Mary Landrieu’s defeat last weekend marked a final, anticlimactic end to an epoch in American politics. After Landrieu’s defeat, Republicans now control every state legislature and governorship in the Deep South. The only states anywhere in the former Confederacy where Democrats hold a governorship or a Senate seat are Virginia and Florida — both of which, as Nate Cohn points out, have a majority of residents born outside those states. Democrats had pinned their hopes on a series of scions — Mark Pryor, Mary Landrieu, Michelle Nunn, Jason Carter — whose fathers had won in an era when Democrats carried those states, in the hopes of summoning their expired familial loyalties.

It is possible to view the decline of southern Democrats as a tragedy born of error. Kevin Baker, writing in the New York Times last month, lamented the Democrats’ loss of their ancestral heartland as the product of a misguided abandonment of economic populism. The real anomaly is that the Democrats managed to hold out in the Deep South so very, very long.

Barack Obama ran for presidency hoping to transcend old divisions, but his presidency has ironically lent renewed vigor to the most ancient division in American politics. The tea party, which presents itself as the heirs to the Founding Fathers, is actually an heir to one side of the American argument. One tradition bore intense suspicion of centralized government, venerated farmers and rural life, believed the Constitution forbade Congress from all but a handful of specifically enumerated fields of activity, felt comfortable with aggression and violence in both domestic life and foreign affairs, and defended existing social institutions against racial minorities and their allies. This political coalition has always had its strongest base in the Deep South. It is right-wing.

The other tradition advocated a stronger federal government (and deemed this expanded role Constitutional), considered public investment and education the best method of securing prosperity, was more averse to territorial conflict with neighbors, and was more solicitous of racial minorities. This coalition has always had its strongest base in New England. It is left-wing.

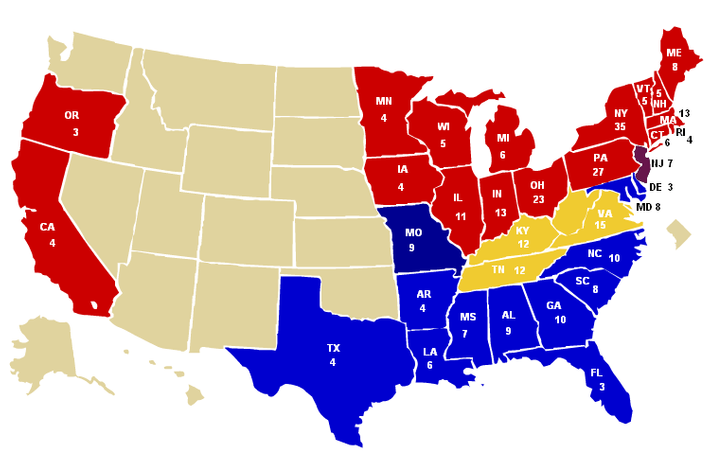

Throughout the 19th century, American politics were groping toward a system that reflected this ideological division. The birth of the Republican Party borrowed elements of these ideas from the dying Whigs and fused them into a coherent pro-government, socially liberal (by the standards of the day) party. The conservative Democrats held the South. The country’s divisions in 1860 looked almost identical to today’s, only with the party labels reversed:

It has taken 150 years for the reversal of the parties to work itself out completely. The Republican Party abandoned Reconstruction in 1876. Teddy Roosevelt led the progressive wing out of the Party in 1912. The progressive tradition grew among the northern wing of the Democratic Party, and figures like Woodrow Wilson and then Franklin Roosevelt eventually developed liberalism into a partisan creed. Yet they were still attached by deep social habit to the conservative southern wing.

By the middle of the 20th century, this new system was well entrenched. The strange thing about this period is that the liberal party — the one with the strongest commitment to expanding Washington’s role in the economy and advocating for racial minorities — had a base in the Deep South. Meanwhile, New England frequently supplied the Republican Party with its strongest support. During Franklin Roosevelt’s 1936 landslide, the only two states that voted Republican were Maine and Vermont. (Imagine a Democratic presidential candidate today losing Vermont — while winning 48 states.)

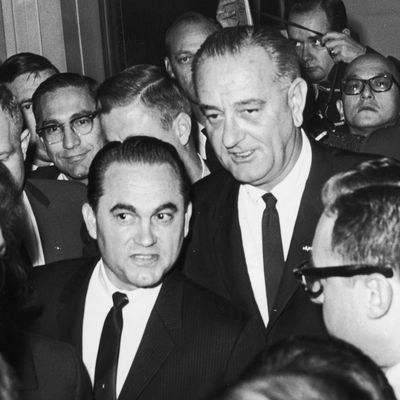

Many of the historians who came of age during this period saw it as natural that the liberal party would have its roots in the Deep South. Take Arthur Schlesinger Jr., the New Deal–era historian who went on to work for the Kennedy administration and who may have been the model 20th-century mainstream-liberal intellectual. His 1945 book The Age of Jackson cast the seventh president as a populist hero. Imagining Jackson as a kind of progressive made sense if you thought American history was moving toward a future in which the progressive party held sway in the Deep South. But we now know this was not the future. Gazing at Jackson with modern eyes reveals him as a perfect model for the modern reactionary, combining a Ron Paul–esque hatred of central banking, a Scalia-esque strict constructionism, a Sarah Palin–esque hatred for intellectuals, and a George W. Bush–esque love of military brio.

But Jackson today is still admired far more by Democrats (the heirs to his party) than by Republicans (the heirs to his creed). State-level Democrats continue to honor him. Obama’s first campaign for the presidency began to overtake Hillary Clinton when he staged a confrontation with her at … the 2007 Iowa Democratic Party’s annual Jefferson-Jackson dinner. If long-dead honoree Andrew Jackson, a virulent white supremacist even by the standards of his day, could have seen the uses to which his name would one day have been put, he’d have shot somebody.

If the mid-20th century forms your frame of reference, the Obama years represent a regrettable turn away from normality. But an even longer view of history leads to the conclusion that the trends of the Obama years have simply brought the two parties back into their natural resting position. The amazing thing about southern Democrats is not the scale of their fall, but the heights they were able to sustain in the face of all logic.

The rise of the tea party against Obama may be, in part, a neurotic reaction. But it also signals the appropriate, full resumption of the major argument of American history.