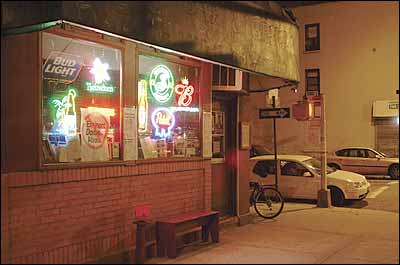

Donald O’Finn remembers right where he was the moment he learned that some billionaire developer named Bruce Ratner had plunked down $300 million to buy the New Jersey Nets in the hope of transporting the team to Brooklyn. He was in Freddy’s, the bar he manages, the same bar he’s in tonight: a coppery-lit former speakeasy in Prospect Heights that sits on the site Ratner wants to raze to build a Frank Gehry–designed arena. “I was off that night, just drinking,” he recalls, pouring a healthy Maker’s on the rocks and thinking back to that bitter January day. “We saw it on the news, and within minutes people started showing up, their eyes all lit up, saying they’d tie themselves to the door before the wrecking ball comes.” He sighs. “It was incredible.”

That was the beginning. Freddy’s quickly morphed from a cult hangout to a hub of protest, the spot where residents vented and consoled and drank a little more than usual. Fund-raisers were held, vitriolic letters penned—to editors; to David Stern, the NBA commissioner; to Bloomberg and Hillary and Chuck. The random kitsch on the walls—a stuffed marlin here, a broken clock there—was joined by posters reading YOU CAN TAKE THE KEYS TO THE PROPERTY … WHEN YOU PRY THEM FROM MY COLD, DEAD HAND. The back room, typically a spot where people shoot pool or check out local bands, became an impromptu shrine, the walls lined with portraits of residents convinced their lives would be unhinged by the plan—twentysomethings, seniors, a toddler, all with their middle fingers proudly extended.

Freddy’s, in effect, became not just the epicenter of the anti-Nets movement, but a metaphor for all of Brooklyn’s anti-development angst. Over the past decade, the borough’s quiet streets, regal architecture, and fuhgeddaboudit charm have been embraced by those priced out of Manhattan, but it wasn’t until this year that Brooklyn seemed on the cusp of an irreversible extreme makeover. Behemoth condos are sprouting up along the Williamsburg and Greenpoint waterfronts. A movie studio is being shoehorned into the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Corporate glass towers will soon rise downtown. And a cruise-ship dock may appear in Red Hook, where sunburned Carnival customers will stumble out to explore … what? Ikea? Brooklynites are gripped by an acute panic: This time, the outer borough really might become the new Manhattan. Or the new Long Island.

“All you gotta do is look at what happened over on Atlantic Avenue,” says Don, bringing up the nearby swath of real estate now occupied by the Atlantic Center mall (Old Navy, Burlington Coat Factory, Marshalls) and the newer Atlantic Terminal Mall (Target, Chuck E. Cheese, a Houlihan’s on the way). “Those are Ratner developments, and what’d they bring? Quite possibly the ugliest, most frightening things Brooklyn’s ever seen.” He thinks for a moment. “It’s not like we’re against all new construction. It’s that we’re already developing—slowly, organically. I couldn’t believe Ratner had the audacity to talk about this area like it was uninhabitable, like once he was done, people would actually want to live here.”

Also at the bar tonight is Marla Humphress, a native of Kentucky, a vaudeville-burlesque performer and seven-year regular who, six months ago, started working behind the bar because that’s the sort of place this is. She says that the anti-Nets fervor has subsided in recent months—fewer fund-raisers, far-less-heated debates—and she’s just fine with things getting back to normal, however long that lasts. “Know why?” she says between sips of a Powers Irish Whiskey. “Ever since the Nets thing went down, there are students from Columbia who come in here once a week, to write a pretend article for their journalism class. We’ve become a school project, a tourist attraction.” She takes a deep breath, finishes her drink, and turns to Don. “Can I have another?”

For the past few months, Ratner’s plan has been locked in a political and bureaucratic stalemate, though it has the support of key city officials and could well happen within the next few years. “At this point, we’re just waiting for any information we can get,” says Don, topping off Marla’s glass. “We’ve been hearing rumors—a guy came in here who knows a guy who works for Ratner—that we’re not gonna be demolished. Maybe we’ll be this lone bar in a parking lot—who knows?”

But what if the wrecking ball does come? What then? “Oh, man,” says Don. “I really think something’ll be lost. Bars like this used to be vital—when you settled a town, you put up a bar before you put up a church.” He and most of the regulars, Don says, aren’t political types—they’ve never been the sort to take up causes. “I think part of why so many of us became so occupied protesting was because it’s a way to avoid asking what we’ll do if that arena gets built.”