Berliners refer to it as Herkunftsstriptease, or “origin striptease,” which my friend Otto Pohl, an American journalist who moved there six months ago, compares to the “Where did you go to college?” game New Yorkers play when they meet at bars or parties. It’s how young Germans place one another within their country’s history, which is intensely present in the city’s complex and creative leap into the future. What happened to your family during World War II? And during the Cold War? Were you raised under communism or capitalism? Where were you when the wall came down? In the new Berlin, everyone has a story.

If you went to Berlin ten, or five, or even three years ago, you have not seen this Berlin; in fact, whether you’re in a gallery carved out of a former communist housing block or a gleaming “green” office building, it feels as if it were a different city than it was three days ago. And if you thought Germany was somewhere you’d never want to go, it is time to reconsider, as a steadily increasing stream of enlightened New Yorkers has been doing. And Berlin, with its dynamic architecture, its booming arts scene, its infectious, young kineticism, is at the center of this reemergence. It has something, in its bullet-scarred walls and ambitious rebuilding, that resonates for a visiting New Yorker.

I spent ten days in June on a leafy street called the Bleibtreustrasse in a neighborhood called Wilmersdorf. At times, it felt, with its unhurried pedestrians and their little dogs, quite a lot like Paris. The neighborhood is all dappled light: squares fronted by churches, strawberry stands, bakeries, well-stocked drugstores filled with unfamiliar (and therefore alluring) cosmetics. It delivered everything I wanted from a vacation in a European capital – which can be, for someone coming from New York, little more than the chance to walk among a population that is seemingly less harried, less aerobicized, less consumed by career ambitions and Atkins diets.

“It’s such an idealized European city,” says Kym Canter, creative director for J. Mendel, who has vacationed in Berlin twice in the past year. “It’s as beautiful as Paris and London, and as exciting, but there are no crowds, no attitude, and it’s much less expensive.”

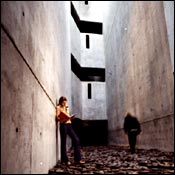

But a trip to Berlin is freighted in a way that your standard castles-and-cobblestones European vacation isn’t. It was, after all, the capital of the Third Reich and the front line of the Cold War. History, unpleasant and very recent, is always unabashedly on display. Here you might notice the ornate entrance to a building from the twenties wrought in sensual Art Nouveau curves, and there you might see a boxy concrete housing block slapped together hastily in the fifties, and you are reminded that within the lifetime of the man walking his dog across the street, people were dragged from their homes on this very same sun-dappled block. There are bullet holes in the walls of apartment buildings, a church whose steeple was blasted by a bomb and never replaced.

“It’s like time travel,” says Anna LeVine, a writer and photographer from New York who moved to Berlin in September 2001. “You can travel from the seventeenth century to the twenty-first in five minutes on the S-Bahn. You can go from Art Nouveau to the GDR, from the Enlightenment to fascism to communism, just by riding on the train.”

My S-Bahn station was at Savignyplatz, which is on a pleasant, quiet corner of Charlottenburg, where there are cafés, small galleries, and endless stores selling schmuck (jewelry) and antiques. Heading east, the train screeches through the Tiergarten, the massive park in the city’s center, and you catch glimpses of Hansaviertel, an experimental development built in 1957 to accommodate the postwar housing crisis. Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen, and Oskar Niemeyer all contributed buildings (there are 36 in total) with ambitions to reinvent urban life as grassy and sociable. A shady path snakes through it all.

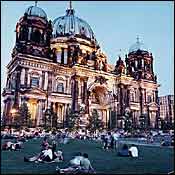

Farther on, there is the Potsdamer Platz, which is Berlin’s current architectural work in progress. Fifteen years ago, this was a no-man’s-land, the front on which the world’s superpowers played an outsize game of chicken, a bit of pavement you could be shot for walking across. There is still a gaggle of cranes, but now some buildings are completed, and in the mornings, a busy workforce files into glassy, mirrored towers, including the Daimler-Benz building by Renzo Piano, with a glass-louver system that allows for energy efficiency and the flooding of natural light. Around the corner in the lobby of a bank on the Pariser Platz, there is a walk-through sculpture by Frank Gehry. While so much of Europe has the feeling of a museum, Berlin feels like a museum in the making, a fabulous, Blade Runner–style pastiche of Gothic relics and soaring steel and glass.

And now, flash, you are in East Berlin, so easy, so close. “The physical wall has been entirely removed,” says Pohl, “but if you look around just a little bit, you know immediately which part you’re in.” Much of the prewar architecture is the same, if considerably more worn. The communist architectural achievements of East Germany are vastly different. The Karl Marx Allee, for example, resembles nothing so much as a Stalinist Moscow boulevard, with its rows of massive, solidly symmetrical buildings. The luminaries of the GDR (Katarina Witt, for example) lived behind these thick-paned windows, and the ground floors were taken up with state-run supermarkets selling none of the goods the residents saw advertised, via a simple antenna, on their televisions and radios. Some of these storefronts have been converted into bars with recessed lighting that serve mojitos and play electronica.

One of the rawest extant views into the GDR is the Stasi Museum, housed in the former headquarters of the Stasi, the secret police. “They just left it exactly as it was in 1989, and you can see, in retrospect, that things had really been crumbling for a long time,” says David Kurnick, a Columbia graduate student who visited last spring. “It was depressing and fascinating. It was sixties décor from the height of the Cold War – they were clearly strapped.”

There are renovations in East Berlin, but it feels mostly rundown, the type of rundown that often serves as a backdrop for creative energy. Here café clientele is pierced, tattooed, dreadlocked. “Berlin has always had the leftist, peace-loving types,” explains Pohl, “because it was this island, and if you lived in Berlin, you were exempted from the draft. So it was filled with draft dodgers. And it was heavily subsidized, because West Germany was always afraid that it was going to die, so there were real incentives for living in Berlin.”

This liberal community is thriving. Parts of Berlin (Kreuzberg, Prenzlauer Berg) are the Williamsburg and Greenpoint not only of Germany but of Europe: young artists in the streets in platform sneakers, thrift shop after thrift shop. The Schönhauser Strasse is filled with the types of boutiques and galleries you might expect to find on the Lower East Side or on Bedford Avenue. It helps that rents are lower than in other European cities, and beer and cabs and nightclub covers are cheaper as well.

“It’s an interesting place for artists because they can afford living from their art,” says Klaus Biesenbach, the artistic director of Kunst-Werke (KW) and chief curator at P.S.1. “There are lots of free spaces, mentally and geographically.” Biesenbach’s KW is a studio space, artists’ residence (designer Hedi Slimane has an apartment there), and gallery on Auguststrasse. Its opening created a burst of galleries on the same street – including the popular Eigen + Art – but these days, galleries are sprinkled throughout the city.

“Galleries keep moving around Berlin,” explains Aura Rosenberg, a New Yorker who spends part of every year at the KW with her husband, artist John Miller. Rosenberg’s family fled Germany in the thirties, so it is particularly meaningful for her to be back, and she recently completed a book, Berlin Childhood, in which she retraces the steps of Walter Benjamin, who lived his own childhood in the city before he, too, was forced to flee.

It is disconcertingly easy to travel, by S-Bahn, from this modern economic center to a concentration camp called Sachsenhausen. “It was one of the first camps, and taking the train, you can really feel how close this was to the city. If you were a deportee, that’s the route you would have taken,” says Kurnick, who made the trip in March. “And the camp is just at the end of a little street. Nineteen is a little house, 20 is a little house, and No. 21 is a concentration camp. If you look one way down the street, it’s an East German suburb; if you look the other way, it’s a concentration camp.”

It is absolutely disturbing. And, at the same time, rather inspiring to see how far a city can come. “Berlin has reinvented itself so many times. So many terrible things have happened there, and now the city has taken what was a no-man’s-land and every major architect is building there,” says LeVine, whose move to Berlin occurred a few short days after September 11. “The Germans have a way of incorporating history, both good and bad, and living with so many layers simultaneously. There’s no rubble in Berlin, and that for me was really impressive, seeing that this city has survived and reinvented itself. It has a real tenacity.”

More on Berlin