The first time Keith McNally ate in a restaurant, he was 17 years old. He was living with his dockworker father, his mother, and two brothers and a sister in a small prefab home, built as temporary housing in London’s crime-ridden, working-class, post-Blitz East End. At his job as a bellhop at the London Hilton, he had been discovered by a film producer and cast in a movie, The Life and Times of Charles Dickens, with Michael Redgrave. That movie led to other roles, including playing a schoolboy in the West End in Alan Bennett’s first play, Forty Years On, starring John Gielgud. It was with Bennett that McNally found himself one evening at Bianchi’s restaurant in Soho. He ordered melon and steak, the only words he could make out on the all-Italian menu. “I was intimidated, also fascinated,” he says.

His parents didn’t share their son’s new enthusiasms. One evening, just as a television play in which he had the lead role was about to start, his parents changed the channel. “They didn’t want to watch it,” McNally remembers. “It’s almost inconceivable. But actually, I quite liked that, because I was embarrassed.” When he told them he was to appear in the play with Gielgud, “My mum burst into tears: ‘You’re going to be working with a homosexual.’ ”

When Bennett wrote his next play, Getting On, one of the characters was inspired by McNally. “It was a rather lost character. I saw him as somebody who’d slipped through the net of the educational system, and whose talents were never going to be called upon, and whose life was going to be wasted,” Bennett says. “I was quite wrong, of course.”

McNally arrived in New York in 1975, intending to pursue a career as a director. Instead, a series of jobs waiting tables at places like Maxwell’s Plum and Serendipity led him to One Fifth, in Greenwich Village, where he ascended from oyster shucker to general manager. Saturday Night Live, then in the first flush of its Not Ready for Prime Time Players heyday, held its after-parties at the restaurant. McNally began developing a loyal coterie of customers and friends, including fellow immigrants Lorne Michaels and Anna Wintour. When he opened his own restaurant, the Odeon, with brother Brian and future wife Lynn Wagenknecht, the fashionable crowd from One Fifth followed them to Tribeca.

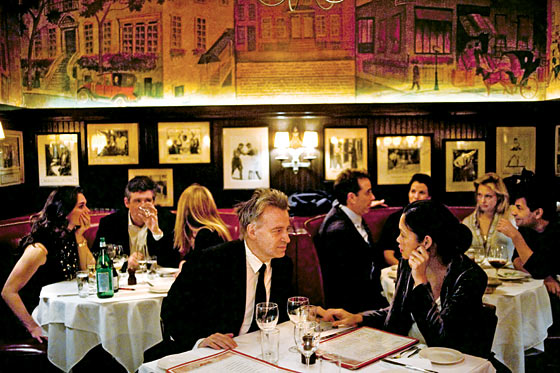

A truism about McNally’s restaurants is that they are like stage sets, with a theatrical sense of lighting, of casting, of narrative, of scale and movement and mise-en-scène. Meticulously engineered to feel like found objects excavated from a golden past that never was, his places are augmented-reality versions of the bistro, the brasserie, the trattoria, the café, the tavern. The Odeon introduced McNally’s vintage, salvage-based design sensibility and the then-novel combination of good food in a casual atmosphere. From the moment it opened, in 1980, the Odeon became the downtown nexus of post–Studio 54 early-eighties glamour. Janice Dickinson, the model, recalled a night when she strapped on a saddle and John Belushi rode her around the restaurant. It was at the Odeon that Jay McInerney would despoil his nose with Bolivian Marching Powder en route to writing Bright Lights, Big City.

McNally’s feel for the next neighborhood has been uncanny, and the tally of places he opened in underserved neighborhoods, just before they exploded, is a history of Manhattan’s gentrification in the last three decades: After the Odeon in Tribeca, there was Cafe Luxembourg in a deserted part of the Upper West Side (1983), Nell’s on West 14th Street (1986), Lucky Strike in West Soho (1989), Pravda in Nolita (1996), Balthazar in East Soho (1997), Pastis in the meatpacking district (1999), Schiller’s on the Lower East Side (2003). If his two latest, Morandi (2007) and Minetta Tavern (2009), both in the West Village, weren’t homesteading in quite the same way, Pulino’s Bar & Pizzeria, which opens next week at the corner of Bowery and Houston, marks a return to form.

Among the city’s leading restaurateurs, almost no one but McNally and Danny Meyer has built an empire that, as Times former food critic Frank Bruni says, “combine[s] the restaurant equivalent of big box office with serious foodie followings.” But if the St. Louis–bred Meyer is a genial, Jimmy Stewart–voiced executive in coat and tie who’s serving haute cuisine at Eleven Madison Park and franchising his fast-food stand Shake Shack as far away as Kuwait, McNally is the sensitive, temperamental, bed-headed artist in khakis and an old sweater, who has rebuffed opportunities to cash in by replicating any of his restaurants, who dropped out of the business for a few years to write and direct movies, and who routinely goes over budget in thrall to some private aesthetic compulsion.

When Keith Mcnally is getting ready to open a new restaurant, he ritually professes that it will be his last. Six weeks before Pulino’s, his newest last restaurant, is to open, McNally, who is 58, is hurrying along the sidewalk on and Bowery, hair boyishly askew, wearing an unbuttoned, speckled tweed overcoat and an army-green cloth backpack. McNally spends a lot of time walking around, and his restaurants invariably start with a space he has seen. This spot he’s had his eye on for five years.

It’s a classic McNally project. On a corner, in a commercial, slightly gritty neighborhood, Pulino’s remixes a number of favored McNally design elements—checkerboard floor, chicken-wire glass, pressed-tin ceiling, bottle-lined walls, antique mirrors—with droll touches of Bowery Vernacular, including a couple of tables made out of blue police barricades stenciled don’t cross the line. Brick archways frame an open kitchen with two wood-fired ovens, where chef Nate Appleman, of The Next Iron Chef and San Francisco’s A16, will turn out thin, crispy, Romanesque pizzas and other wood-fired dishes.

McNally borrows a tape measure and checks the diameter of a table: 36 inches. He asks a workman to sit in the booth. “Is that the right size table for you?” McNally asks, in his North London accent. It’s a snug fit for four diners, but McNally thinks that could be a good thing. “If you’re with a very attractive woman, and she’s getting close to you, would you be upset?” he teases. McNally is constantly soliciting whoever’s nearby to tell him what they think. “He asks for a lot of opinions,” says Riad Nasr, co-chef at several of McNally’s restaurants, “but I think he knows the answers to most of them.”

McNally heads downstairs to the bathrooms, where, in a cheeky touch, a cloudy window separates the men’s and women’s bathrooms. He thinks the glass should be more transparent, and Kate Pulino, an art-history-trained McNally staffer who unwittingly gave her boss the name for his new restaurant, suggests a different type they can try. “If there was a woman in there,” McNally says, turning to another worker in the men’s room, “and she was really attractive, and she wanted to see you completely naked—I’m not saying this is ever going to happen … ” McNally walks from the men’s side to the women’s side, appearing as a dark, blurry form through the glass. “I don’t think I’ll be using the bathroom.”

McNally is restlessly attentive to the minutiae of his empire. “It’s a business that involves fretting all the time,” says hotelier André Balazs, “and he does it constantly and thoroughly and without respite.” When Millard (Mickey) Drexler, the CEO of J.Crew and a Balthazar breakfast regular, was having coffee uptown one day and saw a grubby Balthazar Bakery truck drive past, he shot McNally an e-mail. “I remembered that he hates when his trucks are dirty,” Drexler says. McNally was grateful, and distressed (reminded of the incident months later, he knits his brow and seems momentarily re-traumatized).

In the ramp-up to opening, Pulino’s has owned much of his attention. When its brick walls, during construction, got dust on them, McNally loved the look and had workers do three weeks of tests to figure out how to achieve it permanently. In his office, he has been experimenting, with a cup of black Balthazar coffee and a bottle of Syrah-Grenache, to turn the marble for the pizza counter just the right shade of sepia. Blank CDs were stacked behind him; over the next month, he would choose a thousand songs to play at Pulino’s, broken down by time of day.

McNally first thought of opening a pizzeria nearly five years ago, after developing an interest in the corner space at Bowery and Houston. He thought that a restaurant in that location should reflect its environment, a bustling crossroads, and pizza was in keeping with that spirit. It took him three years to secure the space, and construction has lasted another year and a half years. As high-end pizzerias like Co., Motorino, and Veloce swept the city in the intervening years, McNally has quietly gnashed his teeth. “I know it looks like I’m jumping on the bandwagon. But in the end, it doesn’t matter. What matters is whether it’s good.”

In July, two weeks after Nate Appleman moved to New York without a job, a headhunter called him, and two days later he found himself meeting McNally at Balthazar. They talked for three hours, hit it off, and McNally offered him the Pulino’s job on the spot. Because of Appleman’s interest in meat, a room slated for wine storage was reassigned as a dedicated butchering room, and the Pulino’s menu has broadened. “When we were fleshing out the idea,” Appleman says, “I went to him and said, ‘Aren’t you worried this is the same as Morandi?’ He said, ‘Not at all. This is based on wood-fired cooking.’ ”

McNally lives in the expectation of failure. “Basically, I’m pessimistic, but I think it’s Russian roulette,” McNally is saying. It’s a recent Wednesday afternoon at Balthazar, and he’s sitting on a banquette next to the raw bar. He picks at a plate of seviche and glances twitchily around the room. Pulino’s is McNally’s eleventh restaurant opening, but he insists that it has been the most challenging yet. It’s the first restaurant where he has hired a name chef, and his most expensive project to date. It was supposed to open in December. With six weeks to go before the new opening date in March, the project is running low on money, and in three days he’ll fly to England, to tell his backer in Pulino’s, Richard Caring, the owner of clubs and restaurants including the Ivy and Soho House, that they need to jointly inject about 30 percent more cash than envisioned. “I’m always in this position of being overbudget and behind schedule,” McNally says.

So far, it has always worked out. McNally’s various businesses gross a total of about $70 million a year, and they net profits ranging from 8 to 14 percent. But he doesn’t have confidence that his streak will continue. “You know at one point you’re going to have a big failure,” he says. “Most of my big failures have been reserved for my private life. But for the restaurants, I’m waiting for something. I tend to think that if you get good reviews for one restaurant, the next one generally doesn’t. And so I’m worried actually about this place, because Minetta was quite well received. So I’m preparing myself for the worst.”

As lunch winds down, he seems almost melancholy. “I think everything hangs by a thread, whether it’s a relationship or one’s business or one’s health.” He is absently tearing his napkin into pieces and rolling them into little balls. “That’s the way it is, and I think it’s not a bad thing to think that, and then maybe deal with it. The thing where you say, ‘Oh, I never thought they could break up, I never thought they would divorce’? Everything, everything hangs by a thread.”

A few hours later, after stopping by his office to interview people for busboy, waiter, and bartender positions at Pulino’s, McNally walks from Soho to the West Village for a meeting at Morandi with all his general managers. With seven current restaurants and some 1,100 employees, McNally spends most of his time, when not launching a new place, just keeping the whole enterprise running.

Huddled around a table next to the bar, his G.M.’s take turns reporting on the past week’s operations: The first weekend of brunch at Minetta went better than expected; a server at Schiller’s has developed an attitude problem; Pastis is getting ready to debut a revised menu and to re-stain its floors. The issues brought to McNally’s attention extend to the astoundingly picayune: Morandi’s G.M. reports buying two extra $35 bicycle helmets because one delivery guy was bothered by another delivery guy’s fancy helmet.

As always, there are customer issues. Kelly Cutrone, the fashion publicist and subject of the Bravo reality series Kell on Earth, has recently had a string of outbursts at Balthazar and Lucky Strike. “This is the same woman I called a few months ago?” McNally asks. “I always liked her.”

“She’s having a hard time because of this whole TV show,” the Lucky Strike G.M. says.

“Well, it’s not our fault,” McNally says. “I don’t want her to be abusive to staff.”

It is agreed that the Lucky Strike G.M. will talk to her.

Another regular, the head of an ad agency, has canceled seven of fifteen reservations he’s made at Minetta; at Balthazar, he’s simply been a no-show on several occasions and been difficult when he has shown up. “Anyone who cancels that regularly, in a place where it’s so difficult to get a reservation,” McNally says, “then we should not waste time with them.”

“I’m sorry,” the Balthazar G.M. says, “he’s notoriously horrible. The other day, as the waitress is pouring the wine, he’s like, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.’ ”

“I hate that sort of thing,” McNally says, “and I don’t want staff to be subjected to it. Let’s take him away from double A. Make him single A. He’s trouble. In fact, that guy, no more Minetta.”

Cultivating, rewarding, and occasionally punishing regulars is an integral piece of McNally’s formula. Since opening Balthazar, he has had a private reservation number for them, staffed by a live person fourteen hours a day, and ranked them from A to AAA, in order to assign priority to reservation requests. Only about fifteen people are AAA, Anna Wintour among them. (“Minetta doesn’t deliver,” McNally says, “but we deliver to Anna.”)

With regulars and friends, McNally is incredibly generous. Oliver Sacks, the neurologist and writer, has known McNally since the mid-seventies, when McNally sought out Sacks to treat a kitchen burn. A few months ago, McNally ran into Sacks, who had recently undergone two orthopedic surgeries, at the pool at Chelsea Piers. “I had lost nearly 40 pounds and was so weak and in pain that I had to be slung into the pool by a special device,” Sacks says. “Keith looked at my gaunt figure and said, ‘I’m going to put some meat on you.’ He said, ‘You’re going to have dinner for the next month on my account, from Pastis and Morandi.’ I put on fifteen pounds with that delicious food. I almost feel he did a lifesaving thing for me.”

At the G.M. meeting, when it’s the reservations manager’s turn to speak, she mentions a few VIP bookings. Naomi Watts is hosting a party at Minetta that Sunday. And reservations has just received a call asking for a table for eight, for Tori Spelling, at Minetta, that night.

“Who’s Tori Spelling?” McNally asks. “I have no idea.”

“Aaron Spelling’s daughter,” someone says.

McNally stares blankly.

“90210,” adds Josh, the Schiller’s G.M. “It was a show in the nineties.”

Although McNally is passionate about theater and film, he doesn’t watch television. While he is savvy enough to want celebrities as part of his customer mix, and he is alerted whenever a VIP is dining in one of his restaurants (on a typical Wednesday evening at Minetta, Harold Ford Jr. was at the bar, Malcolm Gladwell and Brian Grazer were dining with two young women, and Ben Stiller sat in a corner booth), he doesn’t actively seek them out. McNally attracts this crowd partly through inertia: The group of loyal customers he cultivated when he managed the restaurant One Fifth has followed him ever since. It helped that this downtown group—people like Michaels and Wintour and Julian Schnabel—just happened to be of a generation that was on the verge of making New York its own. McNally grew up alongside them and knew how to take care of them. They became a kind of perpetual promotion machine for his restaurants. “He has a very good sense of what people enjoy when they hang out,” says Mike Nichols, the director.

McNally doesn’t socialize with fellow restaurateurs and is allergic to anything he deems self-serious, such as Danny Meyer’s book Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business. “I would rather be shipped off to Iraq than write or read a book like that,” McNally says. Later, he elaborates in an e-mail: “As a restaurateur there’s no better operator in the country. However, there’s categorically no sillier or more pretentious title for a book. I’m just relieved Dostoyevsky didn’t use the same title for Crime and Punishment.”

Still, McNally’s role as proprietor of the city’s most fashionable restaurants has resulted in relationships, of varying superficiality, with a lot of famous people. Meg Ryan has come to his house on Martha’s Vineyard for breakfast, and several years ago, McNally and his wife, Alina, spent a weekend in Dublin with Balthazar regular Bono, because he wanted McNally to renovate a restaurant Bono owns there. (“He was very kind and generous, but I didn’t want the job.”) When McNally and Alina were married, in 2002, Keith Richards and Julian Schnabel were among the guests, though Richards was there only because he happened to have rented McNally’s house on Martha’s Vineyard, and McNally doesn’t remember why Schnabel was invited. (“It’s just very difficult because it’s exclusively about him in the conversation,” McNally says of Schnabel.)

“Of course, I’m a little bit impressed with certain people,” he says, “but not that much. I probably do a good job at concealing it.”

McNally’s father wasn’t as practiced at projecting nonchalance. When he was 82 years old, he came to live with Keith and Alina in their new house in the West Village, and he stayed busy folding napkins and packing up delivery orders at Balthazar until he died of stomach cancer, in December 2008. “He would sometimes be too pleased to have met someone who was English and famous and the sort of person he would never have been in a position to talk to in London,” says McNally. “That would irritate me.”

“My brother and I had class issues,” says Brian McNally on the phone from Vietnam, where the restaurateur behind Indochine, Canal Bar, 150 Wooster, and 44 has been living for the last three years. (Keith and Brian have had long periods of estrangement, but at present they e-mail every day.) “How can you not? We don’t bang on about it, but there was a class system that really excluded you and defines you in a way. Orwell said the English people are ‘branded on the tongue’ … I think for Keith’s restaurant career it’s been a tremendous advantage, because he’s never been seduced by that life, because of not ever really feeling a part of it.”

Despite his early successes, McNally itched to do something more meaningful. “I always felt that what I was doing was of no consequence,” he says, “as it probably isn’t, and that I could do without restaurants and the restaurant business. I didn’t have any sense of achievement.”

In the late eighties, he set out to make movies. His first, End of the Night, about a man whose life unravels while his wife is pregnant, was chosen as one of twenty films shown at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes. In 1989, he moved to Paris with his family (he and Lynn Wagenknecht by that point had a son, Harry, and two daughters, Sophie and Isabelle) and wrote and directed another art-house movie, Far From Berlin, starring Armin-Mueller Stahl. He also wrote and sold a third script, Fidelity. But today he’s self-conscious about the movies, which he hasn’t watched in more than fifteen years.

“I thought there was some higher calling, something more important, about making films,” McNally says, “and that I would feel better about myself if I made a film. Maybe I was disillusioned. Very little makes me feel better about myself, that’s what I realized.”

While McNally was in Germany making the second film, his marriage to Wagenknecht fell apart. With three children, and intertwined business interests, the couple’s divorce was especially taxing. McNally ended up selling the Odeon, Luxembourg, and Nell’s to Wagenknecht, keeping only Lucky Strike. With the money he got from selling the restaurants, he bought four acres on Martha’s Vineyard, and spent the next year renovating the house on the property. “It was kind of therapeutic, because it was really some form of reconstruction of my inner life after being very quite devastated by divorce.”

Losing his restaurants made McNally appreciate them finally. “I never, ever before thought the Odeon was such a good place,” he says. “And when I went back in for the first time, six months after my divorce, I thought how lucky the person must have been to have owned this place.”

In 1996, for the first time in seven years, he opened a new place, Pravda, a Russian Constructivist–inspired bar in a Nolita basement, with investments from friends including Lorne Michaels and Ian Schrager. It’s the only project Schrager has ever invested in that wasn’t his own. “Keith is really one of the two people in this business, in the entire world, that I most respect,” Schrager says (the other is Jean-Louis Costes, in Paris). Pravda showed that McNally could still attract the old crowd. But it was the following year that he would open what would arguably be his biggest hit: Balthazar, with its soaring ceilings, neck-craning celebrity population, and peerless frites. McNally followed Balthazar with two more successes, Pastis and Schiller’s Liquor Bar.

In an exceptionally fickle industry, McNally’s places have shown a remarkable ability to age gracefully, evolving from restaurants-of-the-minute into enduring standards. Of the ten places he has opened in the last 30 years, nine are still around (Nell’s, his only club, is the one McNally-sired place that ever closed, and it lasted an improbable eighteen years). “He’s never really fallen into the celebrity trap,” says Anna Wintour. “Ralph Lauren has always said this to me, that you can’t be too hot or too cold, and I think Keith comes from that same sensibility. He realizes that the caravan can pass on, if it becomes too much the place to go, and that you have to keep—and I don’t mean to say this in a derogatory way at all, but—the real people happy at the same time, because they’re the ones that are going to keep coming back.”

McNally tries to build his restaurants, he says, in such a way that he can look at them, five years after they open, and know that he’d build them in exactly the same way if he had to do it over again. Not that there haven’t been missteps. “I cringe at the word ‘design,’ ” he says. “There are certain things in my restaurants that are overdesigned. Not many, I think, but there are some that I’m very embarrassed by. But I’m not going to say what they are.”

Although many have swooned over McNally’s transporting, letter-perfect re-creations of the bistro and brasserie, some critics have at times found his restaurants to cross the line from knowing, loving reproduction into the realm of pastiche, simulacrum, and cliché. Morandi, his first Italian restaurant, was also the first of his places to draw almost uniformly critical reviews (including from this magazine’s Adam Platt). In the restaurant’s decorative fiascoes of Chianti and greatest-hits menu (fritto misto, vitello tonnato), the Times’ Bruni saw “Italy as theme park” and asked: “Is this tribute or burlesque?” McNally reacted by reading every review Bruni had ever written—some 150, at that point—doing a statistical analysis of Bruni’s treatment of female chefs, and penning an open letter positing that sexism might play a role in his criticism. (Morandi’s then-chef was a woman.) “I lost a lot of respect for Keith McNally when he did that,” Bruni says. “For a restaurateur to brand the critic a sexist or a misogynist seems like a very small-minded, out-of-bounds way to strike back.”

“I think I was grabbing at straws, probably,” McNally says now, a bit sheepishly. “I probably felt aggrieved. I’m now almost embarrassed. I should have just accepted it and moved on.”

“You’re a very good girl, aren’t you?” McNally is saying. “But why do I like you?”

Five-year-old Alice is on his lap, burying her face in his polo shirt.

“I don’t know,” she says.

“Would I know that in my head or my heart?” her father says.

“I don’t know,” Alice says.

“Or my leg? Do you think it’s my toes that I should check on? They might be able to give me the answer.”

On a Sunday afternoon last month, McNally is at home on West 11th Street. He is just back from his trip to London, where he saw Alan Bennett’s new play, The Habit of Art, ate at the River Café (“so good”), caught an Arsenal match with Richard Caring—and then got together with him again, to eat at Caring’s new Dean Street Dining Room and see the play Enron, but failed both times to mention the reason for his visit: the need for both of them to put more money into Pulino’s. “I didn’t have the guts to tell him,” McNally says. “So now I’m going to write to him tomorrow.”

It’s a warm, cozy, overstuffed house, with a fire going, stacks of books, and a jumble of prewar German Expressionist paintings on the walls. The open kitchen, with a wood oven, deep white sink, and long farm table, is vaguely Provençal and, less vaguely, McNallyesque. The 1841 townhouse, which McNally and Alina gut-renovated before moving in, contains several design elements familiar from his restaurants, including faux-aged plaster, wainscoting, wide-plank pine floors, and subway tile.

The aesthetic is more instinctual than calculated. The places he builds are the places he’d want to go to himself. Much of it comes down to a sensitive Everyman nerve that happens to be attuned to what New Yorkers want. “You have to provide the conditions, although it’s impossible to define what they are, to make it easier to engage with someone,” he says, “to talk, and almost to lose yourself.”

I ask McNally how important authenticity is to him in building his restaurants. “It’s my idea of authenticity,” he says.

McNally is curiously prone to going on ascetic benders. After his stint as a child actor, he spent a year on the hippie trail—traveling through Israel, Afghanistan, Iran, Nepal, and India—in order to purify himself. He opened Schiller’s, he has said, to “cleanse” himself after flirting with a lucrative offer from Steve Wynn to open a Balthazar in Las Vegas.

In 2008, Richard Caring offered to buy all of McNally’s restaurants for $100 million. They eventually struck a deal instead for Caring to invest in Pulino’s. McNally could be getting more than he has bargained for with this partnership. McNally’s sole backer in most of his restaurants has been Dick Robinson, the CEO of Harry Potter publisher Scholastic, who has no hospitality-business ambitions of his own. His co-investors in Minetta are its two chefs, Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson. Caring, on the other hand, is all about taking established restaurants and rolling them out as global “brands.” He sees his investment in Pulino’s as a first step toward deeper involvement with McNally. “We can help Keith on the West Coast, in Middle America, in Chicago,” Caring says, suggesting that a Pulino’s London would be a no-brainer and that expansion is McNally’s destiny. “I think he’d be bored to death growing vegetables in Martha’s Vineyard.”

“All those matters will be decided by me, ultimately, not Richard,” McNally says. And as it happens, he is quite happy growing vegetables on the Vineyard. He has transformed his property there into a farm with pigs, sheep, and ducks, and chicks that he rears in his West Village basement. He spends much of the summer tending a large vegetable garden, nurturing his compost pile, and coddling his pigs (until he roasts them). He reads extensively about sustainable agriculture and this year is planning to buy goats. “I’d like to make goat’s cheese, almost full-time,” McNally says.

“Keith is really passionate about this,” says Vineyard neighbor and multigeneration sheep farmer Clarissa Allen of his agricultural pursuits. “He doesn’t dabble. He was into this before it got trendy.”

Still, even with hoe in hand, McNally, who says he feels “phony most of the time,” isn’t entirely at ease with his gentleman-farmer ambitions. “I feel it’s a bit of an act, to be honest. I hope it’s not, but I do feel that. I know that I enjoy telling people I farm, and I think that’s a bad sign to begin with. Of course, it’s best if people find out that I farm.”

See Also

• Map: The New Bowery Restaurant Row

• What to Eat at Pulino’s