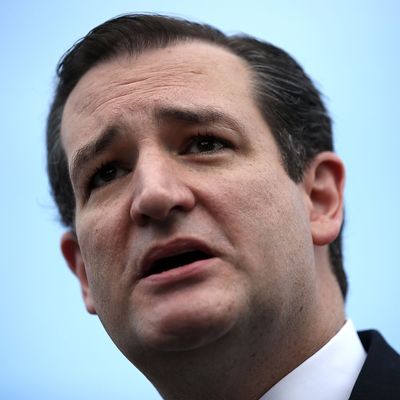

In the summer of 2013, with the Affordable Care Act about to begin enrolling its first customers in the new health-care exchanges, Ted Cruz warned Republicans that they were facing one final chance to kill the law. Once Americans had grown accustomed to the sweet comfort of affordable health insurance, Cruz foresaw, they would never give it up: “[Obama’s] strategy is to get as many Americans as possible hooked on the subsidies, addicted to the sugar. If we get to Jan. 1, this thing is here forever.”

Cruz may have been completely misguided in his belief that this logic dictated that Republicans instigate a government shutdown, but on the political economy of Obamacare, he was completely right. Indications of Cruz’s prescience are popping up everywhere.

In Kentucky, Mitch McConnell — who had vowed publicly and privately to “repeal this monstrosity” — was asked whether he would repeal the insurance exchange in his own state, and replied with word salad (“I think that’s unconnected to my comments about the overall question here”). When asked about repealing his state’s Medicaid expansion, he replied, “I don’t know that it will be taken away from them.”

Unpopular Pennsylvania Republican Governor Tom Corbett recently agreed to accept Medicaid expansion. Four more Republican governors — in Tennessee, Utah, Indiana, and Wyoming — have taken steps toward following suit. In Washington, the river of attacks against Obamacare issuing from Republicans has slowed to a trickle. (The number of Congressional news releases attacking the law has fallen by 75 percent this summer from last.) The Weekly Standard’s Jeffrey Anderson is warning darkly of an “anti-repeal wing” within the party. “Root and branch repeal is starting to look more like twig and leaf,” concedes Reason’s Peter Suderman.

As the law shocked detractors last spring by exceeding its enrollment targets, the anti-Obamacare community fixated on a final hope: that consumers looking to enroll this fall for next year would encounter soaring premiums. Not only has the hoped-for premium shock failed to materialize, rates seem to be coming in actually lower than this year. In a market where annual large price hikes have occurred for decades, the result is almost unfathomably positive.

A more telling development may be a behind-the-scenes fight within the Republican Party over a simple message vote. This National Review editorial, which is an attempt to persuade Congressional Republicans to stiffen their anti-Obamacare spines, contains the only reporting I’ve seen about this episode. The subject of the fight is a prospective Republican bill to repeal something called “risk corridors,” which are a temporary program to balance out the actuarial risk insurance companies face. If an insurer turns out to enroll disproportionately healthy customers, the risk corridors force them to pay back some of their profit to the government; if their consumers turn out to be disproportionately sick, they get money back from the government. Risk corridors are based on a similar program created by George W. Bush’s Medicare expansion, which was uncontroversial then and now. Since it’s part of Obamacare, conservatives have attacked it as a sinister corporate plot. Last year, Republicans learned of its existence and started calling the program an “Obamacare bailout” and demanding its repeal.

Aside from the merits of the case against risk corridors, which are extremely weak, the fascinating thing is that Republicans in Congress are now encountering resistance to attacking the “Obamacare bailout” from their own party. “Some Republicans say that the insurance companies should not be penalized for the defects of the law,” comments the frustrated conservative magazine. “The balkers also raise the worry that Democrats would accuse them of trying to cause premiums to increase.”

All this is a way of saying that Republicans in Congress worry about passing bills that would harm consumers and companies that are participating in Obamacare. The repeal of risk corridors is, of course, just a “message bill” — President Obama obviously would not sign it — which makes the reluctance all the more telling. Vulnerable Republicans have calculated that the message no longer helps them. It mobilizes more potential victims against them than it mobilizes potential anti-Obamacare voters. National Review’s editorial concludes, “If Republicans aren’t willing to break with the insurers over this issue, then in what sense do they oppose Obamacare?”

The Republican crusade against Obamacare is not ending; rather, it is shrinking and mutating. The party base will demand a presidential nominee who promises to repeal the hated law, just as it did in 2012. But the next Republican candidate will be running in an environment where repealing the law would create millions and millions of now-identifiable victims. Since the start of the year, Obamacare has gone from a weakness Republicans were salivating at the chance to exploit to an issue they no longer want to talk about. Two years from now, matters could be worse still.