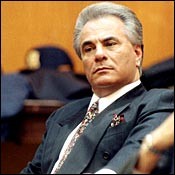

Vanity, grandiosity, and below-average intelligence are usually a fatal combination. In John Gotti’s case, they serve as his epitaph. Gotti will go down in history as the man who did more to destroy the old Italian Mafia than anything since Robert Kennedy, the rico statute, the Witness Protection Program, and Joe Valachi.

By giving the finger to the government, Gotti brought surveillance, informants, and hidden microphones down upon a secret criminal society that did not want any extra scrutiny.

John Gotti was the don-as-diva. He was in love with himself and equated his ego with all of La Cosa Nostra. He was a throwback to the first narcissistic, starstruck hoodlums – Bugsy Siegel and Al Capone, who also didn’t understand boundaries and were addicted to publicity.

John Gotti broke every old-world, old-school code of the American Mafia. He killed his own boss (Paul Castellano) in a hit never sanctioned by the mob’s Commission, using some assassins who weren’t even “made men” at the time of the ambush at Sparks Steak House.

Gotti’s original Queens crew dealt heroin, in violation of the Gambino family’s prohibition against drugs. Gotti helped put the white poison from the poppy into every city neighborhood and park. He recruited heroin dealers to murder Castellano.

Gotti, as an American-born child of pop culture, wanted to be famous, not just rich and powerful. He went to trendy discos in $2,000 suits. He talked about “my public.” When Gotti made the cover of Time magazine, he hung a blowup of the image in his social club. He also made the covers of People, The New York Times Magazine, and New York.

The old-school mob bosses understood omertà, the code of silence. They were born in Sicily, or the Italian Mainland, or, in Meyer Lansky’s case, Poland. They hated publicity. They never wanted to be mentioned in a national magazine, much less on the cover. They knew it meant trouble. Aniello Dellacroce, Tony Salerno, and Chin Gigante did not have publics. In the fifties, the libraries of tabloid newspapers didn’t even have a picture of Carlo Gambino in their files. Secrecy and discretion were in the blood of the earlier generations of godfathers.

John Gotti was the first mob boss influenced by the popular culture of movies, media, image-making, and publicity. Nobody ever called Thomas Lucchese “The Dapper Don.” Paul Castellano never waved to his public outside a social club. Fame was the last thing on earth those gangsters wanted.

Gotti had seen the Godfather films, and when he became the boss in 1985, he started performing his life as if he were playing a role in a movie. According to his underboss, Sammy Gravano, Gotti got a haircut, a blow-dry, and had a barber snip the hairs in his nose and ears every morning. He wanted to look perfect for every camera.

When Gotti strutted down Mulberry Street, the most famous gangster since Capone was probably hearing a rising, romantic film score inside his head.

Carlo Gambino never even went to the movies! But Gambino was shrewd enough that he was never caught on tape talking about a crime. Neither was Chin Gigante. Neither was Anthony Spero.

John Gotti, in contrast, was recorded on tape committing crimes and acknowledging three murders. The FBI had a bug in the apartment above the Ravenite Social Club, and that’s where Gotti admitted ordering the murder of porn king Robert DiBernardo, Louie Milito, and Louis DiBono. Bang! Three homicide counts in a rico conviction! Gotti’s boastful lack of discretion is what ended his career. Old-schoolers like Gambino and Santo Trafficante were never convicted and died of natural causes as free men.

Gotti did not exactly go to Harvard Business School. He dropped out of Franklin K. Lane high school at 16. He was an adequate hijacker who made his bones by being part of a team that executed an Irish hoodlum named James McBratney in a Staten Island bar in 1972.

He was also a compulsive gambler. Meyer Lansky owned casinos but never gambled himself. Lansky had the emotional discipline of a professional.

Gotti was never an original thinker or executive; his idea of modern management was torture.

When he became boss, Gotti played right into the hands of the FBI. He made all his capos report to him like robots every Tuesday night at the Ravenite club, near the corner of Prince and Mulberry. All the FBI had to do was take pictures and they had an organization chart of the family’s new structure. The meetings were a show that had no real purpose. They let Gotti feel big.

In the early eighties, Gotti let his Queens crew get into heroin trafficking, against the rules of the family established by Castellano. Castellano knew that drug dealing would bring rico heat down on his gang. Paulie was more at home in a bank than a social club.

The main reason that Gotti killed Castellano when he did was that Castellano was about to find out, through pretrial-discovery materials, that Gotti’s brother Gene was dealing in heroin. It may have been kill-or-be-killed for the Gottis in December 1985.

It was both vanity and grandiosity that led Gotti to install his son, John Jr., as the acting boss of the family when he went to prison for life in 1992. He felt he could control the family himself from prison, through his son.

When Junior went away, John Gotti made his brother Peter the acting boss of the family. Peter, a former sanitation worker, was indicted on June 4 for racketeering, along with another Gotti sibling, Richard.

Junior had even less leadership skill than the father. Junior was a steroid-using hothead with no planning or negotiating talents. John Gotti Sr. demoralized the Gambino crews by imposing his son as a stooge leader, instead of letting merit play some role in his succession. And besides, Junior was seen as illegitimate by the old-timers because his mother was Jewish.

In his book on Sammy Gravano (Underboss), Peter Maas recounts the anecdote of how a proud Gotti informed Chin Gigante that his son had just been made.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” the Chin replied, which is convincing proof that he was less crazy than Gotti. None of Gigante’s sons were ever made. And none of Castellano’s sons were ever made. The fathers sensibly aspired to “legitimate” businesses for their progeny.

Gotti’s ego and his identification of his fate with that of the whole mob also contributed to his biggest blunder. In jail awaiting trial, Gotti told Sammy Gravano that Gravano couldn’t have his own lawyer and couldn’t have a severance for his case.

These unappealable decisions made Gravano think he was being set up, and convinced him to become a witness against Gotti at trial.

Nick Pileggi, who co-wrote Goodfellas, thinks the Godfather films influenced Gotti too much.

“The Godfather gave Gotti a romantic view of his own brutal life,” Pileggi says. “Those films gave Gotti a sense of dignity and history. They changed the way gangsters thought of themselves. In their heads, they became Brando and De Niro.

“But the problem,” Pileggi went on, “is that Gotti was just a high-school dropout and a degenerate gambler. So no matter what Hollywood images were in his head, he was still a throwback who took the mob back to the twenties. He just didn’t understand business and banking the way Castellano did. Gotti did become famous, but he didn’t earn the way Paulie did.”

Gotti was certainly not the first gangster who sought celebrity. Joe Colombo went public in the late sixties, organizing rallies against the FBI and protesting “anti-Italian discrimination.” That’s why the other mob bosses had him assassinated at one of his own rallies. His high profile was provoking too much attention from the government.

During Gotti’s seven-year rule, the mob declined, becoming just another gang, forced to compete with Russians, Albanians, Israelis, and Colombians for an ever-shrinking slice of the crime market.

The traditional Mafia will always have some power as long as “two bullets in the same hole” can gain some economic advantage. But its prime has passed.

John Gotti is dead. His son is in prison, serving five to seven years for shaking down topless clubs – forties thuggery. Gene Gotti is serving 50 years for trafficking heroin. Gotti’s son-in-law, Carmine Agnello, just pleaded to nine years for racketeering, after he committed crimes while being tape-recorded by the government. And now the other brothers, Peter and Richard, may also be on their way to prison.

Gotti’s old clubhouse, the Ravenite, where he blabbed into the FBI’s hidden microphones, is now Amy Chan’s handbag-and-accessory shop.

Like a lot of tragic figures in literature, Gotti hurt the two things he claimed to love the most – his blood family and the Gambino crime family.

John Gotti was a very American mook. He spent seven years as Godfather and twelve years as an inmate.