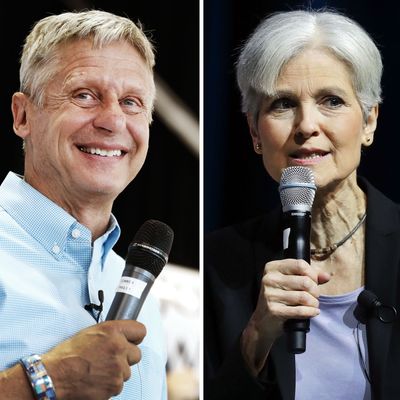

One of the obvious variables affecting the outcome of the 2016 presidential contest is the fate of two minor-party nominees who are likely to be on the ballot in a majority, if not all, states: Libertarian Gary Johnson and Green Jill Stein. In the RealClearPolitics average of national polls offering a four-way race, Johnson is currently at 8.9 percent and Stein is at 3.4 percent. If the Clinton-Trump contest tightens, the 12.3 percent of the vote currently going to candidates who are not going to win could provide one of the keys to the ultimate outcome.

There are three very different assumptions observers tend to make about Johnson and Stein voters. The first is that minor-party presidential candidates tend to fade down the stretch. The second is that this may not happen in 2016 because Clinton and Trump are both so profoundly unpopular. And the third is that Johnson voters (being right-of-center) will go to Trump when push comes to shove while Stein voters (being left-of-center) will wind up in Clinton’s column, making Trump the net beneficiary of any trend away from the minor-party candidates.

Polling maven Mark Blumenthal takes a look at Survey Monkey’s very large sample for its internet tracking poll and tests all of these assumptions.

One bit of external evidence he mentions regarding the autumn destiny of the minor-party candidates is the coincidence that both Johnson and Stein ran four years ago. It’s been forgotten that they did a whole lot better in some preliminary polls than in the actual returns.

Polls that included Johnson and Stein in September 2012, for example, estimated their combined vote totals at levels varying between 4 and 7 percent; actual support for those candidates barely exceeded a single percentage point when all the votes were counted. Polls conducted in the summers of 2008, 2004 and 2000 that included third party choices exhibited very similar patterns, finding support that reached the high single digits yet melted away to just a percentage point or two on Election Day.

Could 2016 be different because of the widespread disdain for Clinton and Trump? Probably not, according to Blumenthal, because supporters of the two major-party candidates are far more likely to feel certain of their preferences than are supporters of Johnson and Stein. Clinton and Trump supporters are also significantly more likely to vote, which is not surprising given the indicators (especially youth and lack of partisanship) that Johnson or Stein supporters are marginal voters.

As for the idea that Trump will benefit more from a fade in minor-party support, that’s true, but only marginally. Blumenthal finds that Johnson supporters split pretty much evenly when “pushed” to make a choice between Clinton and Trump, while Stein’s supporters go almost entirely into Clinton’s camp. That’s consistent with the phenomenon of Clinton doing slightly better in two-way as opposed to four-way match-ups in the polls. Unless the two-party race is a dead heat, this probably won’t be a game-changer.

One other Blumenthal finding that is peripheral to the main question does jump off the page: Virtually all the unpredictability in the presidential race appears to be among the “true independent” voters most likely to show a preference for Johnson or Stein. Breaking the electorate down by partisan self-identification, Blumenthal finds virtually no “defections” among major-party voters. For all the talk of Republican elected officials privately and sometimes publicly dissing Trump, Clinton is only pulling 5 percent of self-identified Republicans. And for all the talk of former Sanders supporters considering a Trump vote, the mogul’s only attracting 3 percent of self-identified Democrats. This polarization, moreover, extends fully into the universe of independent leaners: Clinton’s leading Trump among independents who lean Democratic 73-2, while Trump’s leading among indies who lean Republican 76-3. If you accept Blumenthal’s evidence that the true indies most likely to vote for Johnson and Stein also divide pretty evenly in a two-party race, then you can understand why “base mobilization” is such a priority for the Clinton and Trump campaigns. Superior turnout could matter most in a close race.

Funny things could still happen, of course. You could have some major-party meltdown that spikes third- and fourth-party support late in the game. If it were to happen almost immediately, it could push Gary Johnson over the threshold for making the debates, and if he lays off the doobies before ascending the stage, that could be something of a game-changer for him. It is famously a strange political year. But odds are the minor parties will have a minor effect on the outcome.