The Republican Party began the Obama era with a reflexive spasm of disgust against George W. Bush. The sins of the 43rd president, both real and imagined, propelled and helped to justify a wild lurch to the right. Was Bush a failed, unpopular president? This was only because he had sold out conservatism with his big-spending ways. Had Republicans turned against even policies they once supported — like TARP, fiscal stimulus, and cap and trade — in order to deny Obama any bipartisan cover? This was because those policies represented cardinal ideological error, of which the party had now cleansed itself.

The majority of the GOP now recognizes this lurch into anti-government purity was a mistake. The question is not whether the Republican party returns to Bushism, but whether its return is complete enough that this return can be led by George W. Bush’s actual brother.

The return to Bushism is the inevitable outcome of a partywide reevaluation that is already under way. Some Republicans, like Paul Ryan, see the Republican error against Obama as mostly a failure of messaging, and now want to sell the old conservative wine in new bottles. They are talking a lot more about inequality, and a lot less about “the takers,” but they continue to support the same policy goals. On the other hand, some intellectuals associated with the party believe its policy direction amounted to a substantive error, and want it to abandon, or at least soften, its relentless drive to redistribute income to the richest one percent of Americans and instead focus on middle-class families.

Among conservative policy intellectuals, a sharp debate has broken out. The traditional supply-siders argue that the party’s top goal ought to be the reduction of the top tax rate, while reformicons insist that it should instead focus on tax credits for middle-class families whose wages have stagnated. The resolution to this debate is very easy to forecast: The eventual Republican candidate will simply do both — cut taxes up and down the income ladder.

The only reason Republicans can’t come out openly for a big, debt-financed tax cut right now is that they have invested heavily in an anti-deficit message during the Obama presidency. But the pattern of Republican politics since the 1970s is to inveigh against deficits during Democratic administrations, and then expand those deficits by cutting taxes when their own party regains power. As the deficit falls, Republicans have already begun de-emphasizing the deficit in their message. By the time a prospective Republican president takes office, it will be a dead issue for them.

One can see the outlines of this compromise emerging in Jeb Bush’s domestic-policy speech in Detroit. Bush framed his agenda as a new, opportunity-focused program to appeal to new, underprivileged constituencies. He did not renounce any aspect of traditional Republican doctrine. Jonathan Martin asked Bush, after his speech, how his proposals would differ from the usual fare, and Bush’s answer, or lack thereof, was revealing. “In a brief interview after his speech, he did not say whether his policy prescriptions would be tailored to help the neediest Americans or would more resemble conservatives’ traditional solution of cutting taxes across the board,” reports Martin. “He did not directly answer when asked if cutting marginal income tax and capital gains rates would help those in need.” There’s no reason to believe Jeb Bush would oppose the Republican holy grail policy of cutting taxes for the rich. He will simply de-emphasize it in favor of more popular ideas.

This was, of course, the plan that George W. Bush ran on in 2000. Bush framed his tax cut proposal as aimed primarily at “waitress moms,” who he claimed, falsely, would receive the greatest share of its benefits. But George W. did cut taxes for the middle class, along with taxes for the rich. Jeb Bush’s nascent message resembles that of his brother in other ways, too. Both advocate centrist education reform proposals that have the potential to gain support from moderate Democrats. Both advocate immigration reform. And both wrap their candidacies in the symbolism of racial inclusion — George W. seemed to be photographed with African-Americans everywhere he went.

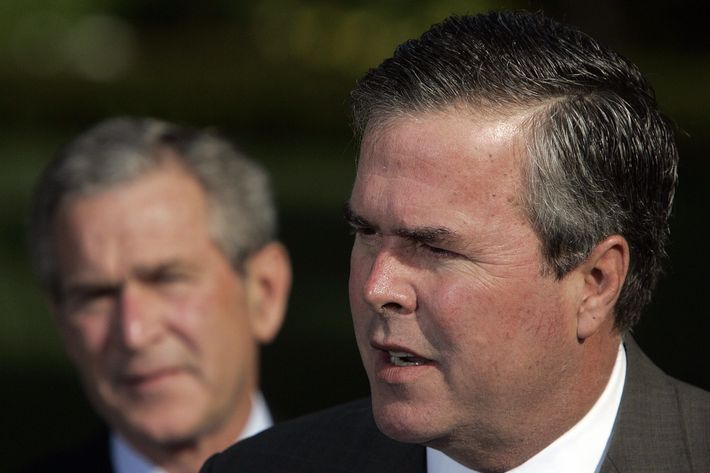

This is not to say a Jeb Bush presidency would inevitably recapitulate his brother’s. Jeb brings clear and distinct advantages. He is obviously smarter — not merely in comparison to his simpleton brother, but possibly even in comparison to the average politician. His marriage has given him a genuinely multicultural perspective that the two prior presidents Bush have lacked. And he has won election in a vital swing state.

Yet alongside these advantages there sits an enormous liability: the Bush name. George W. Bush is much less unpopular today than when he left office, thanks to the general nostalgic gloss that lifts the reputations of all ex-presidents over time. Nonetheless, he is not exactly a popular figure. Polls of Bush’s favorability rating show that about as many Americans approve as disapprove — a poor showing for a figure more than six years removed from the partisan conflict. Bill Clinton’s favorable ratings are far loftier, at a ratio of about two-to-one.

This is important, because swing voters tend to have little information about politics, and the connection with a former president is likely to play a large heuristic role in their decision. A person who does not follow politics closely, asked to choose between a Clinton and a Bush, is likely to remember that the economy prospered under the first and stagnated under the second. The Bush name, among Americans as a whole, remains poor branding.

Amusingly, the Republican donor class sees it in just the opposite terms. A New York Times report from last year, describing the early movement of donors to get behind a Jeb Bush 2016 campaign, matter-of-factly notes that its sources largely see the Bush name as magic: “The family name, he said, remains a powerful draw. “They love the Bush family,” Mr. Wynn said. “They love the whole package, and they feel Jeb is just a part of the package.”

The question is whether the rest of the party is ready to go along. After having loaded all their failures onto George W. Bush’s back, and cut him adrift to save conservative ideology from the taint of his undeniable failure, can the Republicans attach themselves once again to another Bush?