“We are going through an unprecedented building boom right now,” says Rick Evans, an architecture historian and the founder of the San Francisco Architecture Walking Tour. “It’s like the second gold rush is happening in the city, and it’s all driven by tech dollars.”

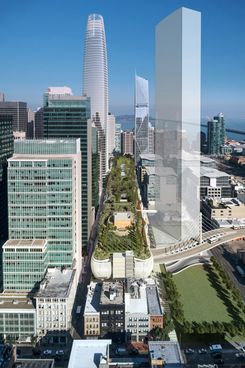

The most exciting development is centered in the South of Market (SoMA) district — also known as the Rincon District — where an urban plan that’s been in the works since 2009 is finally maturing, anchored by a soon-to-be-completed transportation terminal and an urban park. But this is only the tip of the architectural iceberg, says Evans. In the next decade, development in downtown San Francisco will continue to expand, to the dismay of many. “We’re experiencing, maybe for the first time, a real urban revival,” says Evans. “The skyline is changing more dramatically now than ever in history.”

To get you up to speed, Evans took us on a tour of the city’s wacky architectural past and its ambitious, Salesforce-dominated future.

1910: Heineman Building

130 Bush St.

“This is a fun one. Built on a lot that’s 20 feet wide and 80 feet deep, it’s the narrowest building in San Francisco. It’s very skinny and, with a building on either side, it looks like an accordion squeezed, with very beautiful gothic ornamentation. It was built to be a clothing factory and the owner wanted it to reflect what they manufactured: belts, ties, and suspenders. Today, it’s a commercial building, though it’s so dark inside that it’s not very leasable.”

1914: Hobart Building

582-592 Market St.

“This was built by Willis Polk, our city’s most famous architect, but people don’t really understand it. When it went up in 1914, it was the second-tallest structure in the city. In 1970, they took away the building next to it, leaving a blank wall — which is still there today. It looks like it has been cut in half. But it’s a gorgeous building, very baroque and Gothic-looking. Terra cotta — clay that was poured into a mold, fired in an oven, and then placed in steel frames — was used [for the exterior] because it was cheaper than stone and also fireproof. But what’s most important is the aesthetic: When light hits it, it turns different colors throughout the day.”

1917: Hallidie Building

130 Sutter St.

“This is probably the most important building in San Francisco. Located in the heart of the Financial District, the Hallidie is a steel-framed building with a ‘curtain wall’: Projected three feet from the core hangs a wall of glass. [It was built] by Polk in 1917 — a time when everything else on the block was brick and stone. He was giving the city a vision of the future. But at the same time, he was uncomfortable leaving it just glass, so he decorated the building with ornamentation that makes it look like a Victorian window. Now, when people walk by the building, they say: Is that an old building looking new or a new building looking old? It’s landmark-protected, and today is home to the San Francisco location of the American Institute of Architects.”

1959: One Bush Plaza

1 Bush St.

“I always have fun with this one, because when I first show it to people, they’re like, ‘Really? We’re going to talk about this?’ It’s a modernist building, basically a glass box. But after I give my explanation and have them see the building from different angles, they come away saying it was one of their favorites on the tour. In 1959, the Crown Zellerbach paper company built it as their home office. Today about 15 different companies operate in it. What people love about classic buildings built in the ’20s or ’30s is all the detail — the beautiful sculpture and the carved marble and the molding. The modernists also believed in detail, but details that require you to get closer. So, for example, the elevator tower on the outside of the building is covered in 6 million pieces of half-inch tile — imported Italian mosaics. When the sun hits it, it turns a multiplicity of colors.”

1972: The Transamerica Pyramid

600 Montgomery St.

“The Transamerica Pyramid is now accepted as iconic and branded to the city, but when it was built in 1972, it was despised. People actually picketed the site to try to stop it from being built, because it was so different than anything they’d seen. What I love is that the pyramid broke through the conventional, blocky style of architecture [of the time]. The purpose behind the shape is to let sunlight reach the streets more quickly than, let’s say, a square building that blocks light. Think of Manhattan, where you have tall rectangular buildings on both sides of the street — the street becomes like a dark canyon. [With the pyramid], you have light beaming between the buildings.”

2009: One Rincon

425 1st St.

“The city’s new urban plan started in 2009. We took a neighborhood that used to be a high-crime warehouse district, South of Market, or SoMA, and rezoned it for high-rises. It’s basically the new urban center of San Francisco. The master plan included the Transbay Transit Center, a [forthcoming] transit hub that will rival Grand Central Terminal in New York. And One Rincon was the first tall tower in the district. People really resented it. They gave it all sorts of tag names, like the Radio Shack Air Purifier. People still despise it, but I think they don’t notice it as much because it’s overwhelmed by other towers. On the top is something very interesting: a 50,000-gallon water tank. Its purpose is seismic control — it acts as a weight to the building. If the building rocks or shakes, the water sloshes to give counterbalance to the base. It’s the first residential tower in the country with that prototype. When I share that with people, they start appreciating the building a bit more.”

2010: The Millennium Tower

301 Mission St.

“The Millennium Tower, our leaning, sinking tower. It’s not a building that you’d be like, Oh, what is that? There’s nothing distinctive about it — it’s a traditional glass condo box we see everywhere. But it has become a tourist attraction. The issue is that its base is only driven 80 feet [into the ground]. The whole Rincon District is on land that used to be the Bay. So every tower is supposed to be driven into bedrock. Salesforce is about 300 feet to bedrock, and 181 Fremont is 400 feet to bedrock. The Millennium is 80 feet to soft sand. On top of that, it’s the only tower in the district that is concrete-framed, which makes it heavier. The homeowners were the ones who first noticed [the problem]. There are YouTube videos of them placing marbles on the floor so you can see it tilting. There are a lot of fingers being pointed at different entities: the owner of the building; the Transbay authorities that dug the hole for the transit hub, unsettling the land; the building inspectors from the city that signed off on it. The homeowners have a class-action lawsuit against all those entities. As of today, there’s no concrete decision on what they’re going to do or how it’s going to be resolved. But everybody on my tour will ask, ‘Are we going to see the sinking tower of San Francisco?’”

January 2018: Salesforce Tower

415 Mission St.

“[The architecture boom] is led by one tech company: Salesforce. In January they completed their building, which is the tallest in the Bay Area. It’s an obelisk with rounded glass corners that gives it a very sleek look. The intention of the architect, César Pelli, who has done several towers like this, was to give it a timeless look. The main impact is yet to come: a new art installation by Jim Campbell with thousands of LED lights on the top that will project animations. The CEO of Salesforce is giving one floor over to local nonprofits at no charge, but there has still been pushback — a lot of people find the tower overwhelming and say it doesn’t fit into San Francisco’s skyline. But it makes a statement. In the future, when you think of San Francisco, you’re going to think Salesforce.”

Summer 2018: Salesforce Park

130-164 1st St.

“The centerpoint [of the new development] will be a 5.4-acre, elevated urban park — our answer to the High Line in New York. I love the High Line but that’s more of a walkway, and this will be an urban park with an amphitheater and public art and water fountains and botanical gardens. What happens in many cities is that we build these [business] districts, but there’s no life in the evenings or on weekends. So San Francisco’s goal is to make this very open to the public. The park, restaurants, and retail spaces will drive people to this previously underutilized neighborhood. My prediction is that, going forward, when people come to San Francisco for the first time, this will be one of the first places they visit.”

Late 2018: 181 Fremont

181 Fremont St.

“This new tower, right next to Salesforce, is one of the most distinctive buildings in the area. It’s mixed-use, meaning the top of the building is all residential and the bottom is commercial. It’s divided by an open terrace where homeowners and commercial employees will be able to lounge and look at the Bay. [The tower] really stands out: It’s all glass and shaped like a trapezoid, with a spire on top and bracing on it, kind of like the Hancock building in Chicago. The bracing is for seismic control, but it’s also decorative. 181 Fremont is advertising itself as the tallest residential building on the West Coast; and supposedly, one of their top penthouses will be listed at $42 million, making it the most expensive condo on the West Coast. The commercial leasing of the building is one of the largest deals made in the city for decades: It will be the new San Francisco home of Facebook.”

2021: Oceanwide Center

“One of the most exciting things that’s happening right next to [the Transbay terminal] is a new development that’s taking over an entire block. A Chinese investment firm called Oceanwide bought the block and they’re putting in two new towers that will have retail, restaurants, public spaces, and the district’s first high-end hotel. The towers will be built by Foster + Partners, the high-end, modernist architectural firm from London that just completed the new Apple Park headquarters in Cupertino. Oceanwide Center speaks to the broader shift locally: For decades, San Francisco has resisted high-rises and ‘Manhattanizing’ the city — the new development is evidence that the resistance is over. The high-rise movement has won and there is no turning back.”