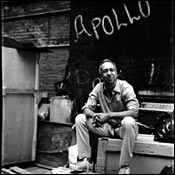

About four miles south of the Apollo Theatre, home of the new musical Harlem Song, George C. Wolfe, the show’s creator, is sitting in his softly lit second-floor office at the Public Theater getting ready to go to a rehearsal. It is a steamy summer afternoon near the end of June, but Wolfe, the Tony-winning writer, director, and producer, exhibits no signs that he is wilting from the heat of the day or the pressure of opening a new show.

Instead of obsessing, the slim, loose-limbed Wolfe is doing one of the things he does best: telling stories, stories about putting Harlem Song together. “Oh, God, I had this open call for the show that started at 10:30 in the morning and didn’t finish until 10 at night. For close to twelve hours, we had people lined up to dance and sing. It was astonishing. I found one woman so intriguing and really moving,” he says, shifting in his chair like a nervous teenager.

“She came out onstage, dressed very nicely, and she said, ‘I’ve never done anything like this before.’ She sang a song, and it was clear she was not a performer. And I was wondering, did she sneak away to do this? Did her children know she was coming? Did her husband know? Did she come with her girlfriend? I just love the fact that she did it.”

Then he tells the story of an Asian woman at the audition who walked out onstage and sang “Precious Lord.” “Her performance was filled with these gospel riffs and the whole thing. And she didn’t speak a word of English. It was just so wonderful.”

One reason Wolfe isn’t feeling the pressure is that he’s handled it before. He’s had ten shows on Broadway in the past ten years, including (along with a couple of flops) such diverse hits as Topdog/Underdog, Elaine Stritch at Liberty, Bring in ‘da Noise Bring in ‘da Funk, and Angels in America. But, exuberance notwithstanding, Harlem Song, in its first week of previews, is the biggest challenge he’s faced in years. It is the first time in the Apollo’s history that it will be home to a show with an open-ended run. Harlem Song is scheduled for seven performances a week, three on Saturdays, two on Sundays, and two on Mondays.

Raising the stakes, Wolfe has chosen to tell the social, cultural, and by extension the political history of Harlem from the Roaring Twenties to the present within the confines of a 90-minute musical revue that is striving for the broadest possible appeal. “I know there’s going to be criticism,” Wolfe says equably. “There are a lot of people who believe they own the history, the mythology of Harlem. You know, they believe it’s their story. But I have to tell the stories that intrigue me. The piece is about the energy of the day and, ultimately, about the regenerative power of community. That gave me my clues about what I needed to do.”

This is not a typical Broadway or Off-Broadway opening – in fact, the show is, in a very real way, about the future of Harlem. And it carries with it the hopes and expectations of the community. “This is not just about Harlem Song or the Apollo,” says Derek Johnson, a Harlem resident and former AOL Time Warner executive who left his corporate post to head the Apollo Foundation and to direct the renovation and (he hopes) the resurgence of the forlorn landmark. “This can be a transforming, catalytic event for the community that will have great spillover effect for all of the other businesses.”

Harlem Song comes at a critical point in Harlem’s still-nascent resurgence. After almost ten years of significant capital investment in residential and commercial projects, the community is at a kind of crossroads. Five years ago, Harlem, which has about the same population as Vermont, had no supermarket, no video store, no place to get a salad at lunchtime, buy a television, or go to the movies. Private investment was kept away for years by Harlem’s political cronyism. “But that’s all changed dramatically,” says developer Bruce Ratner, head of Forest City Ratner, which is completing a 300,000-square-foot retail and office building on 125th and Lenox Avenue called Harlem Center. “And you have to give the credit to Governor Pataki. You wouldn’t have expected it given that there’s not a lot of Republican votes uptown. But he and his people took the politics out of what was being done up there.”

Then a Pathmark supermarket, a Blockbuster video store, movie theaters, a mall, and a variety of other retail outlets opened up. And now that the path has been cleared, there are at least a dozen new commercial developments under way. At the north end of Central Park will be a 220,000-square-foot cultural and office complex slated to house the corporate headquarters of Edison Schools and the Museum for African Art.

Gotham Plaza on 125th Street is due to open in a matter of weeks with its own payload of chains and national brands. On 135th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, in what used to be Smalls’ Paradise, the Reverend Calvin Butts and the Abyssinian Development Corporation are building a new home for the Thurgood Marshall Academy, a successful public school started by the Abyssinian Baptist Church. Over on the east end of 125th Street, Potamkin has planned an auto mall that will fill three blocks from 125th to 128th. There’s also Gateway Plaza, a retail center on 125th near Lexington; as well as the Hue-Man Bookstore, at 125th and Frederick Douglass Boulevard, specializing in black history and culture, due to open in a few weeks. And lest you think the picture seems somehow incomplete, Harlem already has a Starbucks.

But retail development has its limits, particularly on 125th Street, which will, from river to river, very shortly be almost unrecognizable from what it was a few years ago. Consequently, people are now starting to look at the future, at the next step. And that is where the opening of Harlem Song and the $54 million renovation of the Apollo Theatre are expected by many people to play a crucial role.

If phase one of the Harlem revitalization was eliminating the impediment of the local politicians (who were stunningly inept, except for maintaining their own power) and phase two was that first burst of commercial and residential development, what shape should phase three take? “The real issue now is to get people to come up and spend money here,” says Derek Johnson. “For too long we’ve been recycling the same dollars in this community.”

The way to get people uptown, particularly when significant psychological barriers still exist for many, is to give them a compelling reason to go. “The crux of this whole Harlem economic revitalization has nothing to do with the Disney store or any of the other chains that are opening on 125th Street,” says Michael Eberstadt, owner of Slice of Harlem, a pizzeria, and a creole restaurant named Bayou, both on 125th. “It’s just more retail, and who cares? Nobody is coming uptown for the glory of shopping in overpriced sneaker stores on 125th Street.”

Eberstadt, who is white, opened his first Harlem restaurant a little over four years ago after working in social services (he ran a soup kitchen) and completing a master’s in public policy at Columbia. He believes his experience with Bayou illustrates the difference between Harlem’s current economic reality and its potential.

Eberstadt has struggled with Bayou for two years and is just beginning to break even now, though the restaurant has gotten lots of good press (in part because he has regularly catered events for 125th Street’s best-known resident, William Jefferson Clinton) and word of mouth.

“People might come up here the way they’d go to an interesting Indian place in Jackson Heights, or an Italian restaurant in Bensonhurst,” Eberstadt says. “They’ll go once for an unusual experience and to tell their friends they did it, but they won’t come a second time, and repeat business is where the money is in restaurants.”

But when there are shows at the Apollo, like recent appearances by Whoopi Goldberg and by Wynton Marsalis and his Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, Bayou is packed. “The real underlying economic asset of Harlem is that it’s the capital of African-American culture, past and present,” says Eberstadt. “And moving forward now, that’s what everything else should be built around. This gives people a real reason to come uptown. That’s why Harlem Song is so important. It will show what the potential up here really is.”

While every producer will tell you it’s a challenge getting an audience to come to anything, the people behind Harlem Song know that getting people to go above 96th Street is a special challenge. Everything flows from ticket sales, so the producers have identified half a dozen different audiences they are targeting: residents of upper Manhattan (meaning blacks and Latinos); domestic and international tourists; students and college groups; avid theatergoers; eventgoers (families who plan four or five outings a year in the city); and culture seekers (Manhattan opinion leaders and trendsetters).

Harlem Song producer John Schreiber, whose credits include Hard Rock Live on VH1 and, with George Wolfe, Elaine Stritch at Liberty, knew when he began this project that Harlem is the third-most-visited tourist destination in the city. “The problem is the tourists often don’t get off the bus except maybe for church or Sylvia’s.” To change this, Schreiber and his partners have made a deal with Gray Line tours to be a featured attraction, which means the guides will talk up the show. They have also made a deal with a group of eleven nonprofit institutions – including the Studio Museum and the Dance Theatre of Harlem – known as the Harlem Strategic Cultural Collaborative. One dollar from every ticket sold will go to the group, which will cross-promote the show.

They’ve even tried to address the comfort level of potential showgoers who are perhaps a little nervous about going to Harlem. Free parking has been arranged at a garage one block from the theater, and there will be concierge service in the lobby of the Apollo available to arrange car service or dinner reservations.

The hope is that a successful run for Harlem Song will provide the kind of boost that will resuscitate the moribund landmark. Ever since the state took over the shuttered and bankrupt theater in 1992 and leased it back to the nonprofit Apollo Foundation, the woeful history has been one of underperformance, financial impropriety, and flat-out neglect.

Finally, in 1998, the state attorney general stepped in and the mess – which essentially centered on Percy Sutton and the contract held by his company Inner City Broadcasting to produce the syndicated television program It’s Showtime at the Apollo – began to get cleaned up. In the process, Sutton, a close friend of Congressman Charles Rangel’s, was forced to make a million dollars in back payments, and there was a shakeup of the board that oversees the theater, including Rangel’s resignation.

Now Derek Johnson has put together a new team that includes David Rodriguez, an experienced theater manager, and Nicole Bernard, a sharp lawyer and businesswoman who will handle marketing, new business, and promotion of the Apollo as a brand. The first task was fixing up the tattered Harlem icon, which had, essentially, become a dump. Seats were broken and torn, the carpeting was ripped and worn out, the paint was peeling.

The renovation is in its first phase, a $14 million sprucing-up that includes new carpeting, fixing the broken seats (and eventually replacing them), splashing around some fresh paint, bringing the sound and lighting up to current standards, repairing the famed yellow-and-red blade sign, and computerizing the marquee. The $39 million second phase will include restoring neglected architectural details; constructing a new lobby, gift shop, and bathrooms; and redoing the dressing rooms.

But returning the Apollo to anything resembling its glory days will require more than new seats and fresh paint. “We realize that credibility is a huge issue,” says Johnson. “We’re trying to distance ourselves from the theater’s recent history, and the best way for us to accomplish that is to do what we say we’re going to do.”

There are also long-range plans for the Apollo, which involve using the theater as the focal point for a huge performing-arts center that would require taking over several retail spaces immediately to the east as well as the Victoria theater, a movie house that’s been closed for years.

This would include building a larger theater – one of the Apollo’s primary problems is that it doesn’t have enough seats to be economically competitive in today’s entertainment market – more rehearsal space, and perhaps a hotel and jazz museum. Johnson refers to these plans as “aspirational,” but quiet fund-raising has actually been going on for some time.

Throughout the difficulties, the Apollo, or at least the idea of the Apollo, has maintained its luster. “Performers know there is something special about this place,” says Rodriguez. “A couple of times recently, James Brown has pulled up unannounced out front and asked to come in and just play the piano for five minutes. People really want to experience the ghosts here.”

Not everyone agrees that one of the keys to the community’s economic future is a thriving Apollo Theatre. Carl Redding, owner of Amy Ruth’s, the popular soul-food restaurant on 116th Street, is skeptical about trying to attract visitors by turning Harlem into a kind of living museum dedicated to the arts and culture. “The people who come to Amy Ruth’s are primarily people from the community,” says Redding, a lifelong Harlem resident who spent eight years as Al Sharpton’s driver before opening his restaurant three years ago. Partly because of his time with Sharpton, the restaurant attracts celebrities in politics, sports, and entertainment.

“I put no faith and no trust in tourists. And 9/11 proved it. When the tourists stopped coming, places like Sylvia’s suffered,” says Redding. “My business went up during that period, because people in the community were looking for a place to get together and talk and to mourn.”

Redding is an interesting case, because he represents both the old and the new Harlem. He is at once a testament to the opportunities that now exist uptown for the savvy, determined small-business man as well as an example of all those residents who are angry about what they believe is the gentrification of Harlem.

While he dismisses the tourist business (“I used to get angry when I’d see the buses riding through filled with people looking at us like we were monkeys in the zoo”) and ambitious attempts to attract outsiders on the one hand, he applauds the arrival of what he calls triple-A businesses like Starbucks, Pathmark, Disney, and Magic Johnson’s movie theaters on the other. And when he praises these changes, he points out that he knows there will be lots of people who won’t be happy about his comments.

Redding started Amy Ruth’s by getting some of the people he’d met through Sharpton to invest in his idea (Percy Sutton and Johnnie Cochran, to name just two). He didn’t go to the empowerment zone for help. “I had no credit and no financial history, which is usually the problem with black businesses.”

But there was another reason as well. “I’d heard all the bad stuff about them,” he says. “They had a really bad reputation. Everyone said the empowerment zone was only here to re-gentrify Harlem. That they were only giving loans to big businesses coming in from outside the community like Starbucks and Disney and they didn’t care about the small, black businessman.”

Redding is not alone in his ambivalence about the changes uptown. Harlem’s state assemblyman, Keith Wright, who lives with his family in the very same Harlem apartment he grew up in, has similarly conflicting emotions. “Every community wants to see progress and development,” says Wright, “but you have to balance it by making sure the indigenous folks don’t get left out. And right now there are a lot of folks up here who are feeling left out. People are worried about rising housing costs, and I have to say it’s reaching crisis proportions. I’ve been here all my life, and I can’t afford one of these brownstones now which are selling for $700,000 and up.”

In truth, however, with all of the change and development that have taken place, Harlem is light-years away from being gentrified. It is, in every sense, still what politicians and developers euphemistically refer to as an emerging neighborhood. In other words, it remains predominantly a neighborhood of poor people. Much of the investment, particularly the high-profile kind, has taken place on the major commercial strips, including 116th, 125th, and 145th Streets. In between these thoroughfares, there are islands of rehabbed and renovated and newly built residential properties floating in a sea of run-down and abandoned buildings.

Many in the community, like the Reverend Calvin Butts, believe that arts and culture are critical to Harlem’s continued revival, but that affordable middle-class housing is as well. And that means housing for two-income couples making between $60,000 and $100,000 a year, to build a desperately needed middle class in the community. “Phase three,” says New York secretary of state Randy Daniels, “must be home-ownership. Right now it’s only about 6 percent in Harlem. But if we could get it up around the citywide average of 30 percent, that would do more for long-term empowerment of the residents than just about anything else. It gives you a stake, and we’ve got to preach it from the pulpits. It’s an absolutely essential step.”

And with all of the change in how things are done uptown, there are still anachronistic pockets of the old obstructionist political infighting. The empowerment zone, for example, continues to be a kind of rat’s nest of animosity between the governor, Rangel, and the mayor (though perhaps not as bad as when Rudy Giuliani was in office). In seven years, the zone has given out only slightly more than a third of its $300 million. And only three weeks ago, Terry Lane, head of the empowerment zone, announced his resignation.

Insiders say that city and state officials have long been unhappy with Lane. They claim, however, that Rangel protected him. But all that changed when Johnnie Cochran was named to head the zone’s board. He surprised everyone who assumed he’d be just a figurehead by actually attending board meetings and, as one official put it, “looking under the skirts” to find out why the place was such a mess. Cochran challenged Lane’s management, the two men clashed, and Lane’s hand was finally forced. Lane emphatically denies this version of events. He says leaving was his decision and he and Cochran continue to have a good relationship.

Even at the Apollo, some things are more intractable than others. Almost inexplicably, after the financial mess was uncovered by the attorney general’s office in 1998, Sutton’s company was allowed to renew its contract for It’s Showtime at the Apollo.

That agreement has now expired again, and the Apollo is now seeking bids. One of those who want the contract is Frank Mercado-Valdes, founder and CEO of the Heritage Network, a $60 million television-sales-and-syndication company. Mercado-Valdes’s company, now located in the financial district, is set to move to Harlem Center next year. The building, on 125th and Lenox, is on the same corner where Mercado-Valdes once sold T-shirts.

His welcome in Harlem, however, may be a little muted. Mercado-Valdes, a voluble, ambitious salesman, tried to secure the rights to the Apollo show back in 1998 when Sutton was under investigation. Sutton retained the contract, but because of Mercado-Valdes’s bid ended up paying 30 times what he had been paying: The fees for the rights went from $50,000 to $1.6 million.

Mercado-Valdes’s bidding war with Sutton attracted the attention and wrath of his friend Charlie Rangel: “I was turned into a pariah. In fact, I’m still a pariah. I still can’t give my credit card to half the people in Harlem without them looking at the name and saying, ‘Oh, you’re that guy who went after Mr. Sutton.’ When I decided to move my company uptown, I put in a grant application with the empowerment zone. But when I found out Rangel still has a problem with me and the application wouldn’t be approved, I withdrew it.” (Rangel says he wouldn’t know Mercado-Valdes if he bumped into him. However, he says he does remember Mercado-Valdes bidding in 1998.)

Mercado-Valdes started his company ten years ago with a simple idea. He’d read that Ted Turner had purchased the rights to all the old MGM movies to run them on his cable channel. Mercado-Valdes decided to do the same thing with black movies: secure the rights to run them on TV in syndication.

Now his company, which was once called the African Heritage Network, also produces original programming, including a syndicated show called The Source: All-Access, done in conjunction with the hip-hop magazine, and a new fall show being done with Dick Clark called Livin’ Large, which is a kind of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous meets Cribs.

“My feeling about the Apollo deal is that it should be kept in Harlem,” he says. “Let Sutton and his company continue to produce the show, and my company will handle syndication and sales. Why let a syndicator like King World do it? They’re part of Viacom, which just moved BET out of Harlem. But I know Sutton will never go for it. I can’t beat that guy.”

For George C. Wolfe, the idea of creating an original piece about Harlem, a piece that would be a running attraction at the Apollo and a kind of symbol of the community’s continuing vitality, was irresistible.

“I’ve had, for lack of a better word, a very fortunate career downtown. So the idea that I could use my skills and my profile to bring energy to the Harlem community appealed to me on a very fundamental level,” Wolfe says.

A particular challenge within this context would seem to be the past 30 years, those decades when the community was declining and suffering and yielding few if any reasons to celebrate.

“I don’t look at it that way,” Wolfe says. “I think one of the unwritten stories of the history of Harlem, which is the story of every single thriving black community in America, is the consequences of integration.” Wolfe recounts a trip he made with his father ten years ago back to his hometown in Kentucky. “I was riding around with his sister and she was going, ‘Oh, and the ballroom was over there. And that’s where Dr. So-and-so’s office was. And the coffee shop was on that street.’ And she was describing all these black-owned businesses in this little town of Providence, Kentucky, which was completely segregated, so black people had to have all their own things,” he says, narrowing his eyes and leaning forward.

“So a real phenomenon is that from Harlem’s inception as a thriving black community and well into the fifties, it was the only game in town for black people living in wonderful, fabulous places and not being victimized. So what ends up happening is not how the community died, because it didn’t, but how the community was dissipated by the phenomenon of integration and who and what kept the community together. The story throughout Harlem Song is what is the driving collective energy of the day.”

Of course, he also hopes that Harlem Song will contribute to the current collective energy. “I would love this piece to be a source of pride for the community and for it to serve as an economic catalyst,” he says, standing in the doorway now.

“And I’d really love it if Harlem Song could contribute to shattering the idea that Harlem is a separate nation on the island of Manhattan.”