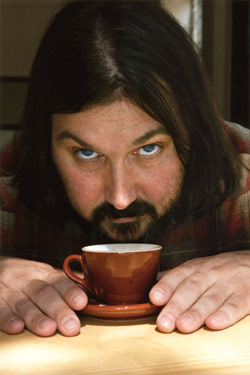

Duane Sorenson is six foot two. He wears Chuck Taylors, has a beer belly and an unruly brown beard, and ends many sentences with “fuck.” The 37-year-old founder of Stumptown, the Portland, Oregon–based coffee company, is hard to ignore, partly because of his physique but more because of his bordering-on-obnoxious insistence that he knows, better than anyone, just how coffee should taste. With his business, Sorenson has begun to create a coffee connoisseurship far beyond the big green chain and its venti lattes. At Stumptown, you don’t have a cup of coffee; you have a Finca El Injerto, Pacamara (that’s the farm from which the beans were sourced and the varietal from which they descended). Sorenson once paid $130 per pound for Geisha, a bean varietal from Panama known for its complex flavor profile and its rarity. “It tasted like perfume,” he says.

Enough of the Pacific Northwest believes in Sorenson’s message (which includes fair trade, of course) that he now has five cafés, two café-roasteries, and one stand-alone roastery in the region. But when you’re a believer, you want to spread the message, preferably to the largest and most visible market. So eleven months ago, Sorenson loaded up a U-Haul and drove to Brooklyn. He found an apartment in Carroll Gardens and began laying the groundwork for converting New York from its generally tragic coffee habits. “This town is ridiculous,” he says. “Make a good cup of coffee for your neighbor, fuck!”

Sorenson has now built a roastery in Red Hook with a tentative opening date of May 15. He’s opened Café Pedlar in Cobble Hill with the owners of Frankies Spuntino. And the first New York Stumptown café is set for this summer in the lobby of the new, very groovy Ace Hotel (also a West Coast transplant) at 29th Street and Broadway.

Given Sorenson’s fervor, it’s tempting to make more of the fact that he grew up in a Pentecostal family in Puyallup, Washington, about an hour south of Seattle, the cradle of modern coffee culture. Sorenson’s father was a sausage-maker and meat-curer who encouraged his son’s interest in foods and flavors, spices, and textures. In junior high, Sorenson got a job in a local coffee shop and got hooked on the beverage’s smells and tastes. As his palate developed, he began to organize events like a seven-course food-and-coffee-pairing dinner with a local chef. In college, Sorenson continued working in cafés and started buying and roasting his own beans. Eventually, he got fed up. “They were price-sensitive,” he says of his last employer. “They wanted to buy okay coffee for cheap. So I said, ‘Fuck you, I’m starting my own company.’ ”

In 1994, Sorenson married his grade-school sweetheart. They had $8,000 saved to buy a house; Sorenson used it instead to buy his first roaster, a 1919 German-made Probat. He got a job at a beer shop by day; by night, he worked on opening his first café. His boss loaned him the money for his first espresso machine. He opened in November 1999 and, for the first year and a half, lived off tips and bartered coffee for meals while pursuing his dual goals of sublime coffee and fair trade. Within six years, Sorenson had five Stumptowns in Portland. In 2007, he expanded into his home state, opening two cafés and a roastery there. But his personal life was unraveling; he was traveling around the globe two weeks out of every month to develop partnerships with farmers, leaving his wife to handle their two small children on her own. “I think it’s hard, because of how much I’m invested in Stumptown,” he says. They divorced two years ago.

Sorenson now shares a three-bedroom apartment with two of his employees, Jules Manoogian and Lizz Hudson. Their kitchen counter is a veritable café: a dozen French presses, an espresso machine, three or four hot-water kettles, one grinder, a couple of Thermoses, a Melitta coffee brewer, and heaps of brown-bagged Stumptown beans. This is Stumptown’s local headquarters, where Sorenson cups (coffee lingo for tasting) new batches and plots how to bring New Yorkers into the fold while listening to jazz, punk rock, and African music (on vinyl, of course).

It’s an increasingly competitive universe, to say the least. The small percentage of the population that cares enough to buy artisanal coffee is already being chased. Never mind Starbucks and its 264 franchises in New York; there’s Ninth Street Espresso, Grey Dog, City Girl, Irving Farm, Abraço, and so on. Roasters like Chicago’s Intelligentsia and Counter Culture from Durham, North Carolina, are a few years ahead of Stumptown in indoctrinating New Yorkers on the subtleties of bean varieties and breaking the psychological price barrier (a pound of beans from one of those roasteries can be as much as $27). Sorenson responds by confidently spouting his mantra: Stumptown offers the best of the best. “I’m not saying it to be arrogant,” he says. “I’m saying it because it’s a true fucking story.”

Coffee quality can be objectively measured, to a point. There are professionals who evaluate a coffee just as one would a wine. They study the flavor profile; the cleaner and sweeter it is, the higher it will rank on a 100-point scale. Top specialty roasters buy coffees rated 85 or above, but once you’re that high in the rankings, how much of what you’re tasting is real and how much perception? Sarah Allen, the editor of Barista magazine, says that a top roaster like Stumptown goes to such extraordinary lengths to find the perfect coffee that it becomes personal. “It’s like when you think to yourself that your child is special in a way no other child is,” she says. “That’s how people like Duane feel about their coffee.”

Which means, of course, that he won’t let just anybody buy his beans. Sorenson approaches potential clients like he’s on a blind date, and he’s not afraid to say “sorry.” “I don’t want to sell my coffee to everyone,” he says. “It’s not for everyone. I don’t have the fucking time for it, man.” The Chelsea café Tbsp qualified for Stumptown earlier this year; its owner Melissa Chmelar had called Sorenson after drinking Stumptown at another café and realizing “I felt like I was cheating. This is like a religion.”

All would-be vendors attend mandatory barista training as well as a three-hour class that includes a PowerPoint presentation and a video about El Injerto, one of the Guatemalan coffee farms Stumptown works with. Hudson likes to point out a shot of an El Injerto picker bent beneath a 150-pound sack of coffee berries. “That’s what I think about when people ask for a free refill,” she says.

Since Stumptown’s move to the city, twenty accounts have signed on, including Milk Bar, Marlow and Sons, and Frankies Spuntino. The food blogs are paying close attention to the roaster’s infiltration; some have even mapped cafés, color-coding them depending on their specific roastery allegiance. Sorenson’s rapid expansion has produced at least one defector. When Ninth Street Espresso, Stumptown’s first and highest-profile partner in New York, switched to Intelligentsia beans last month, it caused a small uproar. Ninth Street’s owner, Kenneth Nye, says bloggers made too much of it; he simply wanted to get back to proprietary blending, which Stumptown doesn’t offer. “Some shop owners take comfort knowing that there are a dozen shops using the same product,” says Nye. “We never did. For us, it was a very weird transition to have a coffee that was available so readily in so many places.” Sorenson sees things differently. “I wouldn’t let him put a sticker over the Stumptown bag,” he says. “That’s our coffee, man.”

• How It Gets From the Farm to the Cup

• A Taste Test Against New York’s Reigning Roasts

• Interactive Map: Where to Find It