The news that the insurance exchanges in Obamacare have exceeded their original enrollment projections — the projections made before the bungled website rollout cost two months’ of sign-up time and created a branding catastrophe for the entire program — is sending reverberations of shock through Washington. One immediate conclusion is that the Republican war to strangle Obamacare in the crib has come to pieces. The plan assumed, correctly, that the new law would be most vulnerable in its nascent stage. Republicans hoped that a combination of legislative attacks, on-the-ground activism, and coordinated messaging could deprive the new insurance exchanges of the customers they needed to form a critical mass, either as a political constituency or as an actuarially stable mix of customers. They failed.

Obamacare’s non-trainwreck also reveals something broader and deeper about American politics. The Obamacare wars pit two opposing camps who not only have different ideas about the role of government, but different kinds of ideas about the role of government.

One of my longstanding fixations, going back almost a decade now, is that we make a mistake when we think of liberalism and conservative as symmetric ways of thinking. On economic policy, at least, they are asymmetric. Liberals believe in activist government entirely as a means to various ends. Pollution controls are useful only insofar as they result in cleaner air; national health insurance is valuable only to the extent that it helps people obtain medical care. More spending and more regulation are not ends in and of themselves. Conservatives, on the other hand, believe in small government not only for practical reasons — this program will cost too much or fail to work — but for philosophical reasons as well.

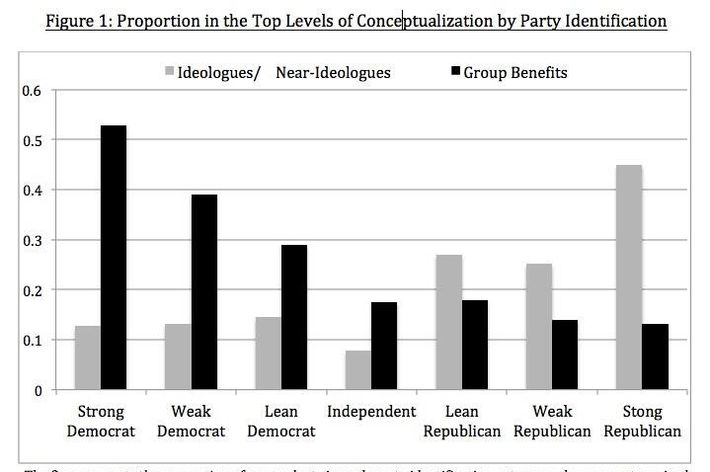

A new political science paper by Matt Grossman and David Hopkins bears out this way of thinking about American politics. The authors find a fundamental asymmetry between the Republican and Democratic coalitions. They examined survey results and other data among voters, activists, and elites, and found that Republicans express their beliefs about government as abstract ideology (big government is bad) while Democrats express their beliefs in the form of benefits for groups. The differences are enormous:

The different ways of conceptualizing the debate over government spills over into every other way in which the parties operate. Democrats are more favorable toward moderation and political compromise; Republicans toward ideological purity and principle. It’s not coincidental that Republicans have instigated more high-stakes partisan escalation in Congress.

The asymmetry has also colored our understanding of issues like Obamacare. I like analogies, so let me try a different one. Suppose a new barbecue restaurant opens up in town. Is it any good? On the one hand, you have traditional food critics. Imagine that you also have an equal-size group of meat-is-murder activists evaluating it. And whether or not you share their views on the ethics of meat, which you’re entitled to do, it stands apart from the question of whether people who do eat meat will like it. The traditional food critics may or may not like the place. They will tell you if the chicken is too dry. If the owner bungles the paperwork and can’t serve any food on opening night, they will probably be caustic. On the other hand, they’ll also tell you if it’s good.

The meat-is-murder activists, on the other hand, will predictably rip it to shreds. And, since the potential customer base for the restaurant does not include committed vegetarians, they will emphasize other reasons to shun the new animal death factory. The food is awful and overpriced. If the opening is delayed, maybe it will never open at all! Oh, it’s open now? The owner is probably cooking the books!

Conservatives have expressed from the beginning a theological certainty that Obamacare will fail. “Just as economic shortages were endemic to Soviet central planning, the coming Obamacare train wreck is endemic to big-government liberalism,” wrote Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol last August.

Of course, the website failure that ensued in October lent the complaints a ring of legitimacy. Some of the complaints were true. Liberal policy wonks were offering mixed, sometimes brutal, assessments of Obamacare. Conservatives predicted the law’s complete collapse. In January, I participated in a debate whose premise reflected the basic center of the public debate over health-care reform. The question before us was not “Is Obamacare worth its costs?” but “Is Obamacare beyond rescue?” A casual follower of the news would come away with the impression that Obamacare was probably doomed, after all.

It was not, of course. To be sure, the critics are clinging desperately to scraps of hope. Some of the customers haven’t paid their first premium yet! (True, but most of them have no reason to pay before their first bill is due.) Most of the sign-ups were already insured! (No, that’s a measure that includes off-exchange sign-ups, which include lots of rollovers from the pre-Obamacare market. States that ask have found 80 to 90 percent of new exchange customers were previously uninsured.) The new doom-saying has radically scaled back the scope of the promised disaster to come, and pushed it further off into the future. “I think they’re cooking the books on this,” sputtered Senator John Barrasso (R-WY) on Fox News. “Once all this is said and done, what kind of insurance will those people actually have? … How much more is it going to cost them?”

But at its root the idea of Obamacare’s collapse was tinged heavily all along with right-wing wish fulfillment. It’s not the case that the flaws were all imagined, and some aspects of the law will struggle badly. But the basic enterprise is workable. I used to go on Twitter and ask conservatives to lay out what the criteria for Obamacare working as intended would look like. I never got a satisfactory response. You don’t take your barbecue reviews from people who think meat is murder.