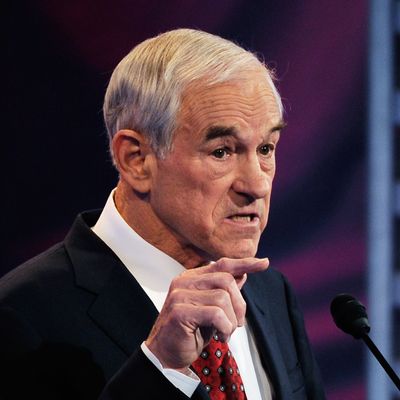

The furor over the racist newsletters published by Ron Paul in the nineties is, in some ways, more revealing than the newsletters themselves. In a series of responses by Paul and his supporters ranging from anguished essays to angry dismissals to crazed conspiracy diagrams (check out page seven), the basic shape of the Paul response has emerged. Paul argues that he was completely unaware that, for many years, the newsletter purporting to express his worldview consistently expressed vicious racism.

This is wildly implausible, but let’s grant the premise, because it sets up the more interesting argument. Paul’s admirers have tried to paint the racist newsletters as largely separate from his broader worldview, an ungainly appendage that could be easily removed without substantially altering the rest. Tim Carney argues:

Paul’s indiscretions – such as abiding 9/11 conspiracy theorists and allowing racist material in a newsletter published under his name – will be blown up to paint a scary caricature. His belief in state’s rights and property rights will be distorted into support for Jim Crow and racism.

The stronger version of this argument, advanced by Paul himself, is that racism is not irrelevant to his ideology, but that his ideology absolves him of racism. “Libertarians are incapable of being racist,” he has said, “because racism is a collectivist idea, you see people in groups.” Most libertarians may not take the argument quite as far as Paul does — many probably acknowledge that it is possible for a libertarian to hold racist views — but it does help explain their belief that racism simply has no relation to the rest of Paul’s beliefs. They genuinely see racism as a belief system that expresses itself only in the form of coercive government power. In Paul’s world, state-enforced discrimination is the only kind of discrimination. A libertarian by definition opposes discrimination because libertarians oppose the state. He cannot imagine social power exerting itself through any other form.

You can see this premise at work in Paul’s statements about civil rights. In a 2004 statement condemning the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Paul laid out his doctrinaire libertarian opposition. “[T]he forced integration dictated by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 increased racial tensions while diminishing individual liberty,” he wrote. “The federal government has no legitimate authority to infringe on the rights of private property owners to use their property as they please and to form (or not form) contracts with terms mutually agreeable to all parties.”

Paul views every individual as completely autonomous, and he is incapable of imagining any force other than government power that could infringe upon their actual liberty. White people won’t hire you? Then go form a contract with somebody else. Government intervention can only make things worse.

The same holds true of Paul’s view of sexual harassment. In his 1987 book, he wrote that women who suffer sexual harassment should simply go work somewhere else: “Employee rights are said to be valid when employers pressure employees into sexual activity. Why don’t they quit once the so-called harassment starts?” This reaction also colored his son Rand Paul’s response to sexual harassment allegations against Herman Cain, which was to rally around Cain and grouse that he can’t even tell jokes around women anymore.

This is an analysis that makes sense only within the airtight confines of libertarian doctrine. It dissipates with even the slightest whiff of exposure to external reality. The entire premise rests upon ignoring the social power that dominant social groups are able to wield outside of the channels of the state. Yet in the absence of government protection, white males, acting solely through their exercise of freedom of contract and association, have historically proven quite capable of erecting what any sane observer would recognize as actual impediments to the freedom of minorities and women.

The most fevered opponents of civil rights in the fifties and sixties — and, for that matter, the most fervent defenders of slavery a century before — also usually made their case in in process terms rather than racist ones. They stood for the rights of the individual, or the rights of the states, against the federal Goliath. I am sure Paul’s motives derive from ideological fervor rather than a conscious desire to oppress minorities. But the relationship between the abstract principles of his worldview and the ugly racism with which it has so frequently been expressed is hardly coincidental.