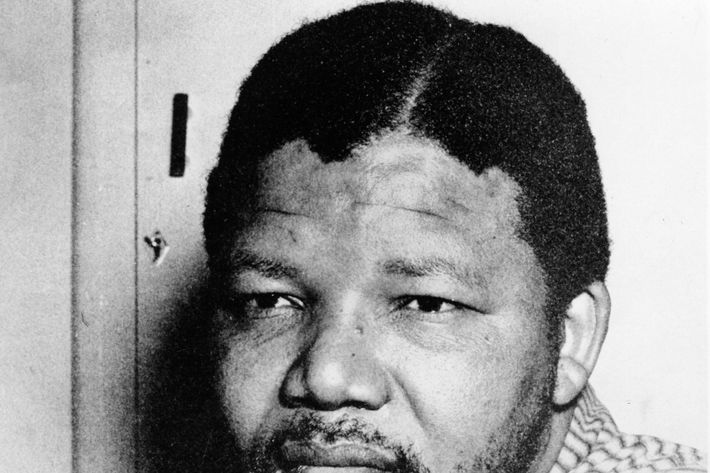

In 1985, William F. Buckley, founder and editor of National Review, wrote a column defending — or, to put it more accurately, expressing — his sympathy for the Apartheid government of South Africa. Buckley wandered through a series of points that would embarrass his successors today, most notably his opinion that Nelson Mandela belongs in jail. Most interesting, Buckley argued not only that the South African government served the strategic interests of American foreign policy, and that Mandela was a dangerous radical, but that South Africa should not dismantle Apartheid:

President Botha of South Africa is incontestably right in saying in effect that he was not elected leader of his government in order to preside over the liquidation of the South Africa he was elected to govern. Critics are perfectly free to contend that his election does not suit our political criteria. But having admitted that his government does not do so, it hardly makes sense to criticize him for proceeding on the basis of his (misbegotten) criteria. If you criticize somebody for being mean to his mother, don’t be surprised if he goes on to be mean to his mother.

Buckley’s logic here, while circular, is also completely airtight. You can’t blame a white South African president for continuing a policy of white supremacy. He was elected by whites! If the whites-only electorate wanted to dismantle white supremacy, it would have chosen somebody else. So there. Buckley does allow that the principle of white supremacy may be “misbegotten,” but later in the column he explains that it’s not entirely wrong, either. (“One-man one-vote is a fanatical abstraction of self government that not even the United States tolerates institutionally,” Buckley argues, citing the malapportionment of the Senate.)

Over the last century, the conservative line on racial questions has undergone a constant flux in its particulars. The distinguishing element of conservative thinking on race is the belief that, at any given moment, the balance of actual or threatened power is arrayed against whites. The conservative line often concedes that whites may have sinned against blacks in the past, and may even continue to do so, but that at the present moment the risk lies in taking things too far in the opposite direction.

These arguments are not always entirely wrong. They often contain important elements of truth: Mandela did have some dangerous communist allies; some affirmative-action programs can have terrible side effects; and so on. For that reason, whenever it’s plausible to do so, the specifics of conservative racial thinking need to be analyzed and debated on their merits, not stigmatized as racist. And even if conservative racial arguments had been completely wrong, it wouldn’t prove they would continue to be completely wrong forever. Still, understanding the history of conservative racial arguments is vital to understanding what conservative racial thinking is.

Quin Hillyer, in an alternately lucid, heartfelt, and feverish reply to a recent column of mine, expresses the timeless conservative belief that, whatever happened in the past, the racial scales have tipped. “The Left is so eager to see racism in every conservative heart and utterance that it ignores overwhelming evidence that more blacks these days feel racial animus toward whites, and more act in race-antagonistic ways, than do whites toward blacks,” he writes. “By huge margins, blacks vote in racial blocs more often than whites do.”

During the civil-rights era, many conservatives — like Buckley, the intellectual giant of his time — openly defended the principle of white supremacy. But as the civil-rights cause gained momentum, it became easier to simply object to the federal leviathan or to busybody northern activists and reporters. Variants of this thinking were possible even decades before the civil-rights movement. Ed Kilgore — citing Stephen Budiansky’s The Bloody Shirt, a history of the post–Civil War South I haven’t yet read — explains, “The subtext of Budiansky’s book is the extent to which white southerners convinced themselves and white people outside the South that they were the victims of Reconstruction, not the active and passive perpetrators of a strategy of organized terror designed to make the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution a dead letter.” As ridiculous as it may sound today to view the South of more than a century ago as a place where the cause of black equality had advanced too far, it really was true that Reconstruction was a large, intrusive program imposed from Washington.

Because conservative racial thinking has fared so badly, conservatives have had to periodically revise their canon, abandoning failed positions for more defensible ones. Conservatives have either abandoned or revised away their historical opposition to civil rights. But two decades after the end of Jim Crow, the struggle over South Africa gave them a second chance to get segregation right. Overwhelmingly, they failed it. But time and again, their response to historical error is to suture themselves off from history. Rick Santorum paid tribute to Mandela by presenting him as an ideological comrade in arms: “He was fighting against some great injustice, and I would make the argument that we have a great injustice going on right now in this country with an ever-increasing size of government that is taking over and controlling people’s lives — and Obamacare is front and center in that.”

At any given time, legitimate arguments can be arrayed behind the conservative position. Historical analysis doesn’t tell you everything you need to know about the merits of those arguments. In 1985, the Reagan administration argued that sanctions would lead to the immiseration of black South Africans and utterly fail to bring down Apartheid. George Will confidently echoed those arguments in a column dismissing divestment as “a moral Hula Hoop, fun for a while.” If true, that argument would have been persuasive. It wasn’t, though it doesn’t obviate all conservative arguments about race.

I have previously urged liberals not to assume bigoted motives lurking behind every conservative argument that could plausibly spring from racial animus. A number of conservatives cited that as a rebuke to my most recent column, which cites Quin Hillyer’s ugly rant against President Obama — “haughty,” “chin out,” “unembarrassed,” “not a shred of humility” — as an example of cultural obtuseness on the right. But of course I explicitly did not impute bigoted motives to Hillyer. I merely held it up as a sign of lacking awareness of the cultural resonance of that meme.

I certainly was not arguing, as many conservatives suggested, that racism explains the right’s opposition to Obama. Conservatives would oppose any Democratic president. Historical awareness ought to inform the mode of that opposition. If the president was Chuck Schumer, conservatives would hate him as much as Obama. But if conservatives denounced President Schumer as a money grubber, it would suggest, at the very least, that they don’t understand the historical character of anti-Semitism. And a failure to grasp the historical character of racism is not merely a recurring problem for conservative racial thought, it is its defining quality.