The conservative line on the Obama administration’s nuclear deal with Iran is that President Obama has been taken to the cleaners, either out of naïveté, or perhaps because he secretly hopes for Iran to obtain the bomb. It is possible that Obama has negotiated an unnecessarily weak deal. It is likely (as I’ll elaborate at the end) that the Iran deal will be a bad one. It is even possible that it’s unnecessarily bad (though this is, or should be, very hard for any of us without access to confidential negotiations to believe with any confidence).

But the conservative case against the Iran deal is hard to take seriously because the right has made the same case against every major negotiation with an American adversary since World War II. If there is such a thing as a deal with an enemy state strong enough to satisfy conservatives, no American president, Democratic or Republican, has ever been shrewd or tough enough to strike it.

Opposition to the Yalta agreement, in which Western leaders submitted to the fait accompli of Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, was a foundation of modern conservative foreign policy. The Yalta agreement may not have been the Roosevelt administration’s strongest possible bargain, but the only real alternative would have entailed continuing the war against the Soviets after defeating Germany. Dark insinuations about the treaty’s traitorous intentions formed the basis for Joe McCarthy’s paranoid ravings. In the 1950s, conservatives rallied the “Bricker Amendment,” a scheme to amend the Constitution to limit the president’s ability to strike foreign treaties like Yalta. It failed mainly because of the opposition of President Eisenhower, with whom conservatives maintained a generally hostile relationship.

In the 1960s, the United States worked with the Soviets to sign the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, a pact to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to states that had not yet obtained them. National Review denounced it as “immoral, foolish, and probably most impractical, a policy that makes nonsense of our defensive alliance in Europe, that favors our enemies and slights our allies.” Ironically, the NPT is now the legal basis for the international effort to prevent Iran from obtaining nukes. So the nuclear agreement conservatives originally denounced as folly is now the very thing they demand be upheld.

The right also fiercely opposed Richard Nixon’s opening to China. Conservative columnists called the administration’s recognition of the communist regime “the liquidation of the anti-Communist stance of the American Government” and compared it to (of course) Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler. They likewise denounced Nixon’s policy of detente with the Soviet Union as “one of the greater triumphs of the Soviet propaganda machine,” and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) as “profoundly unwise.”

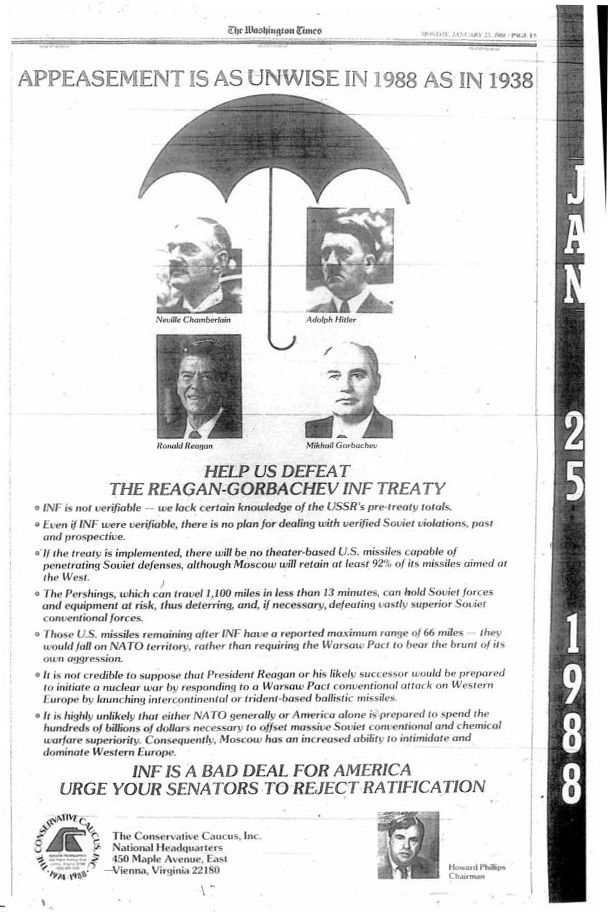

Ronald Reagan ran for president as a staunch opponent of the SALT treaty, but abided by its provisions anyway. He went on to sign the intermediate-range nuclear forces treaty, to massive right-wing dismay. Conservatives believed he had been “beguiled by Gorbachev, to the detriment of American interests,” reported the New York Times. The right mobilized against the treaty, comparing Reagan’s diplomacy to you-know-who:

And, of course, when the Obama administration sought to extend the Start treaty with Russia, conservatives went predictably ballistic.

Conservative opposition to Obama’s expected deal with Iran is based on a critique of Obama’s peculiar failings. He is naive in the face of evil, desperate for agreement, more willing to help his enemies than his friends. The problem is that conservatives have made this same diagnosis of every American president for 70 years. They do not merely oppose this deal, they oppose all of them, because they believe evil regimes cannot be negotiated with. Their analysis of the Iran negotiations is not an analysis at all, but an impulse.

None of this is to say that the Obama administration has handled Iran the correct way. Even if it has, the agreement is unsatisfactory for the same basic reasons that every treaty with a brutal regime is unsatisfactory. The truth neither Obama nor his critics will acknowledge is that there probably isn’t any potential deal that can prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons. On the other hand, bombing Iran is also unlikely to work, as is maintaining effective international sanctions for years on end. The least bad option will probably be, in the end, having to rely on deterrence to stop Iran.

To negotiate with dictators is to concede their legitimacy at some level — to give up (or at least postpone) the aspiration that they will democratize. It is also to accept a geopolitical landscape of grim power-sharing. There are better and worse ways to cope with limits on power. But the conservative response to Obama’s negotiations is the expression of a pathological inability to grapple with the limits of military power at all.

*A version of this article appears in the April 20, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.