Presidential speeches and budgets are symbolic measures, especially when the Congress is controlled by an opposing party disinclined to pass anything the president wants. But over the last few weeks, Obama has used the symbolic power of these tools to leave an imprint on American politics, if not on government itself. Obama has cemented a decision by the Democratic Party to make quality universal child care the next major goal of American liberalism.

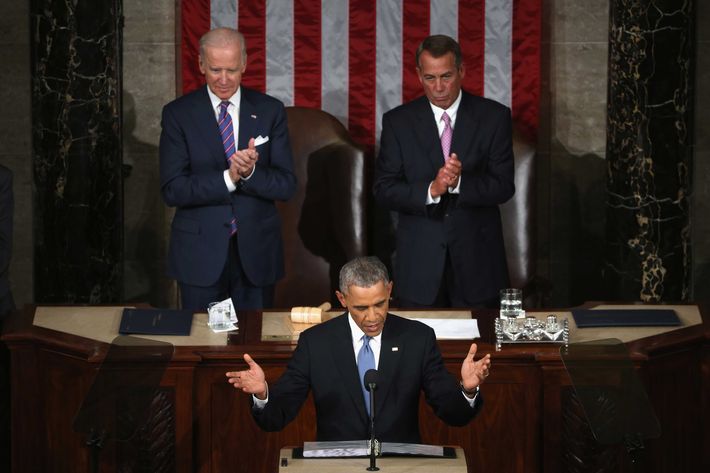

Obama signaled his intention in the State of the Union address, when he announced, “it’s time we stop treating child care as a side issue, or as a women’s issue, and treat it like the national economic priority that it is for all of us.” His budget, released this week, includes $200 billion over the next decade to support child care and early education. But this is not Obama’s idea. He is merely ratifying a consensus that has formed among liberal-policy intellectuals.

The rise of early education brings together two powerful strands of liberal thought. The first can be thought of as a kind of social policy: Our society is still constructed as if most households still consist of a working father and a stay-at-home mother, even though that old model has mostly disappeared. The costs of caring for children too young to attend public school is overwhelming for working-class and even middle-class parents. Because many parents can hardly afford decent child care on their incomes, huge swaths of the system are horrifying and even dangerous nightmares, as Jonathan Cohn documented two years ago. Parents are forced to stash their children in understaffed and frequently unsafe facilities.

Conceived of this way, America’s child-care problem is a humanitarian disaster. It requires public subsidy because most parents cannot adequately finance their own child-care needs, just as Social Security came into existence because most Americans could not adequately provide for their own retirement. If society expects parents to work, it ought to make it possible to do so while raising children, which is a thing we want and need to happen. And this moral-justice logic is a strong enough rationale on its own.

Congress passed a universal child-care law in 1971, but President Nixon, tamping down a revolt among conservatives outraged at his peace overtures with communist China, issued a surprising veto. Nixon’s rationale captured the culture-war implications that surrounded the issue at the time. “For the Federal Government to plunge headlong financially into supporting child development,” he wrote, “would commit the vast moral authority of the National Government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing over against [sic] the family-centered approach.” At the time, when women accounted for a mere 38 percent of the workforce, the notion of public endorsement and subsidy for a program that would allow mothers to avoid their socially required duty to care for their own children seemed, to a major segment of America, radical and threatening. In the current day, when women account for nearly half the workforce, condemning child care as a threat to the family has a more antiquated ring. In the place of a distrust of working mothers, though, the Republican Party has developed a dogmatic opposition to new spending programs that would have shocked even Nixon. (Who even tried to pass universal health care, only for his proposal to be killed by Democrats who deemed it too moderate.)

The other main difference between today and 40 years ago is that advocates of universal child care now see it not just as a social issue but an economic strategy.

A large and growing body of research suggests that early education exerts a disproportionate impact on the development of the brain. From this perspective, warehousing millions of tiny future workers in facilities that hardly bother to stimulate them, or leaving them to stare at the television or sit in a playpen stashed in their mother’s workplace, is a horrendous human-capital strategy. American day care is the economic equivalent of having rutted dirt roads for interstate highways.

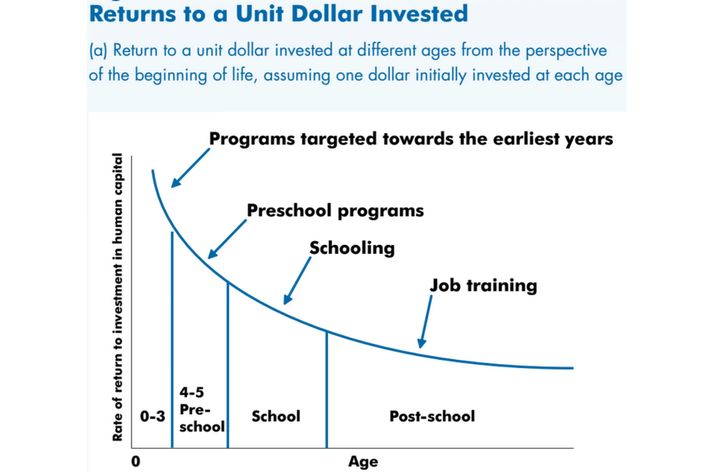

University of Chicago economist James Heckman has conducted probably the most influential work in the field. Heckman has argued that the social return on investments in early childhood education can run at an annual rate of at least 14 percent a year. These programs do not merely benefit hard-pressed parents, or even their children, but society as a whole. Children who enjoyed well-designed early childhood education are less likely to need special education, commit fewer crimes (and are thus less likely to consume expensive criminal-justice-system resources), and earn more money over their lifetimes, which means they pay more taxes.

Conservative critics have disputed these findings, citing long-term studies measuring the impact of Head Start, a long-standing child-care program with uneven results. But Head Start has yielded inconsistent results because it mostly provides inexpensive babysitting, rather than high-quality education. The most exciting findings in the field suggest well-designed education for pre-kindergarten can have a transformative impact.

Heckman’s findings build on the still-nascent field of brain research, the conclusions of which have overturned long-settled assumptions. A person’s mental capacity, far from being fixed by nature, is deeply impressionable to its environment beginning at a very young age. American schooling traditionally begins at kindergarten, treating schooling in the years beforehand as mere babysitting. But these formative years, when the brain develops its eventual potential, may be more, not less, important. We have invested most heavily in the years with the least impact, and ignored the years with the most.

Bill Clinton’s presidency invested enormous hopes in worker retraining, which the 42nd president imagined would retool the industrial workforce for the mental rigors of the new economy. Yet job training never realized the potential its advocates imagined. Early childhood education has replaced worker retraining as liberalism’s human-capital strategy.

When the next Clinton candidacy takes shape, some version of the idea Obama has embraced is likely to hold a place of prominence. Economist Heather Boushey, who has studied the connection between child care and economic opportunity for more than a decade, is the executive director at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a think tank started by John Podesta, who is now a senior Hillary Clinton advisor. These are the sorts of transmission channels that turn ideas into platforms.

In addition to its emerging status as party doctrine, early childhood education solves several of Hillary Clinton’s messaging problems at once. Affordable child care as a social issue appeals to the working poor all the way through to the upper middle class. It lends policy heft to her status as potentially the first female president in American history. And it would undergird a forward-looking economic program, simultaneously attacking the problem of stagnant opportunity for working parents and their children.

It took 65 years from the time Harry Truman proposed universal health care for Obama to sign a law actualizing his vision. Universal child care may not happen in the next presidential administration, which will begin with the same implacable Republican Congress that makes Obama’s proposal dead on arrival. But it will eventually happen, and probably in less time.

*This article appears in the February 9, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.