Public officials, activists, and planners all agree: New York needs a new Penn Station to replace the reeking rodent warren commuters have to scrabble through now. Finally, it’s going to happen! Vaults will soar! Daylight will set the concourse aglow! Best of all, an assortment of government agencies will kick in more than $300 million. The year is 1993.

Five years later, President Bill Clinton puts the finishing touches on the delayed deal: “Today, that vision has become a reality,” he announces. New York senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan burbles: “This is an epochal moment, a turning point.” They are both lying.

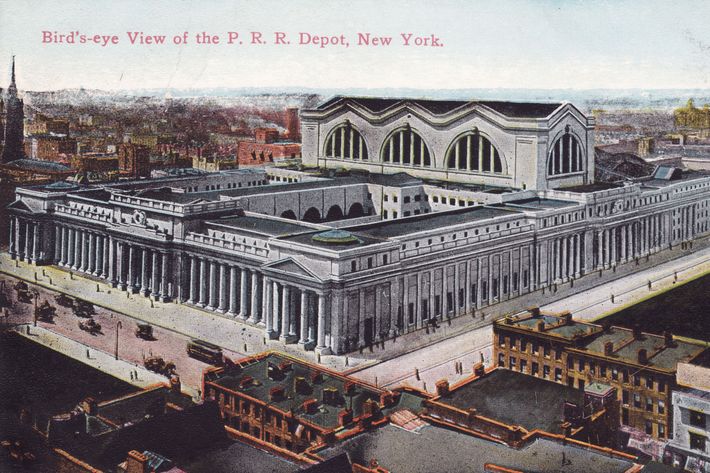

The original Penn Station lasted 53 years; the effort to replace the replacement has eaten up nearly half as long again, and counting. Every so often politicians proclaim, budgets are drawn up, and designs are unveiled. Then nothing happens. So Governor Andrew Cuomo’s familiar announcement this week that Penn Station’s pit of despair would soon be magicked into majesty seems like an invitation to scoff. So does anything make this latest eruption of optimism rise above all the others?

Actually, yes.

For one thing, Penn Station is just one widget in Cuomo’s imperial-scale vision for the state’s basic machinery. He revived the construction of a new Tappan Zee Bridge and, last summer, launched an overhaul for La Guardia Airport. Weeks later, he applied a defibrillator to Gateway, a wildly expensive, indispensable, and moribund project to build a pair of train tunnels beneath the Hudson River: The prognosis is still uncertain, and even if digging started tomorrow, it would still be a race against time to complete them before the existing tunnels crumble. But Cuomo is finally feeling, and communicating, the urgency. And two days after making his Penn Station pitch, Cuomo resurrected another dormant megaproject, a $1 billion expansion of the Javits Center. Fortunately for New Yorkers who like to get places and do things, Cuomo has hitched his reputation — and, perhaps, a future presidential campaign — on his ability to deliver these perpetually deferred goodies. Ambition is the lubricant of infrastructure.

Maybe Cuomo is just hedging his bets, figuring that if one of these projects doesn’t get completed but others do, his pharaonic legacy won’t suffer too much. And yet he also seems to understand that the pieces are interconnected. Gateway would pump more New Jersey commuters into Penn Station, making it even more urgent to overhaul the festering inferno we have now. If the city gets in on the action, a rebuilt junction could galvanize a well-planned neighborhood, stretching from Seventh Avenue to a bigger Javits.

We’ll get a hint of that possible future soon, when new Amtrak platforms and entrances through the Farley Post Office building across Eighth Avenue open next year — the first bit of the long-planned Moynihan Station. Cuomo’s isn’t really a plan, more a plan to have a plan, and it takes various possible shapes, one of which involves demolishing the Paramount Theater in Madison Square Garden. Ideally, the rest of the Garden would move, too, so that it’s no longer a concrete hulk smothering passengers below. The Municipal Art Society has been pushing a move to the Morgan Post Office building between Ninth and Tenth avenues and between 28th and 30th streets. Once that location would have felt like the middle of nowhere. A few years from now, it will be a block from the tall, dense complex of office towers and apartment buildings at Hudson Yards.

But the real reason that this time a new Penn Station might happen is that Cuomo doesn’t want to pay for it. In his shopping cart of items with multi-billion-dollar price tags, the government piece of a new Penn Station almost looks like petty cash. The amount of public money that Cuomo is dangling — $325 million, divided among the Port Authority, the federal transportation department, and Amtrak — is only slightly more than Moynihan scared up a generation ago, only now it represents barely a tenth of the total cost. The rest of the $3 billion project will pour in from as-yet-undetermined private developers.

In a perfect world, this would be terrible news. Instead of a public-works project, this is now a real-estate deal to build a shopping mall with train access. (Cuomo’s presentation wrapped the proposal in generic renderings of a shopping concourse in a glass box, which, the critic Alexandra Lange suggested on Twitter, would amount to building an Apple Store with an Apple Store inside.) But it’s no good getting wistful about tax dollars at work: Remember that the original, lamented Penn Station was one company’s baby, at a time when virtually all public transit was a form of capitalist enterprise.

The reality is that if the private sector has more money than the government does, Cuomo is wise to tap it, fast. He has an aptitude for knocking heads together, and while real-estate developers don’t react like State Assembly members, his real clout is the ability to make a deal. There’s urgency now — not just the prospect that a tunnel will fail, but also that the market will swerve and the cash dry up, or that a neighborhood in transition will fill with towers, making it even more difficult and expensive to do what must be done. The last thing we want is for Cuomo’s proposal to join the long litany of coulda-shoulda-wouldas.