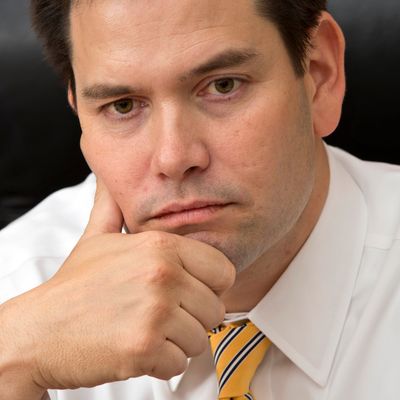

Marco Rubio built his presidential campaign upon a strategy that has succeeded many times in the past, and (if betting markets are correct) stands a strong chance of succeeding again. He is running a campaign that is more or less optimized for the general election rather than the primary — a tactic that holds him back from viscerally channeling conservative anger, but which, by maximizing his electability, makes his nomination more attractive to party elites. But because Rubio has found himself principally challenged by Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, who are running campaigns based purely on gratifying Republican base instincts, his strategy has magnified the contrast to the point where Rubio’s principal ideological identifier is now “moderate.” The term has been employed everywhere — by Rubio’s rivals, by his friends, and by neutral reporters. There is no sense in which that description is true — not in relation to modern Republican politics, and perhaps not even in relation to his allegedly more extreme opponents.

Rubio burst onto the national scene in 2010 as a self-described “movement conservative” who managed to draw backing from important Establishment Republicans, like the Bush family, and tea party groups. On foreign policy, he has embraced full-scale neoconservatism, winning enthusiastic plaudits from figures in the right-wing intelligentsia, like William Kristol. While much of the Republican Party has recoiled from the excesses of the Bush administration’s wild-eyed response to the 9/11 attacks, Rubio has not. He was one of 32 senators to oppose the USA Freedom Act, which restrained the federal government’s ability to conduct surveillance. He was one of just 21 senators opposing a prohibition on torture, insisting, “I do not support telegraphing to the enemy what interrogation techniques we will or won’t use.” Indeed, Rubio now delights his audiences by promising to torture suspected terrorists, who will “get a one-way ticket to Guantánamo, where we’re going to find out everything they know.”

On social issues, Rubio has endorsed a complete ban on abortions, even in cases of rape and incest (a stance locating Rubio to the right of George W. Bush). He has promised to reverse executive orders protecting LGBT citizens from discrimination and to appoint justices who would reverse same-sex marriage. The centerpiece of Rubio’s domestic policy is a massive tax cut — more than three times the size of the Bush tax cut, and nearly half of which would go to the highest-earning 5 percent of taxpayers. By reducing federal revenue by more than a quarter, Rubio’s plan would dominate all facets of his domestic program, which is otherwise a mix of conventional Republican proposals to eliminate Obamacare, jack up defense spending, and protect retirement benefits for everybody 55 and up. Rubio has voted for the Paul Ryan budget (“by and large, it’s exactly the direction we should be headed”). He has proposed to deregulate the financial system, thrilling Wall Street. (Richard Bove, author of Guardians of Prosperity: Why America Needs Big Banks, wrote a grateful op-ed headlined, “Thank you, Marco Rubio.”)

What, then, accounts for Rubio’s moderate image? One reason is the issues Rubio has chosen to emphasize. His conventionally conservative domestic policies would, if enacted, bring about an epochal shift in the role of government and the distribution of wealth in the American economy. (And given his party’s entrenched majorities in Congress, Rubio would be able to enact those policies.) But Rubio has not emphasized these ideas publicly. He has given far more attention to his plan to increase college affordability. As Rubio has said, “You’ll hear me spend a tremendous amount of time talking about higher-education reform.” This formulation perhaps gives away more than Rubio intends. Rubio’s higher-education reform plan, while largely innocuous, is also minuscule in scale — a third-tier throwaway line in a State of the Union speech. Its importance is trivial in comparison to his radical domestic-policy commitments. Rubio spends a tremendous amount of time talking about it because doing so allows him to position his platform as new and different from those of a generic Republican without any of the risk of actual heterodoxy.

A second reason is Rubio’s ill-fated 2013 attempt to shepherd bipartisan immigration reform through Congress. Because of the prominence of his role in that episode, which consumed a large share of his brief tenure in national politics, Rubio’s support for reform has disproportionately colored his public image. But his history provides no reason to believe the issue sits close to Rubio’s heart. As a Senate candidate in 2010, Rubio forcefully opposed any path to citizenship as “amnesty.” In the wake of the 2012 election, after the Republican Party wrote a post-mortem calling for the passage of immigration reform and efforts to reach out to young people and minorities, Rubio loyally reversed his position and led the pro-reform charge, and initially he drew support from important figures in the party. But when restrictionists revolted against the bill, Rubio abandoned his own proposal and has promised never to support comprehensive reform again. The fairest conclusion to draw from his two reversals is that Rubio does not hold especially strong beliefs on the issue at all, taking whichever position seems to be the most effective means of advancing traditional Republican policies (for which he has displayed consistent support). Republican donors naturally adore Rubio.

While Rubio’s willingness to sponsor immigration reform tells us very little about his convictions, though, it reveals a great deal about his political strategy. Rubio is a political pragmatist. And pragmatism is the fundamental divide inside the GOP. While split on foreign policy between neo-conservatism and neo-isolationism, Republicans have near-unanimity on economic and social policy. A domestic Rubio presidency would look very much like a Cruz presidency or a Bush or a Walker presidency. Any Republican would sign the bills passed by Paul Ryan’s House and Mitch McConnell’s Senate.

What Republicans disagree about is how to handle a situation where the president does not sign those bills. Cruz’s response to whip up conservative suspicions that the Republican failure to enact its agenda over President Obama’s objections represents a secret betrayal. Trump’s response is to break the stalemate through unique force of personality. Both of them signal their solidarity with the base through demonstrations of anger and cultural resentment. But, while making themselves attractive to their base, Trump and Cruz harden a cultural polarization that seems to leave their party at a disadvantage in the general election. He avoids statements that make him appear ostentatiously deranged, like Cruz visually comparing Obama to a Nazi, or Trump … doing just about everything Trump has done. The third cause of Rubio’s moderate image is that he declines to indulge right-wing paranoia on such topics as whether Obama is a Marxist, or the looming threat of Sharia law in the United States, trading the opportunity to indicate solidarity with the base for general election viability. He husbands his potential electoral weakness for matters of policy, not symbolism.

Rubio’s value to the party is that he approaches its predicament realistically. He will reach out to Democratic-leaning constituencies with personal appeal without compromising on core agenda items Republicans care about. Everything Rubio says — his message of generational change, a “new American century,” his frequent invocations of his parents — ties into his youth and heritage as the son of immigrants. If Democrats attack his policies, he will change the subject to his biography. “If I’m our nominee, how is Hillary Clinton gonna lecture me about living paycheck to paycheck?” he boasted at a Republican debate. “I was raised paycheck to paycheck.” Rubio is the embodiment of the Republican donor class’s conviction that it needs to alter nothing more than its face.