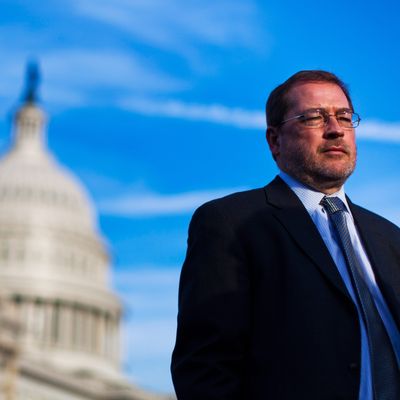

One of the more inscrutable steps we in Washington must go through on our way to some kind of budget agreement is the ceremonial sacrifice of Grover Norquist. The head of Americans for Tax Reform, Norquist has come to occupy a wildly disproportionate place in the national conversation, mainly through his role as keeper of the GOP’s anti-tax pledge — or, as Norquist and many Republicans call it, the Pledge. The Pledge, which no Republican at the national level has violated for more than two decades, forbids its signers from voting to increase tax revenue in any form (except as the ethereal byproduct of growth via lower taxes).

Over the weekend, several Republicans on Sunday morning talk shows distanced themselves from and even mocked Norquist. Today, National Review editor Rich Lowry and The Wall Street Journal editorial page rise to Norquist’s defense. Norquist is a key figure in the conservative movement, chairing regular weekly meetings at which conservative congressional staffers, lobbyists, activists, and opinion journalists from organizations like National Review and The Wall Street Journal editorial page coordinate a party line. The Pledge itself is merely a ratification of the Republican Party’s decision to organize itself around the principle of opposing taxes above all else. Norquist’s allies are rallying to his defense mainly as an expression of tribal solidarity among conservative movement allies.

The problem for all of them is that the Pledge has become a completely ineffective tool to enforce the party’s anti-tax dogma. The expiration of the Bush tax cuts within a few weeks means that taxes will rise automatically. Forbidding Republicans from cutting a deal won’t stop that from happening. Indeed, once that happens, Republicans could strike a deal to cut taxes from the new, higher level without breaking their Pledge. And since Republicans will have less leverage once the Bush tax cuts expire, the Pledge actually harms the anti-tax cause, by preventing the party from negotiating the best possible deal on taxes.

Norquist’s response to this unfortunate circumstance is to simply wish it away. When asked about a potential deal, in which Republians would agree to set tax rates above current levels but below Clinton-era levels in return for spending cuts, Norquist insists that such a deal is a “unicorn.” No such deal exists or can exist, he maintains, and therefore there is no need to confront the Pledge’s unworkability.

But the rest of the party is attempting to extricate itself from the Pledge as a matter of practicality even as they hew to its general aims. The columns by Lowry and the Journal editorial page all gently concede that the Pledge does not actually help them in these particularly circumstances, while gamely defending Norquist anyway. The same basic principle is at work in comments like these, from Senator Pat Toomey:

I don’t intend to violate any pledge. My pledge is not to support higher taxes. What we’re faced with in just a few weeks is a massive tax increase. If I can help ensure that we don’t have that tax increase, then I believe I’ve fulfilled my pledge to fight for the lowest possible taxes.

Nobody is more committed to the anti-tax cause than Toomey, who once ran the Club for Growth, which is a similar organization to Americans for Tax Reform except possibly even more fanatical. Toomey, unlike Norquist, isn’t professionally committed to upholding the sacred role of the Pledge as a holy document transmitting the eternal word of Reagan to his followers for ever and ever.

The Norquist Kabuki ritual going on in Washington is the Republican Party attempting to figure out a strategy to deal with Obama’s budget leverage — and, in particular, a way to hold together the party line in the face of circumstances where just killing any deal won’t work.