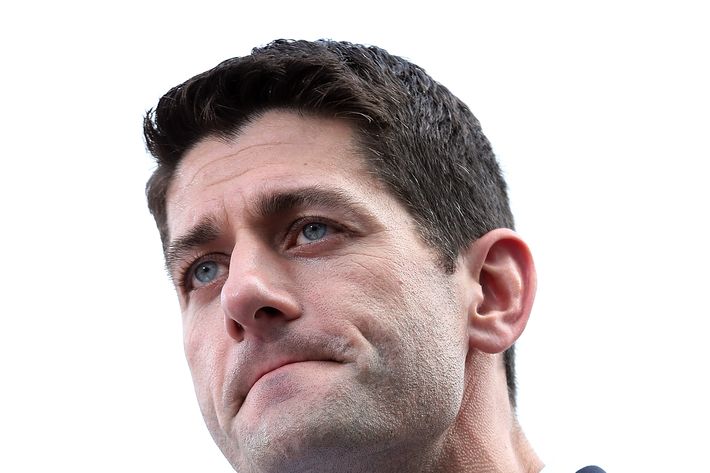

The most impressive thing about Paul Ryan’s political career is how successfully he has evaded any interrogation of his motives. Reporters are a famously cynical lot, prone to analyzing politicians’ words or deeds as maneuvers for self-advancement. Yet Ryan has carried off a brilliantly rapid ascent to power and influence within his party while being paradoxically described along the way as lacking political ambition. His intentions are forever pure. When reporters trailed Hillary Clinton’s “listening tour” of New York, they described it as an attempt to defuse the charge of carpetbagging, disregarding the possibility that she had developed a strong and genuine interest in agricultural life upstate. Even the cosseted John McCain had trouble persuading the media that his disavowal of his immigration bill, when running for president in 2008, represented a heartfelt response to his tour of the border, as opposed to a campaign ploy.

No such suspicion has haunted Ryan as he has embarked on a tour of poor, urban America. Ryan’s behavior certainly fits his political interest — the GOP’s empathy gap, its growing demographic handicap, and the disastrous 47 percent tape all obviously highlight a dire need for Ryan to position himself as a heartfelt champion of poor black America. This is not to say he does not believe in the role he is playing. What’s striking, rather, is how successfully he has persuaded the media not merely to accept his self-definition but to go farther, lashing out accusatorily at the suggestion Ryan is not quite on the level.

McKay Coppins has a long report on Ryan’s journey of repositioning or heartfelt conversion, depending on your level of credulity. Coppins, like all reporters allowed access to Ryan, takes the latter interpretation. (This is the price of admission readers have to pay for Coppins’s inside reporting.) Coppins presents criticism of Ryan as “rabid,”a “caricature,” and “personal,” and Ryan himself as wounded, misunderstood innocent:

When I mention one of his most rabid critics in the commentariat, the liberal New York magazine writer Jonathan Chait, he begins to chuckle. “That guy hates me,” he says. “I don’t even know what he looks like. Never laid eyes on the guy. But he does not like me.” …

Ryan is fighting a well-drawn caricature of himself as a wolf in bro’s clothing — a right-wing radical who disguises his agenda to dismantle the social safety net with an earnest Homecoming King of Congress act …

“I’m so used to that,” Ryan says of the personal attacks. “It’s just—” he pauses to think for a moment. “The key is you get thick skin, but not impermeable skin so that it changes who you are.”

The underlying problem here is a massive gulf between Ryan’s rhetoric and his policy agenda. Ryan’s famous budget consists primarily of extremely deep cuts to programs benefiting low-income Americans. What’s more, Ryan’s policy commitments preclude any deviation — his belief in higher defense spending, absolutely no new revenue, no cuts to Medicare or Social Security for current or near-retirees, and balanced budgets within a decade arithmetically require staggeringly large cuts to income support for the most vulnerable.

How to resolve this tension? One way is to assert that the best way to help poor people is to cut their subsidies. Ryan does indeed make this case, and Coppins endorses it:

If [Ryan’s] rhetoric lacks poetry, his arguments against the current state-centric approach to aiding the poor is compelling. Since Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “war on poverty,” the U.S. government has spent an estimated $13 trillion on federal programs that have resulted, 50 years later, in the highest deep poverty rate on record.

This statistic is one of the very few fact-based policy assertions in Coppins’s story. It is wildly misleading. Ryan is using a measure of poverty that excludes a lot of the subsidies government gives to the poor. He’s saying, in other words, that giving poor people money doesn’t make them less poor, if we disregard the money government gives them. If we count such subsidies, then the War on Poverty has in fact reduced deep poverty substantially:

Government policies have significantly reduced the share of the population in poverty, and the share in deep poverty, throughout the 45-year period we examine, and with especially pronounced effects during economic downturns, in particular, during the recent Great Recession. Overall, we find that in the absence of government benefits, the poverty rate would have risen from 25 percent to 31 percent from 1967 to 2012, instead of falling from 19 percent to 16 percent. So in 2012, government programs reduced poverty by 15 percentage points — nearly half of its pre-transfer level — up from a reduction of 6 percentage points — about a quarter of its pre-transfer level — in 1967.

Ryan also wants to escape responsibility for the draconian consequences of his proposals. “I can’t speak for everybody and put my stuff in their budget,” he tells Coppins. “My work on poverty is a separate thing.” Their budget? The great vision statement for which Ryan has been widely hailed is now somebody else’s?

Of course, the entire problem is that poverty programs are part of the budget. If you want to include more of something, you need less of something else. Reconciling competing priorities is the entire point of a budget. Nobody should be allowed to say they’re for all the wonderful, popular stuff in the budget, plus all this other stuff that isn’t in the budget, but also without increasing the deficit at all, let alone people who also happen to be the chairman of the budget committee.

There’s not much else to argue with in Coppins’s account, which relies on visual description to press his case for Ryan’s good faith. For those of us who have not been exposed to Ryan’s in-person seductive charms, it may be notable that he is altering the basis for his public appeal in a significant way. Ryan burst upon the national scene by presenting himself as a wonk’s wonk, the concerned, helpful man with the calculator here to help America avoid its fiscal crisis. Ryan the Wonk did not always know what he was talking about, but the important thing is that he looked like he did.

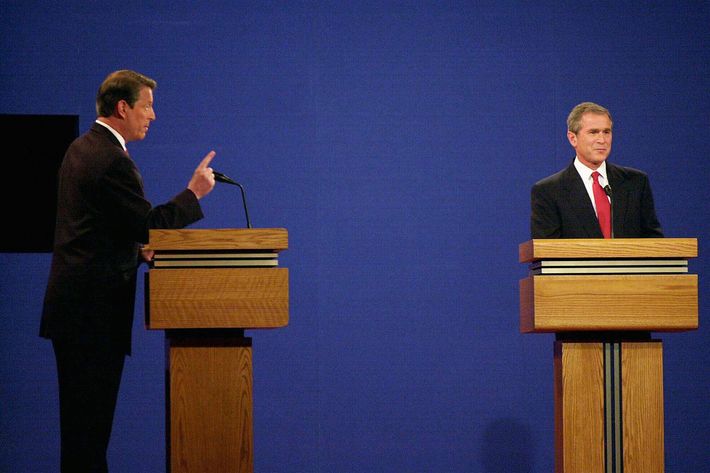

The newer iteration wants to make his case in non-pecuniary terms. Point out that his budget enacts a massive upward redistribution of income, and he will tell you about his soul. It is very much the same method used by George W. Bush to ward off criticisms of his fiscal priorities. (When Al Gore stated during a 2000 presidential debate that Bush had taken funding from children’s health insurance in order to cut taxes for oil companies, Bush replied, “If he’s trying to allege that I’m a hard-hearted person and I don’t care about children, he’s absolutely wrong.”) It’s a tactic that meets both Ryan’s needs and the needs of journalists possessed of great confidence in their ability to judge the sincerity of political theater.