Ronald Perelman was born on New Year’s Day, 1943, and celebrates the occasion in extreme style. His annual New Year’s Eve–birthday party in St. Barts is one of the world’s most exclusive social events. The billionaire takeover artist hosts the gathering on Ultima III, his multi-million-dollar, 188-foot yacht, which he keeps docked in Gustavia harbor. In past years, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, and Jerry Bruckheimer have attended the event, and for Perelman’s 60th, Barry Manilow sang “Happy Birthday.” This year, Russell and Kimora Lee Simmons, Owen Wilson, and Usher were among the 200 guests.

The highlight of the evening is, naturally, the countdown to New Year’s. Shortly before midnight, the guests gather on the observation deck of the boat. A cake is typically waiting, with the candles lit. When the big moment arrives—“three … two … one …”—the people in the crowd shout “Happy New Year!” Then, in chorus, they sing “Happy Birthday” to Perelman. A canopy of fireworks explodes against the nighttime Caribbean sky.

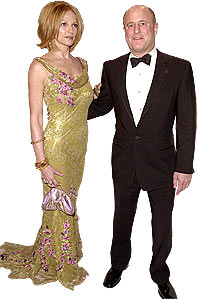

The scene feels magical, in an over-the-top mogul-fest sort of way. Or at least it has in years past. This year was different. Something was plainly wrong. Ellen Barkin, the feisty, flop-mouthed actress and Perelman’s wife of five years, was not at Perelman’s side at midnight. Later, she would tell friends she was trying to stay as far away from him as possible. The night before, she had told them, she and Perelman had had a particularly brutal fight, their worst ever.

Perelman and Barkin had always been an unlikely and combustible pair. Cynics said that he married her because he wanted a Hollywood trophy wife with a marquee name and that she married him because she wanted his money (Perelman’s net worth at the time was estimated at about $3.3 billion; it’s now valued at $6.1 billion). The couple’s romantic histories, doubters noted, didn’t foretell a lasting union: Perelman was divorced three times; his last breakup was an ugly and highly public split from the doe-eyed Democratic fund-raiser Patricia Duff. Barkin was divorced from actor Gabriel Byrne and, when their relationship had fallen apart, she took to dating the much younger actor David Arquette (he was 23; she was 40). Still, friends say that Perelman and Barkin, at least for a time, were truly in love. As different as they were outwardly—he the pit-bull corporate raider and Upper East Sider, she the downtown boho actress—they had a fierce attraction, friends say. Their relationship drew energy from their differences. “We never bore each other,” Barkin once said.

Barkin also liked Perelman’s charm, generosity, and impulsiveness, a friend of Barkin’s says. He sent her a gold Cartier watch on her birthday after knowing her only two weeks, the friend says; his marriage proposal followed just two weeks after that. Perelman, in turn, seemed to like Barkin’s salty, frank demeanor. They also had great physical chemistry. “They couldn’t keep their hands off each other,” one of her friends says. “A very physical relationship,” one of his friends says. They fought, but they had always worked things out. “High highs and low lows,” says a friend of Barkin’s. In the end, their dramas had always ended happily.

But not this New Year’s Eve. Tonight, Perelman and Barkin weren’t speaking, a friend of Barkin’s says. They hadn’t been intimate for months, and Barkin speculated Perelman might be cheating on her, the friend says, although Barkin had no evidence. As the clock approached midnight, hundreds of revelers in linen shirts and party dresses had gathered on the docks, as they do each year, to watch the fireworks and toast in the New Year. On the Ultima III, the guests soon stood waiting in place for the big birthday moment. Perelman’s cake was ready, the candles flickering. But Barkin was elsewhere, on the top deck with a friend, not at Perelman’s side.

“The tension,” one observer says, “was thick.”Back in New York the next week, people close to Barkin say, Barkin was still raw from the fight they’d had on the boat. Even so, she never thought that weeks later, she’d be served with divorce papers and booted from her home.

Divorces are intensely personal and often contentious affairs. Spouses fight. Anger grows. Accusations are traded back and forth. It can be impossible to know with certainty what goes on inside a marriage, or what causes one to end (divorce agreements are confidential, and people loyal to ex-husbands and ex-wives invariably color events in the ways that reflect best on their family members and friends). But when two such well-known figures as Ron Perelman and Ellen Barkin divorce, the relationship inevitably becomes a matter of public discussion. The news that Perelman and Barkin were splitting up was first reported in January in the New York Post. According to gossip columnist Liz Smith and reporter Phil Messing, Perelman’s motivation for divorce was financial. If Perelman didn’t seek a divorce soon, the Post reported, a clause in their prenuptial agreement stated that Barkin would be entitled to a significant increase in alimony.

Perelman and Barkin declined multiple requests to comment for this story, citing the confidentiality of their divorce agreement. Interviews with friends and associates, however, begin to give definition to their tempestuous relationship. What emerges is the portrait of a marriage in which both parties started out in love, but finally split up when their fundamental differences and mutual hardheadedness—the very things that attracted them to one another in the first place—created too much friction to sustain.

Ellen Barkin never had much interest in meeting a Ronald Perelman. Not at first. Suits with cigars? Not her type. She grew up in the outer boroughs—first in the Bronx, then Queens—with her older brother, George. Her father was a salesman for Fuller Brush and also worked as an usher at Yankee Stadium. Her mother, Evelyn, was an administrative assistant at Jamaica Hospital. From an early age, Ellen was rebellious. As a teenager, she wanted to go to Woodstock, but her parents refused. In protest, she stayed up one night dropping acid. She hung out in the Village and, at 15, auditioned at the prestigious High School of Performing Arts on a lark. She was accepted, but when she got there, her teachers didn’t have high hopes for her. “She’s just not pretty enough,” she remembered a teacher telling her parents in one interview. “She has a little talent but no spark.” She went on to Hunter College, paying her way by waitressing in punky clubs and no-frill restaurants. An acting career seemed far-fetched. Barkin once recalled in an interview that she was so emotionally unstable in her early twenties she didn’t bother lining up auditions. “I couldn’t even turn the lights on,” she once said. “I was so depressed. I used to just sit in my dark apartment.”

Perelman’s roots were all country club and business. He grew up in a conservative home in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, a Jewish suburb north of Philadelphia (Perelman is a modern Orthodox Jew who is known to speak with his rabbi once a day and is said to travel with him). His father, Raymond, a factory owner and deal-maker, would dress up young Ronald in a blazer and tie and have him sit in on his board meetings. The pressure turned Ronald into an angry and conflicted child, overly mature, distant, and “a loner,” according to Christopher Byron’s book Testosterone Inc.: Tales of CEOs Gone Wild.

Perelman went to Wharton, as an undergraduate (like his father) and then for his M.B.A. As a student, he made a reputation for himself as a financial prodigy by pulling off a million-dollar deal for his father. At 21, on a summer cruise to Israel, Perelman met a shy 17-year-old named Faith Golding. Her grandfather was the wealthy real-estate mogul who built the Essex House on Central Park South. After marrying and finishing grad school, Perelman went to work for his father and started a family. He and Golding would have four children. Perelman was busy—and restless. After failing to convince his father to retire and let him run the business, Ronald and his family moved to New York to begin a new life.

To start his empire, Perelman borrowed $1.7 million from his wife to buy a stake in a jewelry chain, Cohen-Hatfield Industries. Then, with the help of junk-bond guru Michael Milken (another Wharton alum), Perelman went on a borrow-and-buy tear. Surrounding himself with a team of aggressive and loyal attorneys, he took control of companies including MacAndrews & Forbes (originally dealing in licorice extracts, it’s now Perelman’s holding company), Technicolor (a film-processing company), Pantry Pride (a supermarket chain), and Consolidated Cigar (which custom-produced a long, skinny H. Uppman for Perelman, hand-rolled from its factory in the Dominican Republic).

As his business prospered, Perelman was rarely home. Then one day in the winter of 1982, Faith Golding received a mysterious bill for a gold bracelet from Bulgari, according to Richard Hack’s unauthorized biography When Money Is King. Suspecting an affair, Golding hired a team of private eyes to follow her husband. They reported back that Perelman was having an affair with Susan Kasen, an Upper East Side florist; during the subsequent divorce proceedings, Golding also claimed that her husband had charged at least $100,000 on gifts and lavish trysts to the company she had loaned him the money to buy. In a hard-fought settlement, Golding would ultimately win $8 million in alimony, reportedly the least amount received by any of Perelman’s four wives.

In 1982, Barkin made her first feature-film appearance in Barry Levinson’s Diner. She got rave reviews, then continued to impress critics in a variety of film and theater roles with her quirky looks and tough, sensual demeanor. In a Times review of the Off Broadway play Eden’s Court in 1985, Frank Rich summarized her performance this way: “If it were really possible to give the kiss of life to a corpse, the actress Ellen Barkin would be the one to do it.” After major roles in The Big Easy, with Dennis Quaid, in 1987, and Sea of Love, with Al Pacino, in 1989, Ellen Barkin the not-pretty-enough teenager and depressed New York waitress had become Ellen Barkin the unusual Hollywood sex goddess.

She was also in love. During the making of Siesta, in 1987, Barkin fell for her co-star, Gabriel Byrne. When they first met on the set, Byrne told her she had the most beautiful set of eyes in the world.

“Thanks,” Barkin said with typical bluntness. “They’re contacts.”

Born in Dublin, Byrne was one of six children, and before acting, he had worked as an archaeologist, a cook, and a matador in Spain. Barkin remained the bad boy in the relationship. “[Byrne] has an innocence and honesty I don’t have,” she once said. They married on a whim in Las Vegas. “I think if we’d planned it for three months, one of us would’ve backed out,” she recalled. “He’d also never been married, and he was 38. So someone would’ve not made it to the wedding, for sure.” Their marriage lasted five years and produced two children. Their split was amicable. Some gossip writers refer to it as the friendliest divorce in Hollywood.

Moving on from his somewhat less tidy divorce, Perelman met his second wife, Claudia Cohen, the New York Post gossip columnist turned entertainment-television reporter, over lunch at Le Cirque, a restaurant he dined at so often he began calling it his “cafeteria.”

Perelman and Cohen seemed a perfect fit: She provided him entrée into exclusive social circles, and as a couple, they created society news by constantly renovating their homes and making extreme demands on their contractors. One observer quoted in When Money Was King assessed the couple this way: “They were loved in public, scorned in private, and lived this fairy-tale life.”

The fairy tale produced another Perelman child, and perhaps Perelman’s greatest conquest, Revlon, which he purchased using $1.8 billion in junk bonds. The deal was considered one of the nastiest takeovers in corporate history.

In 1992, Perelman met Patricia Duff, then married to Michael Medavoy, the chairman of TriStar Pictures, over dinner at Taillevent, in Paris. Perelman was there with Cohen on vacation and had scheduled dinner with their friends Don Johnson and Melanie Griffith, both of whom did ads for Revlon. Unexpectedly on that trip, Griffith and Johnson ran into Duff and Medavoy, and all agreed to have dinner together, and Perelman was bewitched by Duff.

“This is a man who will take care of you and everyone you know and love forever, whether he has $100 or $100 billion,” Barkin once said of Perelman.

By 1994, Perelman was divorcing Cohen, and later courted Duff. His persistence paid off, and Duff moved to New York to be with him. But the marriage would unravel shortly thereafter, and after eighteen months, the couple filed for divorce. What ensued was one of the most high-profile, costly, and vitriolic breakups in memory, during which Perelman allegedly told Duff, “I will destroy you, and I will enjoy it.”

Duff reportedly claimed, among other things, that a bitter argument had broken out over a prenuptial agreement Perelman had proposed. She went into labor with their daughter, Caleigh, a month early, and Perelman’s lawyers presented her with the document while she was in the hospital, she said. Under the proposed prenup, she said, he offered $1,131,744 a year in payments, maintenance, and jewelry, along with a Connecticut mansion in the event of divorce. She wouldn’t sign. In fact, she was so incensed that she skipped their wedding ceremony planned at Perelman’s rabbi’s house (they ultimately reached a compromise and were married in a civil ceremony). In the divorce case, Duff also claimed that Perelman had obsessively courted her, trailing her uninvited on a trip to Hawaii, and breaking in on a private therapy session in Los Angeles (Perelman said he was invited on the Hawaii trip, and denied the therapist claim). Duff also claimed Perelman had a volcanic temper. In one of their fights, she said, Perelman erupted after she missed a lunch with him on a ski vacation in Aspen, and threw her toiletries against a wall. A court-appointed therapist recommended that Perelman receive therapy to control his temper. The total settlement in their eventual separation was estimated at $30 million.

Duff spent $5.2 million on legal fees, but ultimately lost custody of Caleigh (she did get extensive visitation rights). “On balance,” the judge ruled, “the father is better able to prioritize Caleigh’s interests and promote her well-being.”

If Perelman won the custody battle, though, he lost the public-relations war. At one point, Perelman claimed in court that Caleigh would do fine on a food allowance of $3 a day—he later told the Times he regretted the statement, but didn’t deny it. He was branded by a tabloid as “the meanest dad in America.”

On Oscar night 1999, Ronald Perelman met Ellen Barkin. At the Vanity Fair after-party, he approached her. She remembered his pickup line this way: “So, are you married, or single, or what?”

A few days later, Perelman called his reliable friend Melanie Griffith and asked for Barkin’s number. In his relentless style, Perelman began leaving messages on Barkin’s answering machine. Reluctantly, she agreed to meet him and found herself charmed by his old-fashioned romanticism.

Barkin knew about Perelman’s intensity, his tendency to be controlling, and his ugly past divorces, her friends say. But she had her own legendary temper, and in one interview she said she believed her fuse was quicker to light than his. “I finally met my match,” she said about Perelman. “In business, Ronald is tough; you don’t put over anything on him. But personally, he’s very gentle with women. In fact, in terms of compromise, I give him more credit than I do myself. He has enormous patience with me. I yell at him, but he never does, even though I sometimes think I’d be yelling at me.”

As a nascent couple, Perelman and Barkin had a charged, give-and-take dynamic. Julianne Moore, the actress and Barkin’s best friend, once told a story that seems to capture Barkin and Perelman’s chemistry. “We were sitting around the pool in East Hampton, and invariably there’s a lot of kids, and a lot people get thrown in the pool. Ronald rushed Ellen to sort of shove her into the pool, but Ellen being Ellen, they pushed and pulled and tugged. He finally sent her in, but she pulled him in with her. I thought it was an incredible metaphor for their relationship. They’re really evenly matched.”

Early on, Perelman made clear his feelings about how Barkin should conduct her movie career, her friends say: no sex scenes, no kissing scenes, no movies shot on locations away from New York. And all scripts must be personally approved by him (a Perelman friend says Perelman encouraged Barkin’s film career, and didn’t suggest any limits).

At that point in Barkin’s life, acting wasn’t a top priority for her. Her kids were getting older. She wasn’t being offered the most interesting parts, and was tired of taking bad ones that she felt she had to just for the money. She was also supporting her mother, Evelyn, and her brother, George, a former editor at National Lampoon and High Times, was living in her New York apartment and working on screenplays. Besides, Barkin was hardly a workhorse by nature. “I wish I had a little more ambition,” she once said. “But then what would I do? Turn down more roles with more vehemence?” She once playfully confessed, “Me no likey worky.”

Perelman offered relief from all that. He demanded to be allowed to install her mother in a fabulous New York apartment blocks away from their townhouse. Ellen and Evelyn protested that the rent was too high; Evelyn worried that if Ron and Ellen’s relationship soured, she wouldn’t be able to afford it herself. But Perelman was insistent, Barkin’s friends say. When asked in one interview what she most liked about her husband, Barkin said, “He’s a real caretaker. And it just extends forever—this is a man who will take care of you and everyone you know and love forever, whether he has $100 or $100 billion.”

Barkin herself was wowed by Perelman’s life of extreme luxury. He maintained huge homes in New York, Florida, and the Hamptons, constantly jetting among them. Barkin was also spellbound by the art hanging on his walls. “Are you joking me?” she once recalled saying to him. “I can sit for hours in the library or in the living room and look at the Picassos, the Matisses, the Lichtensteins, the Mirós, the de Koonings, the Rothkos.”

If Barkin seemed overwhelmed by it all, she also enjoyed it. And she seemed to enjoy him. Cindy Adams, the New York Post gossip columnist, remembers meeting the couple for the first time at her home for a shivah call—her husband had just died—and they arrived looking like a matching set, both wearing white button-down shirts and blue jeans. As Barkin approached her, Adams says, she noticed a string of pearls around Barkin’s neck.

“Aren’t they gorgeous?” Barkin said. “They’re the first pearls I’ve ever had.”

The wedding in June 2000 was small, some 45 guests or so. But beneath the festive veneer, there was stress. That very day, Duff was testifying that Perelman had waited to tell Caleigh he was marrying Barkin until the day before, and that when he finally had, Caleigh was distraught.

Perelman and Barkin’s prenup was another issue. In the months leading up to the wedding, Barkin had told a friend, she and her lawyers had raised concerns about certain clauses of the agreement (a Perelman friend denies Barkin raised such concerns). Barkin signed the contract the day before the wedding. “I would never use the word naïve with Ellen Barkin in the same line,” one of her friends says. “But she really loved him. She had heard all the other stories about his other wives. She thought this one would be different somehow.”

In many respects, the marriage worked. She loosened him up and turned the townhouse into more of a home, persuading him to lay off half his uniformed staff of armed security guards, waiters, butlers, and chefs. “I don’t want to walk downstairs at midnight to get a bag of potato chips and find two people in my kitchen,” she once said. “If you need tea,” she said of her husband’s wishes, “I’ll get it for you.” She expanded the kitchen (which was said to be small because Perelman ate virtually every meal out) and made it kosher. Before she moved in, the townhouse was decorated in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russian furniture, but Barkin didn’t like the Russian-baron look, she said in one interview. With Perelman’s blessing, she converted the house into something lighter, airier: French modern.

“It was easy,” Barkin once said of her interior-decorating gig. “I had $8 billion to spend.”

In the Duff custody case, which continued to linger in the first months of Perelman and Barkin’s marriage, Barkin went to bat for her husband, testifying in 2000 that Ronald was a good father. “He’s always patient, never scolding,” she testified, and she said that he drove Caleigh to school on the days when she was with him. “He wakes her each morning and tucks her into bed each night, after Hebrew prayers, with her stuffed bunny, Hoppy.”

“The whole story here is that Ron Perelman couldn’t recognize what he had to lose. Finally, he had someone who loved him and his family, someone he couldn’t buy with all the money in the world.”

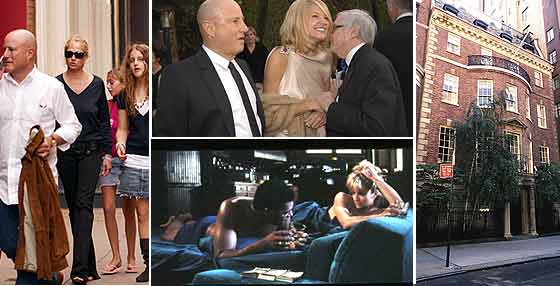

For Barkin, the toughest part of dealing with Perelman was his jealousy. In April 2005, on Late Night With Conan O’Brien, Barkin told the story about a time she and Perelman were watching television in bed and came across a scene from a movie she did—several years before she married Perelman—with Laurence Fishburne, an espionage thriller called Bad Company. She told him to change the channel.

“Oh, no, honey,” she recalled saying. “Click! Click! You don’t want to watch this!”

But Perelman didn’t change the channel. “Yeah, yeah,” she remembered him saying. “I want to watch this!”

Though there is no nudity, Barkin straddles Fishburne on a dock and has a shrieking orgasm. Perelman didn’t seem to appreciate the artistry. “I’m not speaking to you!” he said, to her recollection, and didn’t talk to her for two weeks. Perelman tried to palm off the incident like a joke at the time. He said, through a spokeswoman, “I think my wife has a terrific sense of humor.”Although Barkin enjoyed the fruits of Perelman’s wealth, she felt suffocated by it as well. In interviews she did to promote her movies, Barkin complained about his maids’ ironing her son’s T-shirts and said that his kitchen was so big she could never find the spatula or the olive oil she liked to use. The spatula and olive oil were virtually useless anyway, she once said, because Perelman would consider it a “compromise” if they had one cook instead of three. She suggested that all the square footage and butlers made her uncomfortable. She said once, “Sometimes we talk about buying a little apartment, like a normal apartment, where we’d go on weekends, and I’d have my own kitchen, and I could cook. ”

Barkin also took roles in more movies: Spike Lee’s She Hate Me (2004) and Palindromes (2004), a Todd Solondz film. Barkin was so eager to take the part in Palindromes that she accepted it without even looking at the script.

Barkin believed that her work caused friction. “This is not a smooth-sailing relationship,” Barkin once said. “Ronald doesn’t do this for a living. It’s one thing if you say to your actor-husband, ‘I’m going to go to Tunisia for three months with George Clooney, and we’re going to do a love story—come visit me! And by the way, I’m taking your whole family with me, and see ya.’ But try saying that to a businessman, and he’ll look at you like you’re from Mars.”

The first time they split up was when Barkin was offered a role in Ocean’s Twelve, in the spring of 2004, says a friend of Barkin’s. Perelman was opposed because filming was in Chicago, Barkin’s friend says. Barkin went anyway, and when she came back, tensions between the couple were so high that she and her kids went to stay at Soho House, the friend says. Barkin, says the friend, considered asking Perelman for a divorce, but they ultimately patched things up by going to a marriage counselor recommended to them by Claudia Cohen. To Barkin, the issue was control. “Ronald’s not used to a wife who has taken care of herself since she was 18, so it’s a struggle—occasionally hilarious,” she once said. “The other day, he said, ‘The problem is you want to be me.’ I laughed and said, ‘I am you. We’re not in your office; we’re in the house, and I am the boss.’ ”

After the new year’s trip to St. Barts, Barkin and Perelman were still not on speaking terms, her friends say. Instead of flying back with him to New York on his Gulfstream, she and members of her family flew home separately. Inside his townhouse, they kept their distance. They had fought throughout the marriage, Barkin told friends. She figured they’d eventually work things out; maybe they’d go see the marriage counselor again, like they had the last time they almost broke up. Only a month before, Perelman had given her a $1.5 million ring over dinner at Nobu, a friend of Barkin’s says. But about a week and a half after St. Barts, Perelman told her he wanted a divorce.

On January 20, news of their divorce became public, and Perelman sought to refute claims that the impetus for the split was financial. A friend of his says that he felt Barkin was too tough to please and he could no longer make her happy. “She’s a brutal killer,” another Perelman friend says. “She’s tough as shit.”

A Barkin friend has another theory: “The whole story here is that Ron Perelman couldn’t recognize what he had to lose. Finally, he had someone who loved him and his family, someone he couldn’t buy with all the money in the world, and in the end it came down to what it all always comes down to with him: money and control.”

A Perelman security guard, who has worked for him for more than ten years, offers this view: “They both seemed miserable. He didn’t seem to have a good time with anything he did.” With Barkin, it was the same, the guard says. “They deserved each other.”

Perelman and Barkin and their lawyers haggled over the final-settlement terms. A Perelman friend with knowledge of the agreement claims Barkin was entitled to $3 million per year in alimony if they divorced. A friend of Barkin’s familiar with the deal puts that number at $2 million. Also in dispute is a clause that allowed Barkin to receive $5 million to purchase a home. Perelman doubled that fee to $10 million as a sign of good faith and generosity, the Perelman friend says. The Barkin friend acknowledges the doubling of the fee but says it was done only after Barkin surrendered her share of an asset they both owned, worth about $5 million. In all, the Perelman friend claims Perelman gave Barkin some $60 million in the divorce settlement, including about $35 million in what they call “convertible assets,” meaning the lavish gifts he gave her during their marriage. A Barkin friend claims Perelman is trying to inflate the size of the settlement by including those gifts in the $60 million figure, and insists Barkin received “not one penny more” than $20 million.

“This wasn’t such a bad deal for both of them,” says Adams, the Post gossip columnist. “He got a Hollywood name, and she got a lot of great jewelry and cash in the bank. For five years, it was a great investment. You don’t necessarily marry a Ronald Perelman for his looks. He’s not Kevin Costner, you know.” To understand their breakup, she says, you have to understand Perelman’s track record with women. “He tires easily,” she says. “First he married into the Jewish money, then he married the Jewish princess and got to know the New York money contingent, then he met the Hollywood people through Patricia Duff. Ellen was really a continuation of that. Now, if he marries again, it will have to be European royalty,” she says. “Then he would have had one of everything.”

Moving out was a debacle. Armed guards had watched Barkin pack her things. On February 9, wearing white sport socks, jeans, and a shaggy wool robe, Barkin stepped out of their townhouse and lashed out at a Post photographer, allegedly saying, “If you don’t get the fuck out of my face, I am going to kick you so hard in the balls you won’t know what hit you!” Some days earlier, Perelman had cut off rent to her mother’s apartment, friends of Barkin say. On Valentine’s Day, a judge finalized their divorce (it’s not clear how the couple divorced so quickly).

On a recent Friday afternoon, outside her Chelsea office, Barkin appeared rattled as she left the building and made her way down 27th Street. Dressed in worn black jeans and sunglasses, she refused to talk about the breakup, except to say that she felt that Perelman’s public-relations machine was trying to spin the story his way. “It’s like oil and water,” she said. The truth will “rise to the top.”

In the month or so since the divorce, Perelman has announced several major business deals, including the $750 million acquisition of the film-processing firm Deluxe films. A friend of Perelman’s says he’s not dating (“He just got divorced; give him time to heal”), but “Page Six” has linked him to a former hedge-fund marketing executive named Rachel Rosen, who is said to resemble a young Ellen Barkin, and to former model turned magazine editor Kelly Killoren Bensimon, whom “Page Six” dubbed “younger and hotter” than Barkin.

For the next phase of her Hollywood career, Barkin is trying to produce her first film, The Easter Parade, a remake of one of her favorite books, the 1976 Richard Yates novel of the same name. The story is about two sisters. It spans some 40 years and starts with the following line: “Neither of the Grimes sisters would have a happy life, and looking back it always seemed the trouble began with their parents’ divorce.”

• The Billionaire and the Bombshell

Perelman vs. Barkin: Scenes from a broken marriage.

• What Perelman’s Ex’s Cost

• The Prenup Epidemic

• How to Ask for a Prenup

• What to Do When Asked