Tom Cotton is the state-of-the-art Republican candidate — a perfect, and possibly too-perfect, blend of biography and opportunity. Cotton studied at Harvard, came by his conservatism early and fervently, served in Iraq, won the favor of Washington party elites like Bill Kristol, and can win a Senate seat by running in a midterm election in the deep red state of Arkansas. The only thing that might trip up Cotton is his principles, which he is feverishly jettisoning.

Cotton currently serves in the House as a frequent member of the “hell no” caucus, which votes against nearly everything. The trouble is that one of those things was the farm bill, which is popular in Arkansas because it lavishes subsidies upon major state industries. Cotton’s opponent, Mark Pryor, has assailed him for this vote. Cotton has shot back with an ad claiming that this only happened because “President Obama hijacked the farm bill, turning it into a food stamp bill.”

Cotton’s claim, as a myriad of independent fact-checkers have pointed out, is completely false. More interesting than Cotton’s transparent attempts to evade this fact is the ideological synthesis Cotton has developed in the course of making himself acceptable to the Arkansas electorate.

In his untrue ad, Cotton argues that he voted as he did because “career politicians love attaching bad ideas to good ones.” The bad idea here, in Cotton’s telling, is food stamps. The good idea is farm subsidies. This premise is worth considering.

Farm subsidies were created during the New Deal, at the height of both a catastrophic fall in farm incomes (at a time when farmers comprised a far higher share of the economy) and Democratic faith in a centrally planned economy. The planning fad manifested itself in such disasters as the National Recovery Act, a quasi-fascistic price-fixing scheme that failed, was struck down by the Supreme Court, and fortunately abandoned as a policy model in favor of more effective, market-friendly remedies for the excesses of the free market.

Yet farm subsidies have lived on. Their survival has nothing to do with any public policy merits. There is no persuasive economic rationale for why the government should write checks to people who operate farms as opposed to textile mills or construction firms or any other business. (Yes, people need to eat, but the market is capable of supplying food, just as it is capable of supplying clothing and shelter.) Farmers are also more affluent than the average American. Since they are overwhelmingly white and conveniently spread throughout nearly every state, their claim to public subsidy has gained some popular legitimacy.

Faced with his controversial vote against the farm bill, Cotton has urgently fashioned himself as an agri-supremacist. He has urged the locals to ignore the judgment of fact-checking journalists who pronounce his ad false: “I don’t think liberal reporters who call themselves fact checkers spent much time growing up on a farm in Yell County growing up with Len Cotton, so I think I know a little bill more about farming than they do.” Cotton’s identity as a onetime farmboy, by this argument, lends him a superiority in any dispute over farm policy that overrides even the facts themselves. Cotton perhaps first developed this epistemological theory while studying philosophy at Harvard.

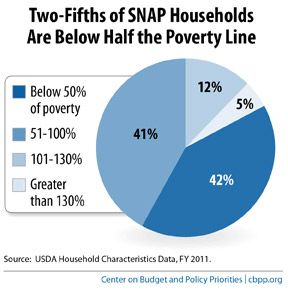

Cotton goes further still. Molly Ball, in an engrossing profile, reports that Cotton argues against food stamps because its recipients live high on the hog: “They have steak in their basket, and they have a brand-new iPhone, and they have a brand-new SUV.” As an argument against food stamps, this is laughably false: The program offers a benefit averaging $1.50 per person per meal, and its beneficiaries are quite poor:

What’s more, the charge Cotton falsely makes against the food-stamp program is in fact completely true about the crop-subsidy program. It furnishes its recipients with lavish benefits and many of of them are millionaires. But this is the program Cotton, even while fighting to the death against the one that feeds extremely poor, hungry people, vows to protect. Hell, he is even named after a major staple crop.

The snag in Cotton’s rapid path to national power turns out to be that his ideology is just a little too consistent. But he has found the solution. He is running not quite as a principled foe of government, but instead as a committed opponent of redistribution. Government is bad insofar as it gives money to the poor and vulnerable. Tom Cotton is going places in the Republican Party.