In 2015, Grover Norquist, who has successfully defined unconditional opposition to taxes as the defining tenet of party orthodoxy, waxed enthusiastic about one state in particular that was leading the way for the nation. “Kansas is the future,” he told an interviewer. “Kansas is the model.” Kansas was the state where Sam Brownback, the former congressman who mentored a young staffer named Paul Ryan, implemented supply-side tax cuts that, Brownback promised, would usher in prosperity and fiscal stability.

Now Brownback’s tax cuts have failed so dramatically and incontrovertibly that the state’s Republican legislature overrode Brownback’s veto to eliminate them. Incredibly, a majority of the Republicans in both chambers of the state legislature voted against the tax cuts. In a new interview with Russell Berman, Norquist insists the failure in Kansas does not tell us much at all about anything. “If you’re a Republican looking for a model,” he says, “Kansas is not the model.”

One might think that the economists who designed this now-repudiated plan would have been cast out of the party, or at least embarrassed into rethinking their assumptions. Yet nothing of the sort has taken place. Stephen Moore and Art Laffer, the supply-siders who crafted the failed Kansas experiment, are also taking the lead in designing Donald Trump’s tax plan. Their op-ed urging the president to throw himself behind massively regressive, debt-financed tax cuts found its way into his hands. So profoundly did their argument impress Trump that he instructed his advisers to immediately release a tax-cut plan mirroring the recommendations made by the architects of the Kansas debacle. Now the machinery of government is in the hands of people determined to replicate a policy so unmistakably erroneous that the majority of their own party could no longer live with it.

The pattern on display in Kansas has recurred over and over in Republican politics for more than a quarter century. (In this sense the state is, like Norquist said in 2015 but now denies, a model.) The pattern has four steps:

1. Demand a program of regressive, debt-financed tax cutting.

2. Deny or minimize the first-order effects of these tax cuts (reducing revenue available to the government, and increasing the incomes of rich people) and instead emphasize second-order effects: the tax cuts will trigger faster growth, and perhaps inspire legislators to reduce spending. Both these speculative effects will, the tax cutters assure the skeptics, prevent the predicted deficits from materializing.

3. Deficits in fact materialize when the predicted second-order effects fail.

4. Insist the tax cuts only failed because weak-minded legislators did not do their part to cut spending as required. Continue advocating regressive, debt-financed tax cuts.

Kansas fits the pattern perfectly. When Brownback passed his plan in 2012, enthusiasts dismissed fiscal skeptics. (Wall Street Journal editorial page, 2012: “The tax cut will force state politicians to restrain spending.”) When massive deficits appeared, the same cheerleaders blamed spending policies. (Wall Street Journal editorial page, 2015: “The real story is how unchecked spending, especially entitlements, can undermine tax reform.”) But weren’t the tax cuts supposed to prevent “unchecked spending”? Wasn’t this the very reason their supporters gave to discount the predictions that the tax cuts would create deficits?

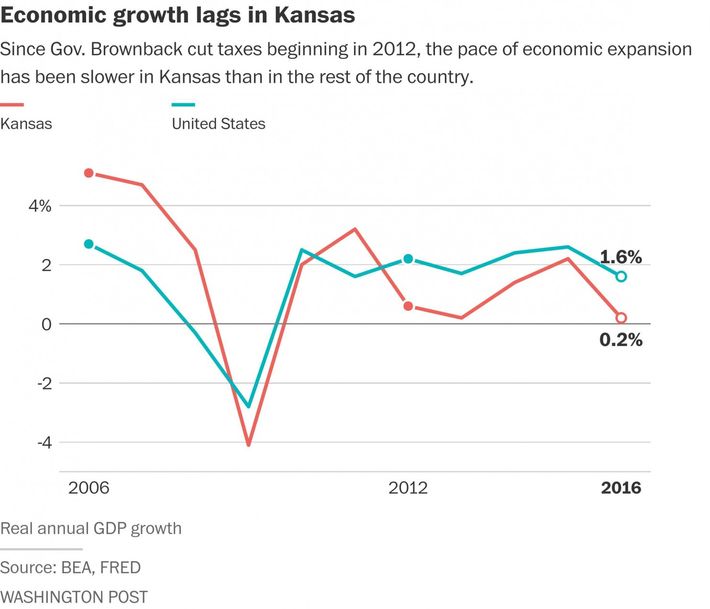

The tax cuts, which were sold above all as a plan to yield faster economic growth, produced nothing of the sort. The state, which had been growing slightly faster than the overall U.S. economy before the tax cuts, grew more slowly afterward:

Of course, the most famous example of the model is George W. Bush’s tax cuts. Conservatives overflowed with confidence that the Bush tax cuts would produce an era of prosperity, and that predictions of fiscal irresponsibility were doomsday nonsense. Norquist called Bush “Reagan’s son,” and insisted the tax cuts would drive down spending: ”The goal is reducing the size and scope of government by draining its lifeblood,” he said in 2003. When none of these things happened, the culprit was, of course, excessive spending. The Bush White House “didn’t focus on spending,” Norquist said in 2008. “They didn’t make it a priority. And this predates September 11. It just wasn’t on the list of things they were going to do.” Like Trotsky being erased from old Soviet photographs, now the hero of the supply-side revolution was revealed to have been a traitor from the very outset.

What enables Republicans to persist in this charade is that duping themselves is not completely necessary. Many, perhaps most, conservative elites believe as a matter of principle that taxing the rich at higher rates is morally wrong. They consider the first-order effects of regressive tax cuts — the transfer of resources from the public fisc to “the makers” — desirable. Since most Americans do not approve of tax cuts for the rich, this requires them to focus on the alleged second-order effects. And it explains why they continue to support the policy even when those second-order effects continuously prove ephemeral.

The entire identity of Republican politics has followed this same four-step pattern. The GOP made the Bush tax cuts of 2001 and 2003 the centerpiece of its domestic policy platform. When the economic and fiscal goals of the tax cuts failed, and a cycle of miserable job growth culminated in a massive speculative collapse, the party rebranded itself as a new, austere rebooted version of the old thing. The failures of the Bush-era party turned out to be its deviation from conservatism. It had been corrupted and seduced by big spending. And now the Trump-era party is right back to where it was under Bush, following the same policies and insisting the result will be different.