who hitherto would have agreed with John Rocker’s assessment of the 7 train.

It has been declared sacred ground, a place of pilgrimage, separate from the real city. For many, Republican delegates certainly included, ground zero has acquired the patina of a Revelations-style Valley of Decision, with the steel girder “cross” found in the wreckage taken as proof of where God’s allegiance lies in the War on Terror. Don’t they know that cross is a fireman’s cross, a cop’s cross, an ironworker’s cross—a Democratic cross, if it’s any kind of cross at all?

Thinking about it was enough to make you shake your head, yet again, at the audacity of Bush’s bringing his convention here, so close to the anniversary of that day. Like he imagined he was really invited.

On the other hand, wasn’t it sheer bad manners to do anything but say “thanks” when someone like Wes Rice asserted, “I think everyone in the country became a New Yorker that day”?

Then again, Wes Rice, a delegate from Zephyr Cove, Nevada, on the shore of Lake Tahoe, and his wife, Eileen, also a delegate, are another kind of Republican.

“I’m a Republican because my father would roll over in his grave if I wasn’t,” says Eileen, who works as a nurse in the local emergency room and has never had a problem making herself heard even if she is only five feet tall. It was her orphaned dad, a man who pressed his pants underneath flophouse mattresses so he could keep looking for work even while hoboing around the country (later becoming an electrical engineer), who taught her the value of self-sufficiency, Eileen said. This was what the Republican Party was really about, Eileen declared.

True political conviction came not from handed-down ideology, or some loudmouth rant on the radio, but from life experience, Eileen said. Back when she was working at the Arcadia Methodist Hospital east of L.A., “they brought in two victims of Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker. These were elderly ladies, dismembered. One had a pentagram carved into her leg. I didn’t know how I felt about the death penalty, but then I knew: Richard Ramirez had to die. Even now, thinking of him living a fat life in prison with new teeth paid for by tax dollars sets me off.”

Politics was about “trying to stay in the real world,” agreed Wes Rice, a large, wry-humored man of 61, who spent 28 years in the Pasadena, California, Police Department, many as chief of detectives, and who now pilots a patrol boat on the lake for the Douglas County Sheriff’s Department. To this end, Wes’s most difficult task as chairman of the Douglas County (population: 44,000) Republican Party is “beating back the single-issuers … mostly the anti-abortion people.”

With five grown daughters and ten grandchildren between them, he and Eileen “maintain a strong sense of spirituality,” says Wes. “I just don’t think you have to go around telling everyone about it.” Religious beliefs were simply not a political issue, said Eileen, a strong supporter of stem-cell research (“Nancy Reagan, you go, girl”). It was in the middle of this conversation that Eileen, who has been known to enjoy an episode of South Park, announced she was about to use “the dreaded M-word.”

“Not the dreaded M-word,” Wes exclaimed in mock horror. “Rush says there’s no such thing as a moderate Republican.”

“Oh yeah?” replied Eileen. “Just try me.”

What it came down to, said Wes, was “we may be Republicans, but we’re not nuts.”

“Going to New York is kind of like a nightmare that became a dream,” said Wes, who once thought of the city as “this place where people closed their windows while women called for help in the alleyway.” Now Wes, an admirer of Giuliani-style policing, ran his finger with gleeful expectation along the orange path of the D train on the subway map I’d brought to Zephyr Cove. Just that morning, the UPS man had arrived with the “official welcoming packet” from the RNC. Several letters beginning with “Dear Delegate” offered entertainment choices including Broadway plays. Mostly, though, aside from eating “some really good corned-beef sandwiches,” the Rices were most looking forward to taking part in the nomination of George Bush.

“You want to know why I like George Bush?” Wes Rice asked me as we puffed on sweet Jamaican cigars in the crisp, piney air outside his house.

“Last month, he was in Reno. We got onstage. It was such a thrill to be 25 feet from a sitting president. I was able to make eye contact with him. He seemed very genuine. I felt he would never knowingly lie to me. Maybe it is a cop thing. On the street, you’ve got to trust your assessments of people or you could be in serious trouble. I trust myself on George W. Bush.”

Like a moron, I’d left the lights on in my rental car. We were charging the battery, using Wes’s Cherokee. Cigars and jumper cables, these were “man things,” said Eileen. She was going to bed. It had been a big day, driving around the lake, checking out Emerald Bay, stopping by the Coast Guard station where the chief officer reported how they’d picked up “a man of Middle Eastern descent behind our HAZMAT shack.” It turned out to be a false alarm, but you couldn’t be too careful, even 6,000 feet up, in such beautiful country.

“No need to go to heaven,” said Wes, expressing his fealty to the great lake. “We’re already in paradise.” But it was a paradise with a dark side, said Wes, relating how Ed Callahan, his patrol-boat partner, fell overboard in a storm and drowned on Memorial Day weekend in 1998.

“The water was 44 degrees,” Wes recalled. “You can’t last long; the hypothermia shuts you down. I tried to save him, but it was impossible. I was passed out when they dragged me back into the boat.”

It was a sad, rueful tale, how Ed Callahan, who made it through several tours of duty in Vietnam, came to die in the seductively blue waters of Lake Tahoe, where college students came on weekends to shatter the silence in their Ski-doos. It was the sort of story men sometimes tell when they’re trying to get through to each other, nodding at the ineffableness of it all. In another time and place, Wes and I, similar in age, laughing at some of the same things, could have been friends.

Too bad we had to talk about politics. Wes had warned against it. “I’m not going to change your mind, and you’re not going to change mine.” But I’d come 2,800 miles because he and Eileen were Republican delegates, so what else were we supposed to talk about? I couldn’t figure how Wes, who seemed like such a smart, soulful guy, could look in the eyes of George W. Bush, orbs I found beady and vacant, and decide this was a man he could trust.

“If there is anything that really turns my stomach, it is a liberal man,” said Rick Gue. I looked to see if he was staring at me.

A lot of things Wes said didn’t make sense to me. He said, “I know those weapons of mass destruction are there. They are there, or in Syria, and they will be found.” He said, “John Kerry represents everything I hate. Who knows how many American lives people like him and Jane Fonda cost us protesting the Vietnam war?” He said whatever happened in the 2000 Florida vote count was worth it, because, as he said his Democratic friends agreed, “heaven help us if Al Gore was the president on September 11, 2001.”

Then again, Sheri Valera nodded when one of her friends from Riverbend said, “Kerry’s war record is a lie. Bush was training to go over there, and if they called him, you can bet he would have been a better soldier than Kerry.” Even Eileen Rice, so flinty under fire, said, “You’ve got to have faith that the government knows more than we do and is doing the right thing.”

These were the views of the very nice people I had set out to welcome to New York. Wes Rice was correct. It would have been better if we didn’t talk about politics.

It was a matter of what version of America you believed in, I thought, driving along the banks of the Ohio, great heartland river of flatboats, murder ballads, and shuttered Appalachian factories. I like my America big, a sea-to-shining-sea big, a boiling regionalized stewpot, freaky off-angles seeping between the corporate cracks. I deplored the idea that the city should secede from the country. My America is not complete without both Joey Ramone and George Jones, to say nothing of Dr. Dre, Emerson, and Randy Weaver. How could New York be its own nation? It didn’t even have one truck stop. My America needed America.

When the RNC gave me its list of delegates, they kept referring to my final interviewee, the auditor and tax assessor of Lawrence County, Ohio, as “Moose.”

“What’s his real name?” I inquired. I didn’t want to call up and just ask for Moose.

“Ray,” they said. “Ray Dutey. But everyone calls him Moose.”

“His name is Moose Dutey?”

“That’s his name.”

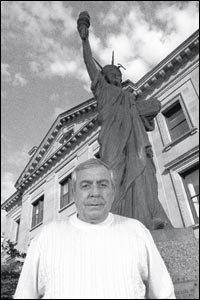

And there it was, RAY T. DUTEY, AUDITOR, on three different wooden signs outside his second-floor office in the Gothic Lawrence County courthouse in downtown Ironton, once the center of the Southern Ohio pig-iron empire but now one more mining town hanging on by the skin of its teeth. Resplendent in a beige suit with boldly matching gold tie, Moose bounded out of his oversize chair to greet me. No way he’s more than five-foot-four. Smiling, Moose said, “I guess now you know why they call me Moose.”

If all politics is local, then Moose Dutey, who grew up playing on the river sandbars, was politics itself. Recently turned 74, one of ten siblings, Moose has been in Lawrence County public life for 55 years, starting as a councilman in his native Coal Grove, about three miles east on U.S. 52. In 1960, he was elected mayor of Coal Grove (“won by 146 votes,” Moose recalls), and was reelected in 1962, during which time he managed to raise enough money to replace the fire truck the town had been using since 1936. In 1964, he was elected county recorder and moved to the courthouse in Ironton, where he’s worked ever since.

Never beaten in an election, Moose is chairman of the Lawrence Country Republican Party. On his 50th year of public service, the county threw him a parade. They renamed his street, so now he lives at 200 Dutey Drive. He could run for another term in 2006, but he figures he’s done. “I’m going to retire,” Moose said.

Of course, Moose Dutey has never been to New York. Outside of when he was sent overseas in the Korean War and stopped in San Francisco, Moose said, “I haven’t been around the country that much.” He hardly even goes to Kentucky, though the state, right across the river, is visible from his office window. When he does cross the bridge, it’s usually to eat at Applebee’s or Ruby Tuesday’s. Ironton, a shrinking town of 12,000, where a quarter in the parking meter buys you five hours, and the sign in the pool-hall window says FIGHTERS WILL BE PROSECUTED, doesn’t have “a single decent restaurant that you’d want to eat in.”

Fondly recalling several New Yorkers in his infantry unit in Korea, “guys with lots of colorful expressions,” Moose said he’d wanted to visit the city since he first watched the ball drop on New Year’s Eve in Times Square on TV. “All those people in one place. That always amazed me.” Happy to hear that his hotel, the hulking Marriott Marquis, is in the middle of the Crossroads of the World and looking forward to visiting Yankee Stadium (the Indians are in town), Moose still couldn’t believe he’d been chosen to be a delegate. “I’m small-town. I didn’t even know I was under consideration,” Moose said in his reedy, relentlessly modest drawl.

“You know, we’ve been Republicans here a long time, back before Robert Taft. We’re not rabid. But I like President Bush. I like that he takes a position and sticks to it,” said Moose. No policy wonk, Moose reeled off the names of failed or failing local businesses (“Dayton Iron Company … out of business … Allied Chemical … out of business … the Ammonia plant, used to employ 2,000, out of business”) and then concluded, apparently without irony, that “they say the economy is picking up.” As for Iraq, Moose said, “That’s slackened up … you don’t hear much about American casualties now.” I handed Moose a newspaper listing the names of twelve U.S. soldiers killed in recent days. Moose looked at the article grimly. “I hadn’t seen that. I’ve been real busy this week, over at the fair.”

By this Moose meant the Lawrence County Fair in Proctorville, which was where we went next, walking across the muddy tractor-pull patch to check out grand-champion hogs and steers. In election years, local politicians bid up the prices on the winners of the livestock contests. The Republicans had gone “sky-high” for the 4-H’s grand-champion hog. The champ steer was way outside the budget.

Moose was not averse to munching a funnel cake or two, but he went to the fair in his capacity as county party chairman, to keep tabs on his candidates. Most of them were there, seated at the pin-neat Republican booth, beside giant pictures of Bush and Cheney. There was Cheryl Jenkins, secretary of the local Republican club, Rod DePriest, candidate for county treasurer, and Richard Holt, a fresh-faced 24-year-old African-American Republican who was running for the legislature even though Lawrence County has a black population of less than 2 percent. Holt said he was running “for the experience.”

As soon as Moose arrived, every candidate, many of whom had known him for decades, emerged from behind the booth to shake his hand. “He’d never let on, but Moose is the littlest big man around here,” said Sharon Hager, running for Dutey’s old recorder job. Moose had taken her “under his wing,” said Sharon, towering over her benefactor. “In Lawrence County, Moose Dutey means something,” Sharon said.

That much was clear as we picked our way through the cow pies toward the Democratic booth. The Democrats, sitting around like a bowling team, had a picture of Kerry, but it was on the floor, upside down.

“Moose!” called out George Patterson, an imposing man in his fifties. The Democratic county commissioner, Patterson, a Lawrence County version of Philip Roth’s Swede Levov, was remembered, Moose said, as “one heck of a football player, maybe the best we ever had.” Still in Coal Grove, still best friends with Moose’s younger brother, Patterson said it wasn’t easy being a Democrat here. “Even my wife voted for Reagan.”

But this time it would be different. “I’m getting six this time, Moose.” By this Patterson meant Democrats would win half of the countywide offices.“Don’t be silly,” Moose said with grinning dismissal. “You’ll be lucky to get two, George, you know that.”

“Three?” Patterson asked, bluster diminishing.

“Two’s all I can give you. Not another stitch.”

The fact is, Moose said later, the Democrats might win only one, Patterson’s own race, for county commissioner. The Republicans were running Kenneth Ater, son of a well-known Lawrence County judge. Ater was putting up billboards, getting his name on pens and T-shirts. But he wasn’t going to beat George Patterson. “He’ll get beat real bad,” Moose said. Asked if he is ever wrong about such things, Moose winked and said, “Hardly never.”

Moose Dutey was a kick. I liked his self-effacing manner, and that he was secretly a killer of a local pol. I liked that he pronounced Bush’s name “Booo-ish.” So what if he didn’t believe in evolution? There is a place in my America for Moose Dutey. I hoped there was a place in his for me.

That night, Moose had been invited to hear Laura Bush call the upscale, hilltop Chesapeake, Ohio, home of Rick and Kathie Gue. “ ‘Goo,’ they pronounce it ‘goo,’ ” Moose said as we went up the long driveway, passing a sign saying THE GUES WELCOME YOU TO BUSH COUNTRY.

Kathie Gue, a thin, perky blonde woman in what looked to be her forties, was “real gung-ho for Bush,” Moose said. This seemed true as she greeted us by jumping up onto a chair and shouting “W.!” This was the cue for the 25 or so people, both young and old, many wearing elephant-shaped jewelry, to jump from lawn chairs arrayed in the Gues’ driveway and yell “Four more years!” This call-and-response was repeated as Mrs. Gue passed out slices of red-white-and-blue cake. Chowing down, Moose and I chatted with the head of the Lawrence County Chamber of Commerce, Bill Dingus.

Dingus, Dutey, and Gue: They didn’t have this back in Brooklyn. In the pleasant twilight air, even Laura Bush saying, “All of you know what makes George such a great president … It is his heart. I know his heart,” sounded faintly bearable.

It was only when the Gue family began speaking that things began to unravel. One of the Gues’ four strapping sons made reference to “thousands of babies murdered” since Roe v. Wade and called for everyone to “Hannitize the vote,” by making sure everyone they knew registered. This was seconded by Kathie Gue, who said how upset she was that “only 22.5 percent of Christians” voted in 2000 and how that “had to change.”

Then came Rick Gue, a salt-and-pepper-haired man dressed in a dark-blue suit, who, after thanking “the Lord” that he’d been able to raise “four Christian, conservative sons,” said, “If there is anything that really turns my stomach, it is a liberal man. The idea of raising children without Jesus Christ and conservative values as the centerpiece of family life is unthinkable to me.”

Earlier in the evening, as a visitor from a far-off metropolis, I’d been asked to speak and said how happy I was to be here, in the Ohio River Valley. Now I looked up to see if Rick Gue was staring at me or not. But by this time, he’d slapped a plastic George Bush mask onto his face as everyone jumped out of their lawn chair to shout “Four more years” yet again.

We rode back to Ironton, passing the rusting factories along the river, saying little. Finally, Moose, attempting to lighten the mood, offered that he sure was looking forward to visiting New York, to see my hometown, just as I’d seen his.

“I’ll be happy to see you,” I said. “But I won’t be happy to see Bush, or a lot of these people.” It just slipped out, what I thought, what most people in New York thought: that the Republicans were coming only because of 9/11, and how creepy it was that Bush would use this supreme heartbreak for his own personal gain. I told Moose that and immediately regretted it, because that wasn’t what I’d come to Ohio to say.

I could feel my heart, which I’d imagined to be an infinitely expanding canvas—like New York itself—close down. I had my America, and, sad to say, lots of Americans, people I liked, appeared not to fit inside it. Not now. Not in 2004.

Moose, noting my discomfort, said, “It is true that I feel more comfortable over at the fair. Those are the people I grew up with. But Lawrence County is filled with all kinds of good people, good Republicans. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion. That’s what the country’s all about.”

Couldn’t argue with that, I supposed, a few days later, back in the city. I’d done what I could, tried my best. Made nice. Now I can go to Central Park and scream for Bush to go home, like everyone else.