You remember the scene in Game Change, when John McCain’s adviser tells him that selecting Sarah Palin is “high risk, reward”? And McCain (or Ed Harris as McCain, or whatever) starts grinning uncontrollably? That is the approach the entire Republican Party has taken in almost every situation it has found itself since 2008. Republicans greeted Barack Obama’s presidency with a calculated wave of total opposition. They would not cut a deal on health care or on the federal budget, each time accepting the risk of total defeat rather than settling for half-measures, like giving Democrats some kind of token health care reform or small tax increase.

The gamble was that by denying Obama any support, they would render his presidency wholly partisan at best, and a dysfunctional failure at worst. They would increase their own chances of denying him a second term, and that their return to power would allow them to claim a full and absolute break with the past. They shoved all their chips onto tonight’s election. When the networks called it at 11:15 p.m., the totality of the right’s failure was clear. And because they bid up the stakes as high as they could, their loss was unusually devastating.

The gamble was not totally crazy, I have argued, because 2012 may have been the last chance to enact an undiluted conservative agenda. The electorate is driving steadily leftward, with the oldest voters representing the GOP’s strongest constituency, and the youngest voters its weakest. Every four years, a new 18–22-year-old cohort arrives that is more liberal than the one that has died off in the interim. The Republicans face a double peril with the youth vote. A far lower proportion of young voters are white, and those who are white are far less likely than their parents or grandparents to vote Republican. White voters over the age of 65 selected Romney by a twenty-point margin. White voters under 30 split evenly.

The financial crisis opened a window of opportunity for Republicans. Obama would be presiding over the worst economic calamity in eight decades, and nothing he did to mitigate the crisis would change the fact that his term would be marked by mass suffering and disillusionment.

At the outset of summer, GQ’s Reid Cherlin spoke with Mitt Romney’s high command, which was overflowing with glee at its coming triumph — “not merely a 51–49 win but a run-the-table walloping that will send Obama into the history books as an undisputed calamity for America.” Hubristic as it sounds now, among conservatives it was no more optimistic a sentiment than predicting a sunrise. They had spent nearly the entirety of Obama’s presidency confidently predicting his demise. Obama was “crashing before our eyes,” his administration “entering its pitiful phase,” Americans turning against him in a “harbinger of doom.” In an eerie replay of the Carter administration, the right’s favorite historical comparison for Obama, the economy was dragging him down and, to make matters worse, he was “a very bad politician.” Romney designed his entire campaign as if this assessment was self-evident.

Obama’s imminent (or ongoing) collapse was to be the seminal event that shook loose his terrifying ascendant coalition. Rather than attempt to pry away his constituencies on the issues that drew them to Obama, Romney and Ryan harped on young voters’ disillusionment. Obama had failed to secure comprehensive immigration reform. Young people faced bleak employment prospects. The party’s undisguised goal was to discourage the new voters who flocked to Obama in 2008 from voting at all, leaving the electorate older and, hence, whiter than it had been and probably ever would be again, at least in a presidential election. Those white voters would vote their pocketbooks, which is to say, overwhelmingly against Obama. And then henceforth Obama, like Carter, would be the symbol of failure and big government overreach, a political bogeyman for future Democratic candidates.

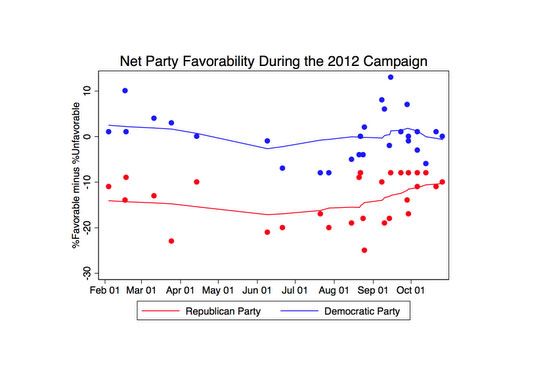

The great gamble failed. It failed for many reasons: The economy recovered just enough in 2012, Mitt Romney ran a mediocre campaign, Obama ran a strong one. Among the most important is a factor conservatives seem to have never reckoned with — their party has never recovered the public’s trust:

Fed up though voters may be with bitter partisanship in Washington, and angry though they may be with the painfully slow recovery, they were never eager to hand the keys back to the Republicans. Conservatives would not make the ideological sacrifices needed to reposition the party in the center. They gambled that discontent with Obama alone would be sufficient to propel them back to power.

The policy consequences of that failed gamble are immense: Universal health insurance will go into effect, and when the Bush tax cuts expire on January 1, 2013, Obama will be able to restore a plausible stream of tax revenue without needing the ascent of the unbowed Republican House.

The political repercussions may be just as enormous. While any number of future events could intervene — Obama could lose his second term to a scandal, or a foreign policy crisis — he looks very well poised to consolidate and expand the electoral revolution that helped sweep him into office. The economic recovery appears to be gaining momentum — perhaps not quite soon enough to allow him to have run a Morning in America reelection campaign, but advanced enough for him to preside over a second term that feels like true prosperity. If Obama presides over a strong and continuous recovery, his approval will rise and his policies will be vindicated. He could cement the partisan and ideological leanings of his rising coalition.

Democrats will not keep winning forever. (In particular, their heavy reliance on young and non-white voters, who vote more sporadically, will subject the party to regular drubbings in midterm elections, when only the hardiest voters turn out.) Eventually, the Republican Party will recast and reform itself, and the Democratic Party’s disparate constituencies will eat each other alive, as they tend to do when they lack the binding force of imminent peril. But conservatives have lost their best chance to strike down the Obama legacy and mold the government in the Paul Ryan image. “There is nothing more exhilarating,” Churchill once said, “than to be shot at without result.”