This last weekend, I finally saw 12 Years a Slave. It was the most powerful movie I’ve ever seen in my life, an event so gripping and terrifying that, when I went to bed ten hours later — it was a morning matinee — I lay awake for five hours turning it over in my mind before I could fall asleep. I understand it not merely as the greatest film about slavery ever made, as it has been widely hailed, but a film more broadly about race. Its sublimated themes, as I understand them, identify the core social and political fissures that define the American racial divide to this day. To identify 12 Years a Slave as merely a story about slavery is to miss what makes race the furious and often pathological subtext of American politics in the Obama era.

While its depiction of physical torture has commanded the most attention, I found the psychological torture more disturbing. To make a person a slave requires making them complicit in their own subservience, through rituals of degradation, such as forcing them to clap their hands to mocking songs, dancing for their masters, or being stripped, or compared to animals. The one time Northup tries to escape, he wanders immediately onto a lynch party, which underscores the threat of violence lurking invisibly everywhere. (And the threat of the noose survived in the South a century past the threat of the lash.)

Notably, the most horrific torture depicted in 12 Years a Slave is set in motion when the protagonist, Solomon Northup, offers up to his master engineering knowledge he acquired as a free man, thereby showing up his enraged white overseer. It was precisely Northup’s calm, dignified competence in the scene that so enraged his oppressor. The social system embedded within slavery as depicted in the film is one that survived long past the Emancipation Proclamation – the one that resulted in the murder of Emmett Till a century after Northup published his autobiography. It’s a system in which the most unforgivable crime was for an African-American to presume himself an equal to — or, heaven forbid, better than — a white person.

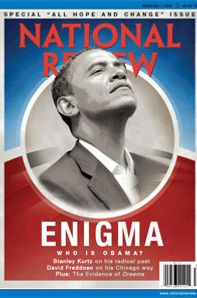

That context was fresh in my mind when I read this column in National Review by Quin Hillyer, a conservative pundit, think-tank fellow, and former candidate for the GOP nomination in Alabama’s first Congressional district. In the midst of an otherwise unremarkable rant against the perfidious big-government liberalism of President Obama, Hillyer unleashes this:

Every time decent people think the scandals and embarrassments circling Barack Obama will sink this presidency, we look up and see Obama still there — chin jutting out, countenance haughty, voice dripping with disdain for conservatives — utterly unembarrassed, utterly undeterred from any assertion of power he thinks he can get away with, tradition and propriety and the Constitution be damned. The man has no shame, no self-doubt, not a shred of humility, no sense that anybody else has legitimate reason to question him or hold any other point of view.

It is bizarre to ascribe haughtiness and a lack of a capacity for embarrassment to a president whose most recent notable public appearance was a profusely and even flamboyantly contrite press conference spent repeatedly confessing to “fumbles” and “mistakes.” Why would Hillyer believe such a factually bizarre thing?

One answer is that, by the evidence of this column, Hillyer believes all sorts of factually bizarre things. But most African-Americans, and many liberal whites, would read Hillyer’s rant as the cultural heir to Northup’s overseer: a southern white reactionary enraged that a calm, dignified, educated black man has failed to prostrate himself.

Before plunging further into a poisonously defensive racial debate, I should note that I feel certain Hillyer opposes slavery and legal segregation, and highly confident he abhors racial discrimination, and believes in his heart full economic and social equality for African-Americans would be a blessing. (More than two decades ago, Hillyer worked against the candidacy of David Duke.) His feeling of offense at Obama’s putative haughtiness (“chin jutting out”) might be a long-ago-imbibed white southern upbringing bubbling to the surface, but more likely a flailing partisan rage that could just as easily have been directed at a white Democrat.

You can accept the most benign account of his thought process – and I do – while still being struck by the simple fact that Hillyer finds nothing uncomfortable at all about wrapping himself in a racist trope. He is either unaware of the freighted connotation of calling a black man uppity, or he doesn’t care. In the absence of a racial slur or an explicitly bigoted attack, no racial alarm bells sound in his brain.

The broad social structure of white supremacy is not a part of the working conservative definition of racism. Conservatives see racism as a series of discrete acts of overt oppression. After slavery had disappeared, but before legal segregation had, conservatives considered it preposterous to claim that blacks suffered any systematic disadvantage in American life. (For an lengthy but fascinating expression of the conservative view, watch William F. Buckley in 1965 sneering his way through a debate over race relations with James Baldwin.)

Today, conservatives retroactively agree that legal segregation may have been unfair, but now things run on an even footing. Republicans, by a 60-40 margin, now believe discrimination against whites has grown to be a larger problem than discrimination against minorities. In fact, in nearly every way it can be measured, traditional white-on-black racism persists. Jamelle Bouie lists a few of them: Experiments show candidates with white-sounding names are vastly more likely to get callbacks than candidates with black-sounding names with equally impressive résumés; realtors show fewer homes to prospective nonwhite home buyers than to white buyers of equal financial standing; the criminal justice system imposes large racial disparities for the same criminal behavior; and on and on.

None of these experiments are known, or would even sound plausible, to avid followers of conservative news sources, where “racism” is encountered primarily as a politically motivated slander against conservatives by liberals. Again, it bears repeating that most conservatives find Klan-style white supremacy foreign, and usually completely unacceptable. The racial fissures of the Obama era do not look like 1957 Little Rock. Undisguised racism, while numerically frequent — it’s a big country — has largely remained confined to the political margins. Tea party activists have suppressed openly bigoted signs at their rallies, National Review fired two blatantly white-supremacist writers, a Republican precinct chair had to resign after boasting that a restrictive voting law would target “lazy blacks.”

Instead, the racial battlegrounds of the Obama era have settled on a series of more ambiguous controversies. Conservatives have made endless jokes based on the strange premise that Obama is unable to express coherent thoughts unless reading from a teleprompter, defined health-care reform as “reparations,” imagined a Reagan-era program to subsidize telephone use for the indigent is actually “Obamaphones,” or complained when black entertainers or athletes socialize with the First Family. The accusations of racism that follow merely confirm to conservatives that black-on-white racism is a canard, that the balance of oppression has turned against them.

Conservatives can transport themselves for two hours into the hellish antebellum world of 12 Years a Slave and experience the same horror and grief that liberals feel. What they cannot do, almost uniformly, is walk out of the theater and detect the still-extant residue of that world all around them.